A Glimpse of the True Face of War – World War I

I am from a country shattered by war. My childhood was spent surrounded by Azerbaijani refugees who had fled from Karabakh, Lachin, and Armenia. I still remember the poverty of the early 2000s. The Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, which broke out in 1987, affected every person living in this region. Because my mother was a war correspondent in Karabakh war, she chose to work as a teacher at a refugee school. That’s why I also spent eight years studying at a refugee school. Most of my school years were spent in an former cowhouse building with broken windows. Concepts like laboratories or reading rooms were as distant to us as Mars. I never liked history class at school—it felt boring. The only things I can recall from those years are names like the Stone Age, Bronze Age, Atropatena, Albania, Manna, Ancient Egypt, and Ancient Greece.

My general problem is this: if I can’t connect the knowledge I learn to the present day, I struggle to understand it or remember it. I found war topics in history books especially dull. One side attacks, the other either wins or loses—always told without emotion. As if robots were fighting. I’m not sure whether the problem was with the way history was taught or with me, but I didn’t fully grasp what war truly meant until 2020.

I come from a veteran family. My mother is a war correspondent, and my father is a war veteran. I’ve also been surrounded by many Azerbaijani IDPs and refugees. Yet I only truly felt the fear, horror, sorrow—and even joy—that war brings during the Armenia-Azerbaijan war in 2020. Until then, to be honest, I was quite unaware of the wars happening in other parts of the world. I was a pretty apolitical person. I knew who the president of Azerbaijan was, but I couldn’t name the leaders of other countries. I never watched the news. I didn’t even know about the Abkhazia issue in Georgia. Out of ignorance, I once tried to cross into Azerbaijan via Abkhazia from Russia. At the Russia–Abkhazia border, they told me I couldn’t go through. I first learned about the Chechen War through the Chechen refugee children who studied at a refugee school in Azerbaijan. They visited another refugee school where my mother was working at the time. What I mean is—I was someone completely disconnected from world news.

The war in 2020 changed me deeply. Now, I can genuinely feel the pain of people living in Sudan, Myanmar, Ukraine, Yemen, and Gaza. Not only civilians—but also the Russian or Ukrainian soldiers who were forced to go to war. The only thing I can do is sit in front of a computer and write. To learn about wars and tell others how terrifying they truly are. I’m not a great writer. I don’t even have an audience. But this is what I can do right now.

Recently, I bought a book about World War I that was on sale. While reading, I notted down some quotes for myself. I found them meaningful and thought I’d share a few.

World War I…

Back in 2015–2016, while hitchhiking from Germany to France, I could move freely across Schengen countries. No walls, no barbed wire. Yet between 1914 and 1918, those same lands had turned into a graveyard. A bloody lake where millions of soldiers died, some without even the chance to be buried.

This quote from the book captures just a fraction of war’s horror:

The horror and brutality of war often inflicts mental trauma and anguish upon the men who fight it. The sheer scale of World War I and its static trench nature ensured that mental casualties would be at an all-time high. The term 'shell shock' was used to describe psychiatric battle casualties, whose symptoms ranged from paralysis, to aimless wandering, to loss of bladder and bowel control. During the war, losses due to mental illness were, staggering. The United States sent nearly two million men to Europe in World War 1. Of this number 116,516 were killed, and another 159,000 soldiers put out of action due to psychiatric problems. Psychiatrists on both sides of the conflict struggled to determine the cause of the mounting problems. Their answer was that the concussion of exploding shells somehow compressed the brain, resulting in a seemingly mental reaction. Some soldiers received care for their 'shell shock'; the Austrian Army even employed electric shock treatment as a possible cure. Other soldiers had their symptoms ignored, or were put to death for dereliction of duty. In truth, these men had just seen more death and slaughter than their minds could take. Wilfred Owen, a sensitive observer of war, understood this fact and expressed it in his poem 'Mental Cases':

These are men whose minds the

Dead have ravished.

Memory fingers in their hair of murders,

Multitudinous murders they once witnessed.

When you dehumanize a person—it becomes easier to kill him or her. Once you devalue any group to something less than human—a terrorist organization, the citizens of an enemy nation, members of a political party you dislike—you might even find yourself justifying their complete annihilation. But what we often forget is this: we all belong to the human race. We are all ordinary people— who play games on their phones while sitting on the toilet, get scolded by their mothers, procrastinate on assignments, gossip about neighbors, and send “good night” texts to their partners. How did we come to hate each other so much?

The famous Christmas Truce of World War I was one of those rare moments when this hatred paused, even if just for a short while. It didn’t happen on every front, and it didn’t last long—but it planted, however briefly, a seed of hope in humanity.

THE CHRISTMAS TRUCE…

As Christmas approached on the British sector of the Western Front, the weather turned clear and cold. Huddled in their trenches, the combatants — British and German alike — readied themselves for their first Christmas in the trenches. Late at night on 24 December, lighted Christmas trees began to appear in the German trenches. Men on both sides began to sing Christmas carols, and were stunned to find their enemies, dug in only a short distance away, joining in to sing the familiar songs. When morning came, nobody fired, lending the dawn an eerie calm. Men from both sides began to emerge from their trenches under flags of truce and made their way across No-Man’s-Land to meet the enemy. All across the line fraternisation broke out among men who had recently been trying desperately to kill one another. Germans and British shook hands, exchanged gifts, sang songs, played football, took photographs and buried the dead.

In some areas of the front, the Christmas truce never took hold, but in many areas it lasted for up to three days. It ended only when astounded officers ordered their men to recommence hostilities. Often the firing began again only after warnings and apologies were issued to the enemy. In the end, the Christmas truce did not hold and would not be repeated as the ferocity of the war grew apace. But for one brief moment, the common men in the trenches had bridged a growing gap of hatred to recognise each other’s humanity.

I mentioned earlier that I experienced the fear, horror, sorrow—and even joy—of war during the 2020 Armenia-Azerbaijan war. But joy in war? How can that be?! Is it the joy of being on the winning side? I don’t believe there is such a thing as a winner in war. Anyone who goes to war has already lost. There is no victory where there is death. So what, then, was that joy?

It was the joy of the war being over.

The joy of not hearing about more deaths.

The joy of no longer refreshing Telegram and Twitter every minute, to know, “Did they attack again?”

The joy of finally being able to sleep without wondering if a bomb would fall on me during the night.

I felt that joy on the final day of the 2020 Armenia-Azerbaijan war. I would no longer be jolted awake by any sudden sound in the middle of the night, anxiously checking the news.

But I couldn’t hold onto that joy alone for long. Just as the ceasefire was signed, an explosion occurred—not at the front line, but very close to where I lived, in Baku. An airstrike. It didn’t make much noise in the official media, but for those of us living there, it was undeniable. The joy of war ending clashed with the fear of an air raid on my own land, and the shock of both events happening at once. It was a cocktail of feelings, which made for me and for us .

No matter how many years go by, some truths about war never change. One of them is the joy that comes with its end. That joy was true for World War I as well. I believe in that truth, even if I can’t prove it.

People greeted the end of the war with enthusiasm, but it was a joy tempered with sorrow. The first modern, industrial war had ripped Europe asunder and slaughtered nearly an entire generation of the best and brightest. Nearly everyone, it seems, had lost a family member or friend to the fighting, thus Europe grieved in the wake of a calamity of nearly unbelievable proportions. One English woman, mourning the loss of her beloved brother wrote,

“Five foot ten of a beautiful young Englishman under French soil. Never a joke, never a look, never a word more to add to my store of memories. The book is shut up for ever and as the years pass I shall remember less and less, till he becomes a vague personality; a stereotyped photograph.”

The aftermath of the killing can still be seen across Europe today. Nearly every English village or French town contains a memorial to the fallen, a memorial that family members still visit and adorn with flowers.

All along the front lines, German, French, British and American troops came out of their trenches to meet each other. There were handshakes all around and the exchange of souvenirs, pictures and addresses. Although some soldiers actively hated their enemy, most respected him as a worthy adversary who had suffered through a common hell. Victors and vanquished alike met as friends on that day.

“Then a quite startling thing occurred. The skyline of the crest ahead of them grew suddenly populous with dancing soldiers and down the slope, all the way to the barbed wire, straight for the Americans, came the German troops. They came with outstretched hands, ear-to-ear grins and souvenirs to swap for cigarettes… They came to tell how glad they were [that] the fight had stopped, how glad they were [that] the Kaiser had departed for parts unknown, how fine it was to know that they would have a republic at last in Germany.”

From Paris to London and Washington, wild, spontaneous celebrations broke out in the streets when news came of the armistice. Soldiers were greeted with great joy as saviours of the world. However, in many capitals from Berlin to St Petersburg, there was no joy, only continuing revolution and hardship. The war had come to an end, and while the victors celebrated with an enthusiasm not seen since 1914, it became apparent to many that there was much left to be accomplished before the world would truly be at peace.

A British soldier, learning of the armistice, wrote of what peace meant to him:

“No more slaughter, no more maiming, no more mud and blood, and no more killing and disemboweling of horses and mules — which was what I found most difficult to bear. No more of those hopeless dawns with the rain chilling the spirits, no more crouching in inadequate dugouts scooped out of trench walls, no more dodging of sniper’s bullets, no more of that terrible shell-fire. No more shoveling up bits of men’s bodies and dumping them into sandbags, no more cries of 'Stretcher-bear-ERSI, and no more of those beastly gas-masks and the odious-smell of pear-drops which was deadly to the lungs, and no more writing of those dreadfully difficult letters to the next-of-kin of the dead.”

Of course, that joy is also one of the most fleeting emotions. The war may be over… but now people are left alone with the graves and memories of their loved ones. Or perhaps there isn’t even a grave of their beloved one.

If, for a French soldier, the greatest enemy was a German, for a German child, that man was simply “father.” For a French woman, that soldier might have only been “husband.”

Our hatred toward that person does nothing to ease the grief of those who loved them.

The cemeteries near the battlefields tell their own stories. The American cemeteries are massive, moving places reflecting the American choice to bury all of the fallen together in one place, aiding in a family’s efforts to visit their fallen loved one. The gleaming white crosses seem to march off into the distance in eternal formation. German cemeteries are dark, brooding affairs. The crosses are dark brown and the statuary seems to reflect a torture not seen in cemeteries reserved for victors. British cemeteries are altogether different. The British chose to bury men near to where they fell, meaning that many of the cemeteries are quite small. In addition the British chose to make their cemeteries closely resemble an English garden, with roses blooming everywhere as a touching, final reminder of home. British cemeteries also contain a moving individuality, for the families of loved ones were allowed to add a special inscription on each headstone. The grave of V.J. Strudwick, who was only 15 when he died in 1916, reads 'Not gone from memory, nor from love.'

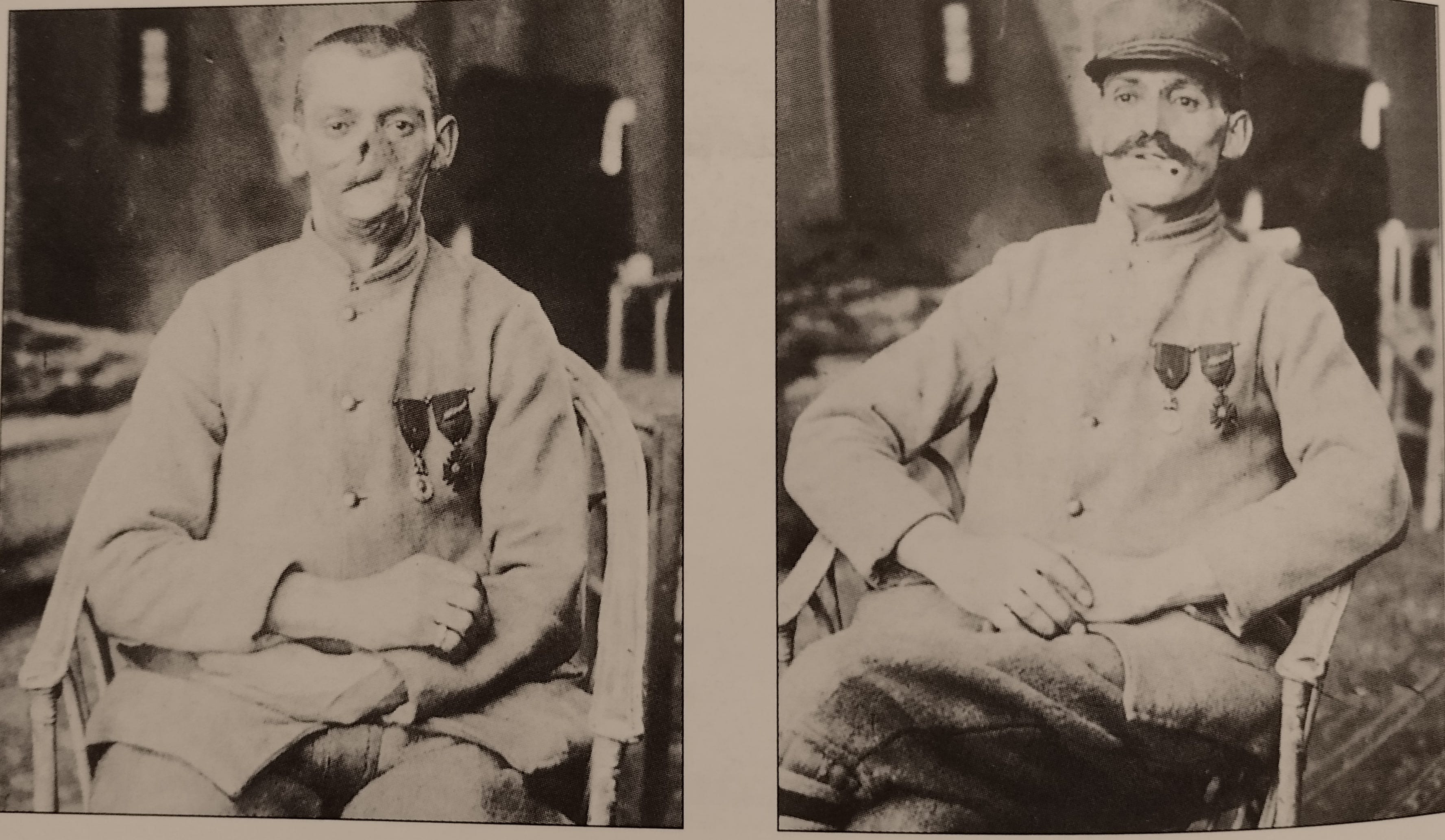

The cost of the war in terms of lives, as illustrated by cemeteries and memorials, was staggering. Nearly 15 million people, soldier and civilian alike, perished in the cataclysm. That simple number does not indicate the true level of wartime loss and grief. Each soldier lost represents parents and grandparents stricken by loss. Wives and children were crushed by the death of a husband and father. The lives that were cut short by the war affected hundreds of millions of people across the world, leaving many with a sense of futility and frustration. In addition, nearly 30 million soldiers returned from World War I having been wounded, some seven million of whom were permanently disabled. Although advances in medicine had kept many wounded soldiers alive, medicine often could not repair faces and limbs that had been ripped apart by shrapnel. Thus many veterans, although not considered disabled, lived the remainder of their lives as ghastly reminders of the horror of war. Finally the war resulted in innumerable cases of psychological wounding. The brutality of the trenches and the terror of battle often overwhelmed the minds of combatants, leaving strong men scarred forever. The world now recognises the perils of post-traumatic stress disorder, but the World War I era did not. Brave men were forced to wander through the remainder of their lives in a mental hell which nobody understood but them.

The last time I was in Europe was in 2016. I remember it as a area covered in forests, with beautiful rivers and a peaceful nature that brought a sense of calm. I don’t know when I’ll be able to go again, but now, whenever I walk those lands, World War I will always come to mind. This time, I’d like to visit the cemeteries and memorials that bear the marks of war. I hope to see the Somme region in France, and the city of Ypres in Belgium, which reborn from its ashes.

Then, I’d like to continue on a Balkan tour and continue on to Çanakkale and Sarıkamış. In this way, I want to feel World War I not just through books, but through the soil soaked with the blood of mostly young men.

NOTE — All quotes and images are from Andrew Wiest’s The Illustrated History of World War I.