The Curse of Silence: About Haim Sokol’s Underground Exhibition in Tel Aviv

Haim Sokol’s underground exhibition, The Victory Museum, in Tel Aviv was an act of artistic defiance amidst the near-total silence of the Israeli art world regarding the war in Gaza. In an era where expressing regret or anger about Israel’s actions is equated with betrayal, Sokol’s private exhibition revived the tradition of Soviet underground art, creating a space where themes of war, displacement, and historical trauma can be explored.

Sokol, a Russian-born artist with an extensive career in Moscow and Israel, has long engaged with themes of alienation and disrupted identities. His recent works examine Israel’s fractured consciousness, reflecting on war’s impact on individuals and collective memory. His installations and paintings merge personal and historical narratives, interrogating the ways war distorts identity and blurs the lines between victim and aggressor.

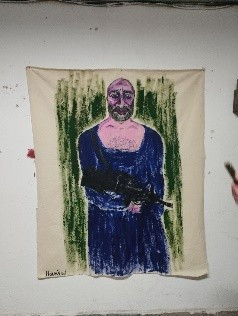

Notable works include Self-Portrait, depicting the artist in his mother’s dress with a gun, referencing Israeli soldiers’ looting in Gaza; King’s Stone Head on the Plate, evoking martyrdom and historical beheadings; and The Skeleton Building, a haunting reflection on destruction and erasure. Other installations, such as The Bag and The Bird and the Football, juxtapose fragility with war’s brutal permanence.

Sokol’s work is a rare voice in an artistic landscape silenced by fear and censorship. His exhibition asks a pressing question: if the war in Gaza cannot be acknowledged in Israel’s public art spaces, is silence the only response artists and curators can offer?

The ongoing destruction of Gaza has presented every Israeli Jewish artist with a limited set of options for creatively expressing the emotions and thoughts brooding within us. Only a courageous minority has chosen not to remain silent about the events unfolding before our eyes daily. However, all such attempts must take place outside the framework of the official establishment, and even independent galleries are reluctant to exhibit these works of art.

One of the consequences of the current war is the obliteration of the right to feel compassion for its victims. The only form of compassion that is permitted and lauded is that directed toward the Israeli victims of October 7th. Any expression of regret, shame, or anger regarding Israel’s actions in Gaza is considered a betrayal of Jewish peoplehood and the State of Israel as a whole. This self-censorship, experienced by so many on the Jewish side, has led to an almost total silence within the art world.

One manifestation of this silence is the widely discussed closure of the Israeli pavilion at the Venice Biennale, accompanied by an explanatory note on its door that reads like an exercise in avoidance—never once mentioning the word war. Since October 7th, the global art community has undergone major ruptures and upheavals—shows have been canceled, committees have resigned, people have been fired, and art spaces have been vandalized. Yet none of these events can compare to the devastation of Gaza and its people. Is silence all we, as artists and curators, are able to produce and exhibit?

The voices condemning the ongoing war are sometimes heard in the Jewish diaspora, yet within Israel, such courage is rarely found—and when it is, it is confined to semi-underground exhibitions. Amidst this climate of silence, a rare exception emerges: the work of Haim Sokol, whose underground exhibition embodies both artistic defiance and historical echoes of suppressed expression.

The irony is palpably painful—his private show, The Victory Museum, has opened in his basement workshop in the center of Tel Aviv, hidden beneath layers of reinforced concrete and steel bars, much like the structures used in war zones across the world, including Gaza. Unlike Gaza, however, Tel Aviv remains intact and alive.

Yet as visitors descend into the exhibition, they are confronted with a suffocating stillness—the deadly coldness of war made eerily close.

Haim Sokol is no stranger to controversy. Born in Soviet Russia, he came to Israel as a young person and graduated from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Later, he returned to Moscow to study at the Institute for Contemporary Art and became one of the most sought-after art practitioners. Sokol lectured at the Higher School of Economics Art and Design School and was a member of the editorial board at Moscow Art Magazine. His solo exhibitions have been shown at the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, and numerous Russian and international galleries and biennales.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Sokol returned to Israel, where he is now based in Tel Aviv. In Russia, the artist explored the dramatic social histories of Eastern Europe, but now his attention is focused on Israel and its fractured identities. Balancing between historical narrative and political allegory, Sokol roots his use of literary allusion in the legacy of major uprisings, revolutions, massacres, and genocides. His works effectively capture experiences of alienation, isolation, and disrupted communication.

Both his recent exhibitions—Bird on the Windowsill (Libling House, Tel Aviv, curators Shira Benyaminy, Anat Levy) and Anichnu (I/We) (Artists' House, Tel Aviv, 2024, curator Hagai Segev)—delved into themes of displacement and estrangement. However, The Victory Museum, which primarily hosts works that could not have been exhibited publicly in official settings, simultaneously revives the tradition of Soviet underground art while transporting the audience into a nameless basement like those that may lie beneath the ruins of Gaza.

One of the most striking installations in The Victory Museum recreates the fragmented interior of a war-ravaged apartment. Concrete-stained carpets and a festive dress hanging on the wall—once belonging to Sokol’s mother—stand as haunting remnants of lives abruptly shattered. This same dress appears in a self-portrait by Sokol, inspired by videos of Israeli soldiers cross-dressing and posing in abandoned apartments in Gaza.

The figure’s unsettling presence—combining a traditionally masculine beard with a flowing blue dress—speaks to questions of identity, disguise, and role reversal in the context of war. The firearm in the artist’s hands directly references violence, while the pink and purple hues on his face evoke physical and emotional exhaustion, even dehumanization. The figure is not quite alive yet not fully dead—almost a putrefying corpse. The raw quality of the painting gives it a sense of urgency, reflecting the chaos and unpredictability of war itself. The piece interrogates how war distorts identity—forcing people into roles they never chose and blurring the lines between victim, fighter, and civilian.

Another self-portrait is made from a stone, roughly shaped like a human head, placed on a dark, circular plate. The surface is painted with a distorted, expressive face, using a mix of colors, including blue, pink, black, and white.

Rusted wire is wrapped around the top, resembling hair or a crown of thorns, adding an element of restraint or suffering. The plate underneath has a rough, textured surface, suggesting decay, erosion, or the passage of time.

The combination of natural, unyielding stone with expressive, almost ghostly painted features creates an uncanny effect, reminiscent of surrealist assemblages. The artist’s distorted face, with its uneven coloring and raw brushstrokes, evokes a sense of fragmentation and psychological depth, recalling themes of sacrifice, martyrdom, and historical or mythical beheadings (such as John the Baptist or Salome). The sculpture exists in a space between life and death, object and portrait, echoing surrealist fascination with hybrid forms and the transformation of everyday objects into unsettling, poetic metaphors.

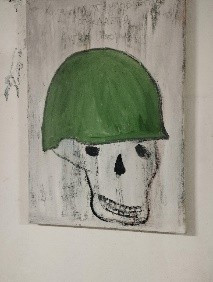

Another Sokol’s painting powerfully conveys the stark realities of war through a simple yet haunting image. The skeletal face, partially obscured by a military helmet, serves as a grim reminder of the inescapable link between war and death. The rough, unfinished quality of the skull, combined with the muted, smudged background, gives the impression of something fading, eroding, or lost—perhaps a reference to the dehumanization of soldiers, the anonymity of death in conflict, or the fragility of life in times of war.

The green helmet, a recognizable military symbol, contrasts sharply with the hollow, lifeless expression beneath it. This contrast can be interpreted as an ironic commentary on how war, often framed as an act of defense or patriotism, ultimately reduces individuals to mere remnants of their existence. The helmet, meant to protect, is rendered meaningless when paired with a skull, reinforcing the futility of violence.

Above the figure, there is faint, handwritten Russian text:

“Когда солдат улыбается, рождается Ангел Истории.”

This translates roughly to: “When the soldier smiles, the Angel of History is born.” This could be an allusion to Walter Benjamin’s concept of the Angel of History, which looks back at the wreckage of the past while being propelled forward by the winds of progress. The phrase may suggest that war is often glorified or justified by those in power, while history itself becomes a tragic accumulation of destruction and suffering.

In the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, this work could be seen as a critique of the cyclical nature of violence, the way war claims countless lives, and how political decisions made by leaders translate into human suffering on the ground. The raw, almost childlike rendering of the skull adds to its emotional impact, stripping away any illusion of heroism in war and leaving only its most brutal truth: death.

Another installation by Sokol evokes a powerful sense of instability, displacement, and destruction—common themes in the context of war, particularly in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The central element, a torn and partially collapsed bag, appears to be filled with a mix of materials, possibly cement or another construction substance. Emerging from it are twisted, wiry branches or barbed metal formations, resembling both roots and shrapnel, a visual contradiction between organic growth and the remnants of destruction.

The structure sits on a tattered, makeshift platform with wheels, giving the impression of forced movement—perhaps a reference to exile, evacuation, or the transient nature of survival in war-torn areas.

The rough floor, scattered debris, and frayed elements reinforce a sense of decay and impermanence.

Behind the central installation, a hanging fabric with a checkered pattern looms over the scene, incorporating faint, ghostly figures. The fabric itself resembles a traditional keffiyeh, a symbol deeply associated with Palestinian identity and resistance. Its presence in the background, coupled with its worn and ragged edges, suggests cultural memory, loss, or the enduring presence of history in ongoing conflict.

In this context, the work could be interpreted as a meditation on displacement, reconstruction, and the cycles of violence. The bag, possibly a symbol of humanitarian aid or construction material, paradoxically spills out jagged, weapon-like structures, emphasizing how war transforms even tools of rebuilding into instruments of destruction. The overall composition invites reflection on the fragility of life in conflict zones, where movement, survival, and cultural identity remain precarious.

Another work that can be interpreted through the lens of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, is the The Skeleton Building, which reflects themes of destruction, displacement, and the haunting presence of history. The decayed structure on the right side of the composition, with its skeletal frame and hollow windows, could symbolize the ruins of homes, neighborhoods, or cultural landmarks lost in the cycles of violence that have shaped the region. The dark, expressive brushstrokes give the structure an ominous presence, suggesting both physical destruction and the psychological weight of conflict.

The left side of the composition, marked by blurred grays and subtle streaks of pink and yellow, may symbolize uncertainty, memory, or a future that remains unresolved.

The abstract quality of this portion contrasts with the defined ruin, perhaps representing the way history fades into the collective consciousness while its consequences remain tangible.

This visual language aligns with artistic responses to the conflict that grapple with themes of erasure, trauma, and resilience. It recalls the imagery of war-torn landscapes but resists direct representation, instead evoking an emotional and psychological terrain shaped by loss and endurance.

In another powerful installation project, Sokol combines a heavily decayed, tangled mass of wires, fabric, and metal—resembling a bird, made of burnt or corroded industrial material—with an old, deflated leather ball bearing visible cracks and stitching damage. The ball is inscribed with the words “Royal Mundial.”

The juxtaposition of these elements creates a stark contrast between organic decay and remnants of past peaceful activity, evoking themes of abandonment, memory, and the passage of time. The setting—an unfinished or deteriorated indoor space—reinforces the ideas of ruin and loss. This composition reflects the fragility of human-made objects and human life in general in the face of relentless war.

Perhaps the starkest installation in the exhibition is the towering Arch of Triumph, another addition to Sokol’s previous collection of arches, which replicates the exact proportions of the famous Arch of Titus, built in 81 AD by Emperor Domitian in Rome. The Arch of Titus has served as a model for similar constructions throughout history.

Sokol has built a wooden framework resembling the skeletal architectural structure of the arch, which can also be interpreted as a gateway or a fragmented building façade. The structure is made of unfinished wooden beams and planks, some reinforced with wire mesh. At its center, an arched opening is partially framed with white and brown panels, creating contrast with the raw materials.

Hanging from the construction are models of dead birds, suspended by thin strings or wires, creating a sense of weight and tension. This unsettling element evokes associations with containment and remnants of destruction. The red-and-white caution tape further reinforces the impression of restriction and danger.

The interplay between architectural elements, industrial decay, and the birds’ corpses symbolizes transience, instability, and forgotten histories. The installation invites viewers to reflect on the tension between construction and collapse, presence and absence, and the true meaning of victory.

In 2019, Dr. Shmuel Harlap published a column on the website of the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, reflecting on an IDF workshop on the meaning of victory, led by then-Chief of Staff Aviv Kochavi. Harlap, who earned his doctoral degree in political philosophy from Harvard University, writes:

“The essence of ‘victory’ can be understood as a state of resolve. Beyond this proposed definition, it is necessary to distinguish between two manifestations of victory: subjective or objective. Subjective victory is cognitive and always subject to individual judgment.

Objective victory is factual and thus is subject to a factual state of affairs, not to judgment.”

(https://www.inss.org.il/publication/what-is-victory/)

This cognitive victory can never be achieved, as both sides will always insist on their own individual judgments and truths. The true artist, as opposed to the propagandist, does not participate in this struggle but serves as a chronicler—capturing desperate cries for help or, as in the case of The Victory Museum, the impenetrable wall of silence.