on togetherness and Living Together

Вы можете прочесть этот текст на русском здесь.

The "Constitution of the Union of the Republics of Russia" by Grigory Yudin, Evgeny Roshchin, and Artem Magun became a topic of many discussions during the "Academy of Political Imagination." Participants criticized the Constitution on several grounds: it established Russian as the primary language while failing to acknowledge other languages of the future "Union," designated Moscow as the new capital, and excluded representatives of decolonial initiatives, feminist resistance, and other political movements from both the creation and discussion processes.

As organizers of the Academy, we believed we had learned from past mistakes by creating a less dense program than last year's. But again we didn't have enough time, and the planned debate on the Constitution never materialized. This text emerged from that lack. Rather than focusing on specific articles of the Constitution, it examines the fundamental principles of constitutional creation itself.

Who has the right to utopian thinking, and how does it relate to law and power? Who is the subject of lawmaking in the modern world? Why is it necessary to follow the principle of "nothing about us without us" when creating laws? How did empires and colonial powers impose their rules and boundaries without regard for the interests of localized groups?

The form of this text itself is a form of critique: Denis Esakov, Kolya Nakhshunov, and Marina Solntseva deliberately preserved its stylistic diversity. The text's uneven language amplifies the authentic voices of those whose family histories and lived experiences bear the imprint of patriarchal and colonial violence.

- Utopia—who owns it?

- What could be the constitutional power?

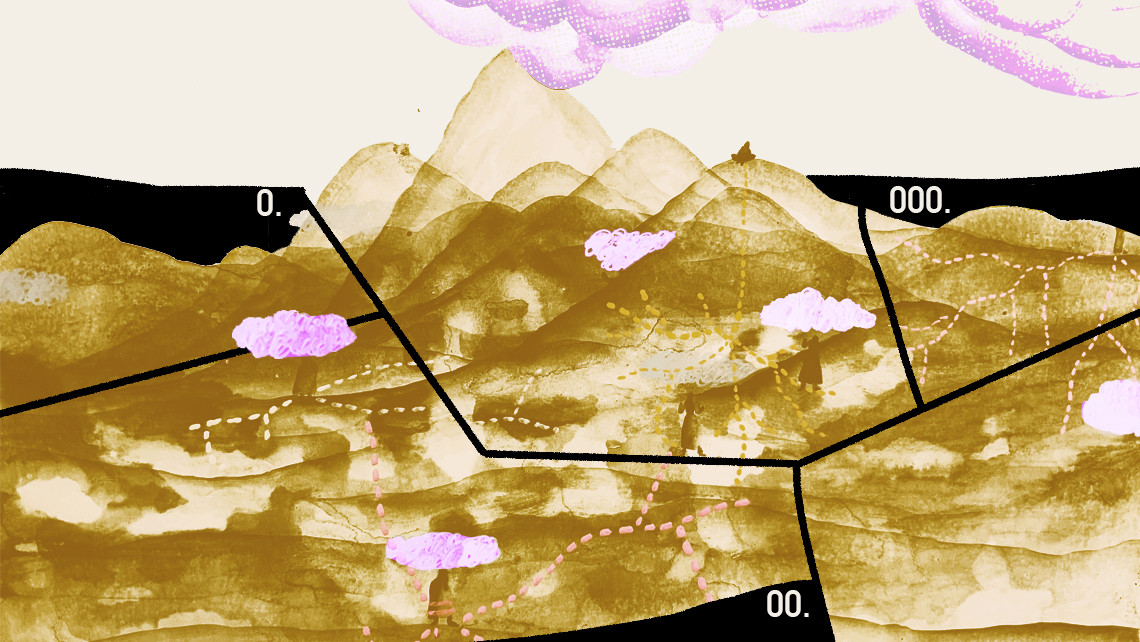

- Me—landscape—You

- White Lines of Not-Togetherness

- Imperial (im?)maturity

- The creation of nations in the USSR

- The Union that never was

- Alternative is possible. Questions to status quos

- Quilombismo—proto-democratic communities

- Mature exes but not really

- Who the World is Fuck?

- Spaces of Togetherness

- Nothing about us without us.

- Utopia—it's us in motion

These different texts have been initiated by de_colonialanguage collective and woven into one fabric of triological text. For such fragmented and composite writing, stumbling is a very natural quality. Moreover, insisting on such stumbling is a truly decolonial action. Because the text is born in the Russian language and translated into English — these are both languages that have become part of our consciousness through violence. They are not mother tongues for many, and the chance to become such is slim. Therefore, the chances of meeting the requirement of a violent language to “speak cleanly and without an accent” are colonial demands. On the other hand, such interrupted, stumbling, unevenness is natural — when the language breaks.

Utopia—who owns it?

There is a zone of nonbeing, an extraordinarily sterile and arid region, an utterly naked declivity where an authentic upheaval can be born.

Black Skin, White Masks. Frantz Fanon

Utopia, or u-topos, is a Greek place that doesn't exist. Does it really not exist? And, if it really doesn’t, why is it at the basis of law? Perhaps utopia is a ‘non-place’ from where the law that substitutes the boundless utopia should grow? After all, the law does not strive to secure a better life for everyone, it only lets a certain someone to appear. Utopia is assigned to a specific place, which belongs to that certain someone, but never to us—to their Other.

Right from the opening passages of ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?' Spivak is warning us that ‘Some of the most radical criticism coming out of the West in the eighties was the result of an interested desire to conserve the subject of the West, or the West as Subject. The theory of pluralized “subject-effects” often provided a cover for this subject of knowledge.’ Thus, the revolutionary form that we thought was our ally turned out to be hiding the regiments of the colonial army that invaded our lands and, keeping civilian bodies at gunpoint, demands us to swear to a ‘common ideal of the future.’

After all, what good have white cisgender men done in all of history?

To begin with: nothing about us without us. Nothing has been written or said about us as it was done without us (we were never even asked!). But also: no one shall dare to say anything about us without us, in our absence. And though we might be invisible to many, it doesn't mean we are not there.

Is inclusion the answer?

If we include as many different perspectives as possible from the start, we will get different results. This is still not a result, but a necessity. Inclusion, agency, and practice. Nothing about us without us. We can begin, for example, with collective writing practices. Or else, we will find ourselves, again, in a situation where three white males would write a constitution for us that we will be expected to live by.

How do you say “constitution” in your mother tongue? Meaning, the kind of bill, an ordinance that would reconcile many different people with each other. I don't like the word “constitution”. It comes from the Latin constituo, ‘I establish’. But who granted this ‘I’ the right to establish? Why is it not You and not We who are establishing?It seems that we must learn-again how to practice assembly with representatives of all those whom the constitution concerns and develop these concepts together—in practice.

Our main question, then, is: how can we voice (express, share-with-others) our (un)willingness to live together-with-others in a common world inhabited by many different others, diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, culture, religion, worldview, gender, sexuality, age, any other affiliations, abilities and possibilities.

This is not a world of law, it is utopia, diversity in its simultaneous inclusivity and (un)settledness.

What could be the constitutional power?

Could it be migration?

How do people deprived of rights appear in the city? We are still living in a world where people with migration backgrounds need to do a lot to get their suffrage, they have to earn it, go through capitalist selection, and prove their worthiness. Should we take a look around and see if there’s anyone else in the room whom we’ve overlooked?

Worldlessness. Thrown into the world hostile to us, we risk losing sight of the Other. Refugees, who, according to Arendt, are ‘the vanguard of their peoples’, are particularly aware of the loss of community and, at the same time, of their responsibility to rebuild or mend it. To create a better world—to do what their predecessors failed to do.

Could, for example, nature be included in the new constitution? And not in the sense of ‘we care about nature’ (hiding exploitation under the guise of toxic care), but to give it an agency—to come up with a law where people listen to nature and align their actions with nature's rhythms, being in tune with landscape rather than “conquering it”?

Me—landscape—You

But with tenderness also,

for we are landscapes, Toni,

printed upon them

as water etches feather on stone.

Our girls will grow into their own

Black Women

Finding their own contradictions

That they will come to love

as I love you.

Audre Lorde

Glissant suggests seeing landscapes, and ourselves as parts of them, as a living organism of togetherness that forms an archipelago of relations. It is a journey from the immobilizing feeling of being aware of the rigid dead structures of unjust power relations to a space of change and other images of a world which holds space for togetherness.

Edouard Glissant's reflection on landscapes:

«to say “self” is to say “landscapes”, because landscapes are not backdrops, landscapes are characters and landscapes are change and differ […] how a whole can be considered as a series of ruptures and not as a harmony of aligning forms».

These are reflections towards the question:

HOW TO LIVE TOGETHER?

Not to suffer in front of a blank page alone, but to appreciate the reflections of many others who have worked towards or around this direction. To look for examples and practices that we can rely on. They are, and have been, and can be a support.

To begin the reflection, it is important to understand that no one is an island, no one is alone in all of that Language. One part of the archipelago of reflections of the Others is Edward Said's understanding of the invention of the “Orient” as a concept and the archive of stereotypes used for dominance and cultural and economic extractivism.

Said points out the problem of togetherness as colonial non-togetherness and does not tell about any possible escape routes from this suffocation space. As Said correctly observes, the word ‘Orient’ was invented in the West without inviting the people who were given this label to the conversation.

Such exclusionary language produces specific landscapes and ways of talking about them. Then, in the same exclusionary way, it creates borders and rules regulating the existence within them. This may be guised under the masks of care, or civilisation, or humanism. But none of those are behind the masks, it’s just words written on them. An empty multitude of words. The way in which landscape and language are developed in an exclusionary way by a small number of people, without including everyone whom it affects in the discussion, is non-togetherness as it is.

It is projecting the interests of those with more power and privilege onto the lives of the Others (or the subaltern, in the words of Gayatri Spivak). It is not about living together, it is about surviving under the conditions which favour the creators of those landscapes, languages, and rules.

“Orientalism is a considerable dimension of modern political-intellectual culture, and as such has less to do with the Orient than it does with “our” world.”

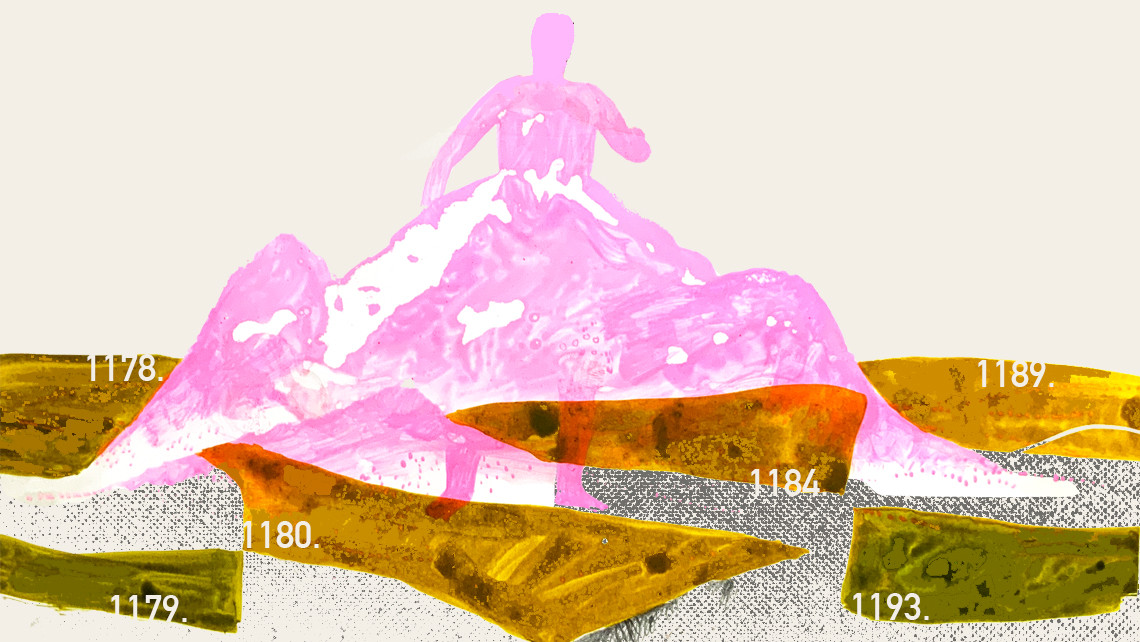

White Lines of Not-Togetherness

How do patriarchy, capitalism, colonialism, the nation-state and gender very cleverly create a network of violence and exploitation, mixing privileges and struggles so cleverly that we are no longer able to deal with them separately? This part of the text looks at just a few of the colonial modes of non-togetherness. There have been many: the straight lines of state borders in the United States and in Australia, the Berlin Conference on division of the African continent, the European partition of the Middle East and the long-standing apartheid in Palestine, the Soviet delimitation of Central Asian political territories, and many others.

What they have in common is the similar colonial logic of non-togetherness: the seizure of territories and populations, their cultural and economic appropriation and rewriting based on the interest and knowledge of the colonist invader. It is non-togetherness because the Others are not righteous participants in this process, but only a resource to be distributed by the colonists, or, at best, they are forced to unconditionally accept the perspective of the metropolia through "negotiations".

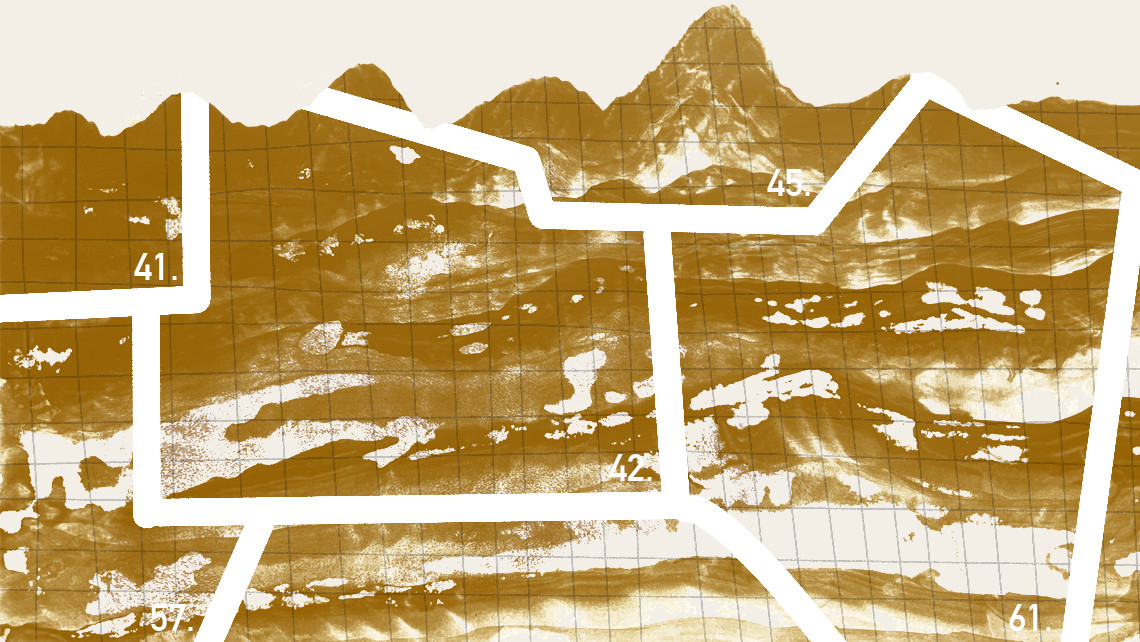

Imperial (im?)maturity

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire owned and ruled lands in the “Near East”. After its defeat in World War I and a number of internal conflicts and wars, the empire disintegrated. Its smaller part became the Republic of Turkey. Some parts, such as Greece, declared independence despite Italy's desire to keep them under its sphere of interest. The remaining bits were disputed by the British, French and Russian Empires. They signed the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement (16 May 1916) which drew rather general common lines across the maps to divide the interests of the four empires (+ Italy with its interests in Greece).

Some of these plans were implemented, and some were substantially revised already at San Remo just four years later. In April 1920, the prime ministers of Britain, France and Italy met in San Remo to agree on the re-division of the “Near East”. Britain received a mandate for Palestine, including Transjordan, and another for Mesopotamia (Iraq), while France received a mandate for Syria, including Lebanon, and part of modern-day Turkey. Mandates of the League of Nations—as if the World (What World? Who is the World?) entrusted the ‘immature’ nations to the ‘mature’ ones. Sounds discriminatory.

And it was. The main interest in the division of territories, as on the African continent at the Berlin ‘Congo’ Conference (1884), followed the borders of natural resources and previous successful conquests of these empires. In the South West Asia and North Africa (SWANA) region, for example, the divided good was oil.

The creation of nations in the USSR

the agent of control

is a white pencil

that writes

alone.

Audre Lorde

I’d like to ponder/fantasise about how we could actually change the way we think? Not to keep redistributing the existing hierarchies (Moscow-St. Petersburg-Moscow), but to glitch them.

The direction of the White Lines distributing the planet's resources in favour of Western empires went on. The next example is the creation of the Soviet republics in Central Asia by Moscow in 1924. At that time it was the language of Tsarist officials called it “Turkestan”, but not only them, some Jadids also used this term for Central Asia. In fact, it was a complex political space of several khanates and tribal alliances with their own histories, cultures, and trade relations, that paid very little interest to their northern neighbour, Russia. But the Colonial Act took place and Central Asia became “Middle Asia” and then “Soviet”. Historians called it “The Great Game” because the second player on the field was the British Empire, which had plans to develop its presence on the continent from India and further to the northwest.

At the time of national delimitation, not all ethnicities had an identity as something separate from others, especially within the concept of “nationalities”, and some were established artificially. From Moscow, the centre of the metropolia, the self-proclaimed Union of Republics created nations, renamed ethnic groups, displaced peoples, and shot those who sought to escape Soviet rule to China. Overall, the ‘Union’ was created by Moscow considering its interests in the resources of the lands seized by the Russian Empire and with no regard for the needs of those who were divided with the red lines of this fake ‘Union’.

The Soviet lego-puzzle of managing the multi-ethnic colonised people had several elements: Russification, consolidation, assimilation, integration and repression.

To justify these colonial actions each empire camouflaged them into progressivist liberating narratives. In the USSR, talks about anti-imperialism were on the facades, but the pillars of its structure were completely permeated with colonial processes from the very establishment of Bolshevik power: seizure and retention of land by military force, forced centralised subordination to the centre (metropolia), exploitation of natural resources and native populations for the benefit of the central colonial power apparatus, epistemicides, mass deportations of ethnic groups, and many more.

In Central Asia, this colonial approach to the division of this land caused many conflicts over resources, primarily water, that still remains a point of conflict between Central Asian countries.

The Union that never was

The Soviet Union is one of the most terrifying empires. I am a subaltern, and I stutter every time it casts its darkest silhouettes on the walls of the red fortress we see in our shared nightmare. Maybe this fear could help us wake up?

The mythical union of independent republics with Lenin's right to self-determination of peoples didn’t ever exist. The revolution and social experiments carried out the transition of power from the Russian Empire to the Soviet Empire. The USSR created an ideology of the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist state-federation which it never managed to become. These slogans stayed on the façades, but on the inside, this structure was created and existed for 70 years precisely as a colonial project subjugating peoples and their lands—also through extractive practices and erasure of Indigenous cultures and languages.

“The main motive behind the delimitation was the Soviet leadership's desire to prevent the potential threat posed by Pan-Islamism and Pan-Turkism as anti-Soviet projects,” Kamoludin Abdullaev writes in his study From Xinjiang to Khorasan (2009). “In addition to splitting Turkic solidarity into ‘national quarters’, the region saw the emergence of Tajikistan, the only non-Turkic republic in the region. [...] The national-territorial delimitation of 1924 was planned and carried out by the Centre. The nations of Central Asia were proclaimed “children of October” and henceforth owed their formation to Bolsheviks and Russians. Hastily drawn borders and further Soviet policies turned the Tajiks, Uzbeks and others from peaceful neighbours into irreconcilable rivals. The region's national elites had to fight each other over scarce resources and the Kremlin's good graces.”

Compare it with the writings of Madina Tlostanova. The Orientalism of the Russian/Soviet empire was an anothered one because it was conditioned by secondary Eurocentrism (2009). Oscillating between [being] an empire and a subaltern, Russia is so hungry for hegemony (cultural, militaristic, value-based—doesn’t matter) that it is ready to strangle the oppressed within. And the more this desire grows, the more sophisticated its internal colonial practices towards the Other become, and the more extensive and brutal its expansion is.

During the national-territorial delimitation, Moscow divided some peoples: for example, the Ossetians were split into two republics, and the Adygs were divided into Adygeans, Kabardins, and Circassians. The Iranian-speaking population of Turkestan was singled out into the nation of Tajiks, and their writing system was changed into Cyrillic. Other ethnic groups were merged into a single nation. Svans and Mingrels were assigned to Georgians, Pamir peoples were put together with Tajiks, Mokshans and Erzyans became Mordovians. The descendants of mixed marriages of Tajiks and Uzbeks were called Sarts; then they, Karakalpaks, and Arab minorities were grouped with Uzbeks in a process of “consolidation” a few years later, in 1936. The metropolis (Moscow) quite literally manufactured some national identities, since a single homogeneous identity, e.g. “Uzbek”, “Karakalpak", or “Sart", did not exist.

“In multiethnic Dagestan in the North Caucasus, there were more than thirty Indigenous nationalities, according to the 1926 census. Only ten remained in 1959, one Russian ethnographer noted.”

These were complex, fluid identities. Most often, identity was defined by birthplace: Bukhorolik—Bukharian/from Bukhara, or by religious affiliation: Musulmon—Muslim, etc. “[In] Central Asia, where Soviet nationality categories did not necessarily have much resonance with people who had historically defined themselves by religion, lineage, region, or way of life (nomadic or sedentary).’’ Some ethnic groups were given new names: the Lamutovs were then called Evens, the Vogulovs Mansi, and the Gilyaks Nivkhs.

Moreover, the process of All-Union Russification and homogenisation required a sophisticated repressive state apparatus. Because a mixed identity is always a predisposition to disobedience. We live in a world of violence of pure forms. Mixed identity—gender, ethnical, whichever—is a threat to the nation-state. Because it never fits.

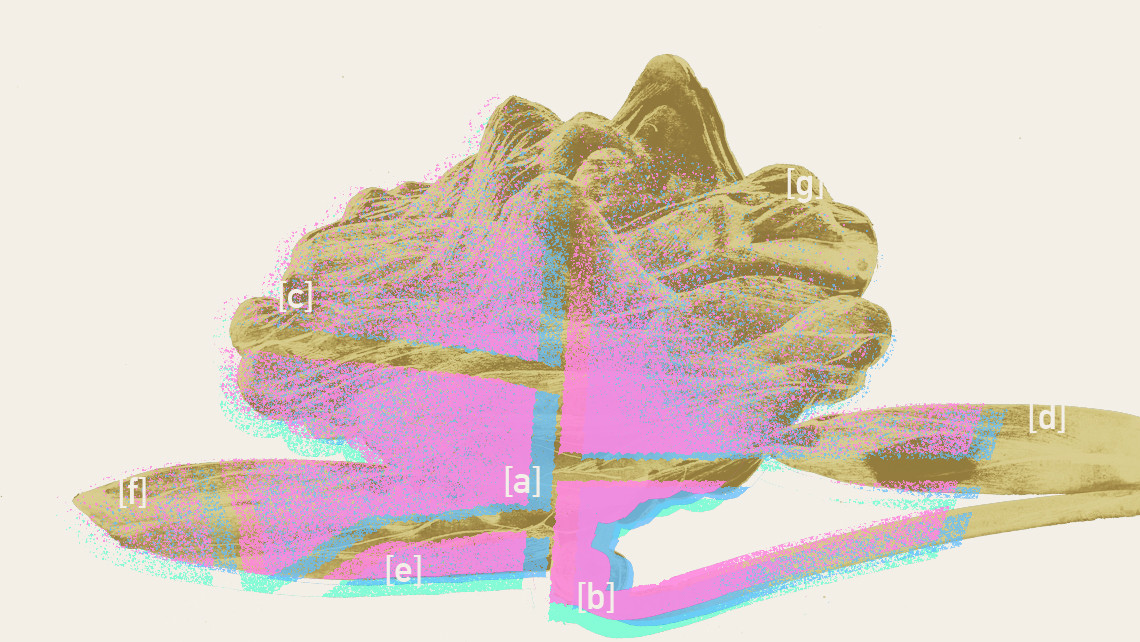

Alternative is possible. Questions to status quos

If repressive structures are so complex, why should resistance be ‘clean’ and ‘simple’? How do we all get to the ‘exit’ modus and find a way out of this colonial structure; when will we take a comprehensive look at this trap in which we find ourselves? What do we do about the nation-state pitfall, where empires disintegrate into nation-states and nation-states reassemble into neo-empires?

The Non-Aligned Movement, which brought together more than 120 countries around the world, has been developing alternative ways of cooperating. The Haitian Revolution and Pan-Africanism, Quilombismo—all these movements offer forms of cooperation that genuinely develop ideas of cooperativity that take differences and diversity into account, unlike the exclusive imperial World Club that speaks for all on behalf of the colonial powers, holding the world together with military, political and economic instruments of subjugation. All these movements are filled with ideas, contexts and problems that have already been described in many books; it is impossible to fit them all into this text, so we will briefly focus on one of them: quilombismo.

Quilombismo—proto-democratic communities

The history of this movement is based on practices of liberation and egalitarian self-organisation. Quilombo is the name of fortified settlements of people who escaped from slave plantations (maroon). Fighting for their lives and freedom, they founded economically and politically independent communities in the forests of Pernambuco (Brazil) and in other places. One such community established the Republic of Palmares which existed for about 100 years (1605-1694) before being obliterated by the Portuguese Empire. There were many such communes and movements throughout the Abya Yala territory (South America + southern North America): quilombos (Brazil), cumbes (Venezuela), palenques (Cuba and Colombia), cimarrones (Mexico), maroon communities (Jamaica and USA).

Quilombismo is a philosophy developed by Brazilian artist, writer and politician Abdias Nascimento (1914-2011), who defined quilombo communities, created by fugitive enslaved people, as societies of ‘friendly and free reunion; solidarity, co-operation and vital unity.’ The tradition of Quilombo struggle and resistance existed throughout the Americas since the first decades of the 1500s when enslaved African populations refused to surrender to European colonisation and oppression and founded new egalitarian proto-democratic forms of governance and organisation. The Quilombi democratic egalitarian experience accommodates race, class, gender, religion, politics, justice, education, culture—all manifestations of social life and different power modes in public and private institutions.

Nascimento wrote the philosophical manifesto of Quilombismo and described more than five hundred years of experience of this movement. He proposed a congress (CONGRESS OF BLACK CULTURE IN THE AMERICAS) designed to create a space of inclusion for all participants in society through different mechanics of participation and representation. At least two such congresses have been held. And now there is growing discussion around creating a Quilombismo Constitution which can only be developed through egalitarian democratic frameworks, not colonial exclusivist methods where the fantasy of preserving one's privileges generates bills and structures of non-togetherness.

Quilombismo embodies anti-imperialist struggles deeply connected to the various strands of the Pan-Africanist movement and maintains radical solidarity with all peoples of the world fighting against exploitation, oppression and poverty, as well as against the inequalities based on race, skin colour, gender, religion, or ideology. As a pursuit and experience of liberation from colonialism, and as a practice of solidarity for mutual liberation, the Quilombist project cannot be separated from the ongoing liberation struggles of Indigenous peoples all over the world.

Mature exes but not really

Can we talk with our friends as with partners, unfolding our intertwined privileges and vulnerabilities openly, evening out that balance? Can we avoid practices of victimisation (and self-victimisation) when talking about colonisation and decolonisation? Is it possible to get out of this crazy global Karpman triangle?

What is meant by “immature” nations? It sounds like a sum total of several discriminations at once—nationalism, ageism, racism, but at a scale of ethnicities and nations. And so it is, multidiscrimination for the benefit of big capital. Other Eurocentric concepts concerning territories of Western empires’ expansionist interests belong to the same framework: “Third World countries”, “underdeveloped countries”, “East”, “New World” and so on.

This dehumanising language asserts that European societies have evolved to achieve the ultimate apex of civilisation—nation states. It contained a looming escape route from the already controversial imperialist ethics, it was no longer ok to be an empire. In no way did it match the humanist project, and neither did the slave trade. And this is where the old demarcation line was drawn—for some reason the Western empires happened to be developed, mature, “first”, “enlightened” enough for national independence.

And those who were colonised were not mature enough (according to the Former-empires-current-nation-states) to become independent nation states. The World (who?) via the League of Nations didn’t grant them a permission to become nation states. But the World (again?) entitled Great Britain and France as “mature” nation states to rule these “immature” societies and granted them the rights to extraction, over-exploitation of natural resources and other extractive practices. And how did the World (sic!) judge the maturity of Britain, or Russia, or France as a nation? How did that same World through the League of Nations entitle Britain to be a nation state? As a matter of fact, it didn't. The League of Nations was an alliance of empires, for the most part (+ Latin American and Asian states, which were then independent from the European empires). An alliance for redistribution of former colonies. It seems like the World isn't really the world, doesn't it?

Who the World is Fuck?

The etymology of another word important for living together—social contract—is connected with speech and speaking to each other, the ability to talk to each other and agree on something. So, first of all, such a contract is an achievement of commonality in speech, the dia- and polylogue that happened.

To speak is to exist absolutely for the Other. (Franz Fanon)

Concepts developed centuries ago are no longer working (and did they ever really work?) In his book “The Racial Contract” (1997), Charles Mills writes that our entire social contract theory, our whole philosophy, was engineered by a very narrow group of white males. The social contract was never intended to be a pact between all people, but rather to be a pact between white men and white men, while other groups (like women or non-white people) were simply excluded from the agreement. This treaty was based on very different, invisible and unwritten principles. The contract that truly ever worked was not social but a racial one.

Concepts invented centuries ago by a handful of white men so deeply define our society today that it seems downright impossible to envision a new way of negotiation and social organisation. If you feel like bringing up the same Hobbes, Locke, and Kant again when talking about the constitution or the social contract, take a moment and think again. By continuing to refer to these ideas, especially when talking about constitutions (at numerous conferences), we continue to reproduce the violent knowledge and world order that does not include many different groups. Were they ever included? Just imagine how many perspectives of women philosophers, and how many other concepts and ideas have never been incorporated into the system of knowledge? No wonder we all get nauseous when talking about the social contract—because it never included us, and continues not to.

At once it becomes terrifyingly clear that the entire framework of international justice, as well as the words and concepts we operate with in news and newspapers, reproduce and consolidate the established system. It seems that the principle that unites most of the modern institutions of power and methods of social organisation is “Include some, exclude others.” Not “Justice”, but “Just Us”. If the structures are visible, we can do something about them, but what do we do if the structures of domination become invisible?

So, who is this “World” that handed out mandates after the First World War, who is this “World” that sets up international organisations, courts? In 2024, the International Criminal Court in the European city of Hague for the first time in the history of this “World” and “international world organisations” set a precedent “when the ICC prosecutor requested an arrest warrant for the leader of a close ally of the West”. I think the answer to this question has already been given by Edward Said: the “World” is a coalition of Western empires that are dominant thanks to several hundred years of colonial dictatorship and extractivism, and this exclusive club refers to itself as “World” and dictates its terms to the majority of the inhabitants of the planet Earth. This assertion by Said is still relevant today. ICC prosecutor Karim Khan recently told CNN that some elected Western leaders were “very frank” with him as he prepared to issue warrants for war criminals Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Galant.

“This [International Criminal] Court is built for Africa and for thugs like Putin,” is what he was told by one of the senior executives. “International organisations” were conceived and built to maintain the balance of power on the planet in a way that favours the exclusive imperial club of the so-called “World” and punishes its opponents and everyone who is deemed an outsider.

Take even the example of how the words “extremism” and “terrorism” started to be used to restrict and intimidate a particular group, whichever, depending on the context—women for their play “Finist Yasny Sokol”, queer people or decolonial initiatives in russia, artists and activists in Germany if they oppose the genocide in Gaza or, for example, the Letzte Generation for their radical eco-activist practices. These terms have been blurred by media narratives, making it possible to oppress any dissenting group just by labelling them as “extremist”. And here, too, it has not been without colonialism.

The UN Security Council, consisting only of China, Russia, the US, France, and the UK (all colonial or postcolonial powers, ha), consistently and step by step adopted a series of resolutions that made it possible to use the word “terrorism” in a repressive way. This is how it came to be that the term “terrorism”, originally applied mostly to the actions of states in the sense of “state terrorism”, is now applied to vastly different groups, becoming a tool of colonial oppression.

The term has accumulated a long history of usage as a political and legal category meant to outlaw anti-colonial resistance and categorise rebellious colonised subjects. The term “terrorism” in contemporary discourse also has racial connotations and is often associated with non-white people. This is an example of how a very narrow group of states (just 5) defined and solidified the meaning of “extremism/terrorism” for the rest of the world. And how the term then came to be applied not to states, but to people.

…

«World», wh/at/o are you?

Spaces of Togetherness

(Radical) intersectionality, or is there another way?

We don’t know.

But we will quote Butler on the fact that now, perhaps, we can only count on poets who might be able to conceive of new holistic principles for the organisation of society.

Exiting these hierarchies: the concept of “ex-colonialism”, [coming] from the word “exit”, roughly means that all of us are in the same colonial situation together, and we need to get out of it together. This will only be possible if we comprehensively reassess the established hierarchies, rather than shifting them from one point to another. We are in (desperate!) need of a new imagination so that we can think about this differently.

Imperial domination with and without masks, and its interests take up not only the space of power, but also the media space, the space of imagination and depictions of the future. This gives an impression that they really are the “World” and they are ubiquitous. Behind these buzzing media facades and institutions of knowledge production, it is not easy to see that the world is much bigger and more diverse than the “World”. And there are alternative forms of togetherness with their histories of development and lots of experience.

How to notice others and, before producing a Shared Space, produce an inclusive Space in which there will be different agents producing ideas of togetherness and ways of making common decisions?

Nothing about us without us.

Intersectionality seems to be the way out. Intersectionality and inclusion. Only by combining queer optics, fem-optics, anti-ableist optics, optics of nature, animals, children, sensual and emotional knowledge, perspectives of different ethnic groups and the Indigenous knowledge, could we get a tiny bit closer to the practice of co-living.

But it is not enough just to possess these optics, it is also important to practice them and create these spaces for inclusion and voices. Not for representation, but for participation.

And the voices of Indigenous peoples are getting louder and louder... I believe that at some point they will become so loud that they will be impossible to ignore. But this is not a cry for help or a call for us to be noticed and taken into account. It is the voice of self-affirming rage, confirming once and for all that we ourselves are able to speak, speak about ourselves and for ourselves.

Practices of imagination, togetherness, doubts, inclusivity, respect, co-operation, listening, acceptance. We need those practices, instead of chess-like reshuffles between the mono-Moscowites. The experience of different kinds of communities and of real togethernesses exists. Whilst drawing on it and on imagination and openness, it is important to first create the spaces of togetherness and only then to move on to co-formulating any agreements for Living Together.

Utopia—it's us in motion

So who owns the utopia? Where will we live together if the images of the future are designed by the state, or by the invisible hand of the market, or by ilonmask, or by wscm? To envision a world of diversity, we must think in a utopian way—which is the path to other places where Togethernesses exist.

To whom utopia belongs? To us! It is important to create alternative images of the Future. It is important not just to Think, but also to talk about the future.

Utopia is neither an object nor a goal. It is not a dream. Utopia is what is missing to us in the world. Our utopia is a search for interconnection and totality, but in a way where we don't forget any component of the world when we think "world". And so in our world today, utopia is never complete. It is what is missing. [...] we are capable of grasping utopia as an endless necessity because, when necessity is endless, it ceases to be a necessity that corrupts and a necessity that oppresses. It becomes a necessity, an urgency, that liberates.

Édouard Glissant

Dystopian thinking allows us to predict the worst case scenario, the risks, and the worst possible option. But at the same time it is very easily instrumentalised via fear and apocalyptic narratives, like, “we're all going to die, so we must run, save [money], save ourselves, do something, аааа-ааа-ааh.”

Utopian thinking, on the other hand, is what remains in times when everything around us is changing and breaking at an insane pace. If we are living in a time of change, when very old and solid—one might even say fossilized—hierarchical structures are breaking down, then all we have to do is carry on through this whirlwind and imagine. Imagine some new ways of togetherness. So that this imagination then leads to the very first steps in a different direction. Because utopian imagination is the most sustainable thing.

And if Glissant's reflections may appear abstract, they are reinforced and concretised by Eduard Galeano:

Utopia is on the horizon. I move two steps closer; it moves two steps further away. I walk another ten steps and the horizon runs ten steps further away. As much as I may walk, I'll never reach it. So what's the point of utopia? The point is this: to keep walking.

Eduardo Galeano

Utopia belongs to the oppressed & the subaltern, so it is important that we—ourselves—think, dream and talk about that utopia. Otherwise someone will speak about us—again. The imaginative space of our utopias is one of the spaces of Togetherness, in which there is one place for those who have been suppressed, erased, deported, Russified, integrated by colonial systems. Utopian thinking allows us to take another step and go Together far and long.

For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.

Audre Lorde

Credits and references:

Mixed text: Denis Esakov, Kolya Nakhshunov, Marina Solntseva

Visual essay: Olesya Gonserovskaya

Editing: Nikita Sungatov, Anna Mikheeva

Translation into English: Sasha Zubritskaya

Discussion and comments peers: Javokhir Nematov

Inspiring texts used as dialogue space during writing and discussion:

1. "O Quilombismo" — Exhibition at HKW

2. Said, Edward W. (1978). "Orientalism"

3. Glissant, Édouard and Obrist, Hans Ulrich (2021). "The Archipelago Conversations". Isolarii

4. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. (2010) Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea.

5. Edgar, Adrienne. (2022). "Intermarriage and the Friendship of Peoples: Ethnic Mixing in Soviet Central Asia"

6. Мингбаев, Нурали. "«Размежеванная» Центральная Азия и трудности региональной интеграции". CAAN

7. "Decolonizing Constitutionalism Beyond False or Impossible Promises". (2024)

8. Cachalia, Firoz. (2018). "Democratic constitutionalism in the time of the postcolony: beyond triumph and betrayal"