The Penetrated Body

Andrey Shental on development of technologies of penetration into human body and artistic practices of their reflection and description.

Penetration is the condition of modern masculine subjectivity’, claims queer writer Jonathan Kemp [1]. But what if we strike out the adjective ‘masculine’ and universalize penetrability, applying this condition to humanity on the whole? Injected, extracted, exploited, grafted, implanted, incorporated, or interpellated, the contemporary subject is no longer integral, but is open to new biological technologies and molecular forms of control and exploitation that tend to be invisible.

Traditionally, the human body (corpus) has been considered inviolate. For most of history, as Jean-Luc Nancy writes, one body only ever opens another when killing it. [2] The penetrated body is often a dead one, since opening it — as with the tip of a spear or sword — inflicts destruction through blood loss or organ damage. The body is also a discursive armor — a shell, cuirass, chainmaille, corset, or kolchuga — that is joined directly to the human essence, regardless of dualism or monism. The Body, that I tend to neglect as ‘something foreign, something strange, the exteriority to my enunciation’, in fact coincides with my own existence; it equals dasein — my phenomenal being-there. [3] As a theoretical construct, the corpus serves to demarcate the limits of subjectivity, emerging from its surroundings: detaching the subject from the object, the figure from the ground, the I from the Other, the anthropos from other species.

The last century is commonly thought to have been a point of divergence for the natural sciences and continental philosophy. In fact, the way they both treat human flesh and subjectivity may be conflated. According to classical mechanics, two objects — or bodies — could not occupy the same space simultaneously. However, this idea has been overturned. Contemporary physics has discovered that bosons are not subject to the Pauli exclusion principle — the co-presence of two entities in the same space is, indeed, possible. This is just one example of a dynamic first apparent in the long twentieth century. The penetrating ability of X-rays — to pass through matter, exposing the living organism — and the invention of psychoanalysis — announcing the existence of an unconscious — fractured the human subject. If radiographs exposed soft tissues and the shadows of bones without damaging the body, the talking cure penetrated the skull; the receptacle of human consciousness. Theories of the subject further elaborated this penetrability. Asserting that ‘the soul is the prison of the body’, Michele Foucault meant that the notion of a ‘soul’ was an ‘effect and instrument of a political anatomy’ used to discipline society more gently than cruder, physical, methods [4]. This dialectical inversion of container and contained, implemented by political regimes, facilitated — and to certain extent legitimatized — new «immaterial» modes of penetrated subjectivity, through techniques such as internalization, naturalization or subjectivation. In the same vein, the labour of deconstruction continued this work, undermining the closure of any entity — from a human body to a painted object. Jacques Derrida’s critique of the integrity of transcendental subjectivity was based on juxtaposing the alleged phonic ideality of speech and the corrupted spatiality of writing. While, traditionally, philosophers understood consciousness as s’entendre parler (equating self-addressing utterance with understanding), thus guaranteeing the subject’s self-presence, Derrida’s work served to highlight encroachments by the radical ‘outside’ — variously described as difference; arche-writing; trace; pharmakon, etc. [5] Later, Derrida generalised and illustrated this deconstructed subject with a postcard depicting Socrates being penetrated by Plato’s phallic scroll — an image inverting the relationship between the writer and the speaker [6]. If the natural sciences rendered the human body transparent, by making visible the penetrability of flesh by energy, philosophers’ comments on the psyche, soul, or consciousness, rendered it porous — run-through by numerous discursive forces.

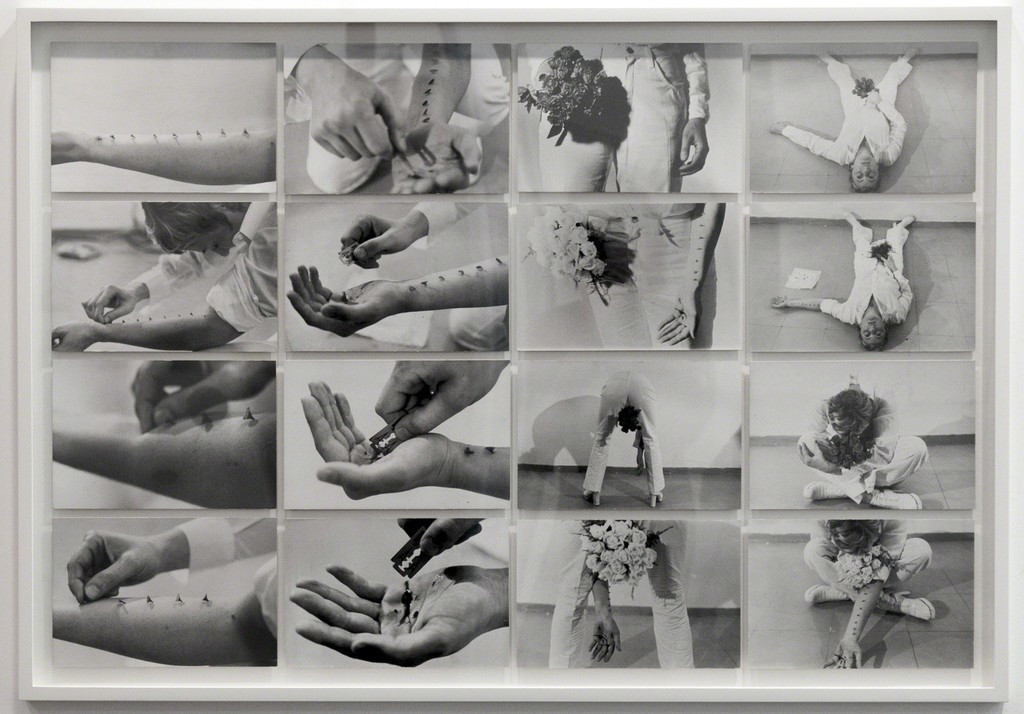

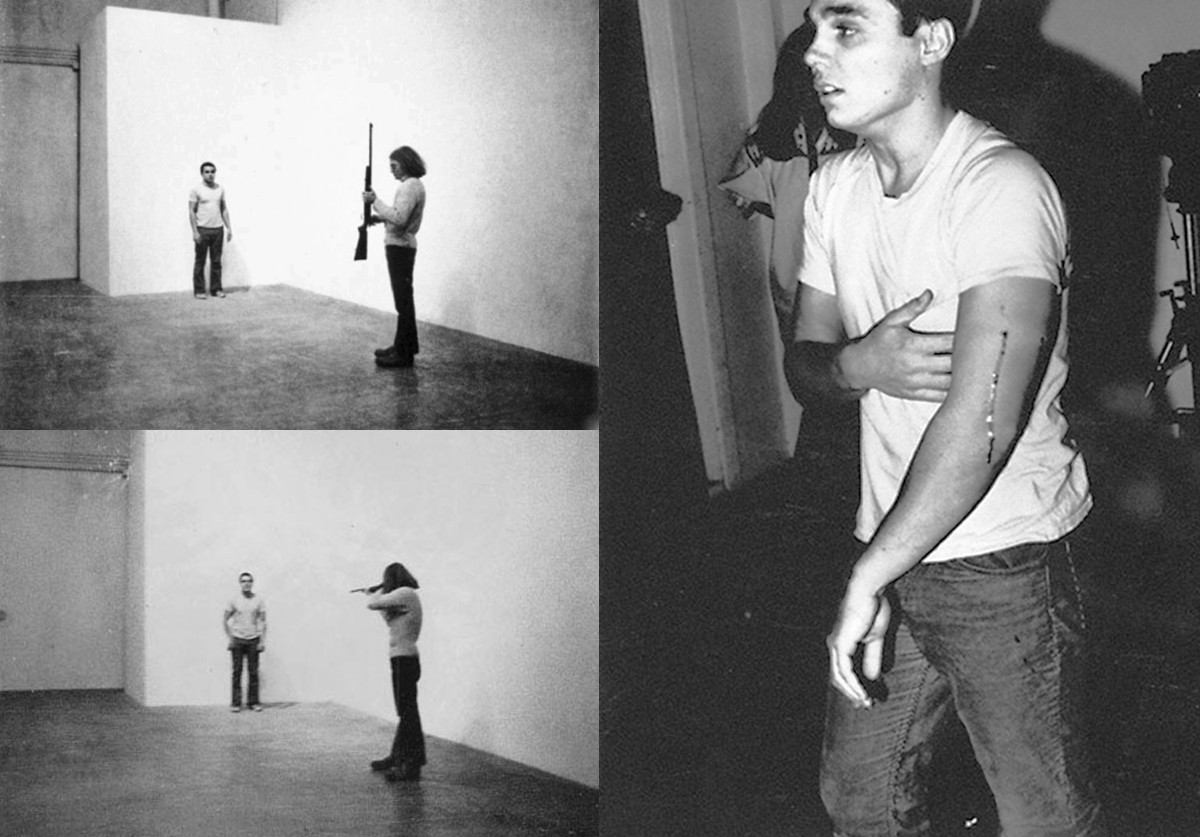

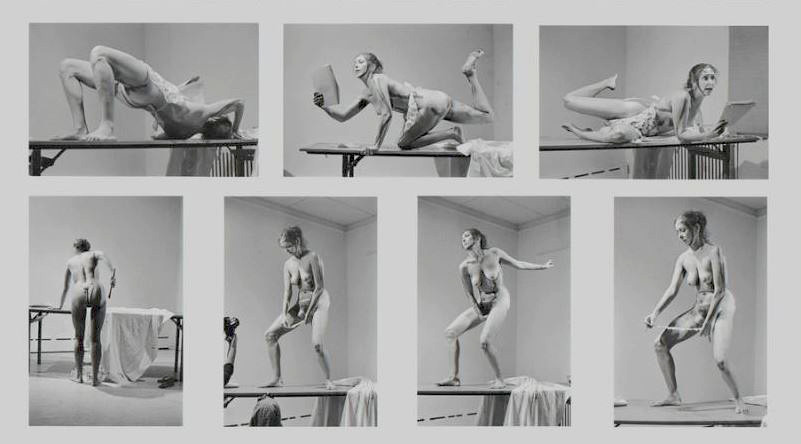

Post-war performance art also put the integrity of human body into question. Indulging in self-mutilation and sadomasochism, artists such as Marina Abramović, Gina Pane, Chris Burden and others tested the limits of their physicality and inspected their bodily interiority. In Shoot (1971) Burden had a marksman shoot him in the left arm. While this action aimed to re-sensitize viewers to the violence of a Vietnam war otherwise mediated by TV-screens, it was also an attempt to re-embody the artist’s figure — to re-establish his presence against a hegemonic imaginary of sensitive abstract painter type consciousness. Rejecting a disembodied — or otherworldly — artistic subject, Burden supplied an image of the artist as fleshiness; a sensate being with anatomy. This perverse medium-specificity, which brutally developed what Lucio Fontana did on canvas, with his buchi (holes) and tagli (slashes) a few decades earlier, radicalized modernist materialist self-critique. However, we can also view these extreme forms of objecthood as the effects of discourse — ‘outside’ entering ‘inside’, repressed physical violence ‘there’ reappearing ‘here’. As Judith Butler wrote: ‘The body posited as prior to the sign, is always posited or signified as prior’ [7]. The discursive power relationships that played out in society — warfare or consumer culture (Burden’s Trans-Fixed, 1974), national identity (Abramović’s Thomas Lips (The Star), 1975), or the construct of femininity (Gina Pane’s Azione Sentimentale, 1973) — constitute the very materiality of these bodies. Notwithstanding the real physical harm recorded in the documentation, the injuries in question stand as signs or inscriptions of deeper acts of penetration — into artists’ ‘souls’, equalizing discipline and physical punishment. Carolee Schneeman’s performance Interior Scroll (1975), reminiscent of Derrida’s postcard, is quite telling in this regard.

Such reflections on bodily penetrability are rooted in the outmoded understanding of materiality underlying Lucy Lippard’s popular notion of art’s ‘dematerialization’ — that his, her claim that objects are ‘becoming wholly obsolete’ [8]. Already, in the late 1960s, the Art and Language group claimed that the metaphor of ‘the dematerialization of art’ is a mere linguistic trick, as any ‘dematerialized’ object is still ‘matter in one of its forms, either solid-state, gas-state, [or] liquid-state. [9] They went on: ‘Matter is a specialized form of energy; radiant energy is the only form in which energy can exist in the substance of matter. Thus when dematerialization takes place, it means, in terms of physical phenomena, the conversion (I use this word guardedly) of a state of matter into that of radiant energy; [it] follows that energy can never be created or destroyed’. 10 Compared to post-war performance art, which was trapped in body dichotomy, certain modernist artists — consciously or unconsciously — were more sensitive to new scientific inventions and discoveries: Olga Rozanova’s ‘non-objective’ semi-transparent paintings, made of coloured paper clippings, allowed the viewer’s gaze to pass through material surface — the flat plane no longer an occluding feature — as if with the help of X-rays. Similarly, Max Ernst’s Ubermahlung or overpainting technique — used, for instance, in The Master’s Bedroom (1920) — is based on subtraction; that is, covering pre-existing images with ink or gouache. According to Rosalind Krauss’s famous interpretation, this technique operates not by creating new images, but functions as ‘the structure of vision and its ceaseless return to the already-known’. [11] From this critical position, the viewer seems to take on the role of an analyst who punctures heavy layers of gouache to disclose artists’, artworks’ and perhaps art history’s unconscious drives.

Radical performances that parse the discursive limits of body permeability through injury, as well as modernist collage or painting tactics that treat artistic material as translucent and permeable, anticipate contemporary practices based on a more sophisticated understandings of penetrability. Following one dictionary of etymology, the word penetrate comes from the Latin verb penetrare, ‘to put or get into, enter into’, and is related to penitus ‘within, inmost’. Also, to penus, the ‘innermost part of a temple, store of food’, and penates ‘household gods’ [12].

Penetration is an act of invading interiority with exteriority, radical inversion and turning insideout.

The act of penetration in this sense should not be reduced to the famous political-rhetorical chiasmus ‘the personal is political’, relating to the bourgeois segregation of the public and private sphere. In fact, in Russian classical poetry ‘penates’ was a popular motif, signifying not merely the poet’s private space, but also the personal, native, homely, sacral and inalienable — something unreachable by the Other. Penates thus implies that which is located not just inside, but deep inside. Not a soul, per se, or unconscious, but something that can not be appropriated by anyone, or anything else — neither radiographs to psychoanalysis. The extreme depth of interiority requires new techniques of excavation.

In modern English, to penetrate, as one dictionary suggests, has a meaning grounded in physics — ‘[to] go into or through (something), especially with force or effort’ [13]. Yet this verb implies at least four additional or subordinate meanings. First and foremost, it is a sexual term that is used to describe ‘the insertion by a man of his penis into the vagina or anus of a sexual partner’ — and could be extended to include numerous non-reproductive practices not necessary implying participation of male partners. Secondly, it has certain economic overtones — such as invading a market with new goods, or accessing foreign consumers. Neoliberal economics still reproduce the phallic image of the liberal ‘invisible hand’. Thirdly, as a ‘mental acumen’ it has a cognitive and even heuristic meaning — that is, to ‘succeed in understanding or gaining insight into’. Derrida, while interpreting the biblical story of Lot, uses the French term pénétrer instead of the usual translation ‘to know’, in order to emphasize its polysemantic character. Fourthly, it has a biological or medical sense, signifying the spreading of infection. Lastly, it is associated with resource extraction, where a penetrometer is a mechanism that measures the liquidity of oil, petroleum, etc. Surprisingly, this seemingly straightforward term reveals affinities between very different phenomena, ranging from sexual intercourse to neuronal mental activity, and from economic interventionism to bodily damage. This process simultaneously brings pleasure, causes physical pain, acquires knowledge and extracts surplus value, like a point de capiton that knots together economic, sexual, biological, informational, and geological forms of exploitation that turn out to be isomorphic and synchronous.

Today we can speak of numerous intersecting, overlapping and coinciding ways in which the human body gets penetrated. First of all, it was the discovery of the DNA sequence and development of molecular biology, genomics and then biotechnology that radically challenged our perception of human bodies. The mapping and sequencing of the haploid human ‘code script’, implemented by The Human Genome. Project, made scientists proclaim Biology a ‘big science’ that could challenge Physics. The very possibility of the genome’s deciphering defined the predictability and manipulability of living organisms — to the degree that genetics is limited by epigenetics. Moreover, developments in neuroscience, particularly ‘the brain-plasticity revolution’, gave researchers and then philosophers clues as to the functionalities of then human brain that were quantifiable, malleable, and elastic. The philosopher Catherine Malabou even projected this principle onto philosophical ontology, defining it in terms of form-giving and the reception of form; also, onto neoliberal capitalism — reducing the doublesided character of plasticity to mere flexibility and adaptability. [14] The third innovation is, of course, linked to new media, information and digital technologies that go hand in hand with the evolution in natural sciences. The invention of binary code that could transcribe any information into a simple combination of ones and zeros led to the digitalization and mathematization of everything, as if material culture was not a product of human will but, quite the opposite, preceded nature itself.

The idea of matter’s permeability, and intelligibility, by means of its calculability — be it literal or metaphorical — fuels new digital, materialist, post-humanist, speculative and queer ontologies whose polemical force supplements the linguistic paradigm of previous decades. The example of Quentin Meillassoux might be paradigmatic in this regard, because of the manner in which this relatively young philosopher attacks traditional metaphysics by appeal to scientific discoveries; specifically, modern mathematized sciences of nature. His landmark concept of the ‘arche-fossil’ — a class of objects whose existence indicates epochs before the emergence of (human) consciousness, undercutting the necessary subject-object correlation upon which the Kantian model depends — is premised upon objective facts established by the analysis of radioactive isotopes to measure the age of rocks, minerals, etc. [15] Thus, the language of mathematization, this transparent, a-subjective and non-metaphysical discourse, unleashes and legitimizes mental penetration into the noumenal world — a world that, since the emergence of Kant’s transcendental philosophy, has been thought unreachable by the continental tradition. But if Meillassoux wants to explain ‘how it is that a formal language manages to capture, from contingent-Being, properties that a vernacular language fails at restituting’, other theorists attempt ‘to assert that Being is inherently mathematical.’ [16] Alexander Galloway, for instance, in a quasi-Pythagorean manner, offers digital code as the basis of contemporary ontology, entailing ‘the making-discrete of the hitherto fluid, the hitherto whole, the hitherto integral’. Being itself, in his view, is undergoing digitalization: ‘Any process that produces or maintains identity differences between two or more elements can be labeled digital’. [17] The real world becomes pervious not only from above, by means of the mathematized sciences, but — being founded on easily quantifiable binary scripts — it is already porous, pitted and lying prone, as if awaiting for the emergence of digital technologies, bioinformatics, computational biology, biological computation or bioengineering.

The new level of scientific and economic mastery over nature that became possible due to matter’s capacity to be informational enables different authors to speak of the capitalization of life, organisms, bodies, body parts, liquids, cells, genomes, etc.

Rosi Braidotti claims that under ‘biogenetic capitalism’ life and zoe — human and non-human intelligent matter — are rendered commodities, for trade, profit and extraction of surplus value. [18] Significantly, the ‘unification of all species under this imperative is based precisely on [the] visibility, predictability and exportability of their genetic resources (the informational power of living matter itself’. [19] Living bodies become like oil wells, from which bio-genetic, neural and mediatic information may be extracted. In a similar vein Beatriz (Paul) Preciado speaks of ‘pharmacopornographic biocapitalism’, ‘sexual empire’, and the ‘somatopolitical regime’ that shifts power’s attention to human bodies. This system is ‘dependent on the production and circulation of hundreds of tons of synthetic steroids and technically transformed organs, fluids, cells (techno-blood, techno-sperm, technoovum, etc.), on the global diffusion of a flood of pornographic images, on the elaboration and distribution of new varieties of legal and illegal synthetic psychotropic drugs (e.g., bromazepam, Special K, Viagra, speed, crystal, Prozac, ecstasy, poppers, heroin), [and] on the flood of signs and circuits [within] the digital transmission of information’. [20] The subject of this regime is not foucauldian homo economicus, but corpus pornographicus — that whose sexual subjectivity is governed by mediatization, biomolecular surveillance and semiotic-technical control of the body’s affects and fluids; pharmacological management, and audiovisual advancement, to name only a few conditions. While in disciplinary societies control was external to the body — but at the same time was internalized by the subject’s ‘soul’ — today we witness that these technics of power injected, inhaled and ‘incorporated’, because technologies are now ‘soft, featherweight, viscous, gelatinous’. Androgel — a hormone that the author herself applied to her body — is paradigmatic of such technologies: ‘The testosterone molecule dissolves into the skin as a ghost walks through a wall. It enters without warning, penetrates without leaving a mark.’ [21]

Whereas modernist art registered scientific and technological progress in terms of physics, one observes that recent artistic practices are preoccupied with biology, chemistry and their derivatives. Instead of foregrounding the physical qualities of pictorial medium, a new generation of artists explores the biochemical constituency of artistic and non-artistic materials. In her work Firm Being (Stay Neutral) (2009) Pamela Rosenkranz filled branded water bottles with different flesh tone liquids, creating what feminist theorist Karen Barad called ‘intra-action’ — interactions where human and non-human objects emerge from their relationships — between these quasi-sculptural objects and the viewer-as-potentialconsumer. The transparency of these bottles, which is supposed to testify to the purity of their content, as a promise of wellbeing, was undermined by the liquid’s opaqueness and uncanny, almost sexually attractive, tint. Since skin is sometimes considered a ‘mirror’ of the body’s inferiority, these corporeal, flesh-toned bottles created a metonymical, toroidal impression: Mineral water is expected to be consumed internally, in order to create the ‘external’ effect of a healthy skin tint. However, this liquid resembles human skin itself. Simultaneously, it looks artificial, poisonous or toxic. Undermining the principle of causation, the work’s dialectic of interiority and exteriority creates a visceral effect: the viewer’s ‘outside’ becoming his or her ‘inside’, and vice versa.

Another example of the bio-chemical turn is Cuts: A Traditional Sculpture (2011–2013) made by (Heather) Cassils. As is clear from the title, the piece alludes to Eleanor Antin’s famous work Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972) — in which the artist documented changes to her body whilst starving herself over 45 days. Cassils inverted this classic work by gaining 23 pounds of muscle over 23 weeks, following a strict bodybuilding regime, using video-training and following a diet developed by a sport nutritionist. To improve efficiency she forcefed herself with meat and eggs (presented in a video) and used steroids that affected her endocrine system. Compared to the artists who have experimented with self-mutilation, that almost entirely vanished from their bodies, Cassils’ training resulted in a tangible and irreversible transformation of her body. In this work nutrition is highlighted as an actant or an agency endowed with transformative power, that besides its participation in cultural practices (and particularly in the formation of femininity or masculinity) — can physically generate new human tissues. Philosopher Jane Bennett writes: ‘if the eater is to be nourished, it [nutrition] must accommodate itself to the internalized out-side.’ [22] This ‘outside’ no longer make inscriptions or leaves traces, but rather penetrates bodies on molecular level, invading the subject’s deep interiority.

These two examples are illustrative of how a younger generation of artists represent or present bodies not as living organisms vested in ‘discursive armors’, but rather as ‘biomediated bodies’ — foregrounding the dynamism of matter and illuminating different biological, technological or chemical actants that participate in the construction of bodies from the inside. This new type of body cannot be characterized by foucauldian inscription or the Derridean trace, nor by psychoanalytic/energetic translucency, because the exterior and interior is longer distinguishable. Moreover, such artworks foreground extreme opaqueness, and incorporeal, nonphenomenal aspects of body (‘corpus, corpse, korper, corpo’ as Jean-Luc Nancy might say). Since new technologies can be injected, inhaled and incorporated in numerous ways without leaving a mark, they speak (at least metaphorically) of ‘dark matter’, ‘deep ecology’ or a ‘deep web’ of human flesh that conceals its own permeability. Biomediated bodies partake of the global flow and (re) distribition of synthetic cells and technical fluids, becoming themselves simultaneously extracted and filled, subjected to nutritionism and extractionism, exploiting and self- (sex) — exploiting. Contemporary penetrations alter the deepest interiority of subjectivity. Beyond psychology, they are psychochemical, bio-digital, and techno-sexual. They inform us that the new mutational global system that no one can label — since all ‘isms’ only describe one-sidedly, and cannot grasp its complexity — gives rise to the emergence of a new bodily typology; a body like plastiglomerate, techno-sperm or Oncomouse. One that is a battleground of different forces: economic, sexual, biological, informational, and even geological.

First published in the 5th Moscow International Biennale for Young Art catalogue. Moscow, 2016

Footnotes

[1] Johnathan Kemp, The Penetrated Male, New York: Punctum Books, 2011, p.1.

[2] Jean-Luc Nancy. Corpus. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008. p. 29.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Michele Foucault. Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1997. p. 30.

[5] Derrida takes aim at the view, attributed to other philosophers, that ‘my words are ‘alive’ because they seem not to leave me: not to fall outside me, outside my breath, at a visible distance’. See Jacques Derrida. The Speech and Phenomena: And Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs. Evantson: Northwestern University Press, 1973. p. 76.

[6] Jacques Derrida. The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. p. 18

[7] Cited in Ibid. p. 6.

[8] Lucy R. Lippard, John Chandler. The Dematerialization of Art. In by Alexander Alberro, Blake Stimson (eds.) Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology. Cambridge: MIT, 2000. p. 46.

[9] Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, Berkeley: University of Californ

[10] Ibid.

[11] Cathryn Vasselu ‘Material-character Animation: Experiments in Life-like Translucency’ in Estelle Barrett & Barbara Bolt (eds.), Carnal Knowledge: Towards a ‘New Materialism’ Through the Arts, London: I.B. Tauris, 2013, p. 158.

[12] etymonline.com/index.php?term=penetrate

[13] oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/penetrate

[14] Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

[15] Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, London: Continuum, 2008.

[16] Rick Dolphijn and Iris van der Tuin. (eds.) New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. Ann Arbor: Open Humanity Press, 2012. P. 80.

[17] Alexander R. Galloway, Laruelle, Against The Digital, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014, p. 52.

[18] Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman, Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 61.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Beatriz Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, New York: Feminist Press, 2011, p. 34.

[21] Ibid. P. 67.

[22] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Durham: Duke University Press, 2010. p. 49.