The occupied territories of Sakartvelo: the infrastructure of Russian military bases and the kidnapping of people along the occupation line

Modern wars have long gone beyond the boundaries of ground, air, cyber, or infrastructural and resource-based interventions. War no longer occurs between societies but within them—fighting over institutions, culture, systems of governance, and social contracts. It is far more than the conquest of territories. To win a war is to control the environment.

We are coming to understand that there are no spheres of private life untouched by war. War unfolds in non-military domains.

DYNAMICS 2024–2025:

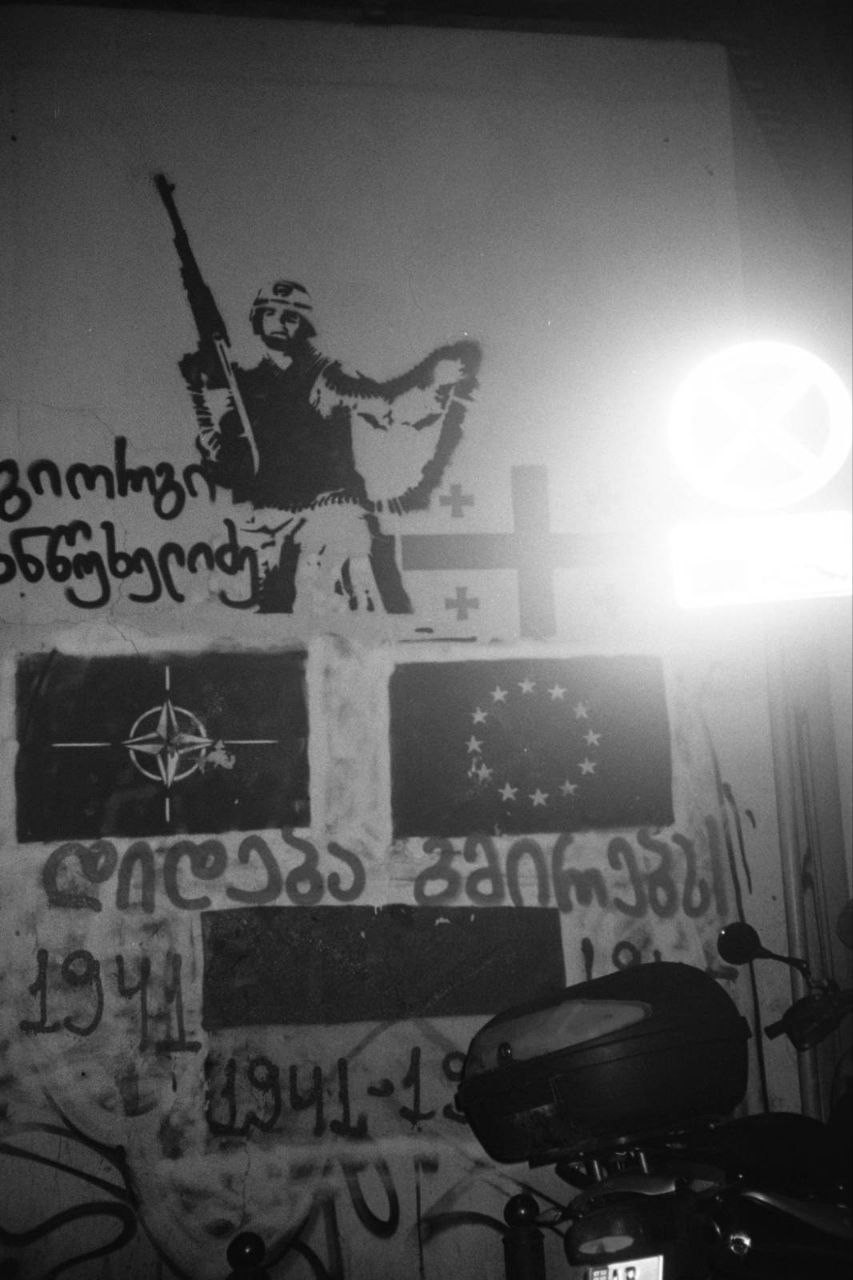

On October 29, 2024, protests erupted in Sakartvelo against the ruling party. They were initiated by students demanding a change of government and the dismantling of the ruling oligarchic regime of Ivanishvili, calling for fair re-elections. The protests quickly spread across the country, finding resonance and support among a wide range of social groups.

Three days earlier, parliamentary elections had taken place in the country, the results of which were falsified. The dominant party in parliament, Georgian Dream—led by the pro-Russian oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili—violated voting procedures, secured an advantage through forged and bought ballots, and gained an official parliamentary majority.

It is worth noting that international election observation bodies (OSCE) identified no apparent problems and justified the falsification.

Meanwhile, the Batumi–Tbilisi highway was paralyzed by state-run minibuses transporting public sector employees and villagers to vote, and later, to participate in staged demonstrations supporting Georgian Dream. In some municipalities, the reported voter “turnout” even exceeded the official population count. The cost of purchasing a signature from residents of remote and mountainous regions averaged around 200 GEL (approximately $80).

The organized opposition offered no clear plan of action, issued no demands, and made no statements of international significance. It announced that it would prepare a “Plan B”—after which it disappeared from view, while nationwide protests began to erupt.

Earlier, on July 9, the European Commission in Brussels suspended Georgia’s accession process to the EU, amid a series of laws adopted by Georgian Dream. This became one of the key catalysts for protest sentiment. In particular, the legislation targeting “foreign influence and funding” triggered widespread unrest among the citizens of Sakartvelo. The first major protests in 2023 were connected precisely to this law.

Many European funding programs were suspended, including those supporting and developing the army, military training programs, and the overall military-industrial complex of Sakartvelo. Indicators of Western business investment also declined, while several members of Georgian Dream are currently under international sanctions.

The context of this decision stems from the sticky diplomacy of Georgian Dream’s leadership. The population of Sakartvelo interpreted their loyalty toward Russia as a shift away from the previously preferred course of European integration. The ruling party, like former president Salome Zurabishvili before them, maintained a stance of “neutrality” regarding the war in Ukraine, avoiding both strong statements and direct assistance to Ukraine. Moreover, economic and infrastructural cooperation with Russia increased: direct flights were resumed, a shadow export system was established to circumvent sanctions targeting the Russian military-industrial complex, and loyalty was reinforced through questionable international alliances with Turkey and Iran. All this stood in sharp contrast to the mass street demonstrations in support of Ukraine—since some of the largest civic actions in solidarity with Ukraine took place not in EU countries, but in Sakartvelo.

November 28 — The Prime Minister of Georgia suspended negotiations on EU accession until the end of 2028.

December 14 — Presidential elections in Sakartvelo. Georgian Dream nominated and inaugurated its sole, uncontested candidate — a football player with some awards but no higher education whatsoever, not even outside his field.

During Georgian Dream’s rule, several legislative acts were rapidly adopted to strengthen political and economic ties with Russia, further distancing Sakartvelo from the path toward European integration. Many of these laws replicate Russian legislation restricting democratic freedoms of Sakartvelo’s citizens. Entire social groups—such as queer communities and professionals in culture, the arts, and academia working in close international cooperation within the non-profit sector and supported by Western and European funding—have been marginalized. Many Kartvelians were outraged and actively opposed the country’s official political course.

Almost a year has passed since the protests began.

Several hundred people continued to gather every day in Tbilisi to protest.We see that the movement still lacks recognizable leadership—neither former president Salome Zurabishvili nor the official opposition stands behind it. No formal coalitions or coherent political programs have emerged. People near the parliament organized themselves: they lit bonfires, celebrated New Year’s and Christmas, stormed the parliament, built barricades, and assisted those injured by special forces.

Georgian Dream continues to employ severe force against protesters as well as potential opinion leaders, carrying out attacks on party offices and individual politicians who oppose the regime. Protests are brutally suppressed with the use of tear gas and water cannons in near-freezing temperatures. Among the crowds, provocateurs acted violently, attacking individual participants. Security forces, armed and organized following Russian models, operate anonymously and with impunity.A disproportionate system of fines for participation in demonstrations has been introduced, alongside widespread video surveillance and tracking programs modeled after Russian protocols. Mobile networks are jammed during protests. Nevertheless, some civil servants have resigned and joined the protesters. High-ranking officials from security agencies, as well as engineers and operators directly involved in suppression—such as water cannon operators and firefighters—have also stepped down.

On October 4, protesters stormed the presidential palace in Tbilisi. The organizer of the rally, opera singer Pacha Burchuladze, was detained; special forces dispersed the protesters, and the following day all those involved in organizing the demonstration were arrested. Georgian Dream celebrated victory.

On October 7, 2025, the European Parliament approved legislation simplifying the suspension of the EU visa-free regime for countries posing security risks or violating human rights—a measure that will undoubtedly soon affect Sakartvelo.

From the platforms of Georgian Dream, pro-Russian narratives are being promoted—alongside disinformation about the situation in the country, fear-mongering about a possible war with Russia, and openly anti-Western rhetoric. All of this is polished with meaningless populist slogans such as “With Peace to Europe,” the cultivation of “traditional values,” and the deliberate silence about the real situation along the Russian borders. The country continues to drift toward a Belarus-style scenario.

RUSSIAN MILITARY BASES IN OCCUPIED TERRITORIES:

Meanwhile, as twenty percent of its territory remains under Russian occupation, the Georgian government avoids publicizing the regular kidnappings and torture of Sakartvelo’s citizens along the border. It also conceals the growing Russian military infrastructure on the territories under occupation. Georgian Dream does not report on these issues; on the contrary, it continues to deepen the country’s economic and logistical dependence, further binding Sakartvelo to the economy of the occupying state.

Infrastructure Statistics:

Over the past sixteen years, Russia has built all the infrastructure it needs for active military operations: roads, trenches, and bunkers.

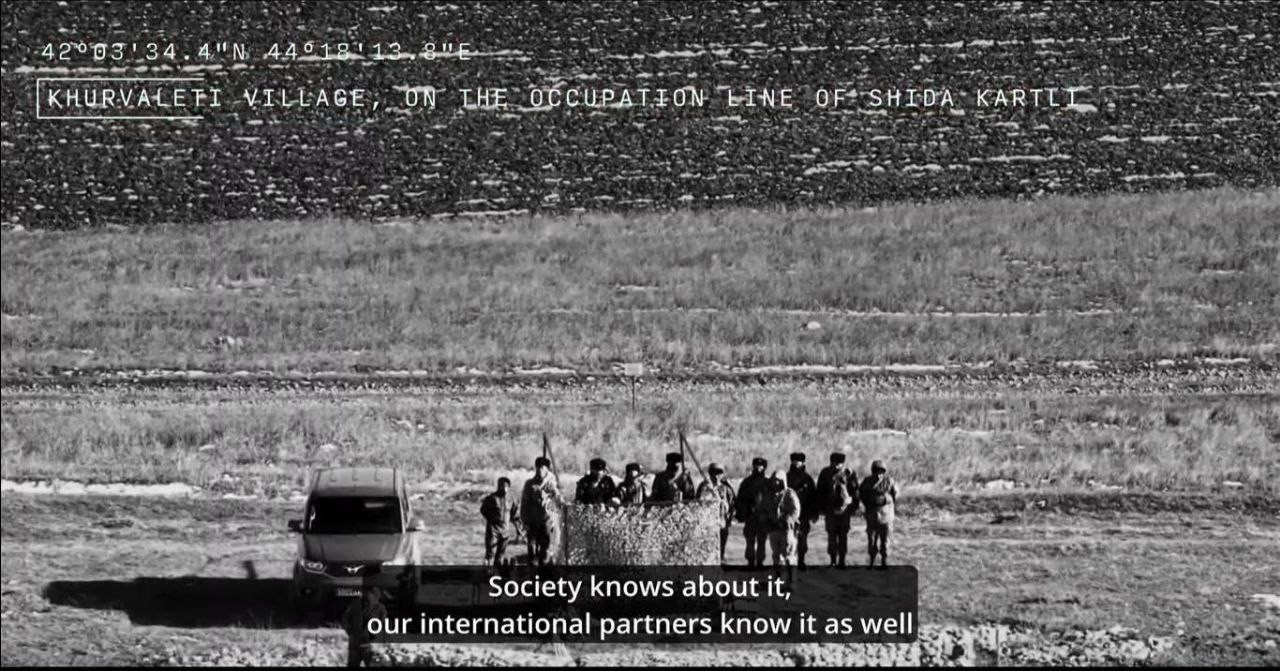

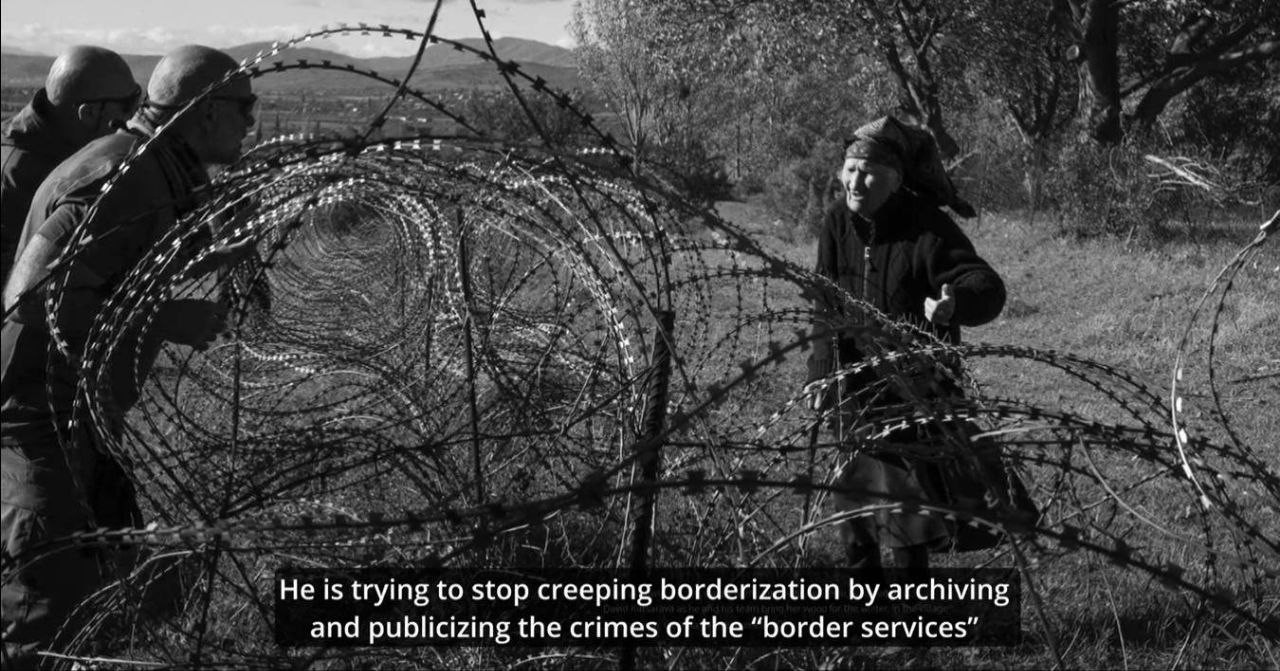

The process of constructing military infrastructure continues and has intensified again since 2023. We can observe this military choreography along the occupation line through video reports by the movement “Strength in Unity” (website in progress, videos available on Facebook).

Since 2009, large modern military bases have been actively constructed on the occupied territories. A new mountain road has been laid for military equipment, bypassing the gorge.

The occupation line in Shida Kartli stretches 418 km. Seventy kilometers are reinforced with barriers. The remaining sections are used as tools of pressure—the barbed wire and observation posts are constantly moved 100–150 meters deeper into the territories controlled by Sakartvelo. This process has been termed “borderization.” The issue, unquestionably, is not merely territorial, but rather a demonstration of power and authority—a creeping occupation.

There are more than seventy Russian military bases and observation points on the occupied territories of Abkhazeti and Shida Kartli (72, according to 2024 patrol reports from the anti-occupation movement “Strength in Unity”).

The largest and best-organized military base is located in Tskhinvali (42.23619904930315, 43.95784125725989), just two hours’ drive from Tbilisi. It houses forty units of heavy equipment and around 800 personnel.

Another major base is in Gali, controlling the main road leading to the largest Georgian settlement in Abkhazeti, home to about 40,000 residents (42.62602, 41.73490).

Before the full-scale war in Ukraine, the personnel of the military bases was estimated at around 10,000.

Now, that number has decreased by about half. Active construction is underway in Ochamchire, where a naval base is being developed. In 2024, a Russian missile carrier entered the port there for the first time. It is evident that this port will be used to receive Russian warships.

In the area of Tskhinvali—seemingly not a strategic priority for Russia at present—a Murmansk electronic intelligence and warfare system (RER/REB) has been deployed.

The Murmansk-BN electronic warfare complex is a shortwave coastal system designed for radio reconnaissance, interception, and jamming of signals across the entire shortwave range at distances of up to 5,000 km. It is primarily capable of “deafening” and “blinding” enemy intelligence assets and the sensors of “smart” weapons.The system is mounted on seven KAMAZ trucks, with its antenna array deployed on four telescopic masts up to 32 meters high. The standard deployment time is 72 hours. There are not many Murmansk-BN systems in existence, and almost all of them are currently stationed in Ukraine, engaged in the ongoing full-scale war.

Regular military drills take place at the bases — explosions and gunfire can be heard, dogs are barking. Along the occupation line, new observation posts are being established, trenches and dugouts are being dug. While this may primarily serve as psychological pressure, in the context of a full-scale war with a neighboring state, these actions naturally provoke serious concern.

Many Russian military bases can easily be located via markings on Google Maps and other sources.

Sakartvelo does not have a regular standing army. The country’s defense capacity is very weak. International military exercises and Western support for the Kartvelian defense industry had played an important role. However, on July 5, 2024, international military exercises were canceled, and funding programs were subsequently closed. The United States indefinitely postponed the start of the NOBLE PARTNER exercises following false accusations by the Georgian government of external pressure, attempts to open a second front against Russia, and alleged coup plots.

Behind the so-called “diplomacy” of Georgian Dream lies a desire not to provoke the “elder brother,” with whom a hybrid war continues. It can hardly be called true diplomacy, as Georgian Dream remains a direct beneficiary of its deals with Russia. Moreover, this paranoid regime rejects the principle of power rotation—an essential condition for the path toward European integration. Bidzina Ivanishvili, who has led the ruling party since 2012, shows no intention of sharing power.

It is also worth acknowledging the speed with which the United States redirected its support programs and expanded its influence. Military and civilian assistance was quickly redirected to the neighboring country, Armenia.

In other words, without Western assistance, the country’s defense capacity—despite the complexity of its terrain—remains very low.

TORTURE AND ABDUCTIONS ALONG THE OCCUPATION LINE

After the 2008 war, 189 villages in Sakartvelo were occupied; now 125 remain on record, as many villages were abandoned after the occupation. The borders are constantly and arbitrarily shifting.

As a result of the war, 408 Georgian citizens were killed, including 170 servicemen, 14 Ministry of Internal Affairs employees, and 224 civilians. The number of wounded and injured reached 2,232, among them 1,045 servicemen.

As a consequence of the war, up to 30,000 people were added to the ranks of refugees, bringing their total number in Georgia to more than 290,000.

If one looks at Google Maps over different periods of time, it becomes clear that military infrastructure has been built in place of residential houses. The occupiers’ goal is to empty the adjacent territories. And judging by satellite imagery, they are succeeding. Regular military exercises and the frequent arbitrariness of soldiers and border guards create moral and physical pressure on the remaining residents.

A well-known case occurred when an elderly man fell asleep in Sakartvelo and woke up on the other side of the barbed wire — in the Russian Federation. The occupation line had been moved while he was asleep.

During Russian military exercises, people living near the occupation line cannot sleep at night: searchlights are turned on, explosions are heard, dogs bark. People become involuntary participants in these events, and many who have previously experienced war suffer from PTSD.

Russia continues to violate all of its obligations under the international ceasefire agreement of August 12, 2008.

The number of refugees continues to grow:

2017 — 247,000 refugees 2024 — 292,000 refugees

The figures are provided by GCRT, a non-governmental organization that offers medical, psychological, and social assistance to people affected by violence, particularly to those who have suffered due to the situation along the occupation line. GCRT also maintains contact with EU monitoring missions (EUMM).

The situation along the occupation line remains dangerous. Over the past 16 years, more than 3,500 people have been abducted, all of them civilians. There are seven known cases of killings during detentions.

In October 2019, official EU observers were also kidnapped by Russian special services.

There are specific dates when arbitrary actions intensify — for example, on Russian patriotic holidays or in August, marking Russia’s attack on Sakartvelo (the August 2008 war). On these days, Russian border guards carry out special provocations against local residents, detaining and beating them on ethnic grounds, while mocking them with derision.

Not everyone can leave their homes. This is especially difficult for the elderly. For families with limited mobility, locals try to organize aid and deliver medicines. Russian forces terrorize them. Families divided by the occupation line also suffer — their homes literally split in two. People are fined for crossing the line and detained. Naturally, family and diaspora ties are disrupted.

What happens to those detained along the occupation line?

Those detained are taken to a Russian base and forced to sign documents under pressure, without being provided translation into Kartuli. After that, they are transferred to a detention center in Tskhinvali. The judicial process and negotiations take place in Ergneti, with representatives from Ossetia, Russia, Sakartvelo, and the EU.

After the trial, detainees are either sent to prison in Tskhinvali or handed over to the Kartvelian side. Volunteer groups record cases of detention and abduction and provide humanitarian and psychological assistance whenever possible.

Meanwhile, those abducted are pressured by local authorities to remain silent and avoid public attention. Civil institutions that structurally supported survivors of torture and abductions were forced to cease operations in 2024 after the adoption of the “foreign agents” law.

Borderization has never stopped, and Russian troops have been moving deeper into the country for all these years. The current government of Sakartvelo remains silent about this.

THE “FOR PEACE” PARTY

Trenches are being dug, torture is silenced, the façades of Rustaveli Avenue are repainted, trucks with dual-use goods speed by, faces smile tensely at receptions with Hamas and Hezbollah, heads explode, and Turkish delight melts in the mouth.

Russia continues its neocolonial pressure on the countries that were once part of the USSR. Small border states find it difficult to resist. Border regions are used as buffer hubs to circumvent sanctions, sell oil, and sustain Russia’s military-industrial complex.

Sakartvelo holds a rather vulnerable position. The country is perfectly suited for the Kremlin’s geopolitical revenge amid structural defeats inflicted by the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Sakartvelo cannot resist like Ukraine — there is neither the manpower nor the resources to fight. People remember previous wars well, and this is why the “For Peace” party enjoys significant success here, even without the influence of Russian political technologists — though their presence is evident.

Before Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, there had already been wars: in Ichkeria (Chechnya) in 1994–1996 and 1999–2009, in Sakartvelo (Georgia) in 1992–1993, the five-day war in 2008, and the war in Ukraine in 2014.

Nearby lies Belarus — a country occupied by the Russian regime. Many Belarusians previously moved to Sakartvelo in search of civil freedoms.

Other neighboring countries also experience constant economic and political pressure. Russia interferes in their local elections, organizes sabotage, and attempts coups (Moldova, Armenia, etc.).

Now that Russia has succeeded in installing a strongly pro-Russian government in Sakartvelo, there is no obvious reason for a direct attack. Instead, it strengthens economic infrastructures beneficial to Russia and extends the necro-lawless field from the territory of Mordor.

Dissenters are imprisoned on fabricated charges, with prohibited substances planted on them. Others are marginalized in different ways: for instance, military journalist Ucha Abashidze, who in 2017 conducted a detailed analysis of Russian military bases and covered cases from the Ukrainian front, was accused of distributing pornography and storing weapons. His trial was held behind closed doors, and both he and his wife, Mariam Iashvili, were imprisoned. He was detained during a witch-hunt campaign when opposition offices were being raided and individual protesters attacked. Georgian Dream and Russian political technologists were preemptively identifying opinion leaders who called people to the streets.

Volunteers of the Georgian Legion, fighting on Ukraine’s side and defending not only Ukraine but also the principles of territorial integrity of independent post-Soviet states, are likewise being marginalized in public discourse. They are called mercenaries “fighting for money,” often denied re-entry to the country, and subjected to political pressure.

One member of the Georgian Legion was recently detained in Armenia at Russia’s request for extradition — Armenia refused. At the same time, there have been several cases of political pressure from Sakartvelo itself against those fighting on Ukraine’s side: many were summoned for interrogations, and some were denied entry to the country.

To subjugate a country, one must create a “For Peace” party, because few people would openly support war.

Georgian Dream skillfully uses the fear of war with Russia to its advantage. On the 17th anniversary of the war, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze accused former President Mikheil Saakashvili and his 2008 government of starting the August war. There is nothing new in this political tactic — it is an ancient and effective method of perception management.

In the name of peace, they will resort to any repressive measures against dissenters. In the name of peace, alternative voices and tactics will be terrorized and marginalized. The task of Georgian Dream is to carry out a communication operation — to polarize and simplify the civil polyphony of protests by labeling protesters as Saakashvili’s supporters.

But it is worth remembering that the protests were started by students — whose political awakening occurred during Georgian Dream’s rule, not as successors of Saakashvili’s government logic.

The protests were initiated by young people analyzing the country’s drift toward becoming a Moscow province, noticing that Russia’s military doctrine has transformed into principles of governance.

Statistical data provided by NGO GCRT and David Katsarava, leader of the anti-occupation movement Strength Is in Unity.