Rituals of Sacrifice

This essay was written at the invitation of the e-flux Notes editors in October 2022 but wasn’t published at the time.

***

I have nothing smart to say about the war. When it started, I got flooded with requests to write something. I was sleeping with my clothes on and spending hours a day in the basement with our neighbors. I refused to write anything.

I still don’t know the right words, and what’s presented as the right words feels superfluous. I don’t believe in the possibility of a moral high ground. I don’t believe that any war can be won. I only believe in fate and one’s alignment with it. All I can do to contain something that is bigger than myself is become a proper ritual vessel. Is writing something that may help me become one?

For a while, silence felt like the only appropriate way to honor the dead. But the proper mourning ritual entails its own completion. Then, one turns to remembrance.

***

The last item that had been shipped to me from overseas right before the war began was a heavy glass jar of YINA Recovery Body Treatment, an aromatic body butter infused with prehistoric Horsetail, or Equisetum, and Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis, also known as Buddha’s hand. In fact, at the time of writing this text, I was still using that same jar: when I was leaving Ukraine, it was one of the things I did fancy shoving into my single suitcase, while other items had to undergo severe revision so as not to make the said suitcase unliftable. I packed a pair of spoons, forks, knives, and teaspoons from my great-grandparents’ silverware. I packed all of my fanciest dresses and shoes—because basics like jeans and sneakers are heavy and also cheap enough to be bought upon arrival. The only paper book I brought with me was a bilingual German–French edition of Leibniz: Monadologie und andere metaphysische Schriften. It was lightweight and just the right size to store my train ticket in—but I haven’t finished reading it yet.

***

To tell you the truth, I wasn’t exactly fleeing the war itself—the hardest days had been over and my situation wasn’t as bad as some others had it. I was fleeing Ukraine. I had been trying to flee for several years before the war but something had not been letting me go, and then, all of a sudden, the freeze mode changed into the flight mode and I finally fled. I had been waiting to move to Shanghai, which I couldn’t do because of the pandemic, but I ended up moving to Berlin. I moved to Berlin because all of a sudden it was clear as day that it was where I had to be. I fled Ukraine because I started falling in love with a Russian in Berlin.

***

I spent the first five weeks of the war with my mother, in her hometown Nizhyn, an ancient town to the northeast of Kyiv. My father wasn’t there: he had got stuck at a forest base near Chernobyl with nine of his colleagues. They had diesel generators and some food so they managed to last there for more than a month. At some point, they had to hunt an elk. The Chernobyl area was under occupation but luckily the Russian troops didn’t know there were men in the woods who were staying in touch with the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Eventually, when there was no network in the area anymore, dad had to make 20-kilometer bike rides to get on the phone. Days when he couldn’t do that were paralyzing. Later this summer, he, an ecologist, received a medal for assisting the military.

Nizhyn wasn’t under occupation but for a long time, it was nearly encircled by the enemy troops and frequently shelled. There was combat going on right in the outskirts. Some 40 kilometers to the north people were drinking water from lakes and getting shot by the Russians while queuing up for bread. Nizhyn was comparatively safe but, to preserve that safety, no one was allowed to leave or enter the city. A couple of weeks in, the city started letting trucks from Kyiv and Cherkasy directions bring groceries to supermarkets. At some point, volunteer cars started bringing people out. At first, I wasn’t planning to leave before my father would be in safety. But then we all agreed that I had to do it: no one knew if there was going to be a chance to leave later on. I purchased a ticket for the Kyiv–Warsaw train. On some days the walls would be shaking worse than on other days. We were very lucky though.

The Russian troops had been re-dispatched just a couple of days before I was to leave. On their way to the East, they were firing chaotically at anything they happened to be passing by: a few houses in the vicinity got shelled and the city went into a 24-hour curfew. The next day, I checked with my driver and he was still up for the trip.

The curfew was lifted and we left at dawn. There were two women with kids in the van. The driver and two other men were sitting in the front. The trip would normally take just over an hour but this time it was five times longer: we had to pass twenty Ukrainian checkpoints. At each one, the men had to show their papers and in some cases to get out of the car. The military never cared for any of the women’s passports and barely glanced inside—mostly to smile and wish us a safe trip. The only time we left the car was to pee in the fields, a sublime experience. Being assured that my identity wasn’t of any importance—twenty times in a row—I fully agreed with it.

***

On the day the war began, my mother took the dried mugwort, Artemisia, that we had picked in the fields near the Black Sea the summer before, and placed it in all the corners of the apartment. A few days later, I used some of it for a foot bath. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, mugwort is used to warm the meridians, dispelling cold and regulating the flow of energy. I mixed it with sea salt to neutralize the overwhelming amounts of incoming information. Yes, we were extremely lucky to have running water and electricity. There were days when explosions would damage power lines but they’d always get fixed within 24 hours. There were days with no signal but it would come back.

I was working as a translator for the Washington Post and I had incoming assignments the whole time. Sometimes I’d be translating from the basement. When we got used to the sounds of air defense and shelling, I’d sit in the hallway and keep translating, with our cat packed in her carrier. Work kept me grounded and calm. But the pain was always there.

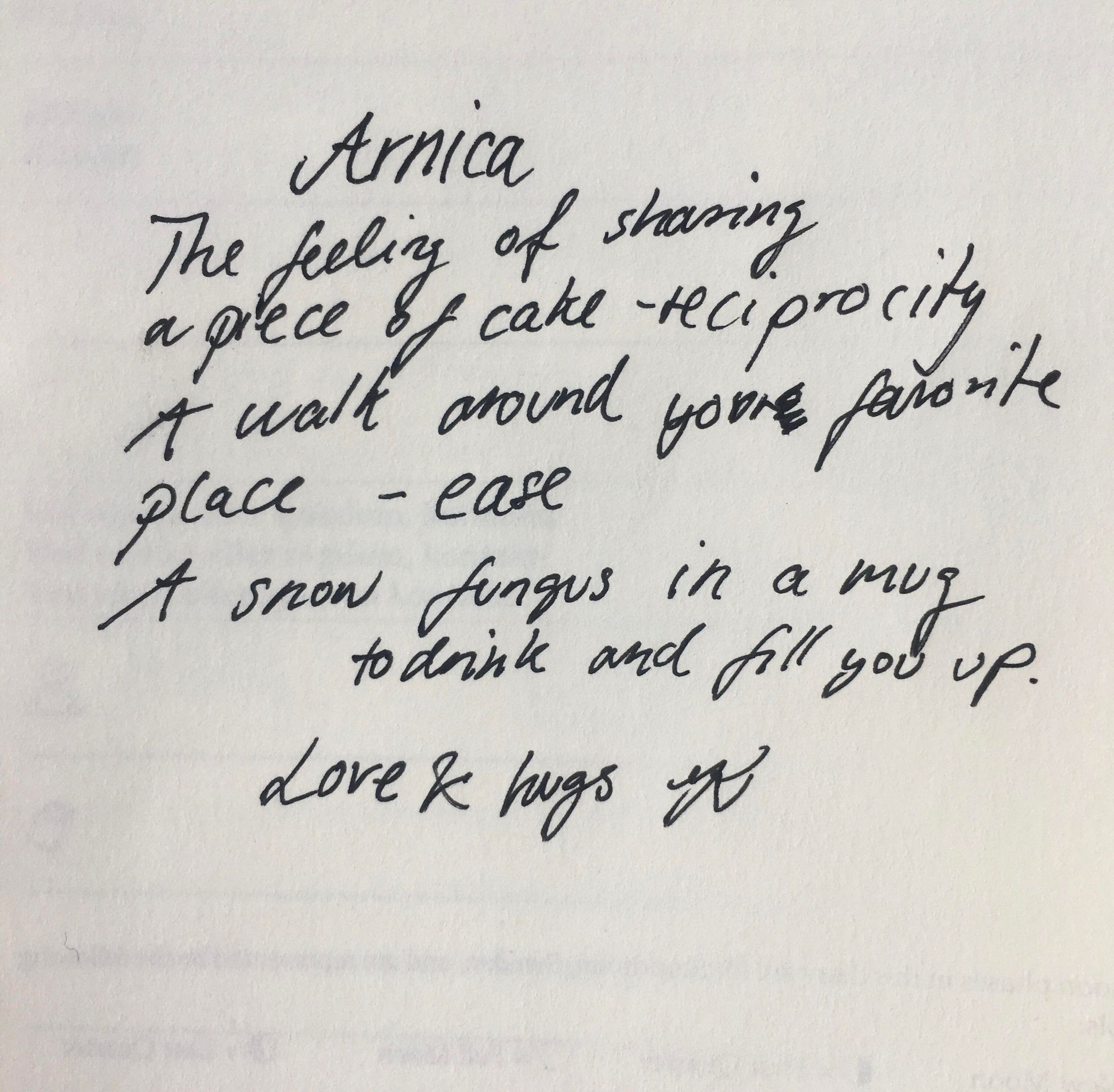

Two weeks into the war, my friend Karen Vestergaard Andersen sent me a message from Copenhagen that included the following prescription:

“If I’ve needed something badly but it was not available to me, my sister sometimes makes me write down the name of the needed remedy on a small piece of paper. Then one is to place this paper underneath a glass of water (not too cold preferably) and drink it. This is my hack of that practice because I cannot see why the body should not also respond to these sensations and things that in my mind are very real. This is my list for you 💛 You don’t have to believe in it for it to work—one of the smarter things my dad said to me.”

In fact, coincidentally, my mother had an Arnica hand cream, so I decided to start using it instead of my own, with Persian Rose. And every time I applied it, the entire recipe just worked. There was Arnica, and everything was a piece of cake, every place I walked around was my favorite, and every mug filled me up as if it had snow fungus in it. I was thinking about Tremella fuciformis, snow fungus, quite a lot, but there was no snow fungus to boil and drink. All I had was hydrolyzed snow fungus stored in two small bottles in the fridge: I was using the extract as an addition to facial masks. But I knew what to do with it: I poured it all out into the kitchen sink. This way, snow fungus extract would enter the sewage, its anti-inflammatory and nourishing effect reaching wherever water would flow.

See, I didn’t follow the provided instructions too closely but you certainly can. Sometimes you need a guideline and sometimes you need a hint. Sometimes you need to purge, sometimes you need to anoint, sometimes you need to mend, and sometimes to leave behind and forget. Parts of you have to die and parts of you must live on no matter what.

When I was leaving, my mother gave me a sprig of mugwort and wrote a prayer on a piece of paper. I took the Grown Alchemist Persian Rose hand cream with me and mom kept the one with Arnica.

***

Having arrived in Kyiv around noon, I went to an old friend’s place to get some rest before departure: the train was leaving at 7 PM. We had some rosé and salmon sandwiches. She showed me a recent picture of her aunt’s place in Izium: a house with a black hole in it. Then my friend left to help rescue some pets abandoned by their owners and I fell asleep. A few hours later we went to the central station. It was dimly lit and empty. I had never seen it like that. The crowds that had been there during the first weeks were gone. In early March, people would leave their luggage on the platform to squeeze into an evacuation train. In early April, there seemed to be almost no one around. Groups of soldiers. Quiet and solemn people. But the train was full. There were two other women in my compartment: the elderly lady was calm and composed, the middle-aged one was crying all the time. Leaving a place a bit more dangerous than either of them, I still wasn’t feeling like a refugee. Rather like an opportunist. On the train, I was reading D.V., Diana Vreeland’s autobiography.

Having arrived in Warsaw, I checked into a Marriott, closest to the central train station. Filled a bath. Covered myself with YINA Recovery Body Treatment. Cut the ends of my hair. Translated another interview with war victims. Warsaw was covered in snow. The highrise in my window had the pale light of an LG slogan on top of it: “The Future Is Here.”

Having arrived in Berlin, I found out that my father and his colleagues had been rescued.

Those days, I was feeling zero friction with the surroundings, as if I had always been there—but it took me a while to stop shuddering at the sound of airplanes and sirens.

***

"Heaven and earth are ruthless, and treat the myriad creatures as straw dogs; the sage is ruthless, and treats the people as straw dogs. Is not the space between heaven and earth like a bellows? It is empty without being exhausted: The more it works the more comes out. Much speech leads inevitably to silence. Better to hold fast to the void."

Chapter Five of the Daodejing likens humans to dogs made of straw that were used for sacrificial rituals. Over many centuries, there has been a lot of discussion as to what this comparison really implied. One thing seems obvious: it is precisely thanks to this attitude that the myriad creatures would thrive.

Being aware of one’s own replaceability and serving one’s part in an incomprehensible cosmic transformation ritual—isn’t that the ultimate recovery treatment? The pain will always be there, but it’s part of the ritual too. It’s just the pain of transformation.

***

In the Vedic tradition, the first material substance of the universe is formed so that the progenitor has something to sacrifice to his son, the devouring fire. It is an offering that brings the world into existence. Peace requires a ritual offering.

The progenitor’s youngest daughter, Śrī, the goddess of earthly abundance, makes offerings to the creatures that had robbed her, thus restoring her splendor while being able to share it.

Rituals of sacrifice are needed to contain the cyclicity and interconnectedness of generation and destruction. Otherwise, these come in amounts that can be neither contained nor justified. The overproduction of meaning. The incommensurate destruction, ever so meaningless, incomprehensible.

***

One of the 70-year-old dinner knives I had brought with me to Berlin broke when I was spreading soft butter on a slice of bread.