Guzel Yusupova. Mapping the Future of Russian Studies

The failure of most foreign researchers and experts on Russia to anticipate Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and to explain the public reaction to it has once again made visible the huge gaps in the studies of Russian society. Moreover, it has become obvious that the state of society as a whole and its parts, even in an authoritarian state, is very important and affects its ability to wage wars.

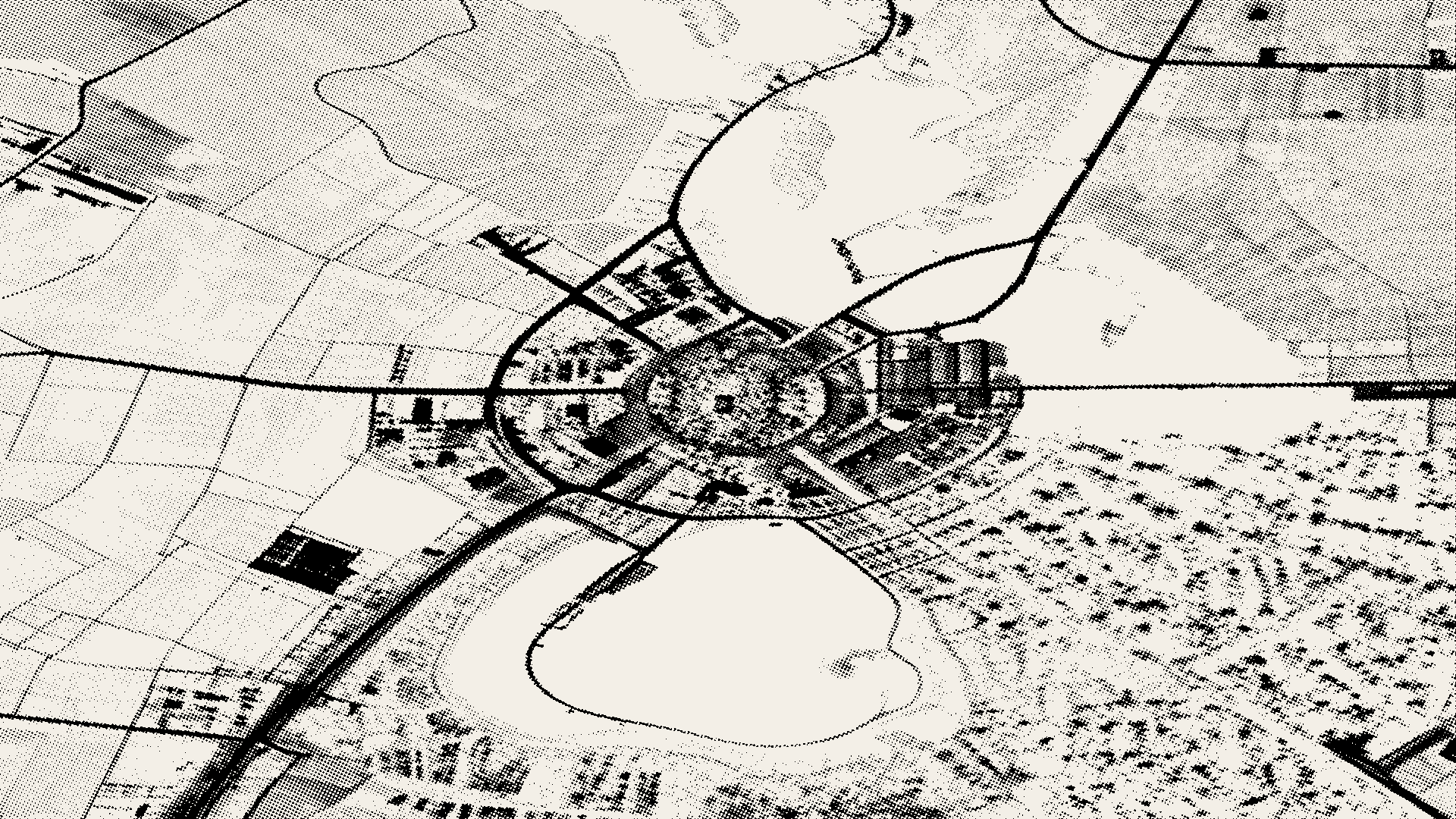

In her essay for the Atlas project, Guzel Yusupova, a political sociologist and Humboldt research fellow at the Institute for East European Studies at the Free University of Berlin, argues that truly understanding the processes happening in Russian society today is possible only if we consider its heterogeneity and diversity, which are shaped by various forms of historically established inequalities.

In her opinion, only a redistribution of academic attention from the study of capitals to the periphery, and from Kremlin politics and protests to social processes within different groups of society will help to bring about a new political agenda that can eventually result in a significant social change. Read more in the new material from the Atlas project, with illustrations by Sonya Umanskaya. Publishing Editor — Konstantin Koryagin.

Версию текста на русском читайте здесь.

- Introduction

- 1. Russia’s 80+ provinces should be studied at depth from an interdisciplinary perspective

- 2. Local research agenda and local researchers should be supported on many levels

- 3. Promotion and legitimation of critical approaches to understanding of Russian society

- 4. Greater emphasis on the impact of the Soviet and Imperial past on present transnational and translocal relations

- 5. Communication of local knowledge and knowledge on local issues to wider audiences

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

Introduction

The current Russia-Ukraine war has revealed many blind spots in social scholars’ understanding of how Russian politics and society work. Some previously overlooked areas suddenly became crucial for developing effective policy responses that can limit the power of Russian elites. However, academic and public discourses of Russia before the war lacked many debates that can be important for deeper understanding of Russia and designing constructive European policies.

One of the surprises, which at first glance may seem paradoxical, is that society as such still matters to top-down domestic politics and in turn affects international relations, while before it was deemed much less important for “big politics”. Putin’s fear of announcing the mobilization in March 2022 when it was most relevant to the war outcome is the most telling case of how society matters even in dictatorship. Society’s response to the new realities of the war informs the decisions of Russian political elites and affects the Russian economy now even more than before. Putin’s fragile balancing act between the interests of elites, security apparatus, oligarchs and the population (Frye 2020) has been jeopardized by this war and popular support has become the crucial factor for keeping him in power. Popular support matters not because social protests will certainly lead to revolution, but because they make room for political cleavages in personal authoritarian regimes such as Russia, where a decline in approval of the leader changes everything. Moreover, the organization of Russian society also matters to other political developments and outcomes including but not limited to the numbers of conscripts or emigration from Russia.

The most striking realization for scholars of Russia was that Russian society is not homogeneous but consists of a number of groups shaped by various forms of inequalities. These inequalities are shaped historically and have a huge impact on how the Russian public reacts to the war. However, the profound inequality in Russian society has been largely overlooked by Russia observers and analysts. In such a territorially vast country like Russia, economic inequality overlaps with spatial inequality, while the latter often has specific cultural traits due to history of settlement. Thus, many layers and forms of inequality overlap and strengthen one another, while others contradict each other and leave space for limited social mobility. The complex nature of social stratification of Russia, however, was rarely the main focus in research on Russia. Instead, the political elites and public intellectuals as well as their discourses were at the center of scholarly investigation. The time has come to change this and to look deeper into Russian society in all its complexity.

Russian society is not homogeneous but consists of a number of groups shaped by various forms of inequalities

Ethnic and cultural diversity and their hierarchical nature have suddenly appeared as something new to Russia observers. However, it was always there. Russia was never homogeneous; it is and always has been immensely diverse. Russian territory consists of over eighty provinces, each with its own history of accession, economic development and mix of cultures, religions and ethnicities. However, the current Russia-Ukraine war is going under the ideological narrative of Russkii mir (Russian world) and Russian propaganda has been successfully exploiting it, therefore even the smartest observers forget about the inherent Russian diversity and are misled by the discourse that is created from above. While many Russia analysts use the figure of 80% of ethnic Russians as the argument for calling Russia ethnically and racially homogeneous, it is important to acknowledge two factors shaping the rest 20% of non-dominant ethnic groups: ethnicity in Russia is often linked to a territory and huge wave of incoming migration from the traditionally Muslim countries of the post-Soviet states also have great impact on Russia’s cultural diversity. Some observers (Laruelle, 2016) point out the increasing Islamization of Russia due to migration and demographic trends of higher birth rates in traditionally Muslim localities. These two features of Russian diversity — territorial and cultural — shape a very important context for understanding Russia’s nation-building processes and as a consequence, its domestic and foreign politics.

Although scholars have already asked questions about Russia’s nation-building and many books have been written on the topic of Russian nationalism (Verkhovskii and Pain 2013, Laruelle 2009, 2021, Goode 2016, Kolsto Blakkisrud 2016) and indeed on the historically embedded cognitive structures that shape the overarching Russian identity today (Sharafutdinova 2020), there is the lack of studies focusing on identity politics in Russia. Research addressing the racial, ethnic, class and gender issues that together shape common understandings of Russian nationhood and belonging is also scarce, although some excellent studies have dealt with these themes in the 1990s, when the real federalization of Russia took place (Giuliano 2011, Gorenburg 2003, Hakim 2007). Since the 2000s, the studies that have been sensitive to the ethnic dimension of Russian political processes have largely focused on processes of the construction of power verticals in the ethnic provinces of Russia and/or center-regional fiscal relations, with some exceptions (Herrera 2012, Yarlykapov 2013, Suleimanova 2018). In relation to identitarian politics only Russia’s gender issues are scrutinized a little better (Kondakov 2022). Few studies have touched upon racial diversity in Russia and racism, mostly approaching it from the angle of discrimination in law enforcement or by providing long historical overviews of the question of race in Russia over several centuries (Zakharov 2015, Avrutin 2022). In a recent piece in the journal Slavic Review, Marina Yusupova provides a powerful critique of the lacuna of studies of race in sociological research on Russia (Yusupova 2021).

Surprisingly, the various issues of diversity management in Russia have remained on the periphery of Russian studies even when discussing a unique structure of center-regional relations. Instead, in most of the relevant political science and sociological works, the country’s cultural and racial, though less so, spatial, homogeneity had been largely taken for granted. When scholars think of the country’s current geopolitical ambitions they think primarily about its Soviet and Imperial legacies while largely neglecting similar issues when considering the Kremlin’s present-day domestic politics towards the regions. The resulting paradox is that Russian studies have echoed the discourse of Russia’s political elites, which has systematically suppressed ethnic minority voices and concerns. European public discourse, too, has seen Russia as a homogeneous space without significant internal divisions that could matter. Moreover, the European public has taken the images of Moscow or/and St Petersburg — two capital cities — as images of Russia and its most significant realities, despite the popular saying that exists in Russia itself: “Moscow is not Russia”, meaning that the muscovites live their separate lifestyle that is very different from the lives of the rest of population. However, the domestic politics towards the provinces and Russia’s diversity management could tell a lot more about the reasons and possible consequences of the current war than the Kremlinology that has dominated Russian studies for too long.

The resulting paradox is that Russian studies have echoed the discourse of Russia’s political elites, which has systematically suppressed ethnic minority voices and concerns

Therefore, there is an urgent need for a greater focus on Russia’s multi-layered diversity and inequality from various standpoints. I highlight the necessity to consider the varieties of inequalities (social, cultural, spatial/regional, economic) and their possible overlaps. Here are my main recommendations:

1. Russia’s 80+ provinces should be studied at depth from an interdisciplinary perspective

Inequality in Russia, as elsewhere in the world, has a geographical dimension. In the words of Doreen Massey, the preeminent scholar of uneven economic development: ‘‘space matters’’ for welfare and wealth within countries, as much as between them. Electoral polls have recently shown that people have different political priorities based not just on whether they are from a center or periphery, but also depending on how their particular region has fared in the last decades. Despite the fraudulent elections, this is also relevant for Russia. Although it is widely believed that all revolutionary changes begin in the metropole and are usually made by a small group of people, there is much historical evidence suggesting that provinces matter too. In fact, in many countries significant political change started at the periphery. Therefore, ‘periphery’ — however we choose to interpret it, matters. The recent protests in Baymak confirm this thesis. Moreover, with the development of digital technologies, those usually silenced or passed over by elites in the center now have more opportunity to make their voices heard, even in countries like Russia. Current digitally mediated social movements by indigenous peoples against the war (“Buryats against the war”, “Kalmyks against the war” etc) are one of the examples of how previously suppressed voices can be heard today. However, most social research until recently was focused on the center — the two capitals — and overly narrow subjects of research, lacking consideration of the social and political life outside of a few well researched sites.

2. Local research agenda and local researchers should be supported on many levels

While it is argued that it is most important to know in depth what is going on around the political centers where the most important political decisions are made, because the rest of the population is only swallowing them, this is not always the case as argued above. However, there are more structural reasons for this emphasis on researching political centers. Often the best funded academic institutions in the country (especially in Eastern Europe) are located in capitals. Moreover, it is convenient to do field research in cities with well-developed infrastructure and in many ways too costly to choose less attractive research sites on the periphery. Another reason is deeply rooted in spatial-economic inequalities especially prominent in the post-Soviet space: it is highly difficult to get enough economic, human and academic resources to make local social sciences competitive with the standards of a capital, especially in such a territorially vast country as Russia. Local researchers not only have fewer opportunities but also less symbolic and cultural capital to obtain funding or lay claim to important outcomes for their research. Who cares what is going on in the periphery? Why is it important? Why should a funding body give money to a local researcher or research institution when it can give resources to a big name and get better media coverage? This is the Matthew effect in spatial terms — accumulated advantage. Therefore, it is important to support academics who do research on the Russian regions and related questions, as well as social scholars originally from the regions, especially those who are currently based there. The latter is especially important because there is another lack in current research on Russia: there are barely any critical approaches to social relations and discourses that dominate in Russian society. For critical approaches to proliferate it is important to give voices and space to those who are silenced and less resourced.

3. Promotion and legitimation of critical approaches to understanding of Russian society

Critical approaches that are inherently interdisciplinary are gaining momentum in the West because of growing inequality within societies that lead to the spread of populist and nationalist politics. However, as already mentioned, there is a lack of such approaches in research on contemporary Russia. Critical research always highlights inequalities while at the same time claiming that there is no objective truth because each focus depends on the vantage point where the researcher stands. Therefore, it is important to give voice to marginalized and most disadvantaged researchers from the peripheries and provincial research institutions, which is not the case in the field of Russian studies.

We have seen Russia as homogeneous not just because an overemphasis on the capitals, but also because there are academic inequalities that shape our persepctives: voices from the capitals are most heard, most visible, most loud, and most widespread, while voices from the peripheries are rarely get published or receive wide audience otherwise. Postcolonial and decolonial critical perspectives accentuate the epistemological inequalities that the division between metropolitan academia and colonial knowledge creates. This is an important problem that needs to be addressed. Indeed, former or current colonies have the right to create their own scientific language and epistemologies; this is necessary and beneficial for all of us because it diversifies and challenges our understanding of reality. However, it is even more important to acknowledge academic inequalities in access to Western knowledge production and opportunities for research impact, despite one can view it as colonial in nature. It is important to acknowledge that academic voices from the Russian provinces have many more obstacles and much fewer resources to present their findings to the Western audience and policy makers as well as to conduct research, because of the centralization of resources happening in all spheres in Russia, including academic knowledge production. Undoubtedly, there are big names from Russian regions known in the West and in Moscow, however, considering how big Russia is, their number is too small and the greater promotion of local researchers, their agenda and voices are needed.

We have seen Russia as homogeneous not just because an overemphasis on the capitals, but also because there are academic inequalities that shape our persepctives

4. Greater emphasis on the impact of the Soviet and Imperial past on present transnational and translocal relations

Research on contemporary transnational links in the area and the lasting impact of the Soviet and Imperial legacy is also important. While most studies currently focus on violent ethnic conflicts and international security in the region (George, Julie A 2009), there is still lack of studies of how the soviet and imperial legacy currently impacts domestic politics, environmental issues, diversity management and everyday relations between people, including but not limited to racial attitudes and inter-ethnic communication. The two most recent migration waves after the start of the Russia-Ukraine war are especially relevant in this regard. How do Russian citizens choose where to settle to avoid passive regime support, economic crackdown or to wait out the conscription to the war? What is the role of previous kinship ties, tourist experience or business relations? How do former subjects of racist attitudes experienced in the former metropole welcome the newcomers on their own land? How will the most recent migration waves change politics, policies and transnational ties in the region? These and other relevant issues should be studied from various perspectives, first of all, from the perspective of the receiving countries themselves, but also from the perspective of the sending country and globalization more broadly. The consequences of Ukrainian and Russian migration from the war have just started to appear, but they will have a continuous impact on the further transformation of the post-Soviet space and the whole world. Because of the changing nature of world development aimed at high technology and resistance to climate change, it is crucial to conduct research both on business and human relations in this regard and avoid limiting the focus on top-down international politics. Complex Soviet and Imperial legacy manifests itself in many ways, not just in newly independent post-Soviet states but also in Russia itself, creating entangled relations between the center, the provinces, and the neighboring states. These relations can be fruitfully addressed through the prism of border or transnational studies as well as memory politics and of course migration studies.

5. Communication of local knowledge and knowledge on local issues to wider audiences

Importantly, many issues linked to diversity and inequality in Russia are securitised. For example, exploring everyday manifestation of ethnicity in a state under authoritarian rule, where the very existence of indigenous ethnic minorities that constitute subnations is considered a challenge to the integrity of the country, makes research on ethnic diversity a sensitive topic. Similarly, migrant laborers, often Muslims, are frequently accused by the regime as one of the “enemies” of the state. This is a strategy for legitimizing increasing securitization as the state presents itself as a protector of the people from external dangers such as terrorism and Islamization, which are seen as threats in predominantly non-Muslim societies. Such topics remain both under-researched and less communicated to a wider audience due to their potentially “extremist” nature that both researchers and journalists tend to avoid. Currently proliferating social movements in favor of the re-federalization of Russia is another such issue. The same can be said about local protest activities or ecological issues that tend to be hidden from the national media agenda in Russia, because it is easier to repress them in smaller localities. Moreover, the same logic of centralization of resources in academia applies to media news production and as a consequence the broader audience knows less about endeavors in Russian provinces. While this is a problem in other countries too, in Russia it is exaggerated by the authoritarian nature of the state and specifics of center-regions relations. Therefore, it is important to establish links between scholarly and journalistic communities for a greater impact of Russian studies on policy development and public knowledge of Russia and the post-Soviet space more broadly. The promotion of local history, environmental issues, and urban and rural developments to the wider audience is an important factor for future democratization.

Conclusion

A new mapping of the future of Russian studies with an intra-regional focus is sorely needed for advancing high-quality research in such a vast multi-ethnic state as Russia. The main reasons for such direction are:

- Growing economic inequality results in the overemphasis of the agenda of social research relevant to the capital cities and in the lack of due attention to provinces and the periphery. In turn this leads to an uneven distribution of public and scholarly attention to particular issues and ignoring others, thus leaving many blind spots which can explain important social phenomena. This is especially important for multi-ethnic federations.

- Authoritarian regimes affect the global world, not only by their direct interventions into the domestic politics of their neighbors and other countries, but also by unintended consequences of their lack of attention to climate change, poor ecological policies and other issues. These and other societal problems are more relevant for the peripheries of authoritarian countries than their capitals, therefore many such issues are ignored or stay silent.

- Most social research on authoritarian countries focuses on top-down politics, therefore it rarely pays attention to bottom-up potential for democratization, which is at the core of any democratization process. Although there is some research on protest activism, it is not the only way to build horizontal ties that could lead to social solidarity and, as a consequence, to political and societal change. By paying attention to developments on the peripheries and what unites them besides the political centers, we facilitate this change.

We believe that a more equal distribution of academic attention from the center to peripheries and from top-down politics to bottom-up social developments will help to bring about a new political agenda that can eventually result in a significant social change.

Thus, by promoting aforementioned approaches, topics and methodologies we will be able to observe Russia’s multi-layered diversity in all its complexity and beauty and will have deeper knowledge of this vast and increasingly heterogeneous country. This is much needed in any possible scenario of the future: whetherl Russia disintegrates as a result of the failure in the war or not, its regional complexity and social diversity more broadly will matter in the near future much more than ambitions of any mindless dictator. By facilitating research on diversity and inequality we will inherently advance democratic agenda for society.

Bibliography

Avrutin, E. M. 2022. “Racism in Modern Russia: From the Romanovs to Putin”. (Russian Shorts). Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350097308

Frye, T. 2019. Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia. Princeton University Press.

George, Julie A. "Expecting ethnic conflict: the Soviet legacy and ethnic politics in the Caucasus and Central Asia." In The politics of transition in Central Asia and the Caucasus, pp. 75-102. Routledge, 2009.

Goode, J. 2016. “Love for the Motherland (or Why Cheese is More Patriotic than Crimea). Russian Politics, 1(4), 418-449. https://doi.org/10.1163/2451-8921-00104005

Gorenburg, D. 2003. “Nationalism for the Masses: Minority Ethnic Mobilization in the Russian Federation”. Cambridge University Press, 2003

Greene S., Robertson G. (2020) Putin v. the People: The Perilous Politics of a Divided Russia. Yale University Press.

Hale, H. E. 2014. Patronal Politics: Eurasian Regime Dynamics in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hakim, R. 2007. “Terinitsii Put k Svobode (Sochineniia. 1989–2006” [The Thorny Way toFreedom. Essays. 1989–2006]. Kazan: Tatarskoe Knizhnoe Izdatelstvo.

Laruelle, M. 2009. “In the Name of the Nation: Nationalism and Politics in Contemporary Russia”. Palgrave MacmillanLaruelle, Marlene. 2021. “Is Russia Fascist? : Unravelling Propaganda East and West”. Cornell University Press, 2021

Sharafutdinova, G.2020. “The Red Mirror: Putin’s Leadership and Russia’s Insecure Identity”. Oxford University Press

Giuliano, E. 2011. “Constructing Grievance: Ethnic Nationalism in Russia’s Republics”. Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London.

Kondakov, A. 2020. “The Queer Epistemologies: Challenges to the modes of knowing about sexuality in Russia”. In Z. Davy, A. C. Santos, C. Bertone, R. Thoreson, & S. E. Wieringa (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Global Sexualities (Vol. 1, pp. 82-98). Sage.

Kolstø, P. and Blakkisrud, H. (eds). 2016. “The New Russian Nationalism: Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism 2000–15”. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press: 288.

Lumsden K. 2013. “‘You Are What You Research’: Researcher Partisanship and the Sociology of the Underdog.”Qualitative Research 13(1): 3–18.

Prina, F. 2021. ‘Constructing Ethnic Diversity as a Security Threat: What it Means to Russia’s Minorities’, International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 28, 1.

Suleymanova, D. 2018. Between regionalisation and centralisation: The implications of Russian education reforms for schooling in Tatarstan. Europe-Asia Studies, 70(1), 53–74

Verhovsky A., Pain E. 2013. “ Civilizacionnyj nacionalism: Rossijskaja versija “osobogo puti”” [Civilizational nationalism: a Russian version of a ‘special path’]. Politicheskaja konceptologija: zhurnal mezhdisciplinarnyh issledovanij [Political conceptology: a journal of interdisciplinary studies]. Pp. 23-46

Yarlykapov A. 2013. “Polijetnichnyj Dagestan: edinstvo v mnogoobrazii” [Multi-ethnic Dagestan: unity in diversity] in Politika I Obschestvo. [Politics and Society], Vol. 5 (101) pp. 568- 574.

Yusupova, G. 2019. “Exploring Sensitive Topics in an Authoritarian Context: An Insider Perspective”, Social Science Quarterly, 100, 4.

Yusupova, M. 2021. “The Invisibility of Race in Sociological Research on Contemporary Russia: A Decolonial Intervention”. Slavic Review, 80(2), 224-233. doi: 10.1017/slr.2021.77

Yusupova M. 2022. “Coloniality of Gender and Knowledge: Rethinking Russian Masculinities in Light of Postcolonial and Decolonial Critiques”. Sociology. July 2022.

Zakharov .2015. Race and Racism in Russia. Springer. 233 p