The ontological revolution of slime

The snake gourd blossoms.

My throat blocked with phlegm,

I am already a Buddha.

Masaoka Shiki

Interpreting the three principles of Aristotle’s metaphysics known as matter, form and privation, Plutarch sets up a mythological correspondence. In Isis and Osiris, we find steresis (privation) represented by Seth or Typhon, a malicious god of mortality and disharmony:

Empedocles calls the beneficent principle “friendship” or “friendliness,” and oftentimes he calls Concord “sedate of countenance”; the worse principle he calls “accursed quarreling” and “blood-stained strife.” […] For these, however, Anaxagoras postulates Mind and Infinitude, Aristotle Form and Privation […] So in the soul Intelligence and reason, the Ruler and Lord of all that is good, is Osiris, and in earth and wind and water and the heavens and stars that which is ordered, established, and healthy, as evidenced by season, temperatures, and cycles of revolution, is the efflux of Osiris and his reflected image. But Typhon is that part of the soul which is impressionable, impulsive, irrational and truculent, and of the bodily part the destructible, diseased and disorderly as evidenced by abnormal seasons and temperatures, and by obscurations of the sun and disappearances of the moon, outbursts, as it were, and unruly actions on the part of Typhon. And the name “Seth,” by which they call Typhon, denotes this; it means “the overmastering” and “overpowering,” and it means in very many instances “turning back,” and again “overpassing.”1

In Plutarch’s treaty, philosophy is wedded to mythology: Osiris is form, Isis is matter, and Seth is privation. The same logic is followed by Maimonides who states that the mortality of Adam, or form, is caused by the Serpent, or privation.2 Here we should consider the fact that during the period of Old Kingdom Seth was not regarded by Egyptians exceptionally as negative; on the contrary, he was protector of the king.

Aristotle’s hylomorphism was also influential in the development of Christian thought; not matter itself was demonized but only its exposure to destruction and instability. In order to obtain salvation and immortality, the sinful flesh should become like the Body of Christ, it should get rid of its sin which is privation. Tertullian calls Jesus “the Lord of the flesh”.3

For even speech comes from an instrument of flesh, accomplishments need the vehicle of flesh, as do pursuits, talents, and works, businesses, functions; the whole life of the soul is bound up with the flesh to such a degree that cessation of life for the soul means nothing else but a departure from the flesh. So even death itself belongs to the flesh, as does life also. Further, if all things are in subjection to the soul through the flesh, they are in subjection to the flesh also. When you make use of a thing, you must at the same time make use of the instrument which enables you to use it. So the flesh, while it is considered attendant and handmaid to the soul, is found to be also its partner and joint heir. And if of temporal things, why not also of overlasting?4

Far from ignoring matter, Christians make it a central point of their program. Thus, if the soul is saved, it does not mean that material existence stops, but that matter is transformed and its corruption is banned. Christianity is a religion of eternal body free from illness, ageing and death. After the Last Judgment, the world of destruction should be eventually taken apart from the one which is wholesome: the flesh will become incorruptible, while all dust will be gathered in the hell. And if we apply the terms of Aristotle’s ontology, we could say that the Christ redeems Eve (matter), puts an end to privation (steresis, sin) and thus saves Adam (form, soul). This became a solid foundation for a fear of sovereign, ungovernable matter deprived of any form which is always in motion and subject to changes and floating affects–matter which has given preference not to logos, but to chaos, not to immortality, but to death.

In An Investigation of Horror, Leonid Lipavsky, the main theoretic of OBERIU, does not dwell upon the ontological premises of this emotion; basically, he approached it as a phenomenologist, thus, giving us a chance to reveal its genealogy. From his work, we find out that the greatest fear of the Christian race raised by Aristotle is to lose their identity and form, including a fear of open space where one can get astray, like in the sky, grassland, or ocean, as well as of blood when it springs out, and its stream ramifies outside the body, becoming “a red plant in the green landscape, and suddenly, we realize a vegetal nature of our internal organs”.5 Lipavsky points out that horror is not at all based on a sense of danger, but that it is totally autonomous. Moreover, he affirms that the horribleness of a thing is its objective quality, like color or outline.6 At this point, there is but one step to Aristotle’s ontology. In fact, Lipavsky gives different examples of formlessness–which he regards as a quality of things–and identifies it with a sense of horror.

Among the first thinkers who raised the problem of the formless was Saint Augustine, Bishop of Hippo. As he puts it, “things formed are certainly superior to things unformed”.7 Commenting on Genesis, he asserts that formless matter was created before all rest, but this priority is not “by eternity”, for “nothing can be related of this unformed matter unless it is regarded as if it were the first in the time series though the last in value”.8 This formless matter had appeared before time was created, “because the form of things gives rise to time”.9 Let us assume that time in this prior chaos was also a sort of mixture; it was not yet separated from the thick of primal substance, or in a word, it was presentpastfuture together. Further, Augustine suggests a strange and interesting idea that before God said, “Let there be light,” there had been some subtle creatures which languished in formlessness.

Now what you saidst in the beginning of the creation –“Let there be light: and there was light”–I interpret, not unfitly, as referring to the spiritual creation, because it already had a kind of life which you couldst illuminate. But, since it had not merited from you that it should be a life capable of enlightenment, so neither, when it already began to exist, did it merit from you that it should be enlightened. For neither could its formlessness please you until it became light–and it became light …10

Augustine calls the unformed condition “the deep darkness of the abyss”11 ; he spends some time meditating upon the formless—what is the primary state which was in the beginning of the creation and which God enlightened or shaped. First some unusual, wild and horrible images came to his mind, but soon he realized that they all still should be considered as something differentiated. He plunged deep into thought and got a sense of what the principle of mutability is:

For the mutability of mutable things carries with it the possibility of all those forms into which mutable things can be changed. But this mutabilityk–what is it? Is it soul? Is it body? Is it the external appearance of soul or body? Could it be said, “Nothing was something,” and “That which is, is not”? If this were possible, I would say that this was it, and in some such manner it must have been in […] Whence and how was this, unless it came from you, from whom all things are, in so far as they are? But the farther something is from you, the more unlike you it is–and this is not a matter of distance or place. Thus it was that you, O Lord, who art not one thing in one place and another thing in another place but the Selfsame, and the Selfsame, and the Selfsame…12

So, from Augustine’s point of view, the absolute formlessness is mutability itself, the dark abyss where the principle of impermanence dwells, while God is constant, stable light.

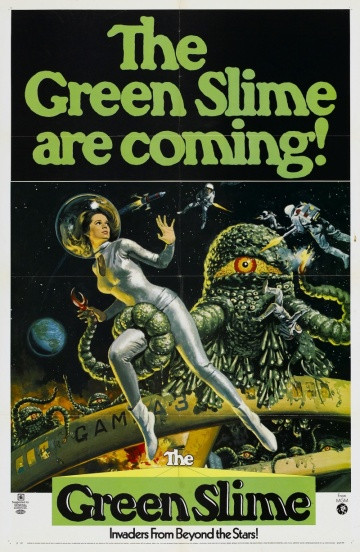

What exactly are the things which cause a fear of homogeneity, according to Lipavsky? These are mud, grease, mire, saliva, slime, bowels, lungs, heart, all other internal organs, secretion, meat, seminal fluid which is a matter of particular interest to the philosopher, because, by studying it, we can reveal what homogeneity is. The protozoa and marine species are terrible, because “they are almost liquid”.13 By the same logic, there are certain sounds connected with overflowing, inarticulate life and indicating its consistence, like squelching, eating, and sucking sounds.14 All outspreading and bubbling is also horrible: a spider, a louse, and an octopus; a toad, a caterpillar, and a crab; an ass, a breast, and an abscess–and, of course, a scolopendra. It is all about bubbles, or outgrowth, or bubbles with outgrowth. The amorphous substance is horrible as it is–for instance, if a child is afraid of jelly, that is because it is a resurgent matter which is alive, but formless, therefore deprived of logos. It is alive, but indefinite. Lipavsky calls that “illegal animacy”.15 The inarticulate life is something really horrifying. A bubble is most horrible and erotic, for we find the principle of selflessness well-expressed here.16 Lipavsky speaks about a dead man who is scary, because he has some different way of living which can be seen by growing nails and hair; his life is a process of putrefaction.17 And now we are close to comprehending what horror is. Lipavsky anticipated the intentions of European culture for half a century ahead. At last, life from the dead has become a central concern. We watch horror films, because horror is attractive. When, in the Vth century, The Revelation of St John the Devine was recognized as canonical, a story about risen from the dead took its place among the cultural archetypes of the Christian world.

It appears that Ben Woodard is not familiar with the heritage of Leonid Lipavsky. At least, in Slime Dynamics: Generation, Mutation, and the Creep of Life there are no references to any of his works. So let us think that the writings of two philosophers are congenial, because they both seem to be inclined to blennophobia. Of course, the coincidence is striking: both speak about bubbles, dead bodies, jelly, slime and so on. Both insist that horror is directly connected to a sense of danger, but most probably results from extreme disgust:

Horror comes from abhorrence. And this cannot be caused by anything which has practical significance; it is esthetic.18

Woodard introduces the notion of “dark vitalism”, he writes about “the sickening realization of an inhospitable universe” and “fungoid horror and the creep of life” .19 Scared by destruction, wear and ageing, he refers to a work by Iain Grant titled as Being and Slime to confirm that “our existence is then only a stacking of putrescence, an infusorial mass or protoplasm or an originative but rotten unity”.20 In support of his own vitalistic pessimism, Woodard presents three arguments which can be characterized as Cartesian, Christian and Aristotelian. In the first place, our mind is too weak to discover the mysteries of nature. Secondly, vitalism gets out “bad news”, for it predicts that in the end everything will ruin (eschatology). The third argument is that the hidden basis of life, which is bubbling and flowing, fraught with bacteria and fungi, and stems from seminal fluid already denoted as nightmarish by Lipavsky, is esthetically unacceptable. Lipavsky and Woodard share the same fear of “the impersonal spontaneous life”; they both are gripped with terror about “a half-liquid non-organic mass in which we can observe a process of fermentation going on and see the areas of tension and power knots appearing and disappearing. It is stirred by bubbles which can accommodate changing their form and flattening”.21

In comparison to Lipavsky, Woodard is more neurotic, because nowadays we have sophisticated computer games, horrifying cinematography and strange literature to develop an acute sensibility to unstable substances. All that is reflected in Ben Woodard’s blennophobic book infused with anxiety. The author is sympathetic to speculative realists without recognizing the fact that he himself stands for privileged access to the world: the feelings he describes are specifically human and have their roots in the Christian and Aristotelian ontology. It is quite probable that Woodard proceeds from Sartre’s ideas, although he does not mention any of them directly. We would like to point to the following excerpt from Sartre’s treaty Being and nothingness where he states in line with Gaston Bachelard’s psychoanalytic materialism that the qualities of things have some psychic identity which are not dependent on our projections:

On the other hand, sliminess proper, considered in its isolated state, will appear to us harmful in practice (because slimy substance stick to the hands, and clothes, and because they stain), but sliminess then is not repugnant. In fact the disgust which it inspires can be explained only by the combination of this physical quality with certain moral qualities. There would have to be a kind of apprenticeship for learning the symbolic value of “slimy”. But observation teaches us that even very young children show evidence of repulsion in the presence of something slimy, as if it were already combined with the psychic. We know also that from the time they know how to talk, they understand the value of the words “soft,” “low,” etc., when applied to the description of feelings. All this comes to pass as if we come to life in a universe where feelings and acts are all charged with something material, have a substantial stuff, are really soft, dull, slimy, low, elevated, etc. and in which material substances have originally a psychic meaning which renders them repugnant, horrifying, alluring, etc. No explanation by projection or by analogy is acceptable here.22

Sartre offers a rather doubtful evidence when he begins to speculate about children. We have no possibility to go into infant psychology now, but it would make sense to emphasize that, quite to the opposite, very often children show no sense of disgust and express no fear while playing with different filthy substances. Both Woodard and Lipavsky are assured that horror we experience is not tied with potential danger, and so it is substantive. In the same way, Sartre disjoints the unpleasant impression caused by slimy things and the damage it could involve. The Sartre’s ontological psychologism brings us back to old metaphysical problems. The categories “being” and “nothingness” belong to the Judeo-Christian and Aristotelian metaphysics. It is in the Old Testament that we find the notion of nothingness which corresponds to zero. This is an inversion of being which existentialism usually works with, while, in the Christian (Augustinian) interpretation, nothingness is equal to amorphous substance which has no order in itself. When Sartre objectifies the negative qualities of sliminess, it just shows that he is contaminated with St Augustine’s ontology, because in his works, the pure nothingness of existentialists is confused with nothingness as formlessness. In “Nausea” he painted a vivid picture of the ontological revolution which is now going on within old hylomorphism, imagined by Roquentin.

As soon as matter submits to form, it secures individuation and differentiation which do not let human bodies blossom, but the same dark vitalism (or vegetative fluidity which Lipavsky has already told us about) skulks under the pressure of form: blood is just a red plant among the green ones. We come across the ideas which are unexpectedly similar to those enounced in Being and Nothingness:

This liquidity can be compared to the juice of fruits and the human blood–which is to man something like his own secret and vital liquidity–this liquidity refers us to a certain permanent possibility which the “granular compact” (designating a certain quality of the being of the pure in-itself) possesses of changing itself into homogenous, undifferentiated fluidity…23

It is symptomatic that Ben Woodard called his philosophic blog “Speculative Heresy”, as, in the final reckoning, all his fears are based upon a purely dogmatic platform. Insofar as he claims a man to be a victim of the omnipresent slime, the dark vitalism of the Universe, he makes us feel the awful tragedy of human existence, our insecurity in face of fungous, creeping, bacterial powers. That is precisely what accuses him of anthropocentrism, let it be pessimistic. Woodard deliberates matter from any dictatorship of form and invests it with autocracy, but he is not at all glad to acknowledge this–as contrasted with, for instance, Deleuze who opens up new creative potentialities in upturned ontology. In his work A Thousand Plateaus, he aptly showcased the principle of inverted hylomorphism: an artisan surrenders to the will of wood when he goes to find a certain kind of fibers. This is an example most commonly cited from Aristotelian physics (an artisan and a matter, formal essence and substrate), but now it is turned upside down, so that an artisan gets a passive role, and we can witness a Phillidian philosophic theme. A submitting, repressive form–an artisan, a demiurge, an author–is not needed any longer; the focus is on the surface of things:

…what one addresses is less a matter submitted to laws than a materiality possessing a nomos. One addresses less a form capable of imposing properties upon a matter than material traits of expression constituting affects.24

The aforementioned term “Phillidian” refers to an ancient legend about a hetaera known as Phillida (Pancaste, Phyllis) who was so charming that Aristotle gave her a ride on his back and let her urge him with a small whip in order to win her affection. This story and multiple illustrations which usually accompany it 25 , reverse the principle formulated by Stagirite in Metaphysics:

Yet the form cannot desire itself, for it is not defective; nor can the contrary desire it, for contraries are mutually destructive. The truth is that what desires the form is matter, as the female desires the male and the ugly the beautiful…26

Slime is materiality which does not need any form; moreover, the harmful, bacterial slime which Woodard writes about, contributes to destruction of forms. The revolutionary message of Woodard consists in the inversion of ontological principles: matter betrays form with privation and becomes ungovernable, chaotic, and dangerous.

In his Treatise on Tailor’s Dummies, Bruno Schulz gives a brilliant formula of Phillidian ontology: Father delivers a discourse upon the self-sufficiency of matter and the Demiurge’s unjust monopoly of creation. And although his creative method is incomprehensible and cannot be imitated, there are some illegal actions, the dark Demiurgy which gets its source from matter itself: these are subtle effects, vibrating surfaces, dull shivers, coagulated tensions, indistinct smiles, twinkles, dreams, soft shapes .27 The shifting structures of matter are liable to destruction, spontaneous metamorphoses, and the dark Demiurgy which Father speaks about, utilizes its qualities. There is nothing durable or solid in this second creation, all is unfinished, contingent and valid for one occasion; gestures are disconnected and organs do not form a single unit. There is a bias towards papier-mache, coloured tissue, oakum and sawdust. We can clearly see a fluffy, porous nature of hyle in all what is short-term and dissoluble, but the Demiurge is eager to conceal it in the harmony of the world. The rhythmic and concordant play of life does not allow a complete manifestation of the substrate’s peculiarities; what is needed for that is creaking, clumsiness, ponderosity, bearlike awkwardness, and a heavy effort .28 Hence the main constituent of the Schulz’s prose is gurgling metaphorics, a synaesthetic cloaca of sensitivity in which vision, hearing, smell, touch and taste are mixed up and whipped into a batter clod of the primordial sensor not divided into separate perceptions. Schulz endeavored to generate a teeming text. Interestingly enough, Phillidian motives in Schulz’s works are free from pessimism or anxiety; he is able to fully enjoy his dark Demiurgy which is accordant with his poetic style. There is no such excitement shown by the author in Slime Dynamics; we would rather say that, in a sense, he pursues a line of Diderot’s “enchanted materialism”29, as if he has fallen under the same spell. However this may be, as a speculative realist, Ben Woodard tends to feel horrified and pessimistic about his own revelations, which forces us to admit that his approach is basically anthropocentric.

Anton Zankovsky

1. Plutarch (1936), Moralia (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), v. V, pp. 119–123.

2. The Russian translator and commenter of The Guide Mikhail Schneider notes that Maimonides sees woman as a symbol of matter and privation as a source of universal evil, Satan, Angel of death, wrong motivation (see: Ben Maimon, Moche (2010), Putevoditel rasterjannih (Jerusalem and Moscow: Mahanaim–Gesharim, p. 108).

3. Tertullian (1922), Concerning the Resurrection of the Flesh (New York: The Macmillan Company), p. 3.

4. Ibid., pp. 19–20.

5. Lipavsky, Leonid (1993), “Issledovaniie uzhasa” [An Investigation of Horror] in Logos, vol. 3, № 4, p. 79.

6. Ibid., pp. 80–81.

7. Augustine (1955), Confessions, trans. Albert C. Outler (Philadelphia: Westminster Press), p. 364.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Augustine (1955), Confessions, trans. Albert C. Outler (Philadelphia: Westminster Press), p. 371.

11. Ibid., p. 374.

12. Ibid., p. 335–337.

13. Lipavky, Ibid., p. 82.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid., p. 81.

16. Ibid., pp. 82–83.

17. Ibid., p. 83.

18. Ibid., p. 85.

19. Woodard, Ben (2012), Slime Dynamics: Generation, Mutation, and the Creep of Life (Winchester and Washington: Zero Books), URL: https://ru.scribd.com/read/240214362/Slime-Dynamics#.

20. Ibid.

21. Lipavsky, Ibid., p. 85.

22. Sartre, Jean-Paul (1956), Being and Nothingness. An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: Philosophical Library), p. 671.

23. Sartre, Being and Nothingness, p. 601.

24.Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix (1987), A Thousand Plateus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press), p. 430.

25. See: Voskobojnikov, Oleg (2014), Tisjacheletneje tzarstvo (300–1300). Ocherk christianskoj kulturi Zapada [The Thousand-year Kingdom. Review of the Western Christian Culture. 300-1300] (Moscow: Novoje Literaturnoje Obozrenije), p. 372.

26. Aristotle, Physics, URL: http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/physics.1.i.html.

27. The Fictions of Bruno Schulz: The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium under the Sign of Hourglass, 1988, trans. Celina Wieniewska (London: Picador), pp. 39–41.

28. Ibid.

29. See: De Fontenay, Elisabeth (1984), Diderot ou le materialisme enchanté (Paris: Grasset).

На английский перевела Софья Спиридонова