The Latex I Live In

For those few who have watched “Queer Japan” in some secret or forbidden way (it has never been officially shown anywhere in Russia), the name Saeborg will be familiar…but for most of my readers this name is a mystery. This interview is a small loophole that will allow you to find yourself in the world of Saeborg and escape a little from our event flow. From myself I will add only a couple of words that allow, at least a little, but to introduce the artist to the Russian audience.

Saeborg works exclusively with latex suits, arranging extremely flamboyant performances with an emphasis on physicality and sexuality. The majority, who are still somehow used to distinguishing the colorfulness and brightness of some Japanese artists, can peck at this bait and move no further, branding the author with a bunch of labels… which do not suit her at all. The peculiarity of most Saeborg projects lies in the fact that it skillfully excludes the belonging of a person to its own species, of course, these are still anthropomorphic animals that behave according to human nature, but this kind of detachment allows us to look at ourselves from the side — the biggest and an unacceptable value. And the longer this feeling lasts, the less circus and fun it has, but more horror and cruelty. Entertainment has long been based on bloody bread and spectacle, we are used to this, as well as not complicating our lives with such thoughts, Saeborg twists our perception, allowing us to look further and deeper. In general, our conversation is about ways to learn new things about yourself, about freedom, which, as it seems now, is becoming alien to us, and, of course, about the role of the spectator and audience.

While we were preparing this interview with Saeborg, she received one of the largest art awards in Japan, the Tokyo Contemporary Art Award. Сongratulations to the artist!

The interview was taken at the end of February

Special thanks to Saeborg for her time and efforts, and to Joe Boxman for help translating from Japanese.

Interview with Saeborg

Gendai Eye: As far as I know, your very first projects were not yet costume related. Can you tell us more about your very first projects?

Saeborg: Before I began working as Saeborg, I majored in oil painting while I was in art school. I soon felt that I had hit a dead end with oil painting and ended up focusing my energy on doing fun things instead of devoting it to my studies. For example, I would go to fetish events in latex costumes back when I was still a student.

At first, I bought latex pieces off the rack to wear to these events, but soon I began special-ordering different custom-made pieces I had designed. This led me to eventually start making them on my own.

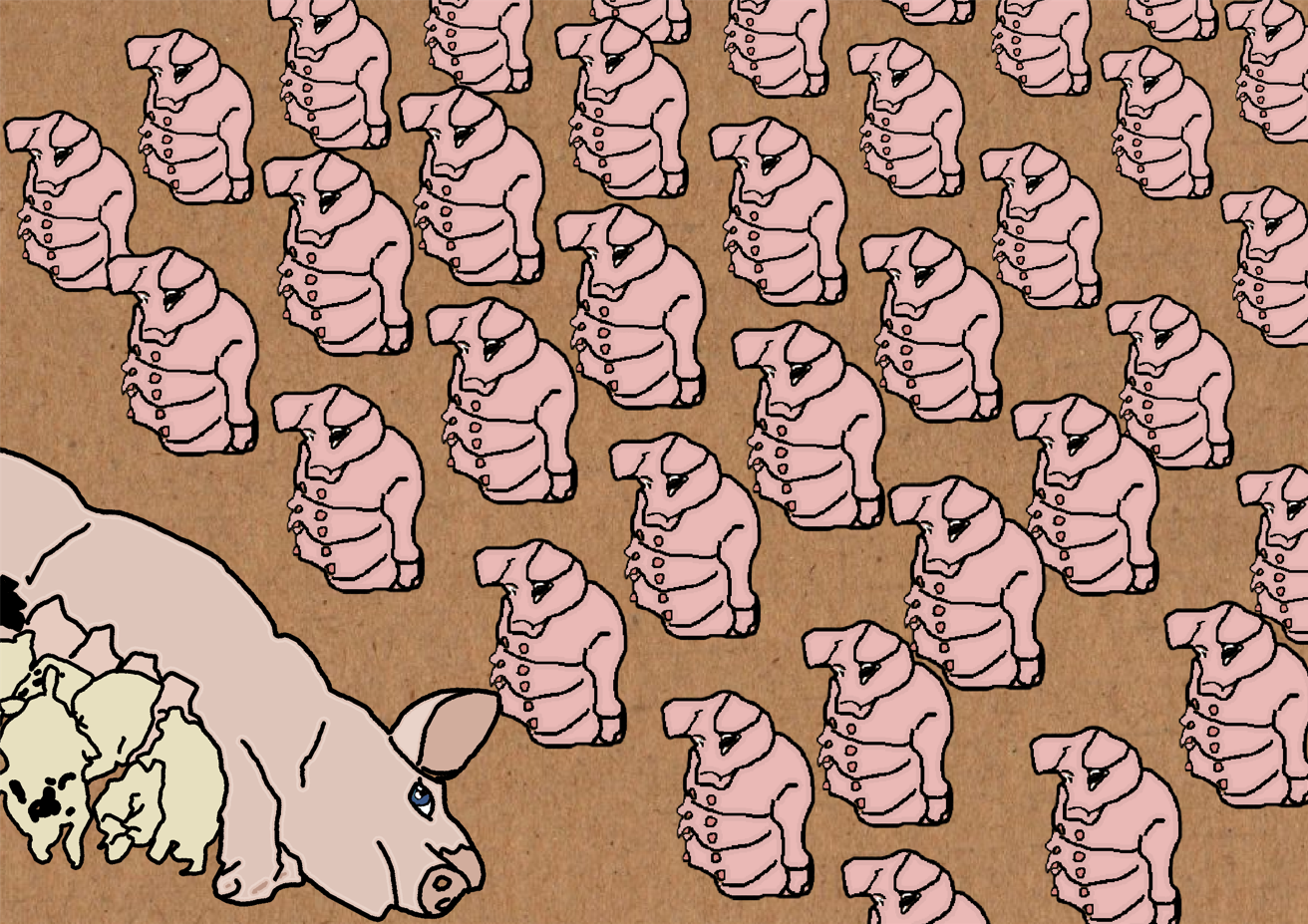

GE: I am very interested in how you manage to implement such layering in your costumes? How long does it take you to create one costume? How did you work on a big pig for Pigpen?

S: The latex costumes that I make are made for me to wear specifically. This means they have to fit my shape pretty exactly. I start by making a half-size model of myself, and then from there I add clay on top of that to build a model of the suit, which I use to make a pattern and then the suit itself. In the case of UltraPork, I started out by experimenting with a 1/6th scale latex model before building it at full size, but other than the size, there isn’t actually much difference between the process for making a costume and making a huge pig. It takes a significant amount of time to get the shape just right in either case. If I’m trying to make something that I’ve never made before, I have to be sure to build in time to experiment and fail and start all over, so I have to set aside at least six months to create each new character.

Pigpen

GE: Is it important for you that you are in costume during the performance? Or are you not always on stage and other people can do it for you?

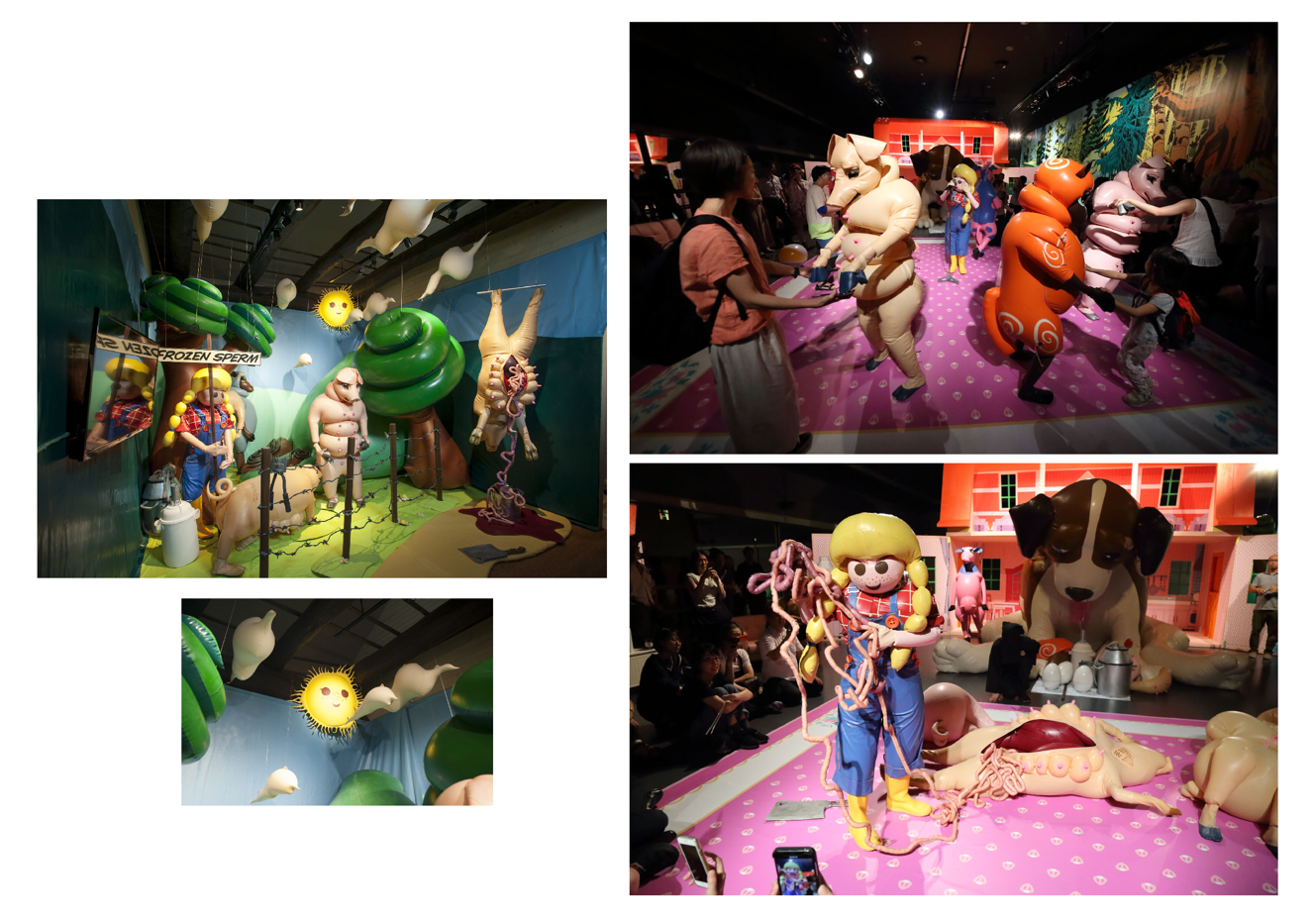

S: The costumes I make aren’t ones that you can just put on and take off by yourself. That means whoever wears the costumes needs to be helped by a staff of caretakers. Every performance or installation comes with its own unexpected challenges and setbacks, so I do everything I can to provide support behind the scenes during shows. We have a hard time finding enough performers because they have roughly the same measurements as me to be able to wear the costumes. On the other hand, I always find that these performers also have so much to teach me, so it’s always a valuable experience to support other performers when they wear the costumes.

The only time I get to wear them myself is when there are no time restraints on anything so I can take as much or as little time as I want. Whenever there is a situation where I don’t have those kinds of time restraints, I’ll be the one wearing the costumes myself.

GE: I could not help but notice, but in your performance with fly-men, you also have conventional puppeteers who support small flies, as if it were a bunraku theater. And these are practically the only characters who, although completely in black, are still people. Can you tell us something about this element in your stage practice?

S: That’s a phenomenon in Japanese performing arts known as kuroko. Essentially, in this context there is an agreement between the performers and the audience to pretend that these stagehands wearing black do not exist in spite of their obvious presence. It’s a type of suspension of disbelief.

They care for the performers and support the production overall from behind the scenes. The costumes I make end up being very restrictive for the wearer to the point that the performers become unable to care for themselves while wearing them. They need to be cared for when it is time for the actual performance, so most of the time I am one of these people providing support and care behind the scenes. Wearing these costumes doesn’t make the performer a full and complete cyborg, but instead, in a sense it exposes the weakness of the body.

This all ties into the origin of my name as well: Saeborg is a portmanteau of my real first name (Saeko) and the word cyborg. While a cyborg might seem like it would be strong, it is in fact a heavily distorted body superimposed upon the self, created when what was originally there has been stripped away and those lost aspects are supplemented with something else.

I found this structure to be really interesting, and that’s what led me to create House of L, which places more of a focus on having the audience play the role of caring for the performers in the suits. By having the audience take part in caring for the costumed performers, they also realize that they are in fact being cared for as well.

GE: Many, in order to feel freer, try to get rid of any masks, misinterpretations of themselves, on the contrary, you dissolve in a suit that allows you to forget about who you are. How do you feel about these two ways to realize yourself in public and artistic space?

S: There are a lot of things you can learn in the process of masking who you really are. When people share time together in that space with the performers who are in this vulnerable state because of the costumes they’re wearing, they also let their guard down and often find it easier to express their true selves.

The performances are like rituals in a way, and the audience always brings something of themselves to them as well. The most magical moment of a performance is when you can see that chemical reaction taking place between what I am trying to express and what the audience brings to the performance. I always try to create performances that have something to offer people—I want them to get something out of it—but I feel I am often the one who gets the most out of it.

GE: How much more difficult would it be for you to realize yourself as an artist if you were not using a costume, but acting on behalf of a woman artist? Does your method of creative expression influence the perception of you?

S: I think it definitely has an impact.

For me, what I wear is an extension of my own skin, and so in creating these suits I am in a sense crafting a second skin that constitutes this other distorted and oversized body. I use latex because of its strong adhesion to the body, a fact that allows it to synchronize nicely with various suits, and also because of the way that the artificial nature of latex can transcend categories like sex and age.

I’m a big fan of James Tiptree Jr., a one-time CIA agent who found success as a writer in the world of science fiction, which was still heavily male-dominated at the time, avoiding some roadblocks by hiding the fact that she was a woman. She was one of the first authors to ever address the theme of sex in science fiction.

I think I could see myself doing something similar, working in a way where my face isn’t necessarily revealed.

Cycle of L

GE: For many, latex is associated exclusively with sexual culture, but you bring it into a slightly different orbit, where everything terrible and human is hidden behind cute and funny. How do you avoid stereotypes when working with this material? Are there any stereotypes or role models within the community itself that you would like to go beyond?

S: While I’m biologically female, I’ve always been extremely resistant to having stereotypes imposed upon me based on that. I think I was just exhausted by having to perform, so to speak, knowing the whole time that what I was presenting was not the real me.

This eventually led me to the decision to become something other than human. This was based on the premise that pornography is only effective within the same species (that is, dogs are only interested in dog pornography, and birds are only interested in bird pornography, for example), then in order to avoid becoming the object of sexualization by people generally speaking, I would have to reject those ideas of woman-ness. In other words, this inverted structure makes it possible to utilize this kind of exaggerated or excessive sexuality without being especially exciting to people who are usually excited by human pornography. I suppose that in a way I create these suits and performances as part of an effort toward new gender expressions and freer sexuality.

GE: Do you meet with criticism of your projects in Japan? Is it possible to imagine that in Japan, a costume will become a part of everyday life, and not just a specific group or community? How much does homophobia and social prejudice affect this situation?

S: It’s not easy for society to accept perfect freedom, but I believe that part of the reason art exists in the first place is to help people feel freer.

I can only hope that my art provides this feeling for people.

GE: And the last question. What’s the suit of your dream? And where do you manage to store all your costumes, are you running out of space?

S: I have an entire room in my house dedicated to storing latex, so that’s where I keep everything. Since most of the suits I create are inflatables, they’re big while they’re blown up, but once you take the air out of them, they don’t take up so much space. Since they’re made to transform as well, they can be disassembled to a degree for easier transport. This makes it possible to create a portable barnyard and things like that.

My absolute dream project would be to expand the Saeborg world to something like a Saeborg Land, including all the suits for the characters that would populate it.