Audible Garden: Of Memory, Oxymorons, and Hyperreality (London, 2023)

In the ever-evolving landscape of East Asian contemporary art, with its dynamic interplay of new technology, unique philosophy, and traditional aesthetics, South Korean artist Jinjoon Lee emerges as a distinctive trailblazer. Lee’s extensive body of work transcends the boundaries of artistic perception and offers a captivating exploration of human memory, poetic oxymorons, visual paradoxes, and the hyperreal condition. In his recent site-specific multimedia exhibition Audible Garden (2023) he is creating a world where these elements intertwine in a complex multimedia expression that redefines the notion of artistic medium. This essay embarks on a journey through the enigmatic realm of Jinjoon Lee’s artistic explorations, where the notion of human memory serves as the guiding thread. It is a voyage into the profound depths and ephemeral experience of human memory — an exploration that scrutinizes the power of artistic paradox and navigates the fluid boundaries of reality itself. Lee’s work ignites a profound inquiry into the very essence of that human experience, where seemingly opposite notions seamlessly collide, leaving a transformative mark on the landscape of contemporary art. The journey through Audible Garden begins with pondering the notion of human memory.

Transformation and temporality are some of the most defiant features of human memory. Seemingly uncatchable, these concepts have been challenged by visual artists for decades in arduous attempts to capture and conceptually represent these notions in artworks. While it has not been a huge problem for literati or music composers, for artists working with material objects such a task has certainly been troublesome — mysteriously almost, much like traveling through the Bermuda Triangle. The very essence of musical or literary mediums is intangible, and such mediums are naturally more suitable to represent likewise immaterial abstract phenomena. Visual artists, on the other hand, have to invent their own effective systems of signs to convey those notions. Especially in the age of abundance of such systems today, it is fairly hard for artists to develop a new suitable language to express their ideas. This crisis of representation has been deterring many artists from further exploration of human memory and its unique features. However, Jinjoon Lee stands as a distinctive exception.

The contemporary post-medium condition has marked the broadening of artists’ expressive vocabulary, which, among else, includes the use of advanced technology, site-specificity, and engagement of visitors. Temporality and transformation of memory are being excellently explored in the Audible Garden exhibition. Paradoxically as it seems, it is exactly by resorting to site-specificity that Lee was able to capture the very unspecific fluidity of fleeing memory, thus conquering notions of temporality and transformation, and incorporating them into his palette.

Just like any human memory, a site-specific project can only be associated with one particular place and a certain time in one’s life. This way the very format of a site-specific installation itself is utilized as a fundamental metaphor, upon which further discoveries of memory exploration are presented. That metaphor is best felt in the peculiar interplay of Audible Garden and Hanging Garden pieces.

The Audible Garden piece embodies the transformation of auditory information, gathered from processed data of Daejeon, Summer of 2023, into a visual image. It is the first and the largest visual representation that visitors encounter upon entering the exhibition space — vibrant pulsating black lines formed of «beads» of what appears to be sound. Those formidable painted patterns are derived by processing incoming MIDI signals that, in turn, have previously been synthesized by technological interpretation of patterns on painted spinning plaster plates. The ingenuity of semiotic deconstruction is, once again, felt vividly in Lee’s grandiose painterly presentation of the process on the main central wall.

Now the first auditory information that visitors experience in the space is the sound of the Hanging Garden installation. Here Lee creates a soundscape sculpture to portray the fluidity of memory and its relation to the collective experience. Many directional speakers of different sizes are suspended on several interconnected and freely hanging constructions, comprising a mobile. The sounds belched out from each of those speakers are flying all over the room in unexpected directions, reinforcing and canceling each other simultaneously. The unpredictability of soundscape is further enhanced by allowing visitors themselves to interact with the mobile and become a part of a collective experience. While in Hanging Garden we can clearly distinguish the sounds of sirens, birds, children, or flowing water, it soon becomes evident that it is simply impossible to isolate sounds and process them separately — the soundscape that Lee has created is such a tightly bound intricate structure, that if one were to ever take anything out, the experience will be irreversibly destroyed.

Audible Garden and Hanging Garden are very precisely situated in close proximity to one another, and those are the first audial and visual stimulators to greet visitors. The interconnectedness of those pieces in a single space firmly establishes the aforementioned fundamental metaphor of site-specificity from the very entrance. And thus Lee prepares the public for further explorations of the enigmatic realm of memory.

Building upon the fundamental metaphor of site-specificity, Lee poses time and space as irrational dimensions, around which spectators can be freely teleported. Daejeon, Summer of 2023 is certainly an apogee of multi-sensory post-medial exploration of human memory in this exhibition. Lyricism is de facto more prevalent in any artwork that concerns human memory, yet in Daejeon, Summer of 2023 artist’s own experiences are closely bound with the outer world — with the realm of technology, visual and audial representations, and the interaction with visitors. This artwork employs advanced algorithms to process visual data from plaster LPs, in which the artist has captured his daily experiences and memories, turning them into MIDI and subsequently into a complex sonic environment.

Here space is deprived of its authority and time is no longer measured as Daejeon, Summer of 2023 unfolds into a hallucinatory daydream retrospective into nowhere. In this dense multi-sensory environment there are no points of reference, nothing to cling to, everything is fluid and slips away from the grip of one’s usual perception. There is nothing to arrive to — only the artist himself has a relatively firm ground, choosing to build upon his own memories, while visitors are left in complete limbo. There is, however, a familiar feeling of remembering itself, rooted in the very act of attempting to remember something. Inducing this feeling, and letting the public experience the ephemeral, is an important part of exploring human memory and its enigmatic realm. This is the bridge that links a seemingly inward lyricism of Daejeon, Summer of 2023 to the collective experience of outward emotional response.

For the artist, extending an invitation inside, into the lyric world of personal memories, requires full acceptance of the outer world and utmost trust in visitors and their participation. In turn, they are expected to let go of previous conceptions, be not afraid of the death of space and time, and submit themselves fully to the multi-sensory experience. It is the only way to proceed through Audible Garden.

Now, what is so paradoxical in Jinjoon Lee’s methodology after all? The very approach to crafting the Audible Garden exhibition is rooted not in the traditions of static visual representation or measured performance, but rather in the rich poetics of East Asian traditional aesthetics. As mentioned before, literati have never experienced huge struggles with exploring human memory. Lee thus concentrates not on the lasting and the tangible but on the fleeting, the impermanent, the elusive. It is this intrinsically Eastern philosophical vision that allows the artist to depart from default dualism and merge seemingly immiscible notions into truly poetic paradoxical oxymorons: tangible and impermanent, familiar and foreign, organic and constructed, real and virtual. Such oxymorons are finely articulated in each work of Audible Garden, but more so in Fresh Nature: Black Milk.

One’s usual conceptions of the natural are challenged in the symbolism of Fresh Nature: Black Milk and the increasing tension between several opposing elements of the work. Lee secludes the image of a commercial plastic milk bottle and dissects its paradoxical nature — the interconnectedness of a man-made object and a purely natural element. Fresh Nature: Black Milk resorts to the feng shui philosophy and pushes it further, enriching it with new meanings that are more representative of the inherently paradoxical reality of contemporary urban dwellers. The man-made and the natural fuse into one potent sign with a rather unsettling semiotic message — our dependency on the man-made is hard-wired into us from the very birth. It is ingested with mother’s milk and is in our bones. «Black milk» is a literal oxymoron in itself, but it is no coincidence that seemingly opposing elements of this oxymoron are fluid and interchangeable. Cheap store-bought milk is rarely natural nowadays and possesses as much man-made as a plastic bottle does, and the plastic bottle in turn appears more and more in the realm of the natural — oceans, landfills, public gardens, and even our food. Distinctions between the man-made and the natural are no longer valid. They are just signs, and in reality, the man-made has infiltrated the natural to such an extent that we cannot portray the natural without man-made anymore. All of a sudden, by looking at the Fresh Nature: Black Milk, it becomes evident that the oxymoron has resolved itself in a vivid hyperreality.

Therefore, of particular interest is the oxymoronic relation between the real and the virtual, as evident in the peculiar out-of-body experience of the entire exhibition. Audible Garden as a whole indeed achieves an erasure of certain perceptual boundaries. This is done not just by departing from medium specificity and extensively utilizing new technology, but also by masterfully incorporating the tension between the real and the virtual in the exhibition’s poetic language itself. This very approach creates the condition of hyperreality. However, Audible Garden does not merely adhere to the Baudrillardian sense of it, but rather crafts its own narrative within that hyperreality, effectively making it a potent medium by itself.

While in our usual life windows tend to reconnect us with the objective reality of the outer world, the Mumbling Window turns those conceptions inside out. In this site-specific installation, Lee applies a transparent green film over supposedly the most real and objective feature of the exhibition — the view from the Korean Cultural Centre’s window to Northumberland Avenue in London. While engulfed in pungent green shades, the space is also filled with provoking sounds that are none other than complexly processed visual data, more precisely — the movement of passers-by on the street outside. The synthesized sound is also projected outside the gallery into the walkway. Such a seamless extension of the installation’s boundaries to the outside world is the exhibition’s most vivid commentary on the hyperreal condition of today, and it also explores an oftentimes surreal relationship between the outer world and its inner subjective representation within human memory.

Much like he has applied the green filter over the Korean Cultural Centre’s window, Lee applies layers of metaphors atop the hyperreal condition of modern existence. But the one metaphor that truly ties Mumbling Window with Lee’s own experience is that of traditional culture. The very genesis of Mumbling Window was conceived with an approach akin to cultivating a traditional Korean garden. The philosophy of it is to cultivate the garden in accordance with the given conditions of the space, focusing not on constructing, but rather discovering. Borrowing from traditional Korean philosophy paved the way for Lee to connect his memories to contemporaneity and build an engaging lyrical narrative.

Undoubtedly, the intricate use of advanced technology has an immense influence on crafting such a narrative. It is really the technological advancement that is largely responsible for such a surreal bodily experience of the Audible Garden exhibition. Lee successfully employs engines to derive algorithms of sonic, semiotic, and poetic deconstruction. Traditions and philosophies of East Asian culture themselves are being deconstructed and reassembled into a new language, more fit to represent the experiences of a modern human, who is perpetually balancing in-between the artificial and the natural. Perhaps, it is even the language that finally has the glossary to unite the artificial and the natural and propose them as one. This methodology goes far beyond just expressing the lyricism of the artist’s personal experience — this becomes the transformation of the inherited cultural memory as a whole.

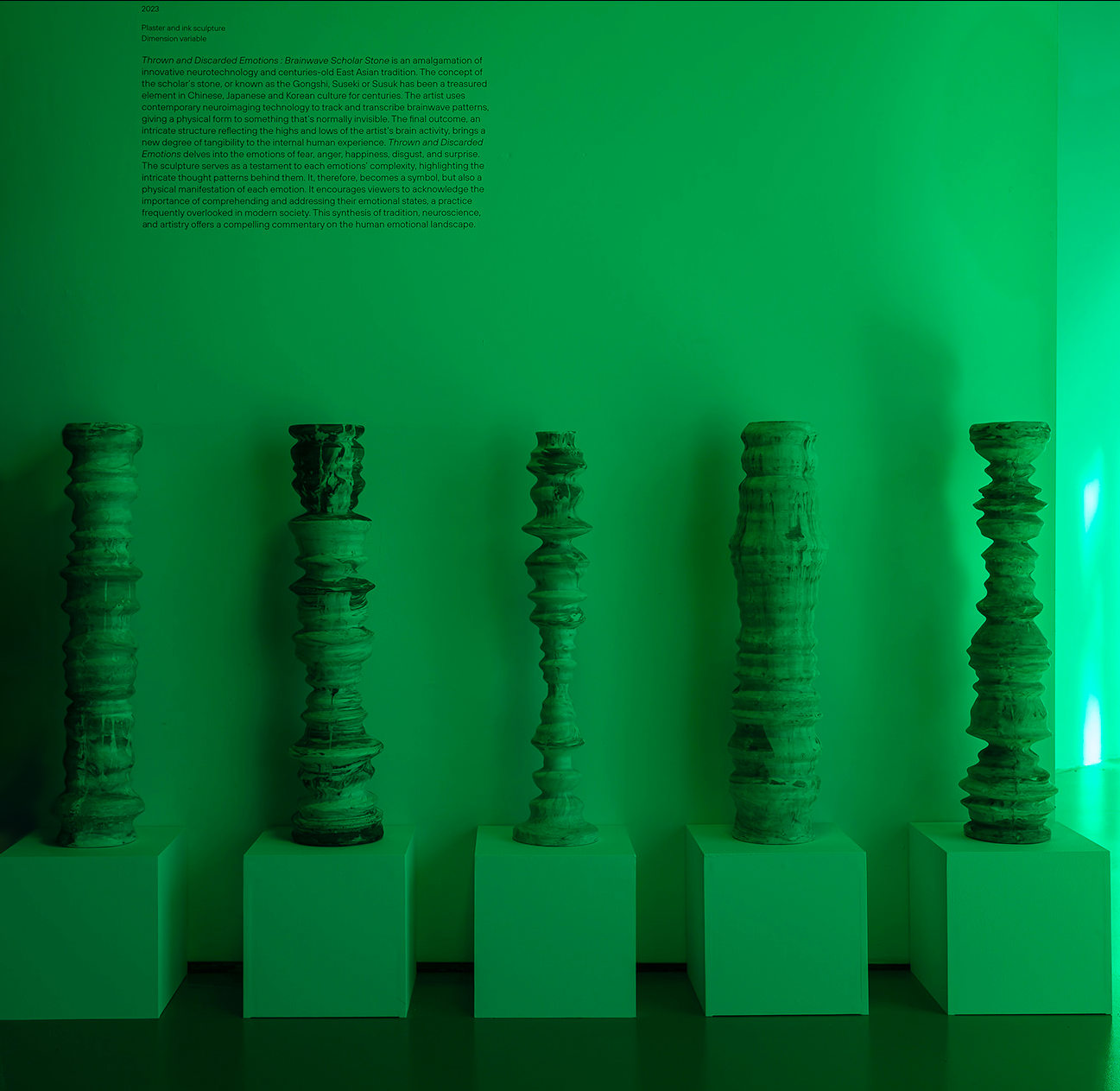

Such transformation is well exemplified in the fluid system of meanings of Thrown and Discarded Emotions: Brainwave Scholar Stone. The piece essentially consists of five plaster sculptures each vaguely resembling a suseok — a Korean scholar’s stone. Suseoks were highly appreciated objects in traditional East Asian aesthetics (called gongshi in China and suiseki in Japan) and often induced states of philosophical contemplation when viewed. The artist uses neuroimaging technology to track and transcribe brainwave patterns originating from five different emotions: fear, anger, happiness, disgust, and surprise. Then he gives a physical form to something that’s normally invisible. The outcome, an intricate structure reflecting the highs and lows of the artist’s brain activity, brings a new degree of tangibility to the internal human experience.

Therefore, the cycle through which meanings flow can be identified as follows: from archaic traditional aesthetics, through derivation and analysis of technological data, to personal artistic interpretation. The very object, the suseok, is now not just an interesting form assumed by natural rock but is a man-made tangible materialization of the artist’s emotions, stemming from his deep memory. By representing brainwave data in the form of suseok, Lee invites viewers to contemplate the very notion of aforementioned emotions and what constitutes them, therefore finishing the cycle and restarting it again. While such a concept itself is undoubtedly an abused cliché, its ingenious execution has offered a unique way to deconstruct emotions and look inside them from a completely new perspective. The novel poetical visual language developed by Lee has finally found a way to merge the artificial and the natural, the archaic and the contemporary into a singular sign with multi-dimensional meaning that flawlessly adheres to contemporary paradoxical reality.

In the realm of Jinjoon Lee’s art, memory intertwines with the power of oxymoronic poetical language, traditional culture, and post-medial approach to make sense of the hyperreal condition. This condition, made by Lee through technological deconstruction and poetic oxymorons into a sort of a medium itself, is evident in the feeling of a seamless flow of undetectable time, in the uncertainty of the exhibition’s territorial boundaries, and in where viewers’ own associations are taking them. As visitors immerse themselves in Lee’s world, they gradually forget that they are visiting an exhibition. However, it is more than that — it is an expedition into an alternate realm with its own autonomous system of signs and meanings, where memories are reborn, reconstructed, and lived through anew. Paradoxically, stepping back into actual life in turn feels strangely akin to entering a meticulously curated hyperreal exhibition.

Jinjoon Lee’s work, through its ingenious fusion of advanced technology, personal emotion, and East Asian aesthetics, offers a profound exploration of human memory. The peculiar interconnectedness of poetic oxymorons and hyperreality outlined by Lee challenges viewers to reconsider the complex nature of their own memories and the surrounding paradoxical reality. It is a testament to the artist’s remarkable ability to capture a fragile interplay of opposites, much like in the feng shui philosophy, offering an unparalleled insight into the intricacies of human memory. In this captivating journey, Jinjoon Lee invites us to question the boundaries of our existence and the profound role that memory plays in shaping our perception of reality.