PSL, For the Common Good of all

- On PSL’s alleged ties to incel communities and the “manosphere”

- On the accusations of Stalinism and ties to pro-Russian movements

- On military aid to Ukraine

- Why this is being done

- Who we are and what we do

- Afterword. Do the ends justify the means?

Original article in Russian

And how many are there who pretend to look “left”

but see only a black, trembling, rotten human-tower

collapsing to the ground in search of food and water?

Guys, I’ve got some f*g precise and burning insults ready for you.

Galina Rymbu

On October 27, the website syg.ma published a text by the poet Galina Rymbu, titled “Nothing in Common, ” on behalf of the “media resistance group.” It begins with autobiographical sketches and gradually shifts to describing the large-scale Russian missile and drone attacks on Ukrainian cities on October 4–5, including Lviv, where the author lives. Galina Rymbu recounts hiding in a basement with her son and how air-defense fighters try to shoot down drones even with regular machine guns.

She then describes an event on October 5 in Paris — a major anti-war leftist congress and a mass rally where, among others, our comrade from Ukraine, PSL member Andrii Konovalov, spoke. In the same context, she mentions his speech and that of Liza Smirnova (Russia, the “Peace from Below” coalition), characterizing them as “built on calls to limit military support for Ukraine and on emotionally recognizable talking points that in many ways overlap with the narratives of the Russian regime.” Therefore, Galina Rymbu writes, she cannot “not only disagree with their demands to Ukraine’s allied countries, but feel their words as a continuation of the same missile attack — only by other means.” This, she explains, is why she decided to write the text as “an act of personal political agency” and “an expression of dissent.”

Three days later, Galina Rymbu published a second text — an address to Zara Sultan. In it, she summarized her previous piece as follows:

“I criticize their public leaders for cynically working with incels, masculinists, and representatives of misogynistic and neo-fascist movements. I also explain that one of their leaders — a Stalinist and regional secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine — was also a leader of the pro-Russian ‘AntiMaidan’ movement in Kharkiv and a supporter of the ‘KhNR’.

I criticize the numerous statements by the leaders of PSL and ‘Peace from Below’ about the need to stop military aid to Ukraine and about Ukraine being a ‘NATO puppet’ whose people lack agency.

I wrote a personal open letter to Zara Sultan to show how dangerous the support of such Russian left political platforms can be — platforms that manipulate the tragedy in Gaza and the fears of people living in the western part of our continent in order to promote the narratives of the Russian regime and give Putin a chance to seize even more territory.”

Let’s clarify the scope. This article was written by several PSL members who, for safety reasons and given the smear campaign targeting some of our comrades, chose to remain anonymous. Among the authors are people from Russia, Ukraine, and other post-Soviet countries, including queer members. All of them are the members of the PSL. We do not represent or comment on the positions of Liza Smirnova, Aleksei Sakhnin, or any other individuals outside our organization — they can speak for themselves. Our task is different: to examine those points in Galina Rymbu’s text where PSL is attributed words, affiliations, and motives that are not ours, and then to clearly state what we actually say and do. Any attentive reader can check this through open sources: our statements, transcripts of speeches, and reports on actions.

We are not including links due to limited resources; they can be found in the original Russian article. In some cases, references are omitted for lack of time, and in others deliberately avoided to avoid harming individuals. We can provide them on request where needed. In the following sections, we will show where Rymbu’s argument swaps evidence for labels, and where links are replaced by assumptions and guilt by association.

On PSL’s alleged ties to incel communities and the “manosphere”

Let’s start with the core accusation — PSL supposedly collaborating with incel communities and representatives of the manosphere. As “proof, ” Rymbu points to actions mentioned in our November and December 2024 reports: specifically, November 17 in Berlin, and December 21 in Berlin, Cologne, and Paris. By placing these events alongside a Dublin action, she constructs a link between us and men’s-rights activists, the manosphere, and misogynists — primarily through Khorolskyi. In reality, he was the only point of intersection, and even that was limited; none of the other figures mentioned in her text had anything to do with us.

Our overlap with Khorolskyi was episodic and limited to these two Berlin actions. He drew attention only after a left blogger placed a link to his Telegram channel under a video about mobilization in Ukraine. Later, that channel posted a call to attend the November 17, 2024 rally in Berlin against violations of Ukrainians’ rights during mobilization. Andrii Konovalov reacted to that post by leaving a comment asking the organizer to message him privately — he wanted to know whether the event was registered with the police. Such rallies often become targets for provocations. This one, incidentally, was no exception.

On November 17, two separate actions took place in Berlin, and our activists joined both. The first was a rally of the Russian liberal opposition, where we spoke against mobilization and repression. The second was a protest against abuses committed by Ukraine’s recruitment offices (TCC), organized by Ukrainian activists. We supported its anti-militarist message and spoke at the event. Our posters and speeches in German became a visible part of the media coverage, which is why in PSL’s annual report it was labeled as “co-organized” — in the sense that PSL’s presence shaped the public impression in the press. But we did not handle registration or logistical preparation. We did not announce the rally on our platforms, nor did we issue calls to attend it.

Rymbu also links the Berlin actions to the actions on November 17, 2024 in Dublin and concludes that there was supposed “joint coordination” involving PSL. This is incorrect. PSL has no members or structures in Ireland; the actions in Dublin were organized by a separate local group unrelated to PSL. We did not take part in planning, communication, or media work around them. At the time we attended the Berlin action, we were not even aware that a group in Dublin existed.

Rymbu’s claim that Khorolskyi “co-organized” the rally relies on a Telegram post by SOTA — but the post refers not to the November 17 actions, but to the December actions in Berlin, Cologne, and Paris, which were organized by us and did not involve Khorolskyi or anyone similar. The SOTA post, in turn, is largely based on a summary by Ukraine’s Center for Countering Disinformation, an institution that, in wartime conditions, engages in counter-propaganda, constructs fictitious links, and discredits any voices critical of the war or the Ukrainian authorities. The conclusion about “joint coordination” is built on information from this Center and on a chain of secondary sources of questionable accuracy, where dates are mixed together and factual connections are replaced with assumptions.

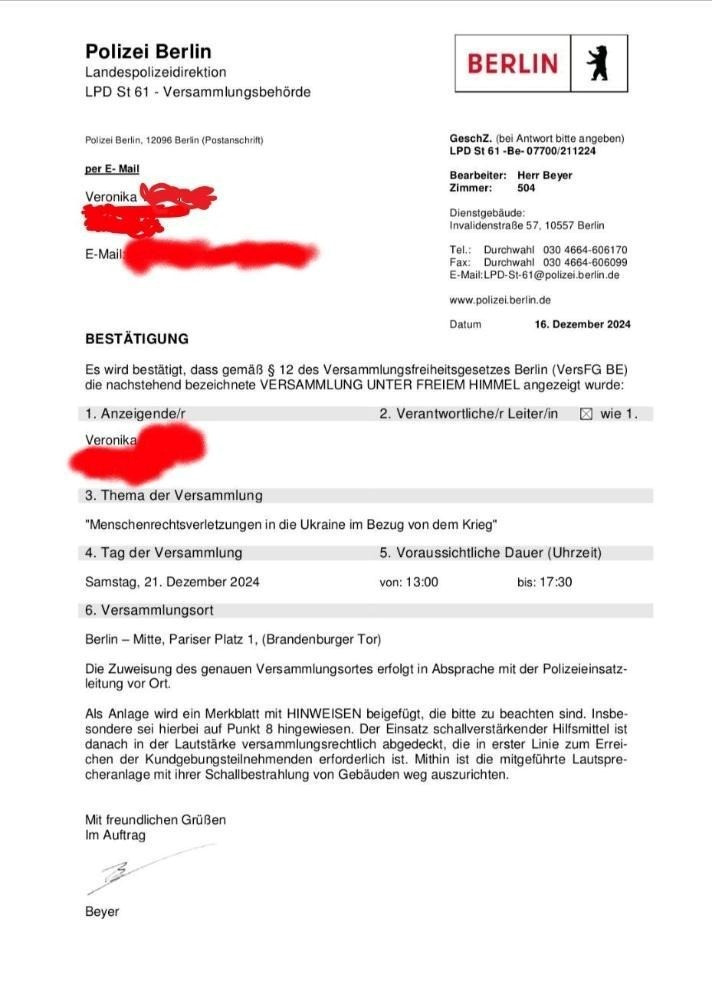

We organized the December actions ourselves. The Berlin event was officially registered under the name of our supporter Veronika, as confirmed by the registration documents.

The next round of accusations was triggered by a short video clip in which Khorolskyi simply shows the location of the action — the Christmas tree on Pariser Platz. It contains no statement and no political content. Yet in Rymbu’s text, this fragment is interpreted as “actively promoting Khorolskyi’s personal content.”

That was the end of the overlap. There were no further contacts — something confirmed by a former PSL member:

“What concerns Berlin, according to the activists, Serhii Khorolskyi was present there. To be honest, reading Rymbu’s text was the first time I learned about this person. Before and after that, there was no active cooperation with him on behalf of the organization.”

If you put everything together, the picture looks very different from what Rymbu describes: PSL members did not publish Khorolskyi’s materials, did not promote him, and do not share his misogynistic or anti-feminist views. At our meetings — in Göttingen, Saarbrücken, and other cities — we were talking specifically about defending the rights of women and queer people. In the article, however, a one-off episode becomes a “connection, ” coincidence becomes “coordination, ” and simply being in the same public space is turned into alleged support for the manosphere.

The author constructs her argument like a police report: “knew, crossed paths, stood nearby.” This is not factual analysis but the assembly of a narrative through associations: “stood next to someone → must be together, ” “knew about the rally → must support it, ” “mentioned in the same channel → must share a line.” This kind of logic does not clarify the situation; it simply produces the accusation that was needed.

This kind of argumentation resembles not feminist critique or political analysis, but a mechanism of discreditation, where a mere hint is enough to declare a “connection.” First a target is chosen, then fragments are collected to assemble the desired narrative. That’s how the illusion arises that scattered episodes form stable ties.

Just as participating in rallies of the liberal opposition does not make us liberals, and just as liberals do not become supporters of far-right views by attending actions where far-right formations like the RDK are present, the fact of being at an event organized by dubious figures does not mean that we share their positions or are in any political alliance with them. Sharing a space is not the same as sharing a political stance. And full ideological unity at public events is simply impossible to demand.

At the same time, we believe it’s important to pay attention to who appears in shared political contexts. When activists of the Union of Maoists of the Urals — previously exposed for sexualized violence and abuse of power — showed up at one of our events in Hamburg, the response was unambiguous. As former PSL member Denis recently wrote:

“We publicly condemned their actions and demanded that they leave the venue, unwilling to have anything to do with people involved in sexualized violence and abuses of power.”

It’s also important to keep the organizational context in mind. At that time, PSL was a small initiative group: a few people handled leaflets and visuals, and almost all coordination and communication went through a single activist. Under such conditions, decisions are often made quickly and situationally. This is not a “political line” or a set of “alliances, ” but the ordinary reality of grassroots volunteer activism.

In Rymbu’s text, these situational interactions are presented as stable ties and deliberate coalitions. Ignoring the scale and working conditions becomes a tool for giving isolated episodes a weight and meaning they never had.

Mistakes happen, and turning them into grounds for public shaming and for labeling people “misogynists” means playing by the media rules of Russian propaganda. And the “battle for hearts and minds” methods now being applied to us are not leftist practices — they are the practices of those fighting against us.

There is something else worth noting. Among those who are now spreading accusations against PSL are people who themselves collaborated with bloggers who directly promoted Khorolskyi and advertised his channel. None of them, however, became targets of criticism in Rymbu’s text.

In other words, the choice of target was selective. Where criticism could be directed at those who genuinely promoted Khorolskyi, none was offered. Meanwhile, two brief episodes of PSL’s contact with Khorolskyi were inflated into a supposed “connection.”

This selectivity is not driven by a fight against “misogynists entering the left movement, ” as some texts frame it. If this were truly a matter of principle, the primary criticism would be aimed at those leftists who interacted with Khorolskyi in Berlin stand-up clubs and directly promoted his channel. Yet these people remain untouched by critique.

On the accusations of Stalinism and ties to pro-Russian movements

Another accusation concerns the activities of our member Viktor Sydorchenko — a Ukrainian citizen who has lived in Germany since early 2022. The charges against him rest on the fact that he was a member of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), and that in 2012 he dared to run as a parliamentary candidate for the CPU in the elections to the Verkhovna Rada.

The author claims that in 2014, after Euromaidan, Viktor supposedly took part in organizing the March rallies in Kharkiv associated with the so-called “people’s militia.” Those rallies included calls for a regional referendum and expanded autonomy for the Kharkiv region. Some publications describe these events as involving the CPU, the organization “Borotba, ” and certain far-right groups.

From there, the argument shifts to guilt-by-association. Rymbu refers to a piece on the resource “Nihilist, ” which claims that some former CPU members later held prominent roles in “Borotba, ” a movement said to be influenced by Vladislav Surkov. She also points out that Oleksandr Fedorenko — mentioned in reports about attacks on Kharkiv anarchists in 2014 — co-founded the charity foundation “Angel” together with Viktor Sydorchenko.

The entire “threat biography” constructed out of these fragments collapses the moment one checks the dates. Viktor resigned from his position in the regional party committee on December 6, 2013, due to family circumstances, and left Kharkiv before the Kharkiv events began. His employment record book confirms this. He physically could not have participated in the “Anti-Maidan” rallies or in any “people’s militia” structures.

In the article Rymbu cites, his name does not appear. Not a single referenced source contains any mention of his participation in the events of 2014. The only indirect appearance is a note in the CPRF newspaper Pravda from March 2014, where he is listed as head of the ideological department of the CPU regional committee (though he had already left the position by then) and speaks about federalization — a line that Rymbu, conveniently, removes from her quotation.

The “Angel” foundation was indeed created together with Oleksandr Fedorenko — but this happened in 2006, long before the events of 2014 and long before any of the political splits that today’s accusers are trying to invoke. In practice, the foundation never began full activity. Among its founders, besides Viktor, were also Pavlo Tyshchenko and Dmytro Yakush, who is currently serving as a volunteer in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. None of this context appears in Rymbu’s text — instead, she opts for a convenient associative link based on “name proximity.”

Before the war, Viktor worked within the structure of Ukroboronprom — at the Malyshev Tank Factory, where he served as head of the press office, handling communications on Ukrainian defense production and investment outreach. Accusing someone of “pro-Russian views” while ignoring years of work inside Ukraine’s defense industry is not analysis — it’s narrative construction, cutting out everything that contradicts the intended storyline.

Viktor is preparing a detailed text in which he will lay out the sequence of events and his own position. It will be published separately.

But even now it’s clear that instead of analyzing the concrete actions of a specific person, the text builds a schematic chain of associations: Sydorchenko once belonged to the CPU → some former CPU members later adopted pro-Russian positions → therefore PSL is “pro-Russian.” This is not an argument; it’s a mechanical transfer of a label: past = present, one member = everyone’s position.

The history of the CPU and its members after 2014 is far more complex. Some indeed shifted toward pro-Russian positions. Others remained in Ukraine and engaged in very different initiatives, often in direct conflict with each other. Many former CPU members serve in the Ukrainian Armed Forces and directly contribute to the country’s defense. These people have a far more tangible connection to Ukrainian security than the author of the accusatory text.

Reducing the CPU — the largest left party in independent Ukraine, with more than one hundred thousand members in 2014 — to a single political trajectory just because some former members went in a certain direction means ignoring the real political landscape and replacing analysis with label-based reduction. The same applies to the supposedly uniformly pro-Putin “Borotba.” While part of its leadership indeed took a pro-Russian and unacceptable position, a significant portion of other former members can be found in Social Movement, in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, and in Ukrainian migrant initiatives. And this includes not just rank-and-file members: one of the former leaders and co-founders of the organization, Serhii Kyrychuk, appeared on Ilya Ponomarev’s platform in April 2022 expressing support for Ukraine.

Rymbu repeatedly emphasizes the “non-representativeness” of our organization within the Ukrainian left, yet her material suggests she has a rather superficial understanding of the Ukrainian left movement as such. Pointing to the “correct” Ukrainian left, she ignores the fact that even among them there is no consensus on whether Social Movement itself should be considered a genuinely left and democratic organization.

On military aid to Ukraine

Another line of criticism concerns our position on military aid to Ukraine. Our position is simple and consistent: we support the right of Ukrainian society to self-defense. At the same time, the means matter. We consider mobilization violence, repression against anti-war activists, and pressure on left movements inside Ukraine unacceptable. External defense aid is legitimate only under conditions of democratic oversight and only if it does not involve suppressing those who oppose the war. We distinguish between the Ukrainian people and the Ukrainian state, and our position aims to protect the former, not to strengthen the power of the latter.

In Rymbu’s text, this complex and concrete position is deliberately turned into a caricature: “if you oppose unconditional escalation of arms deliveries, then you’re for the Kremlin.” This is a familiar schema that shuts down political debate and replaces arguments with accusatory labels.

The criticism of our position is built on simplification: we are portrayed as people “against military aid to Ukraine” in general, and thus assigned naïve pacifism or a pro-Russian line. In reality, we are talking about something else. At the rally mentioned above, Andrii Konovalov expressed the position with full clarity:

“According to Ukraine’s Prosecutor General, in just the first six months of this year around 125,000 people deserted or evaded service. These are people who did not want to take part in the war. Standing with Ukraine means standing with these people, with your own society — not with those who secure safety for their families by forcing others to give up their lives. Freedom cannot be built on coercion.”

And further:

“The first step European governments could take would be to link military assistance to conditions requiring the Ukrainian authorities to reduce the scale of lawlessness and torture of their own citizens. But we see nothing of the sort. These deliveries have nothing to do with freedom, democracy, or the interests of the Ukrainian people.”

Thus, the issue is not “reducing support for Ukraine, ” but preventing military aid from turning into internal violence and repression. Ignoring this is precisely the substitution on which the criticism rests.

The same position is stated on our official website. We support military aid only if it is tied to concrete conditions: repeal of decommunization laws, discriminatory language norms, recognition of minority language status, and the dissolution of ultranationalist paramilitary formations. The authorities must also commit to resolving disputed questions democratically — through independent referendums under international supervision and without pressure or the presence of armed forces from either side.

So when Rymbu writes that our words “sound like a continuation of the missile attack, ” we cannot agree. To distinguish is not to justify aggression. It means being able to see war not as a sacred cause but as a human catastrophe, where the means matter.

And speaking of means: the author criticizes us for supposedly justifying good intentions with bad methods — as if under the slogan of peace we excuse inaction in the face of evil. But in reality she does exactly that: under the guise of defending freedom, she justifies excluding any voices that don’t align with the pro-war position. Her goal — victory of the Ukrainian state — justifies everything: militarization of society, repression of dissent, labeling opponents as “Kremlin agents.” Any attempt to set conditions for military aid is denounced as a moral offense.

The irony is that while accusing us of compromising with violence, she legitimizes right-wing violence — just in the “correct” direction. This is the mirror logic of war: good permits itself everything it condemns in evil.

Galina Rymbu writes:

“Every day I see Ukrainians of very different political views resisting Russian military aggression, defending their right to independence, organizing social movements, protests, grassroots mutual-aid networks — despite the extreme conditions of war.”

She speaks of “different views, ” but lists only those who fit within the narrow range she has defined: those who support the front, the authorities, and the very logic of “war until victory.” She does not mention those in Ukraine who face pressure and torture for refusing to fight, opposing mobilization, or demanding negotiations.

And there are many such people. Those who go through the recruitment offices where people are grabbed on the streets and beaten. Those who document violence by the army and local administrations. Those who — like our comrade Andrii Konovalov — were forced to leave the country because of persecution for an anti-fascist position.

Rymbu reproaches PSL for supposedly “speaking on behalf of Ukrainians, ” yet she herself sometimes invokes “many” or “most” without reliable data, leaning on a homogenizing rhetoric of “the people.” Meanwhile, Ukrainian citizens are not only present in our organization — they write the statements about their own country themselves and cooperate actively with independent left groups inside Ukraine.

Victims of Ukrainian repression need solidarity, not moral sorting into “real” and “not real” Ukrainians. And the mutual exclusion of dissidents and the pulling apart of actual Ukrainians into opposing camps is precisely the goal of both Putin and Zelensky today.

As for Andrii Konovalov’s speech — delivered not in the Bundestag or the National Assembly or the House of Commons, but at a left congress, criticizing his own government and arguing that “the billions poured into weapons must be tied to concrete measures that the Ukrainian authorities could take” — how appropriate is it to reduce his speech to “a continuation of the same missile attack — only by other means”?

This statement sets the tone for the entire text. The author collapses the distinction between physical violence and political speech, and then builds the whole narrative around her personal trauma: disagreement becomes an “attack, ” and the opponent becomes a “threat.” This is a literary device, not an argument. A public position — even an unpleasant one — is not the same as the use of force. By mixing these registers, the author shuts down the space for politics and reflection altogether: discussion of the goals and means of war is replaced with moral panic.

If any disagreement is experienced as a continuation of shelling, then an opponent does not need to be argued with — they need to be “silenced.” This produces a climate in which the only one who is right is the one who shouts the loudest or hurts the most. It erases the agency of those who think differently.

The metaphor “words = missiles” ends up labeling as “dangerous” not only us but also that part of Ukrainian society that simply holds a different view on the prospects of the war — and therefore, in practice, can be not only ignored but also grabbed on the streets, shoved into vans, sent to the front, and stripped of the right to call themselves Ukrainians, all in service of a right-wing national myth. By legitimizing her own view through a traumatic biography, the author simultaneously denies others the right to complexity, casting them as “continuers of the attack” or “pro-Putin forces.”

Galina Rymbu calls herself an anarchist. We did not delve into how anarchism can be reconciled with supporting a regular state army, let alone serving in it. But we did express our surprise by referring to a statement from the Berlin Anarchist Bookfair. It concerns their refusal to give a platform to a pro-war presentation by ABC Belarus and the Solidarity Collectives, and the subsequent media campaign accusing the fair of canceling and silencing “Eastern European voices.” We did not get into the details of that conflict, but the organizers’ response seemed clear and consistent enough that we decided to quote it here:

“The war has been going on for more than three years, and there is no end in sight. The Ukrainian army receives from the US and Europe just enough support for Putin to remain satisfied with the slow advance of Russian forces — as long as he doesn’t reach for the nuclear button. Since the Ukrainian military blocked any idea of an anti-authoritarian unit, and since the Kursk offensive was pushed back, anarchist revolutionary ideals have played no role whatsoever in this war. If by saying ‘not our war’ the author means ‘not an anarchist war, ’ we fully agree. It can be called anti-imperialist or anti-fascist, but not anarchist — and certainly not anti-authoritarian. We rarely encounter this kind of analysis from anarchists for whom joining a state army is the main path. Nor do we see attempts on their part to engage in equal dialogue with anti-militarists.”

Unfortunately, in wartime even the most “democratic and anti-authoritarian” structures tend to drift toward uniformity and submission to hierarchies. And debates collapse into deciding who counts as an ally and who does not.

We firmly distance ourselves from that part of the Russian-speaking diaspora that calls itself “left, ” yet in practice works to strengthen militarism and serves interests external to the Ukrainian people — believing this somehow washes away their share of responsibility for Russia’s war against Ukraine.

It is both possible and necessary to continue discussing what kinds of conditions for supporting Ukraine should exist and of what nature. To clarify our stance further, to make it more balanced and grounded. We remain open to discussion and criticism in that direction.

On the accusation of “denying Ukraine agency”

One of Rymbu’s main claims is:

“…in the speeches of ‘Peace from Below’ and PSL leaders, Russia’s war against Ukraine is presented only as a war between two ‘imperial forces’ — the US and Russia, which erases Ukraine as an equal political subject and negates its agency.”

This formula is convenient for ostracizing dissent but dishonest. First, we have never claimed that Ukraine is a “NATO vassal” or a “Western puppet.” There is not a single direct quote supporting this. We are saying something else entirely: that in any war a nation-state inevitably becomes dependent on global power blocs, and acknowledging that dependence is not a denial of agency but a sober assessment.

Second, it is we who insist on Ukrainian agency — but we understand it not as the agency of the state, the regime, or the authorities, but as the agency of the people in all their diversity, including those who disagree with the government or reject mobilization. Unlike our critics, we believe that alongside the right to self-defense, Ukrainians should also have the right to self-organization and to resisting their own authorities.

When Rymbu writes that anti-colonial wars require “strong allies” and that “an empire cannot be defeated alone, ” she is in fact agreeing with our point. Only she acknowledges structural dependency in one paragraph, and in the next accuses us of noticing it. Recognizing the structure of dependency is itself a step toward subjectivity.

You can talk about real independence only when you understand the boundaries within which your freedom operates. Our anti-imperialism is therefore not about mirroring empires, but about the people caught between them. About those forced to maneuver, lose, survive — and still remain subjects even when both sides demand they stand under their respective banners.

But what do Ukrainian left voices themselves say about agency — people who give interviews under pseudonyms even in exile?

“It’s important to pay attention to what is actually happening within Ukrainian society, what conflicts exist or are emerging. Because unfortunately, for the left — both in Russia and in the Western public sphere — Ukraine is seen exclusively as a victim or as some kind of Eastern European Sparta. Of course, it is a victim in the sense that the world is divided into nations and states, and these nations and states, like billiard balls, either collide or fall apart. But that’s not enough. This is a theoretically impoverished way of thinking.

When the left — including Russian leftists — make declarations that ‘we also need Ukraine’s victory and Russia’s destruction, ’ they believe they are granting Ukraine some agency. But you can also see it differently: they are taking agency away from the people living there, or they assign the agency of one particular group to everyone.

If you look at what has been happening in Ukraine over the past year, it’s a very grim picture. The lines of division emerging now have little in common with those formed after Maidan and the revolution.”

So when we are accused of “appeasing the aggressor, ” our answer is: no — we are talking precisely about recognizing the diversity of Ukrainian voices, about the right of each person to be a subject rather than an object used to legitimize one group or position over another.

The only quote the author managed to produce that supposedly questions Ukraine’s agency is a line spoken by the host of a YouTube program in which our members participated. In that broadcast, the host — Serhii Krupenko, a member of the Central Committee of the RCP (I) — introduces the discussion and calls Ukraine a “puppet state.” This is on the same level as the other claims she repeats: that Mélenchon supposedly funds PSL, or that Konovalov makes antisemitic videos in German. Neither is true.

By listing various people and organizations side by side and spreading the motives and actions of some onto others, the author continues to manipulate. This is the core strategy of the text — guilt by adjacency. It doesn’t matter what you actually say; what matters is who once happened to appear next to you in a photo, a broadcast, or a hyperlink.

Why this is being done

Rymbu’s goal is not dialogue and not analysis, but ostracizing the inconvenient and narrowing the left to a circle of people who are “acceptable” on the questions of continuing a bloody war and of whitewashing or denying Ukraine’s domestic political problems. A certain segment of the Ukrainian left (and the Russians aligned with them) is trying to portray PSL as a toxic, authoritarian actor.

Unlike those who knowingly or unknowingly move in the slipstream of the Ukrainian state mainstream, we understand that for many leftists inside Ukraine this is a matter of survival; not everyone is prepared to go to prison or face isolation — especially Russians living in Ukraine. But we should not forget that the more oppositional part of the Ukrainian left is forced to confront daily repression, raids, threats, and false accusations of being “pro-Russian.”

We remember the case of Bohdan Syrotiuk, imprisoned for his principled political and anti-war stance — a figure unwelcome both to Ukrainian anarcho-statists and to certain Russian leftists. We remember the regular raids against supporters of the RFO, independent antifascists in Ukraine, and unknown communists whose “crime” was reading uncomfortable books, raising uncomfortable topics, and asking uncomfortable questions.

Moreover, we consider it entirely natural that the future of this part of the Ukrainian left lies in a close political alliance with genuinely anti-war Russians, Belarusian citizens, leftists from Central Asia and the South Caucasus, and the anti-militarist movement in Western countries. We are convinced that all these groups of independent leftists have far more in common with each other than with the politics of any state.

Predictably, this provokes aggression from those whose dualistic narratives cannot accommodate this. This happens because for years these actors have tried to present themselves as the sole representatives not only of Ukrainian society but as the only “true” Ukrainian left. People who call themselves anarchists, democratic socialists, and anti-authoritarian activists fight dissent against themselves so aggressively and authoritatively — using slander, harassment, and denunciations — that their behavior is comparable to the most grotesque images of past repressions.

The problem is that most of the slogans of the broader opposition are liberal slogans that construct an enemy image. They mobilize not only against Putin, but against anyone on the vaguely “pro-Putin” side — even someone broken and abused by the system. Any person from the provinces who watched TV and said something “in support of Donbas” becomes an enemy in this framework, which means dynamite is being placed under society itself. And the liberal movement only drifts further away from the people.

— Galina Rymbu

Who we are and what we do

This text was never meant to exist. At first, we did not plan to respond to the writings of the poet, translator, feminist, and anarchist Galina Rymbu, because we saw them simply as defamatory and unable to withstand even minimal critical scrutiny. So we limited ourselves to a short statement.

But our surprise was considerable when people who seemed close to us in views and values — as well as some media platforms — simply swallowed this dishonest text. Rymbu’s piece “Nothing in Common” spread across the left Facebook sphere, cultural circles, and activist networks, carrying with it a package of manipulations, open lies, logical substitutions, factual errors, and calls for harassment and ostracism. Our response is not only an answer to the accusations but also a call. Here we want to echo and thank our comrade and former member Denis Kozak for his appeal to the left to take care of one another.

The Union of Post-Soviet Left (PSL) is made up of researchers, activists, students, artists, social and humanities workers, and ordinary workers from Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, and the countries of Central Asia. In the European Union, we are migrants, refugees, deserters, and draft evaders who have all, in one way or another, experienced the consequences of repression and war.

Since the start of the war, we have been translating for refugees in hospitals, accompanying them to government offices, filling out documents, helping them defend their rights, set up interest groups, and even organize a concert for Ukraine’s Independence Day. We continue helping Ukrainian refugees and draft evaders defend their rights.

It is precisely through interaction and contact with real people from war-affected areas — many of whom have lost loved ones and homes — that our political understanding is formed. Among the people we’ve worked with are many who want negotiations, a truce, a pause. And there are those who support “defense at any cost.” And we listen to them, because they are Ukraine too.

Our perspective cannot be reduced to either Russian or Ukrainian left politics, much less to the positions of individual activists. We organize on democratic principles, without leaders or hierarchy, with differing views on specifics but united by common principles and values.

We cannot simply be declared “pro-Putin” if one actually follows our work. We deal not only with material and informational support for deserters, but also with lobbying at the pan-European level to have desertion recognized as an act of political dissent and a sufficient basis for political asylum — while some of our critics publicly claim that encouraging desertion from the Russian army is “inappropriate.” Moreover, we openly argue that the Ukrainian draft-evasion movement should cooperate with the movement of Russian draft evaders and deserters. At our rallies for Ukrainian ukhylianstvo, we literally had Russian speakers voicing support for the Russian anti-war movement.

We are also categorically opposed to any external support for Russia and believe that even now there is room to resist it. For example, we publicly raised the issue of North Korean assistance to Russia in its war against Ukraine.

Our organization has provided and continues to provide support to anti-war Russians imprisoned in Central Asian extradition jails for their anti-war views, and we support fundraising efforts for Russian political prisoners and organize letter-writing evenings. In just over a year, we published the fifth print run and second edition of brochures on Russian left political prisoners. Their content is explicitly aimed at turning Western leftists away from the Putin regime and includes practical proposals for solidarity campaigns. The publication of these materials has been repeatedly thanked by support groups and the prisoners themselves.

We also regularly hold events on repression in Russia, where we state directly that for Western leftists the Russian Federation cannot even hypothetically be considered an ally, and we support campaigns against repression of allied initiatives. We are working to launch a campaign in support of continuing humanitarian visas precisely so that anti-war citizens of Russia and Belarus have somewhere to hide from war and persecution.

Galina Rymbu ignored all of this entirely, basing her accusations on openly isolated and unchecked claims.

And most importantly, we fully support radical change in Russia and believe such change is impossible without close cooperation with the political forces that continue resisting inside the country. We have not broken ties with the resistance within Russia and actively support it, trying to account for its interests in our work.

Our strategy in this area is straightforward:

— supporting anti-war and social movements and left organizations inside Russia;

— expanding asylum rights and protection; expanding the desertion movement;

— punishing war criminals, not Russian civilians;

— working with leftists in Western countries, the CIS, and the Global South; countering sympathy for the Putin regime;

— exposing the imperialist role of the Russian Federation and the CSTO in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, the South Caucasus, Syria, and African countries;

— identifying pressure points on the Russian regime to force an end to its aggression.

On all these fronts — and other areas of resistance to the Putin regime — we are ready for dialogue with any consistent left forces.

At the same time, we cannot ignore the role of global capital in Ukraine, just as we cannot ignore the role Russian capital played before 2014. Possessing not only material power but also discursive power, capital shapes reality by naming it. The West calls its militarization and expansion of military capacity “aid” to Ukraine and “strengthening Europe’s defense capability, ” all at the expense of Ukrainian citizens. Under this pretext, weapons production is rapidly expanding — including systems and ammunition for large-scale war. The US, Germany, France, Norway and others are restarting production of M777s, HIMARS, IRIS-T, Aster, and Patriot systems, while Trump demands increasing NATO countries’ military-spending target to 5% of GDP. Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion, Rheinmetall’s stock has risen by 2000%. Europe’s largest arms manufacturer is triumphantly opening new ammunition factories in Germany and Latvia, while Germany is trying to bring back mandatory military service.

This kind of “aid” is not in the interests of Ukrainian workers and leads to the militarization and consolidation of right-wing regimes taking shape in the US and Europe. It fuels new cycles of escalation and makes ending the protracted war impossible.

We believe all this contradicts the interests of the working class of Ukraine, the US, Germany, Latvia, Russia, and every other country. If we are supposed to keep silent and wait until capitalists settle this conflict among themselves, we deprive ourselves of the right to reclaim political space and agency — leaving that ground to the right. We strip the left movement of meaning today and in the future.

Afterword. Do the ends justify the means?

I’d like to end with what Galina Rymbu ends her text with: the question of ends and means. We doubt that any consistent left or democratic force wants a “Russian victory” — meaning the destruction of Ukrainian independence and the turning of the country into a subordinated territory.

From inside Ukraine, under bombardment, Rymbu is right about one thing — it is important to remember who started this war. And we do remember. We rule out cooperation with people and organizations that ignore Russia’s aggression, or worse, imagine Russia as some decolonial agent allegedly resisting Western imperial expansion.

At the same time, after three years of war and hundreds of thousands of victims on both sides, what seems responsible to us is not unconditional support for all actions of the Ukrainian state with all their accompanying problems, but recognition of the agency of its people and the diversity of their voices — voices that continue to exist both there and in exile. When hundreds of thousands of deserters refuse to fight, and their number keeps growing. For the left, standing with Ukrainians should therefore mean not unconditional support of state goals, but starting a difficult conversation about means, building channels of communication with Ukrainians in Europe and on the ground, debating and organizing together already now.

We call our response “For the Common Good of All” because what needs protection today is precisely the common — the human, the universal, the vulnerable. What matters to us is not state borders or national interests, but the fate of the majority: those who work, survive, lose, bury, flee.

We reject the logic of the “lesser evil” because it always legitimizes new evils and pushes us further away from resistance itself. It creates new resentments and hierarchies of suffering, discrimination, and humiliation. And most importantly: it brings us no closer to ending the war nor to changing the regime in Russia.

We call on everyone committed to left, democratic, and uncompromising positions toward war, violence, and exploitation to get in touch and join us. Together we will continue building a new bloc of internationalist forces around the world — a bloc that can answer the global militarization and the preparation for a new world war. And the current rise of the right, anti-migrant sentiment, militarization, and fascisation shows just how crucial it is to reclaim the language of solidarity — a language that has room not for enemies and flags but for people and common struggle.

That is why we write — for the common good of all.