Not a Single Story* or Why Decoloniality Matters and How We Can Make It Visible

*The title of the article was inspired by the TED Talk "The Danger of a Single Story" by the wonderful and empowering feminist and writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. In this conversation, Chimamanda talks about how our lives and cultures are composed of many overlapping stories. And why it is dangerous when only a single story becomes dominantly represented.

- Direction One: Decolonial Advocacy, Manifesting and Pamphleting

- Maikki Friberg

- Elsa Laula Renberg

- Direction Two: Decolonial (self-) Archiving

- Eufrosinia Kersnovskaia

- Heyran xanım [Heyran khanim]

- Direction Three: Deconstruct the Myths

- Курманжан Датка [Kurmanjan Datka]

- კატო მიქელაძე [Kato Mikeladze]

- Direction Four: Decoloniality and Participation in Decision-Making

- Мөхлисә Бубый [Möxlisä Bubıy]

- Marie Reisik

- Direction Five: Engage in Peace Movements and Solidarity with Other Movements

- Լյուսի Թումայան [Lucy Thoumaian]

- Ona Brazauskaitė-Mašiotienė

- Direction Six: Preserve, Maintain and Take Care

- Ivande Kaija / Antonija Lūkina (née Antonija Meldere-Millere)

- Айша Ғарифқызы Ғалымбаева [Aisha Garifkyzy Galimbaeva]

- Direction Seven: Write and Publish

- Nozimaxonim [Nozimakhanim]

- Ғаспыралы Шәфиҡа [Şefiqa Gaspıralı]

- Direction Eight: Engage in Activism

- Алаіза Пашкевіч [Alaiza Pashkevich]

- Софiя Русова [Sofia Rusova]

- Who Has the Right to Give a Name?

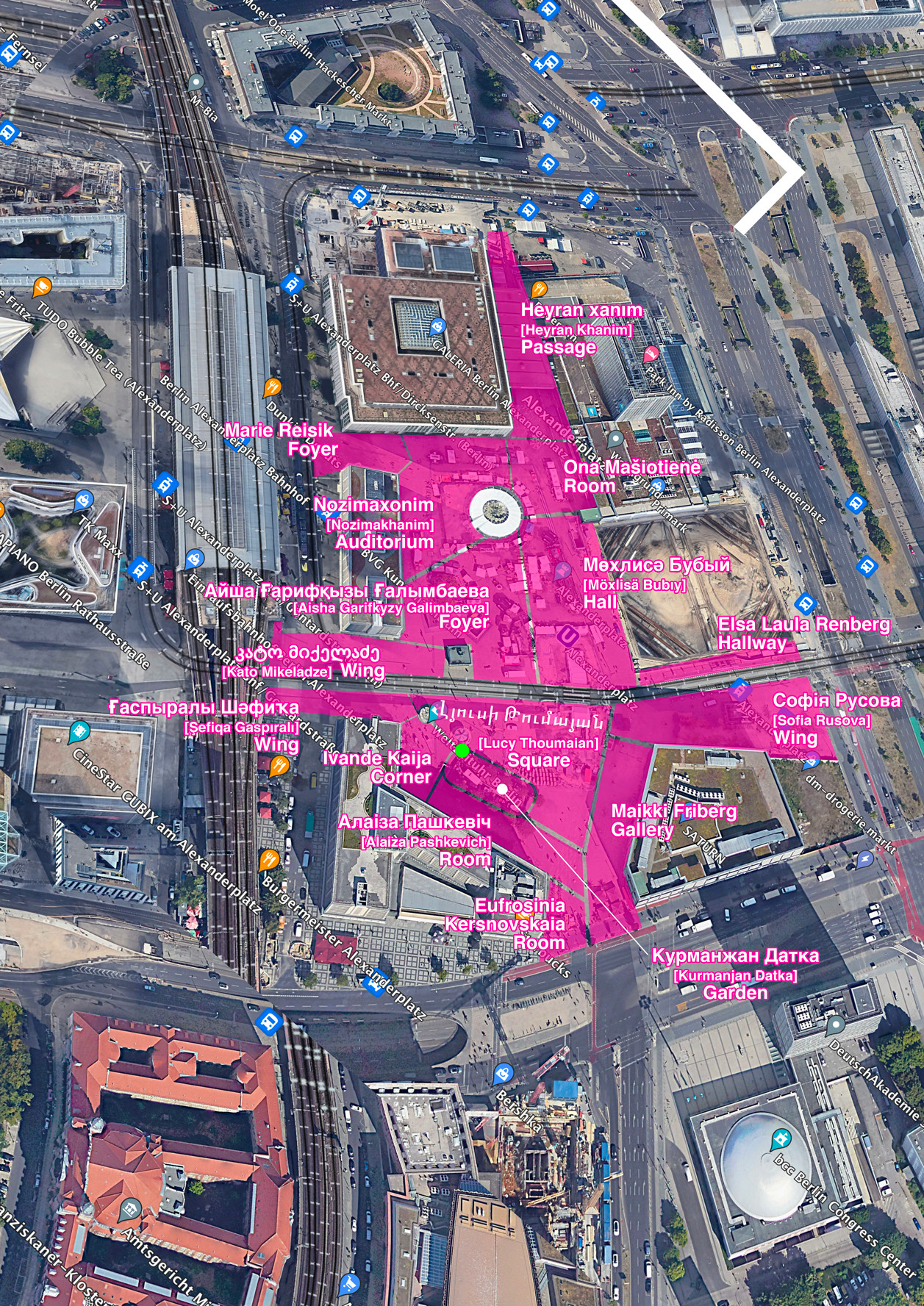

We believe that urban memory should honor not imperial gains, but the memory of people’s yearning for freedom, solidarity, and justice. We are publicly asking the questions: Why has one of the central public squares in the center of Berlin the name of a Russian emperor, Alexander I? How is the process of urban naming connected to foreign policy? And why do feminist names remain invisible in the public space? And of course — what can we do to make them visible? These processes reveal the questions of knowledge production and we would like to invite the audience to reflect on it.

We consider solidarity to be a valuable and necessary factor in a decolonial approach. Solidarity with the theories, practices and movements of other oppressed and subaltern people, both trans-borderly and trans-culturally.

Feminist, queer, anti-racist, migrant struggles are an indispensable part of the decolonial movement.

One of our actions there as an institution is to work on renaming the square Alexanderplatz because it is now named after the Russian emperor and successful colonizer Alexander I. Just a kind reminder: Why Alexander I was a successful colonizer? In Central Asia, during the reign of Alexander I, most of present-day Qazaqstan — the Orta zhүz (Middle) and Ұлы zhүz (Senior) of Qazaq khanates — was seized. We have decided to ask the AI about it. Let Chat GPT answer this question:

“During Alexander I’s reign, Russia expanded its territories significantly through military conquests and diplomatic agreements. Some of the territories that Alexander I added to Russia include:

1. Finland: Following the Finnish War against Sweden (1808-1809), Russia acquired the Grand Duchy of Finland, which became an autonomous part of the Russian Empire under Alexander I.

2. Bessarabia: Through the Treaty of Bucharest in 1812, Russia gained control of Bessarabia from the Ottoman Empire, expanding its influence in Eastern Europe.

3. Congress Poland: The Congress of Vienna in 1815 established the Kingdom of Poland, which was a client state of Russia under Alexander I’s rule.

4. Caucasus region: Alexander I oversaw the conquest and annexation of parts of the Caucasus region, including Georgia and parts of modern-day Azerbaijan.

5. Alaska: In 1867, during the reign of Alexander II (successor to Alexander I), Russia sold Alaska to the United States, but it was during Alexander I’s reign that Russian explorers and traders first established a presence in the region.

These are some of the key territories that Alexander I added to Russia during his reign, expanding the Russian Empire’s borders and influence in Europe and beyond.“

What can we make, so that Other Names could resound in these public and mind spaces instead of generalizing imperial ones? We can make feminine and decolonial names more visible, creating an OTHER ARCHIVE. By other archives we mean creating an archive of alternative stories, voices and perspectives, excluded by the big official historical narratives. One of the most important parts of this direction is orality, the unwritten archives of cultures that transmitted their knowledge in other unwritten ways or cultures in which grammar was violently forbidden by power. It means adding additional voices and making the whole dominant story (single story) more complex. Other archives provide more shades and viewpoints on how we can talk about one thing or another and make the process of knowledge production decolonial.

This is why the Open Air Museum of Decoloniality by de_colonialanguage collective now shows 16 feminist and decolonial names, instead of one royal one. All these women have had relations to decolonial and feminist practices. They open perspectives from which these women’s stories allow us to talk about the history of Russian-Soviet colonialism and its consequences today. And also, about their practices of liberation from the violence of reduction and colonization.

This article and project method works like this:

We have chosen 16 stories that allow us to open the conversation on decoloniality from different angles. We would like to concentrate mainly on the directions for the decolonial discourse, which the stories of these personalities help us to make visible and deconstruct the hidden imperial methods from decolonial positions. All these personalities are of course controversial because every personality is controversial, there is no ideal one, this is normal to be controversial and celebrate the differences. However, this is not normal, when public (hi)stories, discourses or even public spaces are dominated only by one single story — an imperial and patriarchal one. We would like to celebrate these controversies because they allow us to open the discourse, and space for a conversation and debate. We are aware, that each of these personalities can be contradictory and problematic, but unlike the “bronze glossy straight names of colonizers” their stories help us to unfold the anticolonial archives and narrations.

We do not insist on the one and only “true” story. We invite you to share your ideas or views on this or that personality in the comments, even if you agree or do not agree. We also invite you to bring more “unknown” names to this discourse. Let’s break the “one and the only narrative” by making more alternative and powerful stories visible.

Direction One: Decolonial Advocacy, Manifesting and Pamphleting

These stories show how women can be advocates for decolonial voices. Maikki combined educational work, traveled a lot, gave conferences and already back then she was showing what the Russian Empire was doing with Sámi rights. This may be useful, to follow, how Sámi people could advocate for their rights and what they are doing now because they already went a long way in this process. This is also the case where decolonial activists could learn — how to engage and make their agenda visible. The practice of manifesting and pamphleting is a very important decolonial practice! The speeches should be published, in order to spread the discourse. To make a protest sustainable, speak a speech, write a speech, and spread the speech.

Maikki Friberg

Maikki (1861–1927) is a Finnish suffragist, who was advocating for Sámi rights: she conducted educational work and explained how the Russian government’s policy was limiting Finnish autonomy. She traveled widely, promoting understanding of Finland abroad while participating in international conferences and contributing to the foreign press. She was also a peace activist, actively engaging in the Finnish peace association Finlands Fredsförbund. She contributed articles to Finnish and foreign newspapers and founded her own magazine Naisten ääni (Women’s Voice) in 1905 which she edited until her death. She is remembered for her involvement in the Finnish women’s movement, especially as chair of the Finnish women’s rights association Suomen Naisyhdistys.

Elsa Laula Renberg

Elsa Laula (1877-1931) was a Southern Sámi activist and politician. In 1904, Renberg wrote and published a 30-page pamphlet in Swedish “Do We Face Life or Death? Words of Truth about the Lappish Situation” making her the first Sámi woman to have her writings published. Originally, Sámi lived as one large group in a wide geographical area with no national borders. However, as a result of the colonization of historically indigenous territories, the grazing land is crossed by the borders of Norway, Sweden and the Russian Empire. This work discussed several issues that were facing the Sámi, such as their education system, their right to vote, and their right to own land. Renberg also encouraged Sámi women to work and help her in the cause. Throughout the pamphlet, she uses carefully crafted temporal rhetoric to enact resistance to colonization processes.

Direction Two: Decolonial (self-) Archiving

The story of Eufrosinia Kersnovskaia is valid for the whole list, first of all, because it is a female writing testimony about GULAG (an oppressive system by the working camps of the Soviet State). Many of us know the writings by Solzhenitsyn and Shalamov, but to have a huge (anti-)GULAG archive, created by a woman? It is a unique contribution to the documentation. Oppressive systems always try to eliminate alternative testimonials, which is why working on documentation and (self-)archiving, practices of self-writing and self-ethnography are valid decolonial practices. The story of Heyran Khanim allows us to open the talk about forced migration and how Imperial systems easily change borders and force people to move from their homes and change their “national” attributes. We can find a lot of stories like this, and the testimonial by Heyran Khanim is just one of many voices — also poetic one. A female voice who misses the home, only because some imperial men have decided to start another war.

Eufrosinia Kersnovskaia

Eufrosinia (1908-1994) is a female antiGULAG writer, who witnessed the annexation of Bessarabia by the Soviet Union and was deported to Siberia. When she tried to escape, she was sentenced to death. However, she refused to ask for clemency and wrote: "I cannot demand justice, I do not want to ask for mercy". Kernovskaya’s death sentence was nevertheless changed to labor camps. She spent 12 years in Gulag and created an alternative archive, by writing her memoirs in 12 books, accompanied with 680 pictures. The complete text in six volumes was published in Russia only in 2001 after her death.

Heyran xanım [Heyran khanim]

![Heyran xanım [Heyran Khanim], unknown author + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/y-k8dHLzU9QRo54uwdNWtiAbXdZiNDWxTiA1tCotcCM/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2NjZGM2N2E0ZGM5OTQ5YWRmMzEzZGJiMDU1ZjRlYzllOWUyZWIyNjkvc3RvcmUvYzk5ZDM2YjQ5ODk2MzQ1MjY0NjMwZGJjMGI4NTE0NDY0ZDQyM2IwZjcwZDIxNjQ2NTIzMzQ5YmU5MWZhL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Heyran (1790-1848) was an Azerbaijani poet, who in the first half of the 19th century wrote poetry against the violation of rights and the oppressed situation of women. In some of her poems, she protests against evil and social unfairness. Heyran was a forced migrant along with her family. Born in Nakhchivan, she had to move to Iran after Azerbaijan was divided in 1828 by the Turkmenchay Treaty between the Russian and Iranian empires. Heyran lived in Tabriz until the end of her life and continued to write poetry about her native town she could not return to, despite the fact that Tabriz was less than two hundred kilometers away.

Direction Three: Deconstruct the Myths

Have you heard the myths like “empire was always there” or “they have joined voluntarily”? In the early to mid-19th century, Russia gradually expanded its control over the Central Asian Khanates. This process involved military campaigns, treaties, and alliances with local rulers. Russian history tends to show, that the new territories and people were “happy to join the big country”, but in reality, it was more complicated. The stories of Kurmanjan and Kato help us to deconstruct the myths: that the Empire was ALWAYS like this and other people were happy to join it. Officials and scholars tend to say that the Russian Empire transformed into the Soviet Union. However, for many countries and territories, there was a period of independence between these two periods, which we often tend to forget. For example, Georgia declared its independence from the Russian Empire in 1918. This independence was short-lived as Georgia was subsequently annexed into the Soviet Union in 1921. However, during this short period, Georgia had an independent parliament, with for the first time elected women to the parliament, due to the feminist movements. The stories, like those by Kato, help us to make that period of independence visible and valuable.

Курманжан Датка [Kurmanjan Datka]

![Portrait of Курманжан Датка [Kurmanjan Datka], 1907, author unknown + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/D0W64-YFefgCCh8cSOAYyUQOG1UCOYjAnjqt4Rxiv5o/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzA3NTIzZTZlYmQxMWJlNWIxMTNjMTg2NGY0ZTliMGQwMzQ0MjczYjIvc3RvcmUvZjExMGIyZWMyNGYzYmY1NTVlZmE1ZDRmNTYyNWEyNWIwZjc5YjlmYzFlZjM5MDk0NTQxNzQwOWRlNzBlL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Kurmanjan (1811–1907) was the leader and ruler of the Alai Kyrgyz. She was known as the Queen of the South. Had the title of Datka (queen) in the Kokand Khanate and Bukhara Emirate and later Colonel of the Russian Imperial Army. Kurmanjan was a politician in Kyrgyzstan who acquiesced under duress to the annexation of that region to Russia. When Russian imperial troops invaded and seized the territory of the Kokand Khanate, the southern Kyrgyz regions, particularly Alai, continued to remain unconquered. Kurmanjan Datka and her five sons led the struggle of the Alai Kyrgyz against the troops of the "White Tsar". The forces were not equal at all and the Alai Kyrgyz tried to escape first to the territory of modern China, then to Afghanistan. They were unsuccessful. Attempts to play a diplomatic game with the colonial government also failed and Kurmanjan ended her life in a hermitage.

კატო მიქელაძე [Kato Mikeladze]

![Portrait of კატო მიქელაძე [Kato Mikeladze], Paris, 1909, National Parliamentary Library of Georgia + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/PX8sj5DZ62swLBQHfrvdFiZbHyUevp8VMKErOfS4-qw/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2VhNGVlMmY4MmU2MDgwZjk0NTUxNjZmMWNhNGNkYzViZTQ0Mzc5NDUvc3RvcmUvYzFjY2MzMWZjMGY5ZmIzOWZjOTZjNThmZGNhMTQ5M2U3NDM0OTAxMDI1ZTQyMzU3MjEyZjE0MWQzNDE4L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Kato (1878–1942) was a Georgian journalist and feminist who fought for women’s rights from 1916. In order to encourage women to become politically active, she established The Inter-Partial League of Women backed by The Voice of Georgian Women, a newspaper she founded and edited, publishing articles on social and political issues. Thanks to her efforts, in 1919 five women were among the elected members of Georgia’s parliament following the country’s first democratic election, Kato then supported Georgian independence and the political democratic process (first independent parliament) in 1919.

Direction Four: Decoloniality and Participation in Decision-Making

The political questions of “everyday life” are deeply influenced by imperial and patriarchal laws, and it is important to have empowering examples when women can influence social processes like education or the creation of a family. When the Tsarist government began to close Tatar schools, under the pretext that they were destroying the Russian empire, madrasas were closed, and teachers were jailed. Despite the threats, the women’s school continues to work, until 1912. Möxlisä moved to another town and opened another school for women, continuing her educational mission. She was also a strong advocate, that the divorce can be initiated by a woman. Stories like this show how women can be empowered to engage in politics and really aspire to change, also by small steps. The effect like this collects itself and can be very long-lasting if we share the stories of success. This practice of self-organizing is valid both for feminist and decolonial contexts.

Мөхлисә Бубый [Möxlisä Bubıy]

![Portrait of Мөхлисә Бубый [Möxlisä Bubıy], author unknown + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/3Jf8AWWK-N6RURoHBc_W_NAQUbXmVhy-QDoOndZLUdc/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzdmZDE3NGQ4OTQ4ZmNlYWYzOThhMmNkNjUwY2M2MzI0ZTAxMWUyN2Ivc3RvcmUvNTU0OGE3MTdhM2NjZGVmMzdmMTMwZjkyYjQ3YmExYzc0NTQzZWZhZjk4ODdjMmI3NGFjN2Y0OGIzNTBkL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Möxlisä (1869-1937) was a Tatar public and Muslim religious figure, a popular educator. She participated in the First All-Russian Muslim Congress, which took place in Moscow in 1917, where she was elected as one of the 6 qadis of the Central Spiritual Administration of Muslims. At the same congress, decisions were made to ban polygamy, make the wearing of the veil optional, and allow divorce initiated by the wife. This was the first composition of the Central Spiritual Administration of Muslims elected by Muslims themselves, and the first to include a woman.

Marie Reisik

Marie (1887- 1941) was an Estonian teacher, women’s rights activist and politician. She was one of the founders of the first women’s organization in Estonia in 1907, and she founded the first political journal for women, “Naisterahva Töö ja Elu” (“Women’s Work and Life”). Her work contributed to organizing the first Estonian Women’s Congress (1917) which helped to found Estonian Women’s Union (1920). She initiated the emancipation movements across the country and became an active politician. In 1919, she was elected to the Estonian Constituent Assembly and she was the only female member of the parliament.

Direction Five: Engage in Peace Movements and Solidarity with Other Movements

"War is man-made, it must be woman undone", wrote Lucy Thoumaian in her manifesto for peace in 1914. She proposed that women should have weekly meetings with an antiwar agenda. It is a very good example that shows how important it is — to build networks, groups and solidarity circles, and how intersectional work is important both for feminist, decolonial, and antiwar movements. Ona’s story is a good story of a feminist educator — and shows that feminist organizations were not an island, but spread as a network across borders: it is a very good example, of how changes may spread and happen, also among decolonial networks.

Լյուսի Թումայան [Lucy Thoumaian]

![Լյուսի Թումայան [Lucy Thoumaian] at International Congress of Women, 1915, LSE Library + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/WNW6sj-YAM5bg5fDWvWsq8Nog5U_cvLHCgbL1Hzfgtc/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzI2ZTY2NGUwNzNkNjYzMjdhMWVjNjVlNGE1ZWUyNTU2MTMyNTZhN2Qvc3RvcmUvNGM4NGQ4NjAwNmIxODYyMzg0NDI0NGE2N2ZiNmFlZmQxMWU3NmM5MDg4YWIwMjdjODFlNWM5ZTMxZjY2L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Lucy (1890 — 1940) was an Armenian Women’s rights and peace activist. She published a manifesto for peace. In 1915, Thoumaian traveled to The Hague where she represented Armenia at the Women at the Hague conference. She arrived at the conference on 25 April 1915. The day before the Armenian genocide started when hundreds of intellectuals were arrested in Armenia. Afterward, she began working for the League of Nations and continued to work for justice for the victims of the genocide in Armenia.

Ona Brazauskaitė-Mašiotienė

Ona (1883-1949) was a Lithuanian teacher and principal, women’s rights activist and writer. While she was studying in Moscow, she helped establish the Lithuanian Student Society and became interested in the women’s movements ongoing in Western Europe. Becoming an advocate for women’s rights, she was one of the founders of the first women’s rights organization of Lithuania, the Lithuanian Women’s Association, and lectured on the need for equality of men and women, pressing for both women’s rights and Lithuania’s independence. In 1928, she co-founded the Lithuanian Women’s Council, an umbrella organization uniting 17 women’s organizations, which joined the International Council of Women (ICW) as an affiliate member. As a teacher, she organized the first Lithuanian-language girls' gymnasium in Vilnius. Recognized by the independent Lithuanian government with national awards, she was dismissed from her teaching post after the Soviets reestablished authority over the country. She was banned from teaching, and though she was allowed to live on her estate, she and her husband had to volunteer to participate in a kolkhoz, a Soviet agricultural collective, leaving Mašiotienė in a precarious state with little food or firewood.

Direction Six: Preserve, Maintain and Take Care

Oppressive systems destroy archives and testimonials and also prevent subalterns from creating new archives in their local languages and practices. This is a very sad story — what the Russian Empire made with archives and books in the Baltic States. And who knows, if this trauma can be healed? The story of Ivande can open this conversation. Aisha preserved the original Kazakhstani artistic patterns and did very important work: decolonial maintenance. We should not only create something new but also maintain, archive and take care.

Ivande Kaija / Antonija Lūkina (née Antonija Meldere-Millere)

Ivande (1876–1942) was a Latvian writer and feminist, who fought for the independence of Latvia. She wrote articles favoring independence and worked as a social worker. As a supporter of Latvian independence, she was a deputy candidate for the first Latvian parliament and helped to found the Latvian Women’s Association, which was a women’s rights organization seeking suffrage. When the Soviet occupation of Latvia began, Kaija’s works were removed from libraries and her works were disparaged. Though many of her works were destroyed during the Soviet period, they have seen a resurgence lately.

Айша Ғарифқызы Ғалымбаева [Aisha Garifkyzy Galimbaeva]

![Portrait of Айша Ғарифқызы Ғалымбаева [Aisha Garifkyzy Galimbaeva], author unknown + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/X3nvv8qq6p54GZ-awGGiXLqLgSLMcaCsPG5uG4Rx_Pg/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzY2NTFkNWRmNjZmNTM2NWExZWNkN2Q5YjcyYmFiOWI5NTk5NTI2ZjQvc3RvcmUvMGQxMTY3YzZiZGNjOWEyMjczZjAxMTUzYjA1N2NmZmJhNDhhNjcwMzQ0NDEzY2VhZjczOWQ5N2QwOWIyL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Aisha (1870–1924) was a Kazakhstani painter and educator. She is noted for her colorful and realistic depictions of women’s changing position in the Soviet Bloc in the mid-20th century. She saw beauty and interest in the everyday life of Qazaqstan’s people, especially women and family life. Her paintings capture the rich texture of her native land and its people, with a particular focus on women, and their changing social role. She was also the first female photographer to emerge among Qazaq women. Her paintings capture the rich texture of her native land and its people.

Direction Seven: Write and Publish

This is all about a publishing story, and a story about how feminist and decolonial activists can create an infrastructure for their practice: by writing, publishing and spreading information. Only writing by itself is not enough, it is also necessary to take the following steps to publishing strategies and create sustainable practices. Nice stories with feminist editors in chief.

Nozimaxonim [Nozimakhanim]

![Nozimaxonim [Nozimakhanim], illustration by Sening_mening_haqqimiz and @art_anam + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/w7GbuMGbfQzaOfv6v9qQT2k58CqEQ0XICeY6melbEE4/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2JhNWUzZjU3ZTFkN2YwZTYzMTU1ODRhOTdhMjQ5N2FmZjE0Njg3OTEvc3RvcmUvYjI4N2M2NzAwNGZiMTFkMjI2ZWRmOWE2ODBmMDgyY2EyNjI2NDc3Mzk1OWYzYWU5MDRhMGU3NTI3YTNjL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Nozimaxonim (1870–1924) was the first journalist-publicist among Uzbek women. She learned Tatar, Arabic, and foreign languages. She regularly followed the press in Orenburg and Qoqon. She read Uzbek and foreign classical literature, especially Sa’di and Hafiz. Her poems and articles were published in print from 1900. Her poetry and verses promoted education, and culture and criticized ignorance, superstition, and national oppression in society.

Ғаспыралы Шәфиҡа [Şefiqa Gaspıralı]

![Portrait of Ғаспыралы Шәфиҡа [Şefiqa Gaspıralı], 1901, unknown author + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/qrbFDiwFaTirqUeOzGX1bXruaF-MTjD7clC15-w2DRU/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2Y5N2YzZDlkMDRmNTVjZGYyZjBjYzY4ZDVlZDI4MjViMTVkNjlmNjAvc3RvcmUvMjUzMmU2NjU5MjRlNzc3OGVjMTdlZTIyNGJlM2Y2ZjE2NmRmMjcwOTVjOGI1NDZiYjA0MGRmMGViMWU0L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Şefiqa (1886 — 1975) was a Crimean Tatar feminist leader who was editor-in-chief and publisher of the first women’s magazine "Women’s World" writing about the matters of improving the low social status of women in Russia, women’s education and employment. Şefiqa was a member of the Presidency Council of the Kurultai, and a deputy for two terms in the Crimean People’s Republic. She was part of the Jadid movement, a political, religious and cultural movement of Muslim modernist reformers that was destroyed by the Bolshevik government of the Soviet Empire. Şefiqa was one of the pioneers to start a women’s movement because Turkic women living in the Russian Empire were excluded from social, political, cultural and economic life, neglected and deprived of education.

Direction Eight: Engage in Activism

These stories of Sofia Rusova and Alaiza Pashkevich show how imperial oppressive mechanisms force people to leave the country due to their activism. All the same, these stories show how for writing and fighting the regime, people can be accused and forced to leave the country. Through stories like this, we can talk about the practical impact of imperial policy on human life.

Алаіза Пашкевіч [Alaiza Pashkevich]

![Portrait of Алаіза Пашкевіч [Alaiza Pashkevich], unknown author + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/q8HzZyswXcCB9-BzB2Ow-RmiDqVlmo7G3HCyYkwt3D0/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2M2ZGFmNzIyNzUwYjZmNGZhYTY1MGY1OTgwN2E3NjUyNjNiYmFiMmEvc3RvcmUvMjBjNmM0NTQ0MTliYjYwNzBkZGQzNzlhNTRmMDNjMDcyYWUwMjhhYmE2NzQwNDExOTNkYzU2M2NhMmZlL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Alaiza (1876 — 1916) was a Belarusian poet and political activist of Belarusian national-democratic rebirth. Pashkievich was one of the founders of the Belarusian Socialist Assembly. In 1904, she gave up teaching and returned to Vilnius and from that moment on, "the woman question" was an important part of her ideas on social justice. She organized workers' groups, wrote and promoted anti-government proclamations, and took part in debates and political meetings. For her poem "To Captive Neighbors" Russian censorship banned two of her books. The poetess developed the idea of independence of Belarusians from the Russian Empire. Because of her political activism, she was forced to emigrate to Galicia, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Софiя Русова [Sofia Rusova]

![Portrait of Софiя Русова [Sofia Rusova], 1934, author unknown + Other Names action by de_colonialanguage collective, 2024](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/FhJXpXJrnunBu68QbffG8A35NLVkiZjENm6UW0Np28I/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2UyODgwM2JhZmJmYjEyNWYzMjY0NzNiNDQzNjdiMTdlNmMxYWNjM2Evc3RvcmUvZWViMmU4NGQwMTA1ZTNlODhjODQ1Mjc4ODMxZmVkNDc5ODU4ZDRmYWRmM2FiNTBhYzRjNWY2ZGQ5NDY5L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

Sofia (1856 — 1940) was a Ukrainian pedagogue, author, women’s rights advocate, and political activist. Rusova promoted daycare, continuing education, human rights, and the political organization of the peasants. In 1917 she became a member of the Central Council of Ukraine. Rusova was a founding member and first president of the National Council of Ukrainian Women. Sofia was a language activist and defended the rights of the Ukrainian language to be independent of the Russian-speaking domination of the Russian Empire. She compiled catalogs of Ukrainian literature, advocated for education in the Ukrainian language, was active in the derussification of schools, organized courses in Ukrainian studies, and prepared Ukrainian school textbooks. Sofia was arrested and imprisoned on several occasions for her “revolutionary” views and writing. She escaped from Soviet Ukraine in 1922 and settled in Prague, where she taught at the Ukrainian Higher Pedagogical Institute between 1924 and 1939.

In lieu of a conclusion, we want to point out the question:

Who Has the Right to Give a Name?

Our questions on the operation of naming, stretching from Alain Badiou’s designation of this function in “Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil", were rooted in the colonizing function — the dominance of one knowledge over another. One knowledge fills all space without leaving a void. Everything is comprehensible and clear, even if this is the first encounter with a new phenomenon. Even in this case, there already exists names from an extensive recorded archive.

Audrey Lorde highlights the other functions of naming — the manifestation of the invisible, of the unknown. Putting it into language for meaning. As part of this naming of the invisible — working with one’s senses. Careful use of language to mark the space of conversation in which the voice of the unnamed will be heard. And first and foremost naming oneself. The void of the Unnameable will be taken over by the power and you will be assigned a role, agree you or not.

Resist and name yourself. We should name ourselves and be able to hear Other Names.

by Marina Solntseva, Denis Esakov