This is a war of extermination and genocide

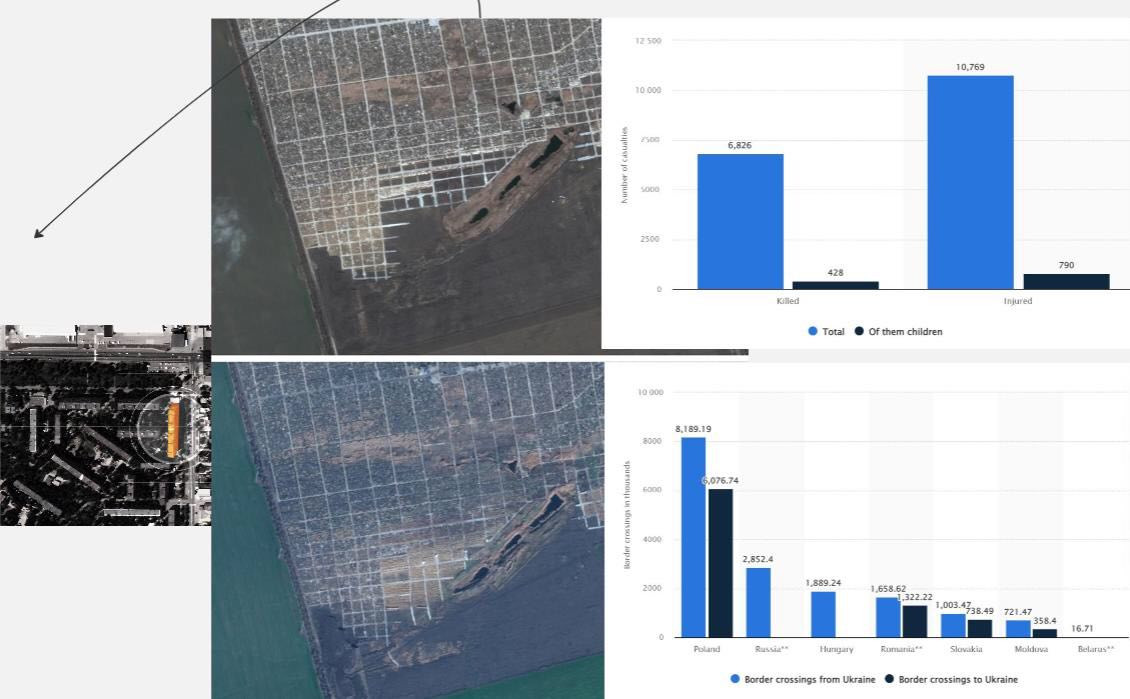

A full year has passed since the start of Russia’s new full-scale invasion of Ukraine.More than ten million people have become refugees and asylum seekers, tens of thousands have died and entire cities have been razed to the ground by the Russian army. Genocide is being systematically carried out in the Russian-occupied territories. Ukrainians are sent to filtration camps and forcibly deported to remote regions of the Russian Federation.

Russia daily strikes civilian objects, homes, and public places away from the front lines to demoralize and intimidate the population of Ukraine.

Why does Russia need this war ?

The political regime in Russia : resentment, expansion, and militarism as foundations of ideology.

It is almost impossible to explain the full-scale military invasion of Ukraine on 24.02.02 and the outbreak of war in 2014 within the framework of economic logic.

Even without taking sanctions into account, the military action and occupation of Ukraine’s territories only bring serious losses to Russia. The invasion could potentially weaken Russia economically to the point of questioning the very existence of the state.

The conspiracy theories about “preventing NATO expansion to the East” do not stand up to scrutiny. The outbreak of war in 2014 only brought NATO countries together and in 2022 led to Sweden and Finland joining NATO, directly bordering Russia.

The reason for the invasion is political and ideological.

After the turbulent nineties and experiments of the early 2000s, the state ideological apparatus and the whole Russian political culture have crystallised around several ideas: the accumulation of power in one centre, expansion, the exclusivity or chosenness of Russians, revanchism, and ressentiment.

These ideas are not new. On the contrary, they have permeated Russian culture since its inception, allowing to rely on them as on traditional ones. For simplicity, let us refer to this set of ideas as the Russian imperial project. It can be argued whether and to what extent there are elements of opposition to these ideas in Russian culture.

At the moment there is no elaborated, articulated, and visible alternative to the imperial project in Russia.

Russian leaders have traditionally used war as an instrument of domestic politics. Yeltsin tried to boost his ratings and consolidate his hold on power after defeating parliament and changing the 1993 constitution by starting the First Chechen War. Putin came to power by betting on militarist mobilisation and the start of the Second Chechen War. The Second Chechen War was also interpret in revanchist terms — as a return to greatness, albeit in very small steps. After a series of political and economic problems, it was the annexation of Crimea and the war with Ukraine in 2014 that managed to unite Russian society around Putin’s regime.

Ukraine, a former colony of Russia, is not only fighting for political independence but also making visible the possibility of alternative political projects and a radically different political culture in spaces that were once part of the empire. By its very existence and any successes, it questions the necessity and hence the legitimacy of the Russian project, which is inconceivable outside the imperial framework.

The Russian state and its actors have constantly talked about the artificial nature of Ukrainian identity and the need to strip Ukrainians of their political subjectivity. The genocide that is taking place is a logical and material embodiment of this set of ideas.

This is not the first genocide in Russian history and, if Russia is not stopped, it is unlikely to be the last.

Russia is war. As long as the state of Russia exists, it will be at war or preparing for a new war.

What role does Russia play in the region?

Russia is holding back any positive change in the region. The less influence it has, the more hope there is for emancipatory change.

Not only the Russian Federation tries to make as many regions and countries as possible economically dependent on it, but also consistently maintains a political culture that is complimentary to its own: patriarchal attitudes, misogyny, homophobia, nationalism of the “state-forming” nation, and autocracy.

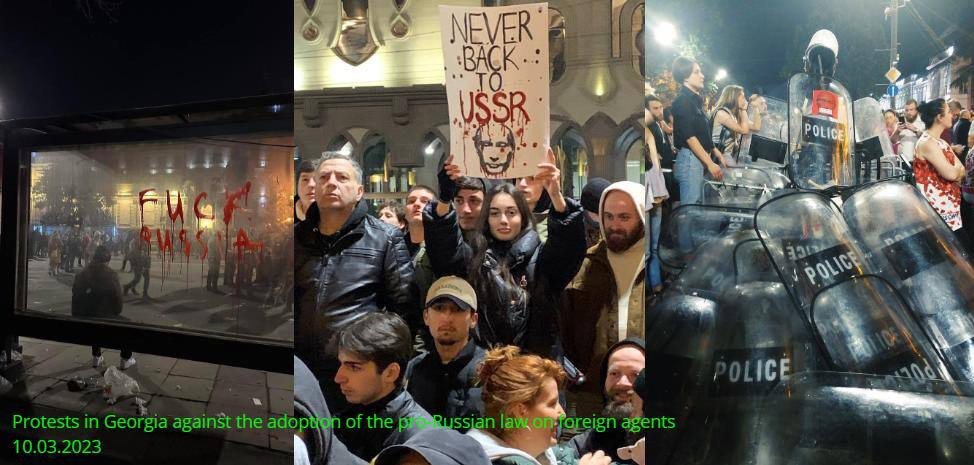

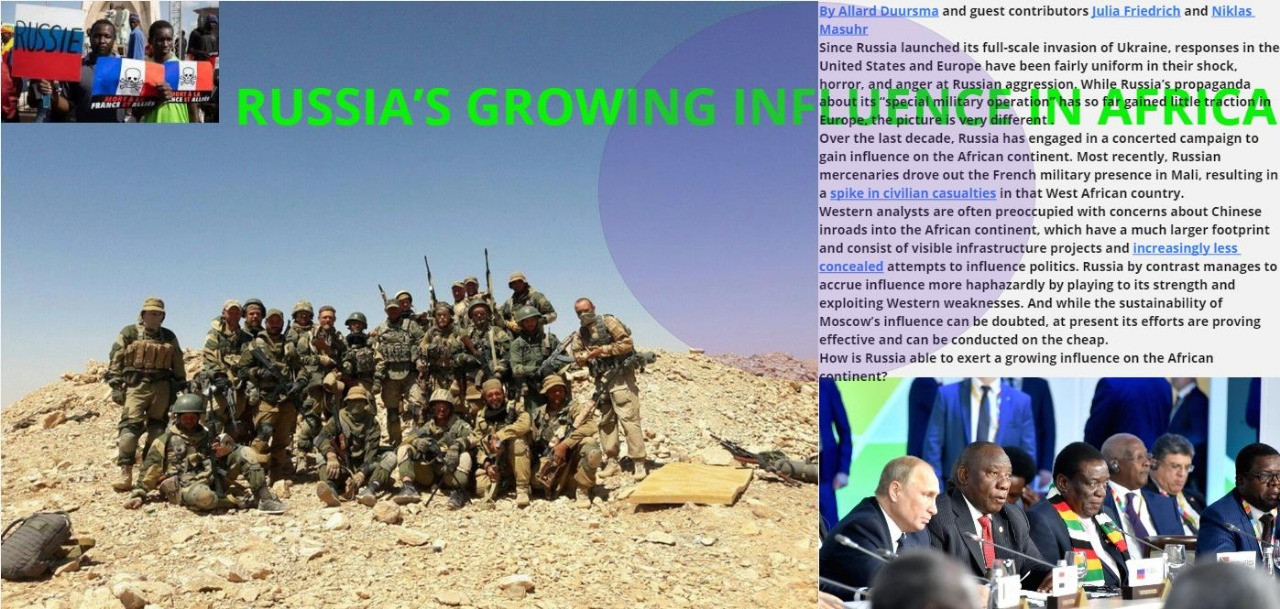

The Russian state structures and businesses are supporting far-right and often pro-Russian movements and regimes not only in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe but also worldwide. The Russian army is involved in the bloody suppression of protests in neighbouring countries. Once again, as it was in the 19th century, Russia is acting as “gendarme of Europe”, but now with much less capacity.

Russia is moving steadily to the right and militarising everything it touches. Russia is blocking any positive change in the region from happening. The less influence it has, the more hope there is for emancipatory change.

What opportunities does the Russian Federation have?

The Russian Federation is an economically weak and dependent state

Today, Russia is capable of making some breakthroughs in certain areas of economy, but it is incapable of maintaining the results and developing them without any direct foreign assistance. Even the extractive industry is critically dependent on Western technology and equipment.

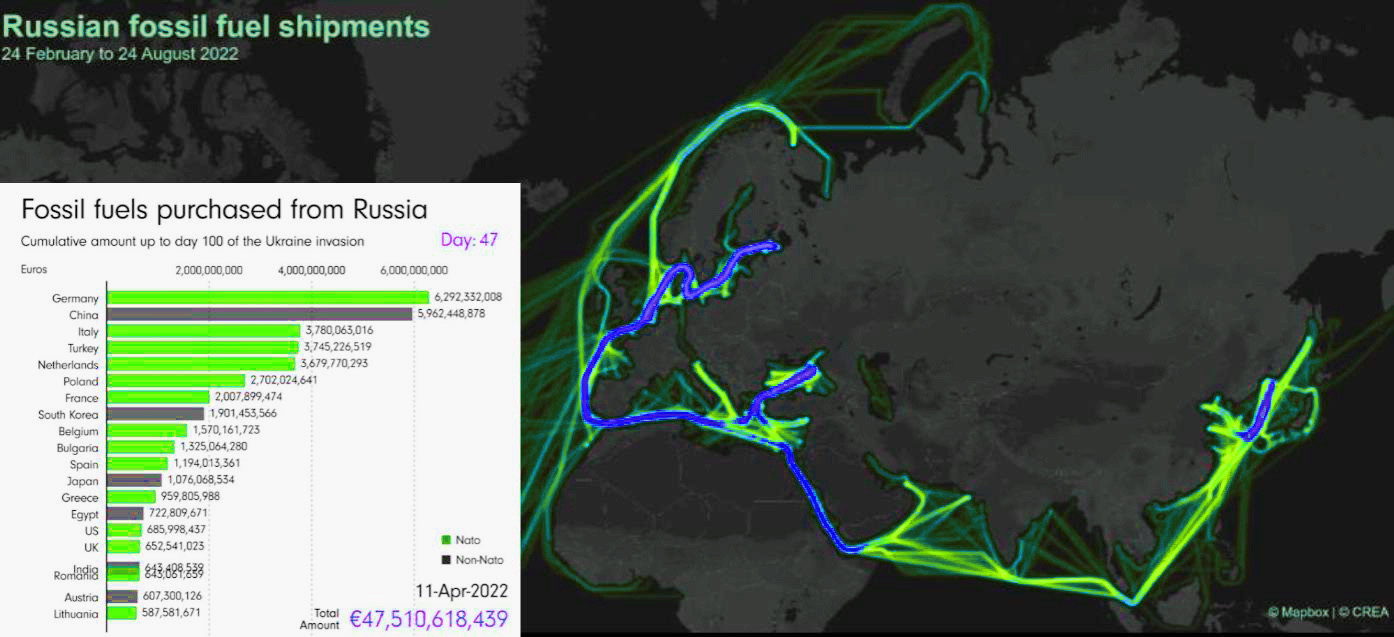

Hydrocarbons completely dominate the structure of exports and foreign exchange earnings.

Western European countries have been the main importers of Russian energy resources since the early 1980s. The main means of supply are gas and oil pipelines. The biggest importers of Russian oil and gas have not given up on them and are in fact in a state of dependence, which they have begun to address urgently. Last year Russia supplied the EU with 40 percent of its natural gas, with Germany being the largest importer, followed by Italy and the Netherlands.

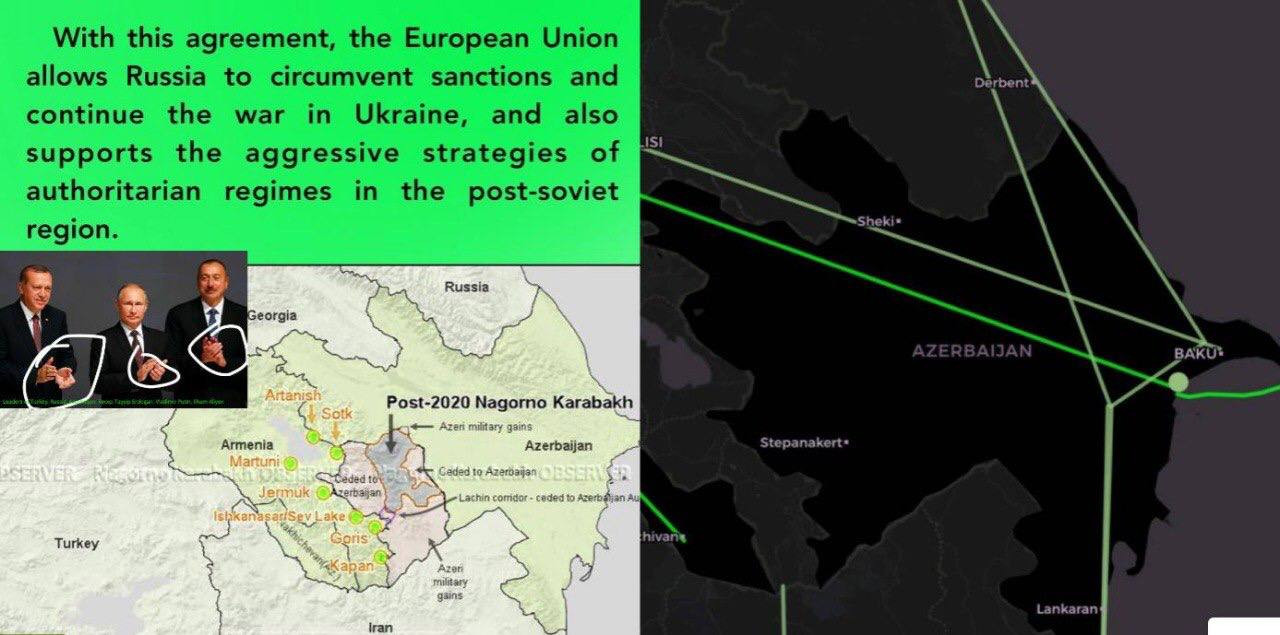

Officially, EU states are increasingly seeking to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) by tanker from producers such as the US and Qatar, but in reality Russian gas is returning to Europe with the involvement of Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Russian gas is returning to Europe with the involvement of Azerbaijan and Turkey.

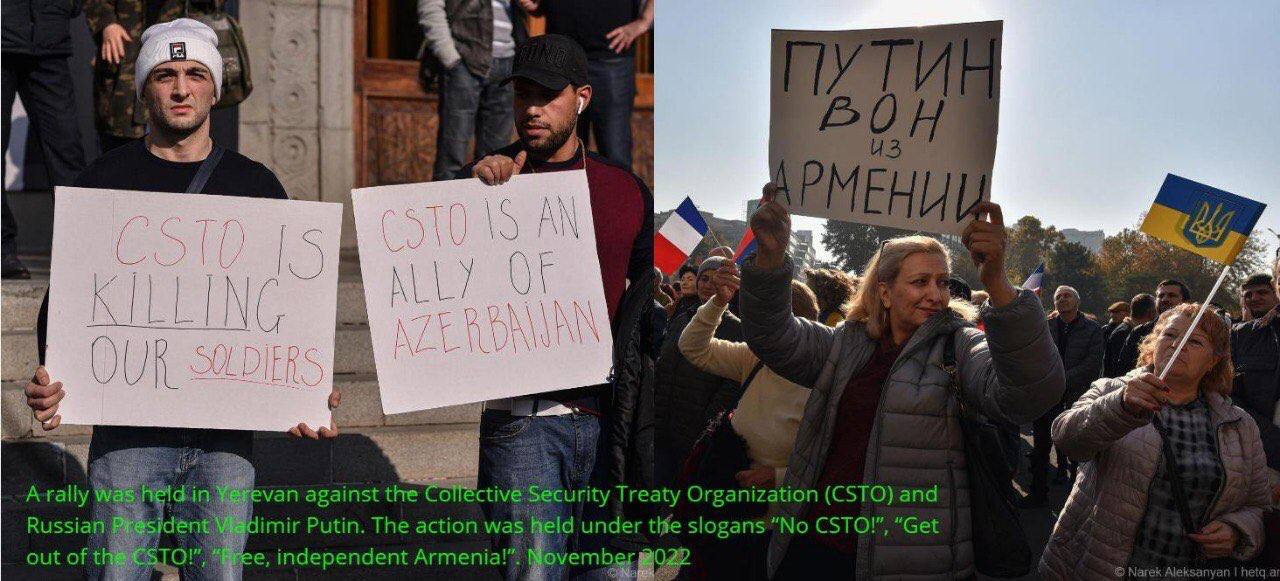

The European Commission has signed a memorandum with Azerbaijan to double Azerbaijani natural gas imports up to at least 20 billion cubic metres per year by 2027. To circumvent its own sanctions, the EU makes an agreement with another authoritarian regime that violates human rights in its own country and attacks its neighbour, Armenia.

But where in fact this gas is really going to come from?

The crucial infrastructure needed to extract and transport gas from the Caspian Sea to Europe is jointly owned by Lukoil, a Russian oil and gas giant with close ties to the Putin regime. Lukoil is one of the top three taxpayers in Russia. In 2019 it contributed more than $200 billion in taxes alone. Lukoil is also among the companies on the US sanctions list.

The company has been operating in Azerbaijan’s oil and gas sector since 1994. In the early 2000s, it focused its efforts in Azerbaijan on developing the Shah Deniz fossil gas fields, which are among the largest in the world.

In fact, days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Lukoil completed a deal to acquire Malaysia’s Petronas stake in Shahdeniz for $1.45 billion, increasing its stake in the project from 10 to 19.99 per cent and becoming the second largest shareholder after British Petroleum (BP).

And that is not all.

Russian energy giant Gazprom has started supplying natural gas to Azerbaijan under a new contract the company has just announced. In a statement, Gazprom said it has signed a new agreement between SOCAR and Gazprom to supply natural gas to Azerbaijan.

The deliveries under the terms of the agreement started on November 15 and will last until March 2023. The total volume will be up to 1 billion cubic metres of gas until March next year.

In this way, the European Union allows Russia to avoid the sanctions and continue the war in Ukraine and supports the aggressive strategies of authoritarian regimes in the post-Soviet space and the Middle East.

After the explosions in the Baltic Sea to compensate for the damage and to divert supplies from the two Nord Stream pipelines after the explosions in the Baltic Sea, Putin persuaded Erdogan to pump more Russian gas through Turkey

Ankara and Moscow agreed in September to start paying for natural gas supplies in rubles.

On 29 September, Putin and Erdogan hold talks on a possible expansion of Moscow’s sales of military defence systems to Ankara, despite US objections.

On 20 November, Erdoğan ordered the “Sword Claw” operation in Iraq and Syria and began bombing the PKK.

European countries accounted for more than half of all Russian crude exports in 2021.

EU countries stopped imports of Russian crude delivered by sea, with a ban on petroleum products from February 2023. The United States also stopped all imports of Russian oil. The UK has pledged to completely stop importing Russian oil by the end of this year.

However, a number of countries are still heavily dependent on the Russian Federation. The data for September 2022 show Slovakia and Hungary at the top of the list.

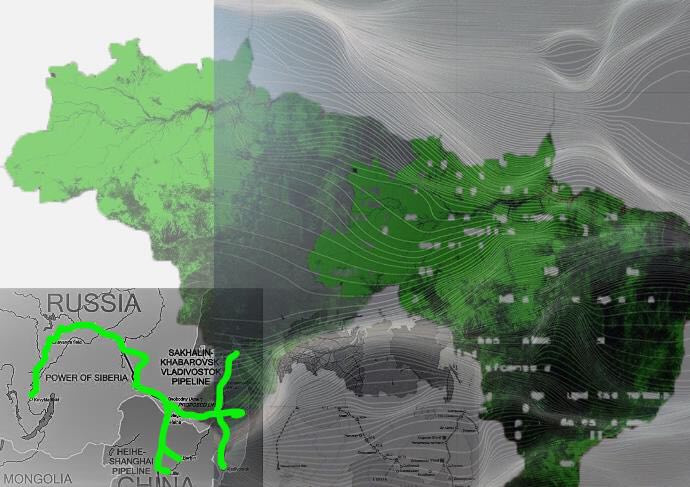

India and China have now become the biggest buyers of Russian oil at a heavily discounted price (in mid-December the discount for Urals oil was just under $30 a barrel). Other countries have also taken advantage of the discount on Russian oil — for example, Sri Lanka, which is experiencing a serious economic crisis. Pakistan is also engaged in negotiations with Russia to buy oil at a discount, although a deal has not yet been struck.

In order to redirect exports to Asian countries, infrastructure — at least pipelines and an entire merchant fleet — needs to be built. To that end, the Amur gas processing plant is being built and the Kovykta field in the Irkutsk region, a new section of the Kovykta-Chayanda section of the Power of Siberia pipeline, is being launched. The gas route will be over 3,000 kilometres long, with a planned design capacity of 27 billion cubic metres of gas per year. Here, one can examine the annual capacity of Russia’s natural gas export pipelines of 2021.

Under the most favourable conditions, this will take years to complete. Cheaper oil encourages flow to Asia, but rerouting oil from the EU would be more expensive, time-consuming, and burdensome for Russia.

Up to autumn 2022, because gas prices were at record highs, Russia continued to receive ample foreign exchange revenues. The car industry has already completely shut down, while other industries are running on previously accumulated stocks, which will not last long. Russia has so far managed to avoid an economic collapse due to sanctions and the withdrawal of major producers from the market, but if the sanctions and boycott continue, it will not be for long.

Although the price of Russian crude is attractive, Indian refineries have faced a problem in financing purchases as sanctions on Russian banks have affected payment transactions.

One option considered by India was a system based on local currencies, whereby Indian exporters would be paid in roubles instead of US dollars or euros and imports are paid in rupees. Nothing has come of that.

China’s state-owned oil enterprises, however, are increasingly using the renminbi rather than the dollar to finance their oil purchases.

Meanwhile, no sanctions have been imposed in the field of nuclear energy, where Russia is the largest global player. Kasper Schuletsky and Indra Overland of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs published an analysis of what is happening in this area in the scientific journal Nature Energy.

“Rosatom” is the leading supplier in the nuclear energy market, controlling 38% of global uranium production and 46% of uranium enrichment capacity. Russia’s main competitors in nuclear power are China, France, Japan, South Korea, and the United States, which together account for about 40% of the market. Since the invasion, Czech energy company CEZ has signed contracts with the U.S. Westinghouse Electric Company and France’s Framatome to supply nuclear fuel, and Finnish energy company Fortum cancelled its nuclear reactor project with Rosatom and hired Westinghouse to develop, license and supply a new type of fuel for its Loviisa plant. Bulgaria, Poland, Spain, Slovakia and Hungary have also entered into similar agreements, but many agreements with Rosatom are still in place.

Despite its enormous size and abundance of available natural resources, Russia is unable to stay afloat for any length of time without economic ties to Western countries.

MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

Russian Military Potential, Military Losses and Recoveries

The Russian military-industrial complex is the direct heir to the Soviet one. Over the last 30 years, very few new weapons have been put into mass production. The Russian military-industrial complex is mostly engaged in repairing, supporting, and upgrading what has been produced during the Soviet era.

The production capacity of the military-industrial complex is extremely low.

The Russian military-industrial complex is critically dependent on supplies from the West. Even if one were to imagine China suddenly changing its policy, it is either difficult or impossible to replace the supplies with counterparts. It could take years for the same machines and production lines to be replaced. One way or another, they will have to find ways to circumvent sanctions.

Even a military mobilisation of the economy would require a reorganisation of supply chains and maintenance and components for Western machinery. Modernisation without imported, i.e. Western, components is also impossible in most cases.

Corruption in Russia is rampant in all sectors, but the military industry is obviously one of the most corrupt. Unlike the United States, Russia has no extensive network of contractors for the military-industrial complex. Orders are not distributed transparently within large holdings and corporations. Control over order fulfillment is also buried deep in the guts of an unwieldy and nontransparent machine. It is a perfect environment for drawing the wool over the eyes of superiors and slashing budgets. Last spring, there were even rumours that the generals who had stolen the military arsenals were interested in the warfare.

Despite the fact that the Russian Federation is at the top of the list of arms dealers on the world market, the Russian military-industrial complex is unprofitable and constantly requires huge infusions of money.

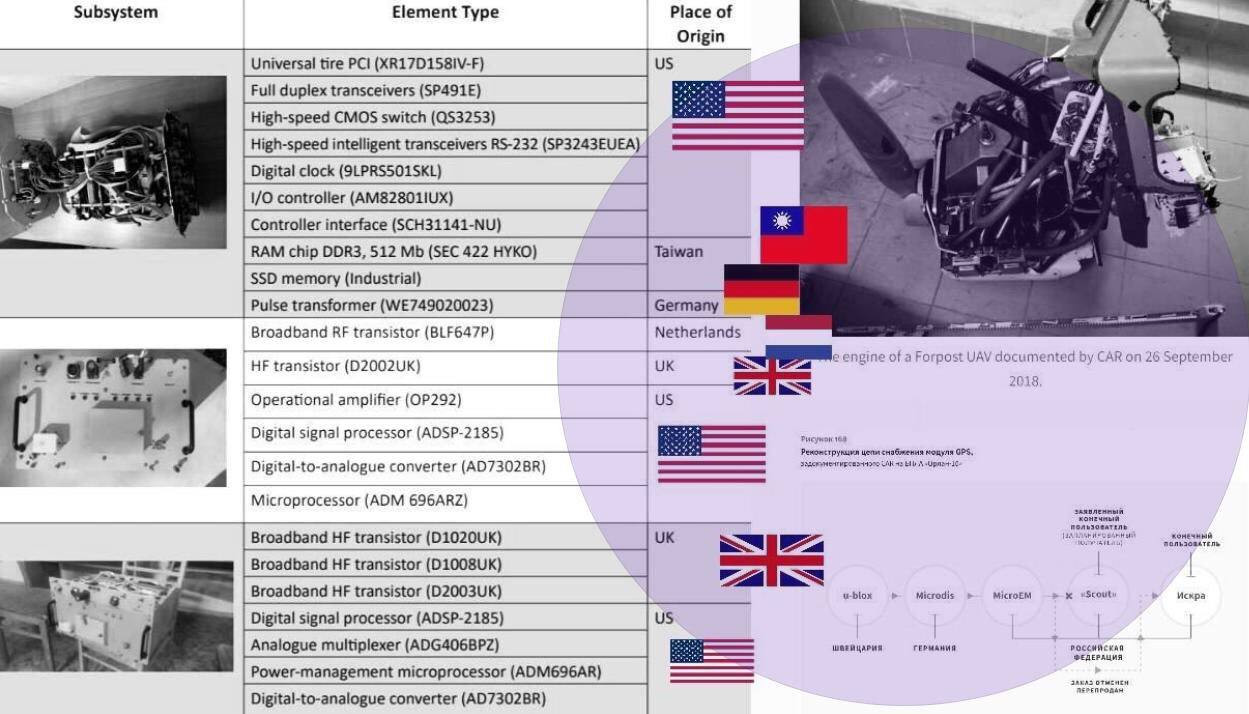

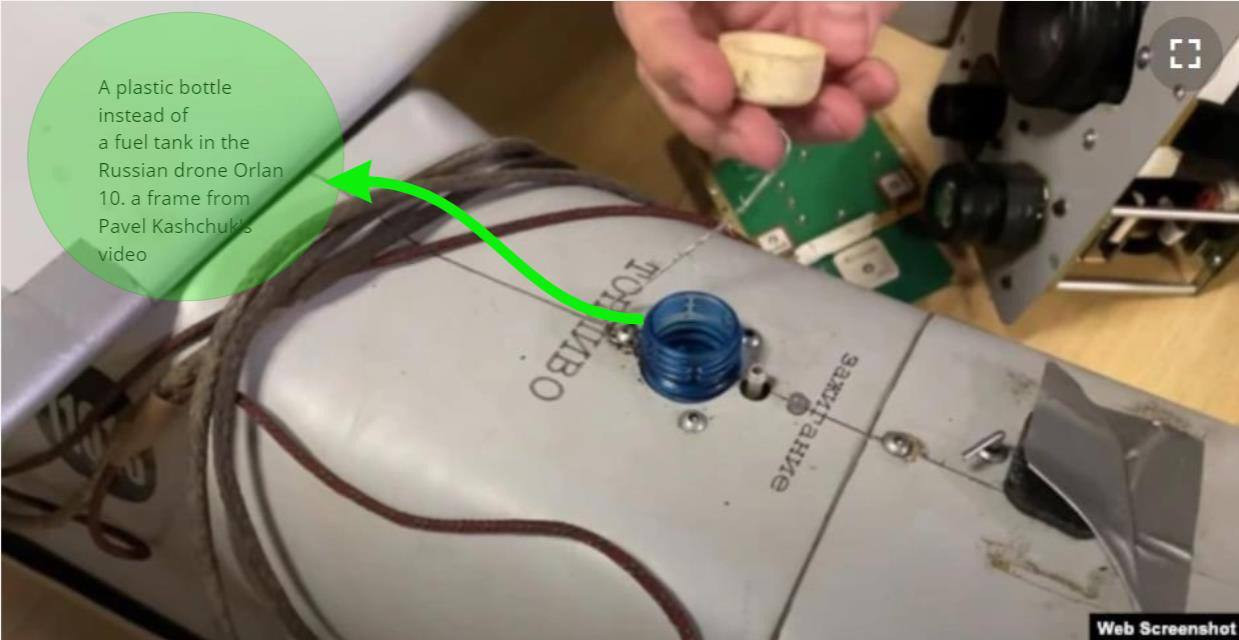

However, the Russian military-industrial complex is practically incapable of producing any significant quantities of modern weapons and components at all. This is especially true for UAVs, secure communications, microelectronics, and self-produced guided weapons.

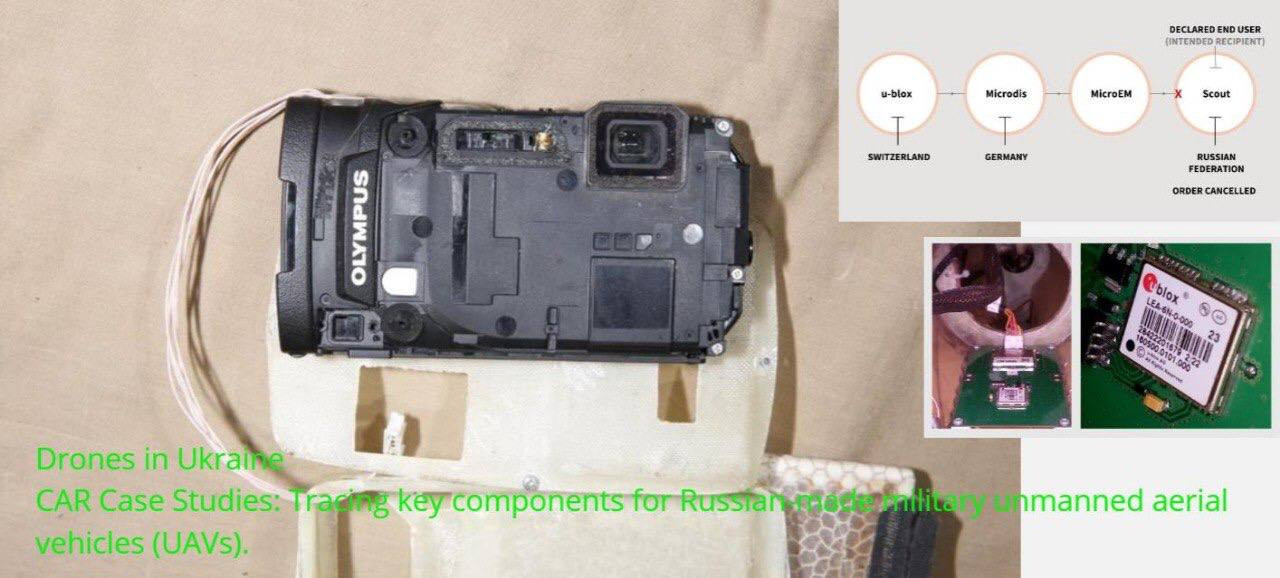

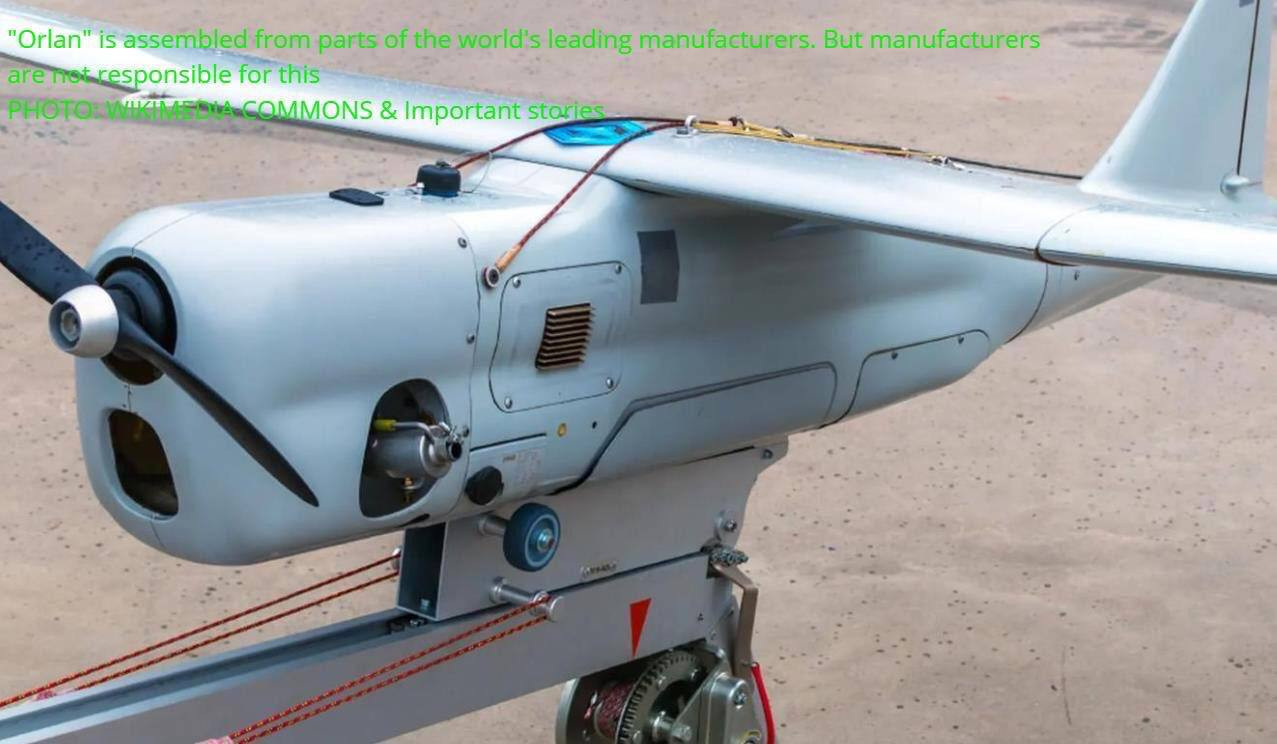

The well-known Moscow-based Orlan 10 drone, for example, relies on a complex supply chain that extends far beyond Russia.

A recent investigation by the Russian media, Reuters and iStories in cooperation with the British Institute of Defence Studies, revealed a logistics trail that spans the globe and ends at the Orlan production line, at the Special Technology Centre in St Petersburg, Russia.

Financial records, customs data, court records, Russian company documents, and several other public sources indicate that many of these imported Western-made items are likely purchased by SMT-iLogic3 on behalf of STC4, based in St. Petersburg, which was first sanctioned by the US government in December 2016 for supporting Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

STC LLC or STC — (the Russian military manufacturer of the Orlan-10 UAV1 drone) — has dramatically increased imports of critical Western-made components since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

According to RUSI, the Eagle uses components from US-based Altera and Xilinx, Texas Instruments, Microchip Technology, Analog Devices, Linear Technology, European STMicroelectronics and NXP Semiconductors, Japanese Renesas Electronics, and Saito Seisakusho.

At present, there is a reason to believe that the Russian military-industrial complex can continue to operate for some time, considering the resources accumulated in its stockpiles. But given the nature of the hostilities and the outrageous confirmed losses of equipment, this cannot last for long.

RF Armed Forces

During the last decades, the Russian Army has engaged in direct combat only with small, poorly armed and/or unprofessional opponents. Its “military potential” for a clash with an army similar to Ukraine’s has been assessed on the basis of data that is difficult to verify and assess. Only the facts of massacres of civilians and a general disregard for any humanitarian law could be easily assessed.

The troops of the Russian Federation still using a rampart tactic, which means huge numbers of casualties and destruction. The Russian Armed Forces simply do not have enough high-precision weapons and trained fighters to carry out complex operations. They will commit war crimes not only to intimidate Ukrainians but also because they simply do not know how to fight differently.

In the Russian Federation there is mobilisation, mercenaries from PMCs are playing an increasing role, and in the occupied territories of Ukraine, everyone is being forcibly mobilised into the ranks of the so-called militia. Mobilisation in Russian prisons is actively under way.

As of December 2022, the Wagner PMC represented by Prigozhin is ready to recruit women from the colonies, explaining this by taking over the experience of World War II.

Even those who have gone to fight out of convictions are protesting against the atrocious conditions and the lack of weapons and training for the personnel, to the point of threatening to revolt. There are also cases of desertion.

Are there any forces in Russia which could stop the war?

Internal impulses. The opposition, the regions, the capital, and the nomenklatura.

At the moment the non-systematic opposition are made up of real or potential revanchists. They are more concerned about the struggle for power than with anti-war activities.

All levels of politics were closed for people who were likely to gain followers and potentially take over their bosses through intrigues or more interesting means, like protests. Up to bottom loyalty and inertness were rewarded, which rarely combines with competence and risk-taking required even for the shabbiest of coups.

Parliamentary parties are not independent political forces. Their role is purely decorative. A developed, independent union movement does not exist in Russia.

Consumption level, depolitization and public consensus in Russia

It was not just the state-controlled media-holdings and cultural institutions who supported the state consensus of ‘return to greatness & power’, but oppositional forces too. Greatness & power could mean different things, but always implied expansion. Nationwide exaltation of 2014 finalised marginalisation of those few who spoke against it.

Liberals did not reject the idea of war altogether, just argued it was ineffective while posing risks of “development setback” and “falling out with civilised world”. They preferred the idea of “soft force” and economic expansion.

Organised authoritarian leftists never fully distanced themselves from the right-wing and especially the imperialism. For the most part, even when they did not explicitly support the idea of Russian world expansion, they would still push the idea of ‘Russian world is better than NATO’.

No distinguished or influential opposition members are willing to abandon the idea of a ‘great Russia’ or the Russian project in general. The most well-known of them, Navalny first gained prominence in the far-right wing, and has never rejected his imperial ambitions publicly. Even though some actors are willing to soften and reduce the imperial tendencies, ideas of demilitarisation and federalisation are not wildly popular.

Several groups of Russian opposition expats create “representative offices” in immigration to lobby the interests of ‘good Russians’, to formalise their claims to power and to become dominant attractors of symbolic and financial resources. Yet this ‘opposition’ does not represent anyone but themselves.

State officials/official politicians and security forces/military

The entire political system of the RF is subordinated to putin and his close circle.

‘Official’ politicians and government officials could have tried to gain more power. But since elections of all levels were de-facto cancelled, only a few professional politicians remain. Military is not considered a part of the elite in Russia, lacking both authority and experience in politics. Their status is much lower than that of state officials.

Similarly to the military, security forces (fsb first of all) do not seem to be interested in overthrowing putin on whom their privileged position depends. There is no reason to expect them to stop the war.

Degree of independence of large capital in rf, likelihood of anti-war actions by the capitalists

Evidently, in the RF one can only keep and grow capital while being loyal to the vertical of power. Important assets were (partly) nationalised, turning into state enterprises (russian railways, inter rao, gazprom, rosatom, russian mail), in a way, large capitalists can be seen as managers rather than owners. Business of any level can be forced to be sold to another owner, and disloyal capitalists risk to lose both money and freedom. Interest groups all depend on moscow, devoid of any power.

Something extraordinary must happen for economic powers from within the system to stop the war. At the moment chances this happens are slim.

Society, media and sanctions

Putin rose to power during economic crisis, amid people with very low expectations regarding both economy and politics.

Economic upturn provided by growing fossil fuel prices allowed his regime to exploit rhetorics of ‘stability’ and ‘return to greatness’.

‘Economic stability’ thus became a part of the public consensus too. Political liberalisation was associated with economical and political instability (hence propaganda ‘threatening’ “Do you want it to be like in Ukraine?”). This association must be decoupled, and reassembled the other way around.

Militarism and revanchism in Russia penetrates all pores of society and defines a repertoire of acceptable behaviour.

After 2014, culture production sphere and political groups faced various intergroup conflicts regarding the war against Ukraine, but its questions lost importance soon only to fade to background for the majority of activists. No purposeful critical study of the ‘Russian project’, nor distancing from apologists of the latter happened.

There are enough reasons to think that without economic problems and other threats to habitual comforts, the war could remain completely unnoticed, like the war against Syria was.

After 24.2 russian society carries on its ‘normal life’. Only a serious economic disaster, or a loss of a sense of security would make Russians realise the war is on. Even the wide mobilisation did only shatter but not break the sense of normality.

Anti-war protest, can we hope?

There are anti-war protests in Russia, but only a few sabotage the war machine directly. Most anti-war activities are symbolic and unfold in the media.

After 24.02.02 there was a number of anti-war protests across the country. They were few in number and vastly disorganised. While in the occupied regions of Ukraine people stopped tanks with their bare hands, in Russia activists came out with placards and did not resist when they were immediately detained.

It soon became clear that small-scale street protests were ineffective, and that they quickly fizzled out. The more inert part of society normalised the attack on the neighbouring country. Activists, the opposition, and many who remained in the Russian Federation were demoralised, while some turned their attention to guerrilla tactics.

The situation began to change in September, following the announcement of mobilisation. Residents of Chechnya, Dagestan, and the Republic of Sakha-Yakutia actively resisted and took to the streets to directly confront the security forces. Also, manifestations resumed in the central cities of the Russian Federation, though again poorly organised and easily suppressed by the police.

Since the start of the invasion, there appeared internal and external initiatives that engage in humanitarian activities and the organisation of logistics for people forcibly removed from Ukraine to Russian territory.

These initiatives are almost invisible, operating non-publicly under threat of prosecution by the Russian government. But in some cases they are well organised and effective.

Internal and external humanitarian projects certainly support Ukrainian society and indirectly influence the ability to fight the Russian invasion.

Some groups continue their human rights work by supporting anti-war activists, political prisoners and activists who directly sabotage the war machine, including through direct action (arson, mines).

Feminist human rights coalitions have been formed to help all those who want to avoid mobilisation, including conscripts who have been forcibly sent to war, deserters, and those who have broken their military contracts.

There are individual and collective symbolic actions in the country, the impact of which on the overall situation is difficult to assess. These actions make it clear that the war does not have the unconditional support of the entire population, but it is not clear how this knowledge can affect the situation here and now.

Arson attacks on military committees, which have become more frequent since the announcement of the mobilisation, have been happening here and there around Russia.

Some groups and possibly individuals are engaged in direct sabotage of infrastructure. They strike at the most important and at the same time unprotected part of military infrastructure — logistics. The vast majority of cargo in the Russian Federation is transported by rail. It is relatively easy to disrupt the work of the railroad network, and the effectiveness of such sabotage actions, concerning the risks of detention, is much higher than participation in public protests. While the number of such actions is growing, they have not yet become a serious obstacle to supplying the army.

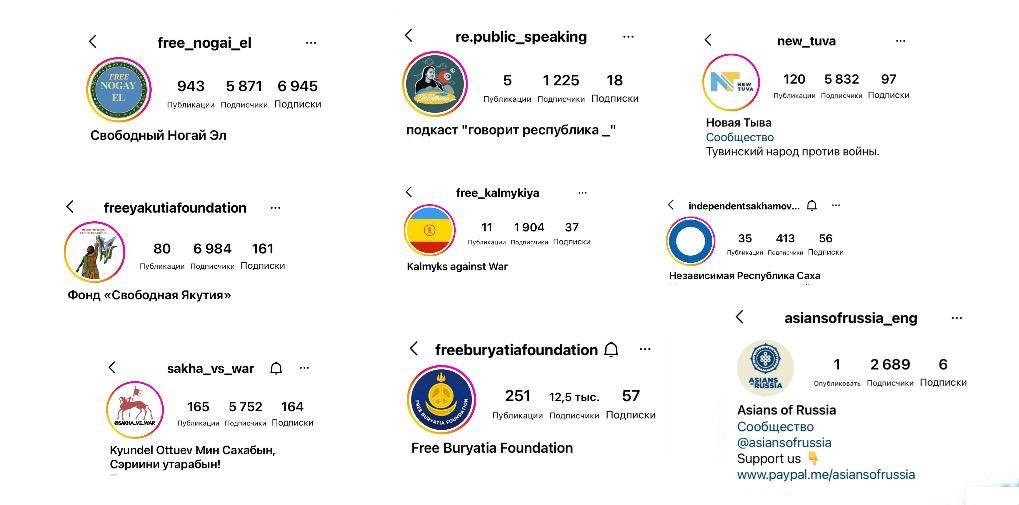

Regionalism, the decolonial movement and separatist moods.

There is a growing reflection on regionalism, national politics, ethnicity, racism, and forced Russification in the Russian Federation.

A variety of ethnic and regional anti-war initiatives that cannot be inherently complimentary to the Russian imperial project are already emerging.

Many indigenous people have issued anti-war statements distancing themselves from the Russian imperial position.

Open data shows that a disproportionate number of indigenous and non-Russian people are being sent to the front and die under Russian rule. Mobilization has taken on the character of ethnic cleansing, which continues the tradition of a racist and cynical approach to the “human resource” of the colonized territories. There is also reason to believe that with the help of mobilisation the Russian authorities have begun to “solve issues” with troublesome ethnic groups whose loyalty is in doubt, as is the case with the Crimean Tatars.

The “inconsistency” of the idea of dying for the “Russian world” in a seemingly multi-ethnic country has become more apparent than ever.

Whatever forms Russian statehood takes, one can trace the continuity of its colonial policy through silencing and erasing the memory of the occupation, enslavement, forced Christianisation, Stalinist repression, and deportations. The use of different ethnic groups as a resource in the wars of the metropolis for new lands is being protested by activists who call for not supporting this policy and appeal to historical parallels: once conquered and repressed lands and peoples should not become accomplices to new conquests.

The Free Nationss of Post-Russia Forumorganised by the Russian opposition in exile and representatives of national movements took place in Warsaw and Prague. There the League of Free Nations (LFN) was formed to develop ideas for new cartographies of the Russian Federation based on independent regions and republics governed by direct democracy with the right of self-determination.

At the last, 4th NFPR Congress in Helsingborg, a memorandum “Terminating the Russian Federation” was signed and the Russian Federation was declared a “bankrupt state”. The direction of thought is certainly encouraging, but further on the congress participants decided to continue meeting online. A common criticism of these congresses is that the statements are made by people from a place of fantasy, and they have no legitimacy or support from below. On the other hand, criticism of nationalisation and the fetishisation of borders comes from left-wing authoritarians, who condemn ideas of disintegration.

In contrast to the ideas of lavish congresses and panic over hypothetical outbreaks of nationalism in the regions, we have seen that amid the mobilisation networks of solidarity have been deployed. They focused their efforts on legal aid for draft evasion, border crossing, and humanitarian support. Links across national borders were updated.

After the announcement of the mobilisation in the Russian Federation, protests broke out in the regions, starting first with mothers from Chechnya, the Republic of Sakha and in the villages of Dagestan, then Makhachkala. Under public pressure, the mobilisation in Chechnya was cancelled, then returned. Representatives from Sakha, Tyva and other ethnic groups have distributed manuscripts and appeals for sabotage in indigenous languages, with ideas to damage and block logistical infrastructures, preventing mobilisation in the regions.

Mongolia helped the Siberian people by sheltering potential conscripts from mobilisation, while Kazakhstan has actively supported Turkic-speaking people by housing fugitives in mosques and other public spaces. The ties that these communities had along cultural, religious, and linguistic lines are now stronger and more pronounced, independent of Russia’s borders and its centre, i.e. Moscow.

We also considermportant the emergence of radical-separatist regional channels that support anarchist practices and call for direct action and anti-war sabotage.

These movements cannot be ignored and should be fully supported. But we cannot expect them to be able to stop the war.

Can the war be stopped by external pressure?

International diplomacy

After the start of the invasion, Russia has shown that it is not going to adhere to any international agreements and humanitarian law. The Russian Federation has preferred military measures to diplomatic ones. The extreme mediaisation of the war has made it impossible to conceal the scale of the Russian army’s war crimes and the genocide taking place in Ukraine. The disclosure of new facts has not affected Russian diplomacy and has only exposed the inability of international institutions to prevent the war and, in principle, to influence it in any way.

All Russian diplomacy boils down to attempts to blackmail the world with a food crisis, the possibility of a nuclear war or an accident at a nuclear power station, or an increase in electricity and heating prices in Europe.

It is impossible to end the war by diplomatic means alone.

Economic sanctions and cutting off economic ties with Russia

The Russian Federation has lived under various sanctions throughout its history.

In general, we can say that not only until the late 2000s, but also until 2014, the rhetoric of détente prevailed, and the sanctions were rather relaxed without having a decisive impact on the Russian economy. But it was not until the invasion of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 that new, more serious sanctions were imposed, some contracts were terminated and open military cooperation with the Russian Federation was curtailed.

In addition to the military-industrial complex, sanctions have been imposed against certain sectors of the economy, the financial sector, specific companies, and individuals.

What is the point of the sanctions and do they work?

It is as if the sanctions are meant to show the state against which they are imposed that the disapproved actions should cease and not be committed in the future. Such sanctions are not imposed immediately, but gradually, giving an opportunity to “fix” at one stage and leaving room for negotiations in the process. In the case of Russia, this logic does not work. There have been no major reversals in Moscow’s policy after 2014. Tactical concessions may have been made in some areas, but overall nothing has changed. Russia has continued to prepare for even greater military expansion after 2014.

In theory, the sanctions should also affect society or so-called “elites” by destroying the status quo, destabilising the political situation and putting pressure on the country’s decision-makers. The problem is that Russian society is not very politicised in principle and has not been able to accumulate enough resources and create the tools to influence the government. There is no such thing as an independent and well-organised elite in the Russian Federation.

Perhaps the picture would be different if the sanctions had a more devastating and immediate effect. So far, the government has managed to maintain the illusion that the situation is normal.

Warfare, among other things, requires economic resources, armaments, trained army personnel, and well-organized supplies and logistics, which constitute the military potential.

Russian armed forces have been officially modernized since 2008 in order to increase them and prepare for new military incursions. There are no internal resources for it.

The Russian military-industrial complex is critically dependent on Western technology*. This is true not only in those sectors in which both the USSR and Russia have traditionally lagged behind, notably microelectronics*. It also applies to the components needed to modernise Soviet weapons models and even to keep the production lines of heavy engineering plants running. Russia not only does not produce enough quality machines and other equipment but also consumables for them.

The 2014 sanctions, while not making cooperation with Russia in the military-industrial complex impossible, have nevertheless made it much more difficult.

Among other things, sanctions were imposed on the extractive sector of the economy. They have not destroyed this sector, but they have made it impossible to develop it further because even here the Russian Federation is critically dependent on Western equipment and specialists.

And this is the most important result of the sanctions today — the reduction of Russia’s military potential, its regular army, mercenaries, and other security forces.

Those are not only the Russian government and businesses that are interested in getting around the sanctions. Western companies, like any capitalist enterprise, are interested in profits and nothing else. Only increased risks and costs due to pressure from politicians and governments from above or loss of image due to pressure from below can make them refuse to feed the Russian military machine. Sanctions and government decrees will not work without public scrutiny. For any business and any cooperation with Russia must become as toxic as possible.

The role of Western components and the stability of production chains

The military-industrial complex has always used civilian enterprises to circumvent sanctions and organise supplies of components, especially dual-use items. Such chains can and should be sabotaged, but this will not reverse the trend — the Russian military-industrial complex will look for any way to gain access to components on which it critically depends. And civilian supply channels will be, and already are, used for this purpose.

The case of the Mistral helicopter could be a good example. France has practically finished the construction but has not transferred the finished ships to Russia*. It was quite a notable and high-profile case. The decision to terminate the contract was made under pressure, which France resisted for a long time. Many military-industrial contracts concluded before 2014 were completed, and in many other cases, cooperation continued as if nothing had happened.

For example, Western countries participated in programmes for the retraining of Russian servicemen both after 2008 and after 2014. Since 2011, the German concern Rheinmetall AG has been building a huge “army combat training centre” — an educational centre and training ground in Mulino: “On a state-of-the-art training ground, 30,000 tank and motorized rifle troops could be trained annually” (*DW). German military experts trained Russian soldiers and officers in modern tactics of warfare and handling of new types of equipment. It was where units of the Third Army Corps formed in August 2022 and were trained before being sent to Ukraine. It was also where the “green men” who took part in the annexation of Crimea* were trained. Some observers say it is the only training ground in Russia that meets modern army standards*.

After the annexation of Crimea, the German government prohibited the concern from completing the contract and “finishing the project 90% complete”. Rheinmetall did withdraw from the project, but only on paper. The project was completed by its Russian partner, Garnizon*. By a strange coincidence, Garnizon imported all the missing equipment from Germany*. In other words, cooperation with the German defence concern continued even after the sanctions were imposed.

In addition, the infrastructure of war is inseparable from the civilian infrastructure. This is particularly true of logistics. Domestically, the main means of transporting goods is the railway. It is extremely vulnerable to acts of sabotage and requires constant maintenance and replacement of rolling stock. All this depends on the supply of specific components that the Russian industry is unable to produce. The withdrawal of just two companies from the market has already put an end to the smooth running of up to 30% of all railcars in the RF and the modernisation of the rest. This reduces the speed of transport across the country and saves the lives of thousands of people whose homes will not be bombed by shells delivered to the front by the railways.

The only way to stop to supplies the Russian military-industrial complex would be not only a complete refusal to supply “dual-use items”, or any products from which anything even potentially useful for the military-industrial complex could be extracted, but ideally a complete break in economic relations with the Russian Federation.

Can the military-industrial complex and other economic sectors in Russia be separated? Is a complete economic blockade necessary?

The political regime in the Russian Federation does not rely on capitalist and legal mechanisms to the extent that most Western regimes do. There is no rule of law in the Russian Federation even in the 1990s, and the Putin regime does not pay much attention to simulating this institution. Instead of the inviolability of private property, there is the institution of loyalty. Loss of trust or unwillingness to share can lead to the collapse or change of ownership of any business. As a result, there is no meaningful business in Russia that is independent of the state. Even local IT specialists, agricultural holdings, or large independent theatres are all affiliated with the state in one way or another and can be completely taken over by state structures at any time.

What to demand and why

A total boycott, sanctions and winding down of activities in Russia

All the resources poured into the Russian Federation support the status quo, i.e. the war. This flow must stop completely. All economic ties with Russia must be severed, whatever the profits.

“We are united in saying that sanctions on Russia must be extended as soon as possible until Putin withdraws Russian military forces from Ukraine. Some now argue that economic pressure cannot influence Russia; The International Working Group on Russian Sanctions fundamentally disagrees: we recognise that tougher sanctions, preventing the flow of revenue and increasing the costs of this war, are no substitute for military and humanitarian aid, diplomacy or other foreign policy instruments, which should be discussed and applied separately. Our focus here is only on one aspect of the larger international strategy necessary to end this terrible war.”

Only a complete embargo on Russian energy will have a significant impact on Russia’s economy and prevent it from manipulating energy access and gas price increases. Only a complete ban on the supply of equipment, excluding all indirect supply schemes through third countries to Russia, will limit the access of the Russian military-industrial complex to the technical components they need for armament.

Although some parts of society have not formed a clear political agenda, they participate in refugee support initiatives and attempt to engage in anti-war activities. Insurgent groups and individuals are active in the country. Support for these activities not only brings Ukraine’s victory and the end of this war closer but also gives hope that revanchist tendencies in the Russian Federation can be weakened.

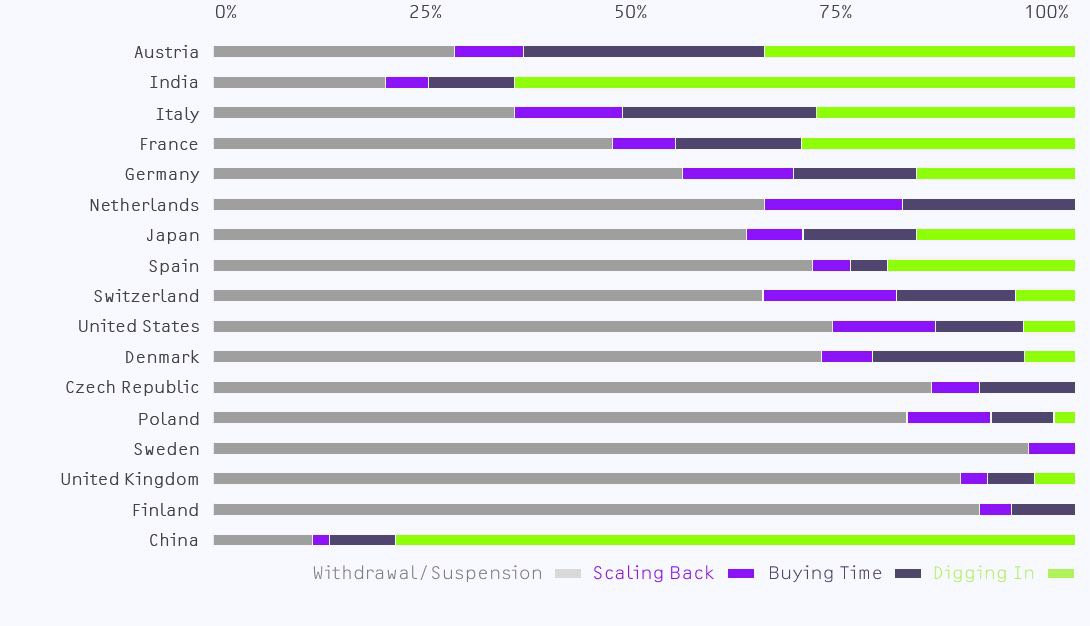

Public positioning of exodus policies by corporations within the Russian Federation

The overwhelming majority of Western brands are quietly withdrawing from the Russian Federation, apparently unwilling to engage in political discussions of any kind and planning to return to the market once the situation has changed. This silence supports the illusion of normality and strengthens the regime, i.e. it supports the war. We should force them to speak out as openly as possible against the war and economic support for the Russian Federation.

Protests in the west against capital cooperation with Russia, opportunities for sabotage

Economic and symbolic power is concentrated in western metropolises. Not only corporate headquarters but also most of the consumers are located in the West. This is why the closer the protests are to the metropolis, the greater the effect they will have in this case. Under pressure from below, many brands are integrating tales of ethical consumption and production into their PR. Businesses need to be helped to turn their faces to the people.

Activists_ on the ground have a great opportunity to engage in small-scale sabotage of supply chains in the Russian Federation and to suppress the public, i.e. propaganda activities of representatives of Russian business and even more so of the state. A huge contribution to stopping the war can be made by trade unions and other workers' organisations in the ports, railways and highways. Any business with the Russian Federation must cease to be viable. If the supplying the Russian Federation and its companies becomes problematic, the war will end sooner.

Objectives:

This campaign aims to initiate a debate about the blurring of boundaries between civilian and military technologies, industries, and capitals. We need more transparency on militarisation.

The open training of military specialists in civilian universities, the outsourcing of military logistics tasks and parts of production chains to the civilian or private sector, and the militarisation of police and other public security structures are not new trends, but they are becoming increasingly alarming. The militarisation of discourse, education, production, and even consumption has little in common with aspirations for emancipation.

To avoid public scrutiny, states are increasingly not only classifying everything related to the military-industrial complex but also outsourcing processes to private enterprises. Militarization is increasingly taking place in a clandestine form. Not only the U.S., but Russia also use PMCs in military conflicts. Moreover, it is PMCs that became the main striking force of the Russian Federation in the war with Ukraine. This makes the already poorly functioning humanitarian law almost completely inapplicable and wars more brutal.

More security and the potential for positive social change in the region, and thus in the world.

The Russian Federation promotes conservative values and authoritarianism, and obstructs positive social change wherever it can. In addition to the Caucasus, the Middle East, and Central Asia, the Russian Federation is increasingly expanding its presence in North and Central Africa. In doing so, the Russian Federation relies primarily on military presence and the military support of cannibalistic regimes. Of course, the Russian Federation is not alone in this, but the less military capability one of the agents of imperialism has, the more opportunities for positive social change there will be throughout the world.

Clarifying the differences between leftist and anarchist perspectives. Criticising the appropriation of the agenda by right-wing and liberal populists.

In Europe, the only politician who support the Russian Federation are the obvious right-wing cannibals and Stalinists. But the active support for Ukraine in many countries has also been linked to conservative politicians using the issue to gain political capital and promote their agenda. We believe that only a complete military defeat and demilitarisation of the Russian Federation can stop the war and bring peace to the region. Attempts to stop the war and genocide should not be associated with the support of the next conservatives and militarists. Exactly to the contrary, this field should not be given over to conservatives and populists.

Disassociation from the tankies, demythologisation of the USSR, and the myths of the Cold War.

Russian propaganda and tankie have succeeded in appropriating the anti-militarist agenda almost entirely. Anti-militarism is what they call blaming the victim and supporting war criminals and autocrats in destroying any disobedience. Forty years have passed since the collapse of the USSR and the virtual end of the Cold War, and they are still feeding us the same old myths and pacifist moralising. Many left-wing and even anarchist structures are affected by this red-brown mould. Their toxicity is not limited to pro-Russian activities but often comes with a host of other problems which prevent our movements from developing.

Methods :

— Organising public actions, blockades, and information events

— Collect and disseminate data on the links between local companies and the Russian military-industrial complex and beyond. We will collect and publish data on these links in each country and transnationally

— Make visible the presence of Russian capital and officialdom in your countries. Squat villas of Russian bigwigs, attack their property, block public speeches by people affiliated with the Russian state and capital. Don’t forget that Russia Today is a Russian state TV channel

— Do not turn a blind eye to the fact that not only among the right-wing, but also among the Western left there are enough people who actively support Putin’s and other cannibalistic regimes. The discussion about this is long overdue and we can finally get rid of this red-brown scum

— Support the Ukrainian resistance and refugees directly and through donations and politics.