Constant Translation of Reality: How Artists in Exile Seek a New Identity

Last year, artists and industry experts interested in technology gathered for the international laboratory Pause/Play: Culture under Pressure. As a result of the lab an exhibition Translating Transition took place in Yerevan becoming an extension of the project and an opportunity for the participants to apply the acquired knowledge in practice. Curator and mentor of the exhibition Anna Titovets spoke about tools that helped artists to analyze and reflect the new reality, how the project participants "translated" their experiences into the language of another culture, and why it is impossible to draw a line between those who left and those who stayed.

— Anna, this year’s project Pause/Play: Culture under Pressure covered the problems of using digital technologies in art. This is quite a broad topic. What specific issues did the participants of the project in Yerevan focus on and what was discussed during the conferences, lectures, presentations?

— The program had several directions. It was a multi-faceted experience for the participants. On the one hand, as you’ve pointed out, we touched upon the use of technology by artists and cultural actors. Through a two-month online program, we introduced participants to the ways of how different tools can be used — from AI to using digital and internet technologies in activism.

Moreover, the program had a specific mission. We wanted to cover topics related to decolonial practices, to the integration of people who had to leave their countries for geopolitical reasons, censorship and wars. It was a large block of issues that were addressed both indirectly and directly. We talked to participants about issues related to integration, rethinking one’s own identity in a new context. There was a lot of talk about how to be attentive to local communities, local culture, and to find a way that would allow everyone to be in peaceful and productive coexistence without losing one’s cultural identity.

— This is a very broad selection of topics. Even two months is not enough to deal with all of them.

— Yes, that is true. In my opinion, this is both the strength and the challenge of the program. The organizers wanted to touch upon all these important and sometimes painful issues. At the same time, there is a practical component. I wanted the program to take place not only in the field of theories and intellectual constructions, but also to give the participants practical tools that would help them in this new life. We gave the participants these tools, but did not insist on its application, because the integration of tools and artwork can only happen on a personal level.

— One of the goals of the project was to show artists how to use virtual reality, blockchain, artificial intelligence and other tools to accomplish artistic goals. How exactly can this help artists who have been forced to leave their home country due to political repression?

— It is, of course, the challenge for each of the artists to figure out how to apply these tools in a way that their expression will benefit in some way from the use of technology. I always tell my students: it’s very important to remember that if your statement doesn’t require the use of all these wonderful new technologies, don’t torture yourself. Technology is just a tool. We live in a modern world where everyone is using new technology, and it provides opportunities that didn’t exist before. However it doesn’t always work for every case in terms of framing the idea and bringing it to the end user. Very often artists do not have confidence and experience in the capabilities of different technologies. Our task was to familiarize them with it and show them how it is used in culture and art.

— What projects did you tell the participants about? What examples did you give?

— For example, we were talking about The Electronic Disturbance Theater, who were essentially the first hacker-activists in the art field. Through artistically designed cyberattacks, they drew attention to social injustice and warfare. Moreover, I gave an example of an anti-war movie/video art that was created by the art group Pseudo-Marxist Media Partisans. The project is made in the space of a game similar to GTA. The movie talks about the logic and philosophy of war in game and real space and is a reflection on the theme of desertion.

Another one of my favorite examples is the project of the group! Mediengruppe Bitnik "Parcel for Julian Assange". In January 2013, they sent a parcel to Julian Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy in London. The parcel contained a mini camera that documented its journey through Britain’s Royal Mail through a small hole made in the box. The journey could be followed by anyone on a website. Artists wanted to see if the package could reach Assange. After about 32 hours it reached its destination, and several thousand people witnessed Assange himself opening it and addressing the public.

— Translating Transition exhibition in Yerevan was the culmination of the project. What was the concept of the exhibition?

— It is difficult to talk about the concept, because it is not an ordinary exhibition project. Usually the curator has a concept, an idea, and according to it he or she forms the composition of the projects participating in the exhibition. In this case it was the other way around. We offered all the participants of the laboratory to make their own art projects and showcase them at the final exhibition. We did not choose a specific theme, but the range of topics was supposed to mirror the program.

Initially, we wanted to include only the projects created by the last year’s participants. However, it quickly became clear that this is actually a good and useful practice for this year’s participants. They could implement their projects right during the program. Together with the mentors, we helped shape these statements into a final artwork. It was not an exhibition in the common sense of the word but rather an improvisational continuation of our laboratory.

— What was it like to curate an exhibition and analyze the experience of completely different people who found themselves in similar circumstances?

— The curatorial work, apart from helping artists find a form and formulate ideas, was to find the most "workable" solution for the arrangement of the projects in one space. They had to create a coherent narrative for the viewer. This is very important.

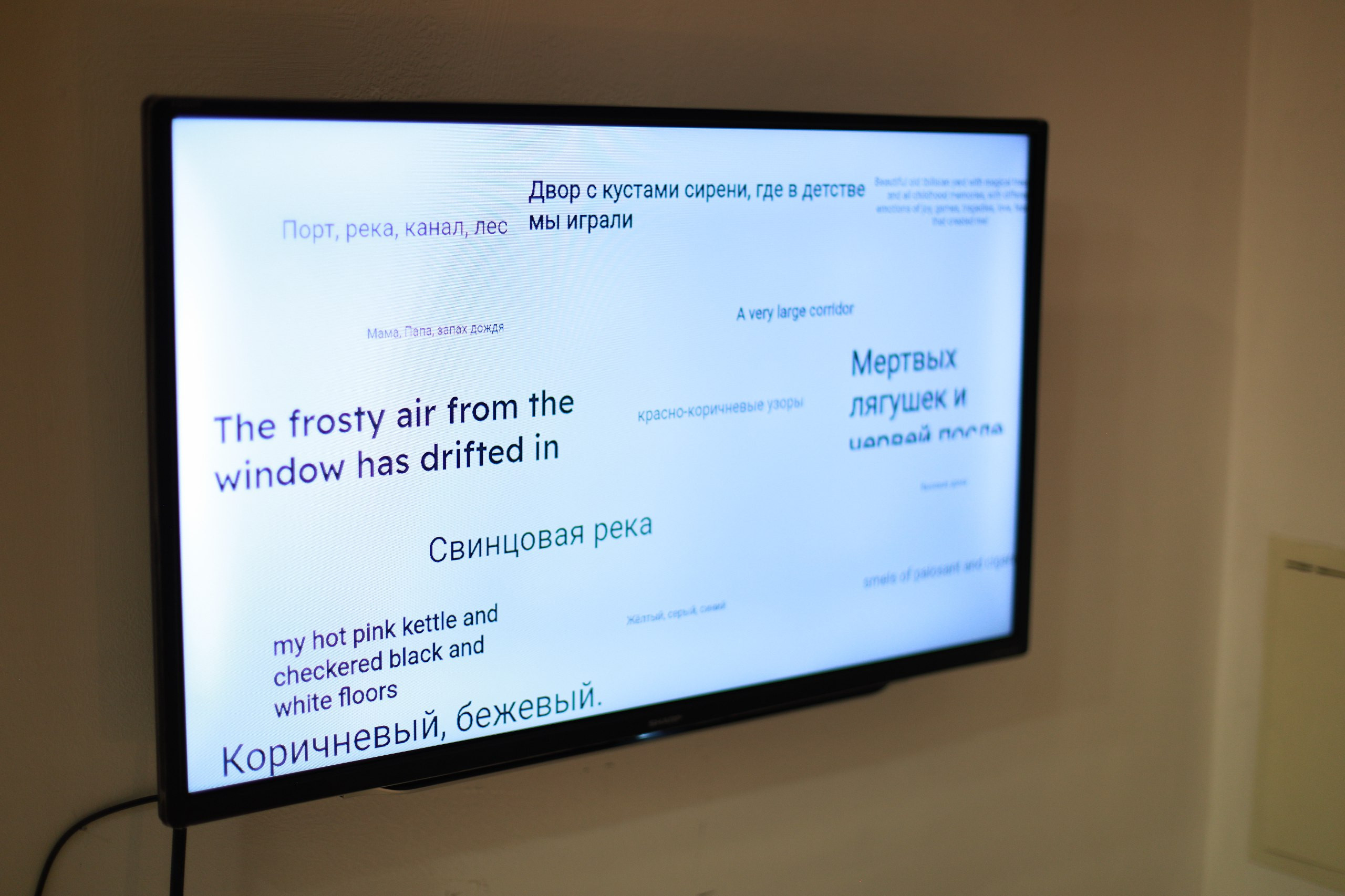

I think the name Translating Transition is quite apt because, on the one hand, it can have different interpretations. On the other hand, it reflects the complexity of experiences and problems that every participant, every immigrant faces. Each of the participants is in some kind of "transition period". The word "translating" reflects the need to constantly "translate" the reality in which you find yourself, not only literary, but also to translate the language of a new culture, everyday life, habits, social structure in a new place. Immigrants are in a state of constant translation of reality, of new circumstances. Each project presented at the exhibition reflected on these topics in one way or another.

— If I understood correctly, at the exhibition the artists tried to create a new language, a new cultural semiosphere that could reflect their immigrant experience, understand their otherness and analyze the process of integration into new social structures. How did the participants in the exhibition interpret these questions?

— It is peculiar that this year’s projects were activist in their nature, but rather focused on people’s inner experience. I think that last year there was much more activist fervor, an attempt to influence reality. But the war doesn’t stop and new wars are breaking out. A lot of people have accumulated fatigue, a personal, inward-looking experience. At the exhibition, one can notice that most artists often address deeply personal experiences.

For example, the work of the Ukrainian participant Oleksiy Chumak (collaboration with Olya Makhno) Miscarriage. It is a video-art, documentation of a performance dedicated to the trauma of experiencing the tragedy of war. The artist compares his sensations with dead whales or seaweed washed away on the shore, reflects on the complexity of integration in a new "ecosystem" and how it is possible to revive the trauma of the past.

The exhibition also featured the rather lyrical Vishapagorg project by artists Gray Cake, Katya Pryanik and Sasha Serichenko. They immigrated to Armenia and met Anna Ghazaryan, a woman who professionally weaves carpets and tapestries with traditional patterns. Katya decided to learn this art, introducing herself to the local culture through her fingertips. The name of the project "Vishapagorg" means "Dragon Carpet". It is the oldest surviving Armenian carpet. It depicts some of the most common patterns found in traditional culture. Using these patterns as a starting point, the artists selected a dataset (database) of carpets and tapestries and created a new interpretation of these patterns in a video art format with the help of Ai. It brought different contexts and technologies together.

otar (Narek Bunatyan), an artist from Armenia, made a sound-art work ան.ժամանակ / time: less, in which he collected folk melodies of oppressed people from Armenia, Georgia, Ukraine and Palestine. The artist processes and samples these melodies in a special way, showing, on the one hand, the similarity of cultures and, on the other hand, revealing the individuality of each culture. By weaving the melodies of these different countries into one work, the artist creates a field of reconciliation and gives hope for a peaceful future.

The exhibition also featured several works that were analyzing the topic of dreams. The artist Evgenia Rzheznikova analyzed dreams of people who were subjected to political repression or lived in totalitarian society. She analyzed three historical periods: the Second World War, the Soviet period and modern Russia. At the same time Diana Meyerhold and Anastasia Marochkina made a project in the metaverse with the possibility of using augmented reality, in which you can listen to the dreams of people experiencing the war.

— Were there any projects at the exhibition that still focused more on the public experience rather than the personal?

— One of the strongest projects, in my opinion, was dedicated to the lives of documents of men who were involved in the war. Maria Filippova’s photo project "Everyday Life of Military Documents" explored the connections between war, militarism and masculinity in the context of increasing militarization of society. Three different stories of men are shown through photographs of documents that determine their fate in a wartime setting. "Crusts" and bureaucratic documents become artifacts that reflect the intertwining of the ideological machine and human life.

— I think the issues raised by the artists in the exhibition are very well understood by the immigrant community, which has grown tremendously in the last few years, but how applicable is this experience in a broader global context? Can this exhibition be relevant to those who did not leave but stayed?

— In my opinion, this program does not have the goal to appeal to those who have stayed. Moreover, as someone who had not yet moved from Russia at the time of the exhibition, I am very upset when a divide is drawn between those who have left and those who have stayed. It’s not very fair. For example, many of those who stayed behind went into internal migration. They have the same worries, problems with self-identity and getting used to a new reality. Nevertheless, the exhibition was held in Yerevan, so it is obvious that it was not organized for those who stayed in Russia. And yet, the exhibition operates with universal ideas.

Of course, people who didn’t go through immigration wouldn’t understand it with the depth of pain and experience of those who have gone through it. But at the same time, tragedies that are discussed in one way or another are relevant to a different audience. It is a fixation of the moment. I think such exhibitions help to establish a dialogue with different cultures and find a path that could lead us to peaceful coexistence.

Photos: Project Pause/Play: Culture under Pressure / Kulturschafft e.V. / Goethe-Institut / Narek Dallakyan / Daniil Primak