a GLOSSARY for GLOBAL MOVEMENT

by Anastasia Kolas (incl. images)

From Nacre Journal Issue 3—Hyggelig—Winter 2020 (Archive)

If showing up, is what counts, the permits needed for artists to take part in the discourse are not directly addressed in the art sphere: neither the questions of immigrant or migrant experience — the question of working visas, the nitty-gritty, the stamps, iridescent visa logotypes, watermarked and embossed, keys to the discourse; nor the trauma of migration facing the confidence that comes with embeddedness and belonging. The subjects are talked about through stats, or analyzed and speculated upon in exhibitions, but rarely are they considered structurally by educational institutions, residencies, or by curators.

Meanwhile, the polemical borrowing of immigrant identity to validate one’s attention-seeking or programming choices has been highlighted by the 2019 contention of 4column’s article vs Tramps' open letter. This, illuminating even if extreme, reaction of both parties involved, highlights a deep-seated inability, to the point of utter disinterest, to transcend one’s own experience to enter into another. The flare up is a symptom of a larger underlying tendency that is structurally incited and residually dispersed throughout the art sphere. Was this debate an issue of who is who (immigrant or appropriating insider)? Or was this all about the figure of Kai Althoff, a not-at-all underrepresented artist, and the question of his work shown at supposed indie gallery in Chinatown, after having just had (an excellent) solo show at MOMA? From where I stand, the debate looks to be about US/NYC art scene and the strategic maneuvering its climate requires, as opposed to anyone’s interest in identity per se, on either side of the, essentially, non-conflict.

Migrant is a term one sees often used by the media as an all-terrain vehicle. Literally, it means someone who’d moved. Most commonly, colloquially or in the news, it is mis-used in place of saying: a refugee. The opacity is meant to superimpose an agency that doesn’t exist onto a person fleeing from hardship.

Through assembling a glossary of global movement, what I am trying to do is to show how difficult it is to consider thoroughly the structural impact of the nuances involved. It is much easier to get submerged into rhetoric and begin juggling the mobility vocabulary as if immigration is all but a barbie clip-on dress, and can be put-on, changed or discarded depending one one’s mood.

Instead, I propose here, to practice holding all of these terms and ideas at once, and see what happens then. I am well aware, that the people who I’d like to reach with this information are least likely to read it. Nevertheless, I press on, as they say in New Zealand.

For an artist predictability of a bio can cancel the question of making their work. The push pull of having to explain, be allotted, and refusing to be assigned an all encompassing singular meaning, is a place of ongoing friction as many artists grow weary of representing countries at the Venice Biennale2, weary of identifying with a nationality, ethnicity, gender and any kind of predetermined identity. Though to some, the choice of avoiding biography is not as clear or available.

What has transpired since I immigrated to Canada, during the last 20 years spent across various locations in North America and Europe, is that the language of broad-base identity politics, often in clumsy attempts for repair, suffers from indolence. Jia Tolentino asks in her succinct review of Ivanka Trump’s book: “What can a woman born with a silver spoon in her mouth teach people who use plastic forks to eat salads at their desks?”3 What can someone who has never been faced with leaving their home country by force or circumstances, teach those who had risked everything for it? In many ways this glossary is a list of platitudes that, I am surprised to discover, need to be revisited, defined, clarified. The glossary is surely incomplete and idiosyncratic to a degree. Below, I risk to offer a personal take on the movement of the varied by access population into the honeyed center of European Union and North America.

Cesar Aira begins his autobiographical book “Birthday” by admitting to discovering a gap in his knowledge of a basic natural law: the cycles of the moon visible in the sky as a crescent or fully lit surface of the planetary satellite. Retracing the formation of his false belief that shaped the subsequent decades of his life, he places his moon ideology’s root roughly at when he was 8. He writes: “It wasn’t the case ‘I’ve never thought about it’; I thought about it, once, which is worse”.

In the UK, following Brexit vote, it was popularized to normalize the discussion on immigration in an attempt to release the word immigrant from associated with it stigma. Fashion designer Ashish Gupta can be said to be the original source of the IMMIGRANT T-shirt 4. It’s important to note the original was not made for sale but as a statement T-shirt he wore at the end of his own runway. An avalanche of requests to buy it, which he obliged, predictably followed the show.

“We are all immigrants anyway, right?” — said a poet with no hit of irony, sitting across from me in a glass box canteen. He smiled at me, bathed in the rays of majestically setting over the Rocky Mountains sun. Spoon stopped in mid-air en route to my agape mouth. The poet was sat in the canteen because he was in residency, described as: “a new frame of contemporary Canadian writing. Increasingly, today’s writer is participating in acts of acknowledgement, reclamation, restoration, and resurgence regarding minority, diasporic, and Indigenous histories.”5 We continued to discuss this statement over soup. As I tried to digest his point of view, it became even clearer that he meant it in earnest because he never considered it otherwise. It seems too obvious to point out the dissonance of his statement and the thesis of the program he was a part of. Let me ask this again: Are we, all immigrants?

GLOSSARY

Immigration: a bureaucratic term used by governing bodies and government agencies that encompasses all processes and paperwork involved in crossing a border for permanent, temporary, long or short period of time, not to be confused with being an immigrant.

Expat: birthright passport holders of Common Wealth, US, UK and EU. It has come to my attention that the term “expat” is being rejected by the people it usually describes (today, not historically). To me, expat is a word that seems to be more rooted in English than all the other words I am using to write this glossary: being an expatriate denotes a certain set of privileges and has strong roots in British Empire expansion. Migrant, here makes another appearance, as a desirable vocabulary update/replacement of expat, for those who reject the description for it uneasy association with patriotism (and all of its nationalism or xenophobic associations), adding to further confusion to the experience language is meant to articulate. Those described as expats today, are born into relative to most, stable political and economic reality and choose to relocate. Expat moves for work, or love, or simply just because they have the flexibility, means and options. This includes all Nth generations, the descendants of immigrants, born and brought up in the western context. Intra-family immigration is the distance between being born in a new country and living with parents or grandparents who are essentially, from another world. The question that affects one’s global mobility, and thus access to freedom of speech, participation and resources today, is the timeline: the distance to these experiences and the conditions that followed and are present to one at birth, and IRL in 2019. Class and race of expats, is distinct from the issue of immigrant status and it is key not to conflate all of the related terms into one. Structural racism — may affect one’s global mobility through the “random searches”, red-flagging, and other instances of slowed or aggravated travel. An expat of colour could be assumed to be an immigrant, as the language reflects the persisting racial bias. However, this glossary is written with a purpose of highlighting logistics of immigration and citizenship, and all of its benefits, or restrictions — where the language is at the intersection of legal and affective experience.

What many expats choose not to know, is that if you are from any other region but “the west”, the very process of traveling as a tourist, or application for a legitimate working or student visa, let alone ability to relocate, immediately comes with additional red tape of restrictions and scrutiny, in addition to obvious obstacles such as money, access to information and language barrier. Expats move because they can. If all fails in their new adventure of spending a year in Paris or New York, they have a home country of birth to return to, of high living standards, family, friends, social services, and importantly, understanding of how it all works, human rights, free speech and a sense of belonging. That this level of living standard rests on mining international resources and labor, and colluding with authoritarian and violent governments, is a separate story, though one to keep in mind when referring to other terms in the glossary below.

Immigrant: Immigration is not an event of one’s parents or grandparents life, but rather a lived experience in one’s own timeline. Immigration is distinct from relocation in its entirely speculative and dislocating quality. Immigrant status is given after over several years of preparation, one is able to meet all point system requirements (age, clean record, education, savings, language). Countries open to immigration are Australia, New Zealand and Canada. US has a randomized and thus, unreliable for life planning, Diversity Visa (formerly Green Card Lottery). As an immigrant through any of the above programs, one chooses to take a risk and try their luck in a whole new place, leaving behind often precarious, unsafe or oppressive conditions. More often than not, this person has sold or taken all of their worldly possessions with them. They may or may not see relatives again, and may or may not be allowed back as a visitor to their own country. They may have to give up their birthright passport. No one is waiting for them on the other end, expect perhaps another immigrant, to help you navigate a whole (conceptually) new system of bureaucracy, language, customs, employment, rental agreements, banking, gestures. This help is often offered for a fee.

Adaptation and assimilation varies and is strongly affected by age, family formation and financial reality of the family or individual at the point when they enter this new life. There is a new physical landscape: architecture, transport, temperature! Natural habitat — the view outside your window! It’s a blind date with a new life, and it turns out they may not like it. Let alone love it, or feel at home. It is simply not always possible to pick up again logistically or financially, and “go back”, as have been suggested to me by American president and some of my blazé euro-american peers. Though people do. Sometimes heart transplant fails hard and I know of those who chose and returned to an authoritarian regime for the sake of community and belonging. This bracket omits all the industrious souls who are able to enter into educational institutions and enter the work permit system on completion, without the need to immigrate, however the conditions of cultural adaptation and assimilation process, remain.

It is worth noting here that all European countries are closed to immigration (relatives only). EU accepts work-sponsored, study or spouse visa applications. Some European countries accept refugees. Germany has a simple straight forward freelance work visa application for expats or, global nomads as they sometimes, um, self-describe. The visa is open to other nationalities too, although with markedly less ease. The ease of freelance working visa along with formerly cheap rent, helped to create Berlin’s art and music scene, and in many ways, led to the eventual gentrification of the city following the model of London and New York.

Golden visa: Investment immigration accepted by most countries in the world, an oligarch favored method of re-settlement, based on what one can invest in a given country, most commonly through buying a property. This type of immigration offers, allegedly, stimulus to the economy of the country which passport one’s essentially buying.

Refugee, asylum seeking, is a form of hardship migration with yearly quotas that differ from country to country. Refugee status can be claimed based on life threatening conditions where one is forced to relocate, or had to flee under duress such as war, violence, extreme poverty, environmental disaster, political discrimination or persecution. A refugee claimant still has to meet the requirements of the system, hence waiting lists, refugee camps, etc. Those able to apply for status from inside of a country, having arrived on a tourist visa, or by illegally crossing the border, are exceptions to these conditions with a situation of their own: during the hearing of their case the refugee status applicant cannot leave the settlement camp or the country where they are claiming asylum. This may take years and they are locked-in or risk losing the application.

Dreamers — American-born descendants of illegal immigrant families. This group of American-born citizens is restricted by laws and familial ties from being able to claim birth-right citizenship, making this group forced to choose from two options: to be essentially imprisoned for life undercover in the US in hopes of getting naturalized, or leave — where to? Dreamers are 100 percent American non-citizens with patchy access to education opportunities and employment, and with the life under threat of deportation to what is essentially a foreign country of their parent’s origin.

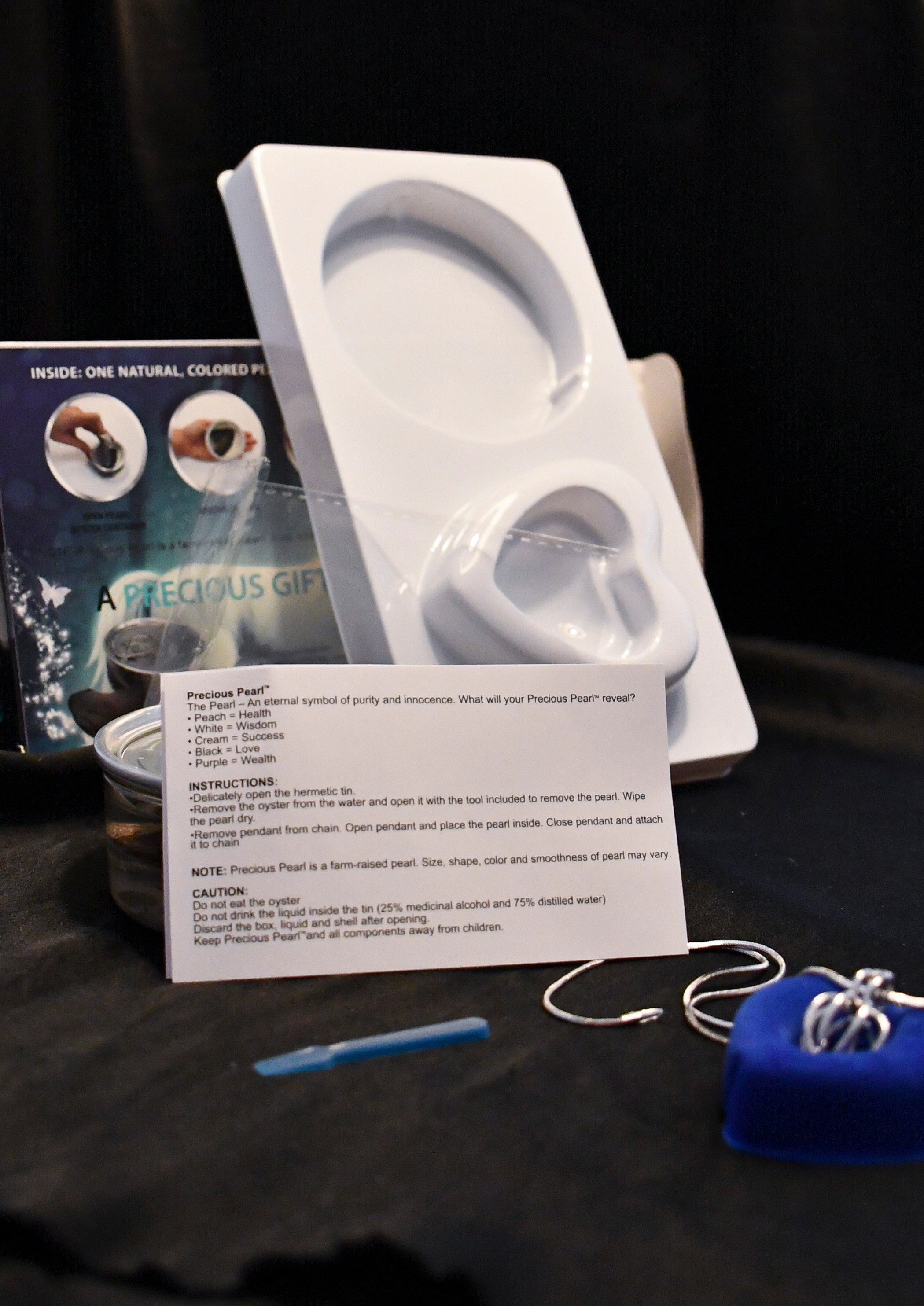

ɔᴉʇsɐld sᴉ lɹɐǝd ǝɥʇ

Immigrants, and the investment immigrants, conflated with refugee and asylum seekers, are in total frequently summed up under the blanket terminology of legal or illegal immigrants. Illegality here, is often survival tactic of someone who by a margin does not meet the requirements of immigration or asylum seekers’ quota, desperate, or convinced themselves of promise-land, a better life, and tries overstaying tourist visa or crosses the border without documents and can thus be deemed an illegal immigrant. Often these are the people, invisible, cleaning and cooking, hired under the table so the establishment owner can save on taxes, or much more rarely, to actually help them at personal risk of being charged. Those crossing the southern US or any EU border are not immigrating: most are refugees seeking safety, fleeing from regimes or situations, some of which are side-effects of that very thing we call the American Dream or European Culture.

The Polish workers the Brits are happy to employ when it’s useful and then treat xenophobically when it isn’t6, are not immigrants, they are EU member state citizens as of 2004 and are migrant workers benefiting from the same mobility as Italians, Spanish, French. The people of countries that joined the EU after 2004 do come with a bouquet of complex histories and war traumas. These countries are: Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovenia (yes Melania’s homeland), Slovakia, Croatia, Bulgaria and Romania. In relation to global mobility, EU membership offers numerous options of education in member states that is free or is charged at drastically lower than international rates. And of course, EU membership offers freedom of movement, including beyond EU borders, to the allied countries. EU membership, however, doesn’t remove the history that preceded it.

Twilight zone. The ambiguous gray zones of global mobility are many: trustafarians from authoritarian or dubious regimes do exist, as does historical diasporal aristocracy, royalty, oligarchs, their extended relatives and descendants.

What to do with an immigrant that has moved, like myself, this time by choice with the new passport from a western country to another, is there an expiration date on the original experience itself? Am I now — an expat?

The access to benefits of free global movement cannot be rationalized to describe how one advantage simply cancels out the other. However, the right passport, providing an educational path, employment market and network access by birth do alleviate, help navigate, and lessen other systemic roadblocks. Generally, my feeling is that those unaffected by the debate of immigration personally (with a few always remarkable exceptions), are somewhat able to get their heads around the straightforward and even better, illustrated, cases, but have a much harder time adjusting to long-term effects on persons they meet or more complex ideas of hybrid cultural build of many individuals who have had to immigrate.

As it stands, in some form or another, immigration, displacement, structural and emotional, is something one may be going through for the entirety of their life, but all of these stories of blur have exceptions, conditions that alleviate or worsen the issue. Frame that t-shirt and hang it above your bed if you like, wear it to a protest. There’s much that can be done besides clicking: add to cart, to fight the stigma of being an immigrant.

This glossary is certain to change over time as government politics and policies cycle through, and as environmental migration becomes, unfortunately and likely, more commonplace. The environment, after all, simply mirrors the premise of global structure in place now. A seat at the table does equate to being a challenge to the place-setting itself. As overarching valances of the existing superstructure remain unchanged, history shows time and again, all chances are we are setting ourselves up for replaying the issues in a game of musical chairs, while resources dwindle and living turns to be increasingly atomized.

_

Thank you to Heather Anne Halpert and Tatsiana Zamirouskaya for their input while writing this essay and glossary.