"When I started doing contemporary music, the way I listen to classical music changed a lot."

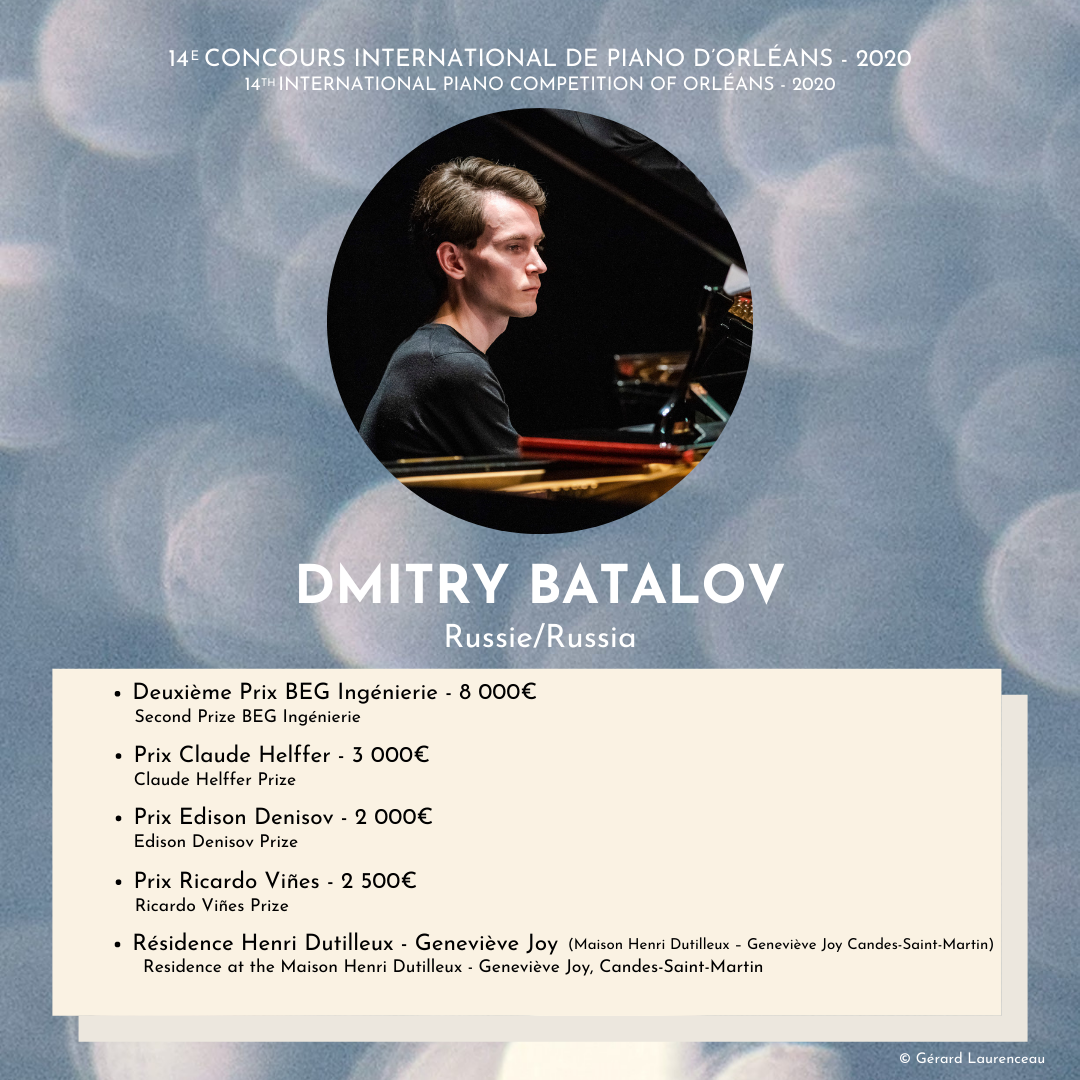

Dmitry Batalov (b. 1997) is a Moscow-based pianist and musicologist who has recently won the second prize of the International Piano Competition of Orléans 2020 as well as four other prizes. He studied at the Central Music School in Moscow and is currently completing his education at the Moscow Conservatoire with Natalia Trull (piano) and Grigoriy Lyzhov (musicology). He is a regular member of the Reheard Ensemble and Praktika Theater’s Ensemble. He has given the Russians premieres of pieces by Beat Furrer, Marco Stroppa, Mark Andre and others.

Marat Ingeldeev talks to Dmitry about his early musical experiences, his participation at the International Piano Competition of Orléans 2020, the nuances of contemporary competitions, the state of contemporary music in Russia, his thoughts about the year of 2020, the role of the technology and how it has influenced music-making.

Marat Ingeldeev: Could you tell me about your earliest experience with music and how you became a musician?

Dmitry Batalov: It all came down to a series of happy accidents really. I was born in Moscow into a non-musical family. Some distant relatives had phenomenal voice skills despite having no musical education. The first music I heard was Soviet bard songs, which my mother sang to me when I was a baby. We also had some compilation albums of classical music, and the first work that really impressed me was Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. It showed how touching music can be. At the age of 5, I began studying piano at a music school in Zhukov, Kaluga Oblast. The teachers there were not particularly helpful, so I had to learn things my own way and somehow developed an ability to sight-read. I started participating in local competitions, but had no idea that I would become a musician as my family wanted me to get a ‘proper’ education.

MI: What was your next step in education?

DB: Once I graduated from my music school, I had no piano classes for two years. I then randomly stumbled upon the recordings of Natalia Trull, whose playing was very powerful and inspiring. At that time, I never imagined that someone’s personality as a performer, rather than a composer, could have such a strong impact on me. I also found out that she was teaching piano at the Central Music School in Moscow and began dreaming of studying with her, although I still didn’t think I belonged to the ‘right’ class of musicians who get in. By pure chance, someone I knew organised a consultation lesson with Trull for me, and as a result of this meeting, I got into the Central Music School and subsequently into the Moscow Conservatoire.

MI: What about your interest in contemporary music? How did you get involved with it?

DB: It was a gradual process through the music of Hindemith, Barber, Enescu and Messian. I was always interested in playing repertoire no one else did. The change of environment happened in 2018 when I was invited to participate at the Gnesin Contemporary Music Week, an educational project for students at the Gnesin Academy. During the festival, me and my friends founded the Reheard Ensemble and performed many chamber pieces together. Our friends helped us find opportunities for initial concerts, and after our visit to the International Young Composers Academy in Tchaikovsky-city, the amount of concerts we gave and pieces we learnt grew significantly. At some point, I started meeting more people from the contemporary music circles, which broadened the potential spectrum of opportunities. Ivan Bushuev from the Moscow Contemporary Music Ensemble and Natalia Cherkasova from the Studio For New Music were of particular influence to me.

MI: And what about your musicological practice? Do you still actively research?

DB: Musicology has already fulfilled its mission in my life as it has introduced me to contemporary music, which wouldn’t happen otherwise. It was mostly musicologists who introduced many new names to me and taught me how to listen to their music. I don’t really consider it a practice of mine, but it gave me a lot of valuable skills. I believe that it can be very helpful for many. Writing papers is definitely not my thing.

MI: Let’s now talk about the International Piano Competition of Orléans 2020. What was the preparation process?

DB: I never was a big fan of competitions since I prefer learning new pieces instead of practising the same programme. Once the rules of the Orléans competition were announced, I began the search for the pieces. I knew the competition would be difficult, but I was very excited to give it a go. The first pieces I learnt were Enno Poppe’s Thema mit 840 Variationen, which eventually wasn’t included in the programme, and Edison Denisov’s Signes en Blanc. Some difficult pieces, such as Tristan Murail’s Territoires de l’oubli and Berio’s Sonata took a long time to master. Overall, the preparation took me one and a half years. I look at this period of my life as not simply preparation for the competition, but a chance for personal development. I was enjoying learning new material and it felt very natural. Sometimes, I used to forget that I had a competition to prepare for. In December 2019, I was happy to know that my application was accepted. We also had to finalise our programmes, and last minute I decided to include Stroppa’s Prologos: Anagnorisis I, but I had not received the score by that time. Once the score arrived, I realised how incredibly difficult it was and immediately began spending a lot of time on it. The fact that the competition was postponed to October 2020 allowed me to learn the piece at a more comfortable pace.

MI: What were the outcomes of your participation at this competition?

DB: It reassured me that I am involved with the music I truly need, and that I have found my own niche since at first I wasn’t sure that contemporary music would interest me that much. I had a lot of emotions after the realisation that I had won the second prize. Also, the fact that there were suddenly more concert opportunities and that I made money from playing ‘strange’ music was a good sign to carry on. Some of the prizes I won include solo concerts in the future. I was also invited for a residency at Maison Henri Dutilleux in 2021, which had to be postponed to an unknown date. I’ll be living there, practising, talking to people and looking at birds for a month. At the end, I’ll be giving a concert. I also learnt that I should plan better.

MI: How different was this competition from a classical one? I suspect that the atmosphere was more friendly than in a classical setting.

DB: I have not been to many classical competitions, but the atmosphere was certainly different. We were playing in a beautiful concert hall on a regular grand piano and were judged by a regular jury, which might easily pass as a regular competition, but it wasn’t tense, perhaps due to the specifics of this strange year. There were only 7 people who made it into the semi-finals and were invited to come to Orleans for the following rounds. We began researching stuff about each other, and it was such a big relief to finally meet everyone in person. I was struck by how quickly we became friends. There aren’t many contemporary competitions after all.

MI: Don’t you think the fact there aren’t many contemporary competitions is not a cause, but the result of little competitive aspect in contemporary music?

DB: That’s true, but also the fact that there are not many people who are willing to prepare a long programme consisting exclusively of contemporary pieces. Regular competition participants can’t promote themselves without going to competitions, but contemporary performers have other ways to become known. There was one British competition, but it didn’t get enough funding in 2017. There was another American one, but it closed down in the 90s. Often, funding is the biggest issue.

MI: Speaking of different countries, have you noticed any differences between working in Russia and France?

DB: I haven’t really worked that much abroad, but I hope I will be able to experience it more during future concerts or projects. I don’t think countries make any differences. It’s all about the individuals and how they prefer working. What really differs is that our Russian environment is totally not equipped for contemporary music: we have to wait for months for the scores to be delivered, there aren’t contemporary scores in the libraries, there are only 2 contrabass clarinets in the whole country and there aren’t many rare percussion instruments either.

MI: So, it’s more about our post-Soviet razrukha (ruin/devastation)?

DB: Our razrukha is very strange as it’s more about practical things I mentioned above. Russian people are not baffled by this. These are the ‘nuances’ of our cultural spirit. Generally, the enthusiasm compensates for the lack of money, but we all know pure enthusiasm won’t take us far.

MI: Are there any pianists who inspire you?

DB: Apart from my brilliant professor Natalia Trull, I try to look up to some established pianists such as Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Maria Grazia Bellocchio, Florent Boffard and how they have organised their professional life, including the balance between solo and ensemble work.

MI: Let’s now talk about the past year. How did 2020 affect you on a personal and professional level? Were there any particular positive/negative aspects?

DB: I am generally not affected by any radical change. I know there is not much to do about it, and I pretend this is how things are supposed to be. One positive aspect was the ability to take a break and reflect. Our busy lives don’t usually allow it, but this time it was a global sign, which was much-needed in my opinion. There is now time to practise without any rush or deadlines. On the one hand, it’s harder to self-oragnise, but on the other, the lack of deadlines allows for a deeper immersion in your work. I also began practising pieces I normally wouldn’t have time for.

MI: And what about negative aspects?

DB: I am not a very sociable person who often needs to meet people, so it wasn’t particularly tough for me. I adapted quickly and enjoyed staying at home doing the things I could.

MI: Many people began working with fixed media and putting on online performances, lectures and talks. Do you think that technology has affected our music-making and music industry?

DB: There are definitely great things I would like us to keep in motion after this lockdown, such as online educational events. However, I am not very keen on the idea of online chamber music-making. For example, the final competition project involves recording the piano part of Poulenc’s Sextet, which will be added to the wind quintet in post-production. It’s not particularly difficult for me, but I don’t want to pretend it’s regular music-making. However good the technology can be, I think that communal music-making is all about being together and feeling the same energy. Natalia Cherkasova once told me that true art can only be solo art, perhaps a duo or a trio if you manage to become one entity. Regarding online concerts, they work as long as they are for solo instruments. I myself recorded solo music for an online concert during lockdown. I don’t think that music must be heard in person. It’s just about how to make it sound right.

MI: Don’t you think it is another, potentially new, type of expressivity?

DB: That is definitely the case as long as it is composed specifically for an online performance. It is a good stimulus to compose new works. Our ensemble organised a call for scores to gather pieces for such an online performance. I welcome all new forms of music-making as long as it’s part of its intention. However, pieces which don’t originally cater for that simply don’t work, at least in my opinion.

MI: And what about piano music in the 21st century? How do you see it?

DB: I see a certain tendency taking place, namely a separation of two art practices: performing and composing. I think if the composer can’t more or less perform his or her music on an instrument they are writing for, it won’t be as good as the music of the composer who knows how to do it. Take classical pieces for example, most of the piano repertoire was written by pianists. If we speak about contemporary composers, Murail, Stroppa, Furrer are not concert pianists, but they have an educational background and know how to play relatively well. Most importantly, they have their own physical experience and perception of the instrument. You don’t need to be a virtuoso, but as long as you have your own physical interpretation of the instrument, it will come across in the music. I think that this comes down to changes in the educational processes. Of course, there are exceptions, but in my experience whenever I find a new piece to play written by a young composer, it turns out that they can often perform it themselves. I wouldn’t want the link to disappear.

MI: Have you had any experience of playing with electronics so far?

DB: I haven’t had much experience with electronics yet apart from one piece. I think I have now become comfortable with most instrumental techniques of the 20th century and working with electronics is my next step. I am really looking forward to it. I asked Vladimir Gorlinsky if he would be interested in reworking his piece Accent sequence for piano and relay. It also involves some improvisation. He thought he could come up with some new performative elements. It might cause some injuries so I am saving up plasters for myself.

MI: What contemporary music have you been listening to recently? Are there any composers you would like to work with?

DB: I like Murail a lot, although I’ve explored it enough for now as I managed to learn all his piano pieces. I haven’t yet performed all of them on stage, but I am just waiting for that opportunity. I love the music of Furrer, Poppe, Stroppa, most Italian composers, in particular Berio and Donatoni. For me, Mark Andre has the most remarkable ear as a composer, and I am really looking forward to working with him in Darmstadt in 2021. I would also really like to work with Lachenmann. I heard that working with Poppe and Stroppa is a fantastic experience. To be honest, I’d like to learn from most of the living composers I have mentioned before.

MI: Do you play or listen to classical music? Are there any names which inspire you?

DB: When I started doing contemporary music, the way I listen to classical music changed a lot. It seems that I started to understand it better. For example, my love for Schubert grew even stronger and he became my favourite Romantic composer. Generally speaking, I like German Romantic piano composers, such as Schubert, Schumann and Brahms. I have a difficult relationship with Beethoven. It is only now after playing contemporary music that I understand how hard you need to work on his music. If I could pick a few composers to live with on a deserted island, it would be Bach, Schubert, Ravel and Mussorgsky.

MI: Do you have any non-musical hobbies?

DB: I like the visual component of our existence and enjoy taking pictures, although I rarely find time for it now. Also, finding out about new photographers and visiting their exhibitions.

6 December 2020