The space that shapes us: Нow the mahalla system, Borgate ufficiali di Roma, Stalinist architecture influence social consciousness

Abstract

This paper scrutinizes the impact of urban surroundings on human emotions via the lens of Situationist ideas, literature, architecture, Marxism, and actual architectural research. It dives into the topic’s beginnings, giving examples of governments using urban settings to subdue revolt, the negative psychological consequences of our surroundings, and the importance of “drift theory” in city-dweller identity.

The main impetus for studying this topic was a book by the Situationist Guy Debord Psychogeography of the City, whose ideas were based on Marxism. Accordingly, I turned first of all to an important idea of Karl Marx:“It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness” . Which is directly related to Guy Debord’s book, in which he carefully explains the influence of “being” on human consciousness, referring to the urban environment as being.

“Being defines consciousness”

First of all, I would like to grasp the meaning of the famous quote “It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness”. Karl Marx used this idea to describe a much larger process than individual life. Marx was talking about people“s ‘social’ existence — not just the material conditions of life, but also the social conditions. Marxists believed that society shapes a person”s personality and has a significant influence on their behavior, as Marx wrote that “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guildmaster and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, that each time ended, either in the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes".

Having understood the context of Marxist thought, let us move to explore the origins and meaning of the term “psychogeography”.

Introduction to psychogeography

The philosopher Guy Debord is the author of Psychogeography of the City, written in the 1950s. The author described the influence of urban space on society, expressed a subjective view on the social revolution and its preconditions, and developed the theory of urban drift. According to Guy Debord, the space in which a person lives influences his/her way of thinking, each neighborhood has its own atmosphere, which may influence the level of crime in cities. The author gives a reason to think and look at the kind of being we live in, this can be an impetus to build a comfortable environment, which will have a powerful impact on the modern world. After all, according to Guy Debord and other situationists* the prerequisite for an effective social revolution can be a revolution of consciousness, and so the revolution in everyday life itself will consist of creating new situations that change the way people see the world. In other words, social change can take place not by the radical imposition of a different ideology, but in a more “ecological” way — by creating new circumstances in the city in which people can feel at ease. Guy Debord’s definition of psychogeography is:“Psychogeography is the study of the precise laws and concrete effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behavior of individuals. It is the playful side of modern urbanism, through a playful understanding of the urban environment we are paving the way for the continuous construction of the future”.

How the city can be oppressive

Modern architecture and other deliberate environmental organization were seen by the Situationists as being physically and ideologically repressive, which made changing the place necessary (empires tended to loom over the passer-by with their buildings, oppressing in scale, for example the architecture of the Roman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire).

Situationists believed that the urban landscape in which we live imposes a way of interacting with the environment — everyday routines, habitual feelings. For example, thelettrist Ivan Chtcheglov, who coined the term “psychogeography”, noted: “We move within a closed landscape whose landmarks constantly draw us toward the past. Certain shifting angles, certain receding perspectives, allow us to glimpse original conceptions of space, but this vision remains fragmentary” . For example, according to Guy Debord, Paris, during the Second Empire, was redesigned to allow troops to move around it as easily as possible (i.e. to facilitate the suppression of revolts).

Borgate ufficiali di Roma, or “official housing derivatives of Rome,” were built during the time of Mussolini“s regime as a means of addressing the housing crisis in the city and to exert a specific political and ideological influence on the population. These developments were characterized by a specific architectural style, which reflected the Fascist government”s emphasis on grandeur, order, and uniformity. Examples of Borgate ufficiali di Roma include the Esposizione Universale di Roma (EUR) neighborhood, which was built for the 1942 World Fair and featured large, symmetrical buildings with imposing facades, and the neighborhood of Villaggio dei Lavoratori delle Officine Meccaniche, that was built for the workers of the Fascist party’s official factory, with a similar grandiose style.

In the Soviet Union, the government used architecture as a tool to exert ideological influence on the population. One example of this is the Stalinist architecture, which was characterized by grandiose, imposing buildings with a heavy emphasis on symmetry and monumentality. The style was intended to convey the power and authority of the Soviet state and to instill a sense of awe and respect in the population. Examples of Stalinist architecture include the Moscow State University and the Seven Sisters skyscrapers in Moscow, which were built in the 1950s and feature grandiose, imposing facades and towering spires.

Another example is the Narkomfin Building, a residential building in Moscow, completed in 1930, which was designed to be a new kind of collective housing, where residents would share facilities such as kitchens and bathrooms, as a way to implement the communist ideology of collective living. The building featured a modernist design, with large communal spaces and open-plan apartments, and it was intended to be a model for future housing developments in the Soviet Union.

As a result, the urban environment develops repressive, inhuman, and explicitly anti-human characteristics. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Friedrich Engels had already made notice of the isolation and atomization that characterize megacities.

Flexible and rigid settings of the city

The Situationists adopted a position in line with Chtcheglov“s declaration that future architecture will be a tool for altering how we now think about time and space. It will serve as a tool for both action and knowledge. According to Debor, the city”s environment and urban landscape are made up of “flexible” elements: light, music, time, and ideas, and “rigid” settings: the physical structures themselves.

They believed that by manipulating these elements, they could create a new kind of urban environment that would encourage individuals to engage in creative and spontaneous activities, rather than simply existing within the prescribed boundaries of modern society. In this way, architecture would not just be a physical structure, but a means for social and cultural transformation. The Situationists sought to challenge the traditional notion of architecture as a static, unchanging entity and instead viewed it as a dynamic tool for shaping human behavior and experience.

This observation somewhat echoes Velimir Khlebnikov“s ideas on urban space, which he expressed in 1915 when he lamented that “the streets have no rhythm” and said that “the rule of alternating in ancient buildings…the condensed essence of stone with the rarefied nature of air has been lost”. In order to combat overcrowding and alienation, Khlebnikov”s utopia makes use of the elasticity of architectural structures and their adaptability at the whim of their occupants.

On the theory of drift and the sense of self in space

How often do you walk around the city without a specific purpose, just enjoying the walk?

Guy Debord, for example, thought this was very important, so he often went on a long-term drift around the city, as did other Situationists. The theory of drift was soon developed — “one of the Situationist techniques — can be defined as the technique of walking quickly through several different environments. The notion of drift is inextricably linked to an awareness of phenomena of a psychogeographical nature and to the development of creative and playful behaviour, entirely alien to traditional notions of travel and walking”

I first encountered the theory of drift in practice in the summer of 2021, at that time I was writing an article about the psychogeography of a city, and I decided to tell by example what I felt during my journey through places that I have known since childhood. The first place I wanted to go to with photographer was the “old city”*. Walking into the heart of the mahalla I felt very comfortable, the architectural environment felt warm, cozy and at home. It felt like I was in one large house with a huge number of corridors, a friendly atmosphere among the people. We decided to take some photos and continue the journey based on our sensations. After the “drift” we decided to take a few days off to analyze our notes. That same summer, I joined a group of architects researching mahallas and the subsequent “drifts” were conducted together, to make the research more professional. Therefore, the main task of these new “drifts” was not only to study their sensations, but also the structure of the mahalla itself. We wanted to understand what the basic criteria were for building houses and how people communicated with each other.

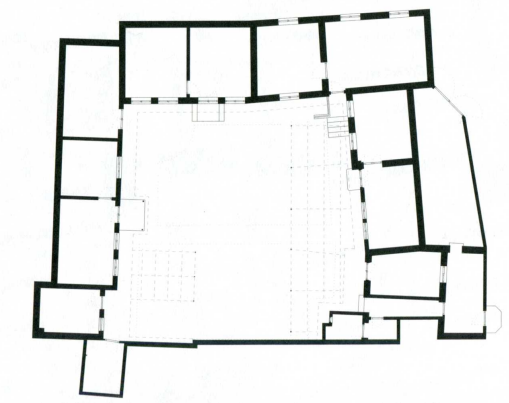

As a result of our observations and research on the archives, we learned that basically all houses in the mahalla are built in a certain way: in the center of the house there is a garden, and on the sides there are rooms with windows and doors facing the common garden. The rooms are designed for all family members (in Uzbek families all relatives live together, even after marriage, so 9-15 people live in the house permanently). At the same time, there are no windows on the sides of the house itself, or there are, but they are very narrow. There are two assumptions why: first, the family is a closed system and everything that happens in it should not be visible to passers-by from the street; second, in Central Asia there were frequent sandstorms and therefore the windows do not face the common street — to reduce dust flow. The mahalla houses themselves are very close to each other and literally built on top of each other; people build them themselves and therefore do not pay much attention to structural and architectural durability. As a result, the mahalla system consists of very narrow streets, random architectural solutions (adopted by the people themselves) and a strong commune within the mahalla. Coming back to the design of mahalla houses with a communal garden, we would like to note that this architectural solution, according to the residents themselves, allows the whole family to see each other all the time, to cook together in the streets; in fact a small garden — strengthens their family relationships and unites them.

The atmosphere in the mahalla is very family-like and traditional-Asian — the strict observance of family values: rituals, weddings, life with parents; gender roles are unequal, and there is respect for elders.

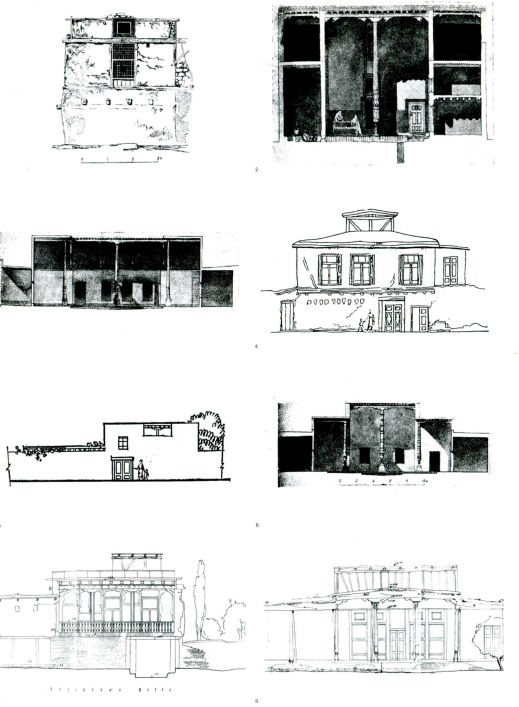

Even during the reconstruction of Tashkent by Soviet architects, the concept of “the garden inside the house” played a very important role in shaping the styles of Tashkent houses. Soviet architects, taking this feature into account, tried to create unique modernist architectural solutions, such as the experimental house by the architect Ofelia Aydinova “vertical mahalla”. This is a 16-storey building divided into four sections with each section having a large ground and a small garden, a solution adopted so that the residents of the flats could communicate with each other and form a strong “commune”.

Later, in the summer of 2022, I did research on the architectural structures of Tashkent in the second half of the 20th century, with the architect Stefano Zeni, in which I again encountered psychogeographical descriptions of urban space, but I realized this after the research.

One of the highlights of Tashkent’s exploration was the Chilanzar district, located in the south-western part of the city. The district consists of more than 20 blocks, most of which were built after the earthquake. In April 1966 a strong earthquake happened in Tashkent and most of the buildings were destroyed because they were built from clay and unstable materials. This event became a landmark for Tashkent urbanism, because after the earthquake an active construction of Khrushchev houses started in the city: houses were built very quickly and, accordingly, quality and comfort were not considered. Thus, most of the panel houses in Tashkent were built and people still live in them today.

While studying Chilanzar neighborhoods 24 and 26 for the general analysis of the city we did not even suspect that we would come across residents' complaints about “depressive” neighborhoods, lack of comfortable living and how unsafe they feel because of narrow streets, overhanging balconies and huge amount of garages. The houses in the neighborhood are 3 or 4 storey and all prefab, the layout is not well thought out as the rooms are very small, the ceiling is low and in some houses the bathroom and toilet are so small that there is not enough space for a large bath and people install a sitting bath. The façade of the buildings has changed a lot in the 50-60 years, as people have privatized the land on the ground floor to increase the living space and built up some rooms, then people from the floors above have built up the rooms directly onto the roof. As a result the buildings look absurd, and most importantly unsafe, as the master plan for the rebuilding has not been approved by the municipality, and the regulations have not been respected.

We met a woman, Gulchehra, who has lived in these houses since their construction. It turns out that these houses were built for a short period (because of the earthquake people had to be resettled quickly and given housing for a few years, and then moved to more comfortable houses which take longer to build), but because of the collapse of the USSR no resettlement took place, and people stayed in these same houses. As a result, the area has not been completed, not thought through to the end, and people are still living with the expectation that they will be resettled and these houses will be demolished.

As I walked around this neighborhood I felt some heavy feeling inside that pressed relentlessly on me, at that time I had not yet interacted with the residents and did not know the whole history of the neighborhood. But I noticed a huge number of garages with the numbers of people to find drugs and sex workers written on them, also this part of town has the highest number of liquor shops and drunk people everywhere. In general, as I found out later, this area is considered one of the most criminal areas. Without realizing all these facts and just observing my feelings during the “drift” I personally realized that it was uncomfortable.

But after a full analysis of the typology of the houses, the social structure, and personal feelings, we were finally convinced with the architect that the architectural environment we studied really did shape the consciousness of the people living in these districts. The same conclusion can be made about the mahalla system, where the architectural environment has united people into a commune for several centuries.

What’s happening now

At the moment, the connection between architecture and psychology and anthropology is only getting stronger, and this can even be seen in the trends of the main architectural exhibition, the Venice Architecture Biennale, where the most topical issues of urbanism are presented. For example, the 2020 Biennale was called “How will we live together?” and architects from all over the world, drawing on their knowledge not only of architecture, but also of anthropology, psychology, art history, politics, etc., tried to find an answer to this question. As a result, the whole Biennale was full of sociological studies, ethnic questions, because studying architecture from that prism reveals a lot of interconnections with other spheres.

I would like to pay a special attention to the anthropology of architecture; it is a rather new science, which appeared in the 20th century, and its main task is the study of cultural interactions and ethnic issues within the architectural environment, which is partly similar to psychogeography. Because the anthropology of architecture is the study of how people interact with and experience the built environment. It is a subfield of anthropology that examines how architecture shapes and is shaped by culture, society, and human behavior.

Anthropologists who study architecture look at the ways in which different cultures and societies design and use their built environment. They consider how the physical characteristics of buildings and spaces influence social interactions, as well as how cultural norms and values are reflected in architectural design.

For example, an anthropologist might study how the design of a traditional African village influences the way that people interact with one another, and how thelayout of the village reflects the community’s social and economic organization. Another example is the study of how skyscrapers and other large-scale buildings are used in modern cities, and how their design reflects the values and priorities of the society that built them.

In simpler words, anthropology of architecture is the study of how people use and experience buildings and spaces, and how these spaces reflect the culture and society that created them.

GLOSSARY

situationists — a member of an international organization of social revolutionaries made up of intellectuals, artists, and political thinkers from the avant-garde (France 1957-1972).

“old city”— after the takeover of the Russian Empire in 1866, Tashkent began to divide into a new and an old part of the city, with the old part inhabited by locals and the new part by Russian soldiers and others.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ENGELS, Friedrich. “The Condition of the Working Class in England”. New York : J.W. Lovell Co,1887

BUCHLI, Victor. An anthropology of architecture. Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2013

CHTCHEGLOV, Ivan and oth.“Situationism: A Compendium”. Bread and Circuses Publishing, 2014

KHLEBNIKOV, Velimir. Us and Home/Works. Moscow: Soviet writer, 1986

DEBOR, Guy. Psychogeography of the city. Ad Marginem Press, 2017

MARX, Karl. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1859

MARX, Karl. The Communist Manifesto. Marxists Internet Archive P.O. Box 1541; Pacifica, USA, 2010