Anna Li: The Edge of Sexuality

By Roman Shalganov, Yana Sidorkina

Translated by Anna Pantuyeva

In a fashionable contemporary art gallery in the center of Moscow, visitors leisurely take in the high-brow themes and narratives addressed by the artworks they are viewing: postcolonialism, the deconstruction of Russian imperial discourse, community rights, among others. They linger at an exhibition wall that appears strangely bare. But three small paper sheets hang on the wall, two of which contain photographic reproductions of artworks, and the third containing a text. The text explains that the works that were to be shown here have been detained by Russian customs officials at the Russian-Ukrainian border. Clearly, the artist’s work has broached the imaginary boundaries separating the political, the artistic, and exhibition practice.

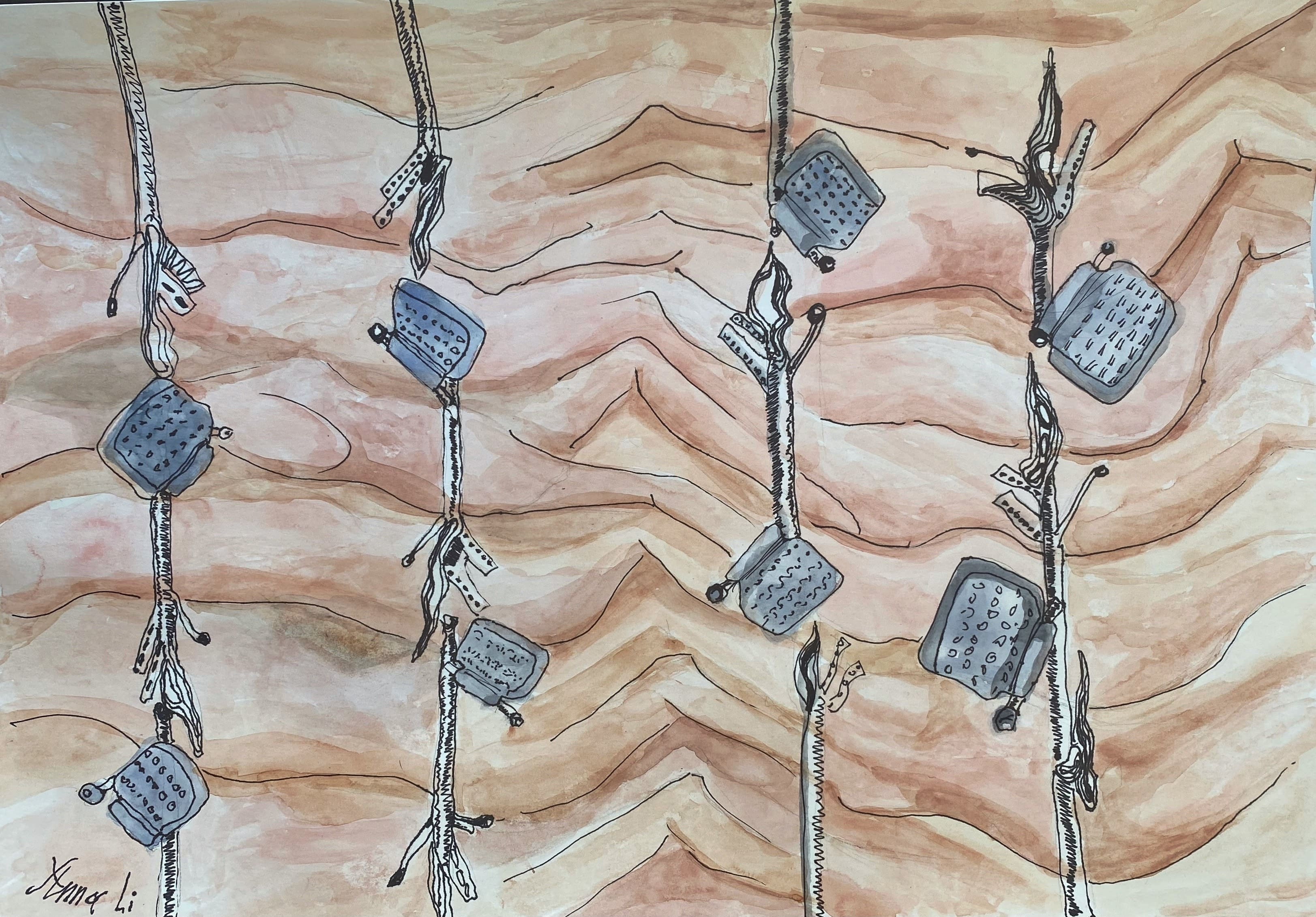

The two missing works were eventually released by customs and delivered to the exhibition. They are two paintings, each featuring a lilac dusk pierced by the lines of an illuminated staircase. Each staircase is divided into three sections. The vertical lines of light, which upon closer inspection turn out to be streams of rain, draw the viewer’s eye to the bottom of the staircase. There, their attention is brought to several human figures, descending and ascending and rendered in grey tones. The painting on the left features a human figure in a wheelchair as its narrative focus. The painting on the right depicts the same figure, but with kind pedestrians supporting the person in the chair after having helped them down the stairs.

The artist conveys the theme of compassion by rendering the human figures in a rather abstracted fashion—we cannot guess their gender or age, nor social position. We do sense, however, their significant presence conveys mutual caring. The two works serve to pose a question of difference: what does it mean to be different and not belong to the majority? How do human collectives define difference? And how do they interact with those whom they mark as the other? The artworks do not give straight answers to these questions, but they proffer possible solutions to the problem for both sides—for the crowd/majority and the other. Political thinking is lurking in these semi-abstract works.

The paintings’ statements register deeper when we learn that the person in the wheelchair is the artist herself. This is Anna Li, nom de plume of Anna Litvinova, a 27-year-old artist who lives and works in the Ukrainian city of Odesa. Litvinova was born with spinal-muscular dystrophy and often paints or draws reclined. To reach the canvas while lying, she assembles several paintbrushes together to form a long handle, or sometimes asks for assistance to have the canvas placed closer to her or even to turn it upside down. She calls herself a human-transformer, as she takes her wheelchair as an extension of her body, and has three titanium bolts in her spine. Anna took to painting and drawing at the age of ten and has been practicing studio art ever since. She became interested in contemporary art only three years ago, an interest that brought her to Sreda Obuchenia, an online art school, based in Moscow, and later to a higher-educational institution named Baza (the base). As Anna herself explains, at some point she understood that she wanted to pursue art practice professionally. And people with special needs, whose bodies and lives are different from those of the abled majority, became the main interest and focus of her work.

In her artistic practice, Anna explores not only the boundaries between physical and social bodies, but also those running through such bodies. Case in point, in addition to painting, Anna practices photography. In her photographs, she problematizes human sexuality as a cultural construct, with a particular interest in the objectifying power of the male gaze and how the male gaze reinforces a narrow, limited view of masculinity. Such an inquiry is particularly powerful today, when the whole of the Russian state deploys masculine discourse in its ideology and celebrates the violation of Ukrainian as an inferior, feminine other. Anna Li’s photographs reveal a masculine gaze conditioned and normalized by traditionalist notions of sexuality. As an artist and a viewer herself, she finds and reveals the subjective positions that exist within the field of male gaze.

The key interest in many of Anna’s works is the social norm and the mechanisms that underlie it. As an individual and an artist, she deconstructs what she deems traditionalist, taken-for-granted, and thus invisible, norms. She shows viewers that norms are intrinsically tied to the stigmatization of those who fall outside the norm, and reveals a chain of social and communicative relationships that signify the norm and stigmatization. Primary among Anna’s photographic objects is her own body, which she subjects to conventional notions of beauty and ugliness to powerful effect.

Exhibition Review, Accomplices Exhibition of works of contemporary art Held in Sreda gallery, Cube.Moscow space, Moscow, Russia, 26 November to 16 January