Great Game For The Orient: Who Owns the Far East?

Вы можете прочесть этот текст на русском здесь.

The political struggle for eastern lands, known as the Great Game, led to numerous colonizations that reshaped the face of Northeast Asia. The history of Russia’s Far East is deeply intertwined with the colonial ambitions of the Russian Empire and the forced transformation of the region’s identity.

The new Atlas project text examines the revision of Orientalism on Russia’s Pacific coast. From colonial practices of conquest, displacement of local populations, and the enrichment of Western museum collections with artefacts from Northeast Asia. To the emergence of contemporary artistic strategies, where artists, leveraging their geographical remoteness from the center, remap the region, amplifying suppressed voices and constructing alternative narratives of the past and present.

Read more in the new material from the Atlas project, with illustrations by Sonya Umanskaya.

The “Yellow Peril” and the Opium Wars

This essay is an invitation to re-examine the modernities of Eastern “Others” through the work of artists and to reposition the Orient by considering the history of settlements in the so-called Russian Far East. Competition between British and Russian Empires for the Eastern lands in the middle of the 19th century, known as the “Great Game”, led to multiple colonizations, among which were Hong Kong by the British Empire and Vladivostok by the Russian Empire. Everyday objects and belongings of the first ethnic groups (or indigenous people) of that land (Tungusen, Nanai, Udege, Oroquen, Nivchen) as well as of original Chinese ethnic diasporas who inhabited those territories are now kept in many European collections, perpetuating the ongoing exoticization in the Western gaze towards the Orient. This is part of the wider problematic discourse of either “settlement missions” of Russian ethnographers towards the “civilizing of the wild people” in the East and North of the continent (such as “discoveries” of land by locally famous Vladimir Arseniev or Gennady Nevelskoy), or of European Christian missions to China for “educating” Buddhists through Catholicism (such as Matteo Ricci). Photos of the Giljakes (indigenous to Far East ethnicity) family reacting to the arrival of the white man, which are kept now in the Vienna University collection, reveal the ambivalent attitude towards the contrived curiosity with which they’ve been observed and documented. In the Weltmuseum, another of Vienna’s ethnological collections, objects from the Amur region appear to have been obtained by the Thuringian businessman Adolph Dattan from his trips to Vladivostok and the surrounding area. Some related objects are kept in the controversial Humboldt Forum, which houses a large part of the ethnographic collections of Berlin. The areas of the Amur and Ussuri rivers in the south of the Russian Far East are now newly mapped by local artists from these territories in order to revisit (almost always indirectly) the complexity of such missions which were born out of settler colonial political objectives.

The Christian missions into China, Russian’s construction of the Chinese Eastern railway and other Western forms of control of Chinese markets (started with Opium wars which led to the mentioned above loss of territories of Qing Empire) led to the so-called Boxer Rebellion, which was anti-Cristian and anti-Western in its nature, and one of which traces in the shape of a German Empire’s recognition badge is kept in the Ethnographic collections of Berlin. This transcultural object may be read as a glorification of German (Prussian back then) nationality which made its contribution in extinguishing the Boxer Rebellion making China to be even more dependent on Western power dominance in the XXth century, resulting even in establishing of German colonies in China.

One of the most controversial stories of the museum object’s disoriented journey and orientalisms of the XIXth century from that region is the looting of the Yuanmingyuan Summer Palace in Beijing. During the Second Opium War in 1860, French and British troops seized the palace and in the following days looted and destroyed the imperial collections, making hundreds of objects eventually ending up in many European museums which are still there up to today. As Wu Hung explains in his book, the ruins of Yuanmingyuan were kept in a ruinous state by the Beijing authorities even during the Cultural Revolution to remain a “mute rebuke” to the West and as a general reminder of the “Century of Humiliation”.

Russian territory is perceived to be a horizontal axis, connecting Moscow with Vladivostok by the Trans-Siberian railway (built to a large extent with Chinese labor), which politically maps the territory after colonization of the East. It was presumably the Russian tsarist failure in the Crimean War (1853-1856) that led to the Russian Empire colonizing the south-eastern shores of the continent, settling Vladivostok as a military sea harbor in 1860 in order to establish its own “new Middle East” and acquire access to the Pacific Ocean through the gulf that never froze. This hunger for the Orient led to the erasure of cultures inhabiting the territory, later called the Russian Far East. Before Russian settlements Vladivostok was part of Outer Manchuria and was called Hǎishēnwǎi (literally from the Chinese for “sea cucumber bay or cliffs”). The reason for this occupation was the signing of the unequal Treaty of Aigun (1858) and then Beijing (1860) during a period when the Chinese Qing Dynasty was weakened under the British Opium War, which in Chinese history is called the “Century of Humiliation.” The trade imbalance in the goods market was one the of main reasons for the British instigation of both Opium Wars. The British and broader European demand for Chinese silk, porcelain and tea was much higher than the demand from the Chinese side for European goods (with the exception of silver), which led to a trade deficit for Europe. The British found a solution by importing opium from their colonies in the Indian subcontinent to China, which soon became a serious problem for the Chinese nation. Opium sold in China was also produced in the Russian Far East in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was done by Chinese drug traffickers, who then smuggled the opium back home for sale there. Opium was also planted in Primorsky krai to be exported further to the western and southern parts of the Russian Empire. As ethnographer Ilya Levitov wrote, “drugs are the first vanguard of the yellow race in Russia”.

But who is actually the figure who owns the east?

The Russian name of the city reflects imperialistic ambitions as Vladivostok means literally “to own the east”. But who is actually the figure who owns the east? Before Stalinist mass ethnic cleansing and deportations the Chinese population of Vladivostok prevailed. They were daily workers, but also worked in agriculture, mining and forestry. In the city they opened many opium smoking and gambling rooms, which may be revisited as another consequence of the Opium Wars. The Vladivostok district where Chinese people lived was (and still is) called Millionka (as if millions of Chinese people inhabited it). A racist metaphor of “Yellow Peril” (the xenophobic depiction of Chinese, Japanese and Korean people as threatening) is rooted in history as an excuse for the Soviet government deporting the entire ethnic group out of the region. The State Archive of Primorsky Krai keeps detailed and somewhat controversial photo documentation of Chinese people living in close proximity, taking morphine injections and smoking opium — which may be read as a depiction of the dangerous (for the newly arrived Slavic population) life of Others which later was used to justify mass ethnic cleansing of the city by NKVD (state security police) forces.

Another “Yellow Peril”, a supposed military threat from Japan, led to the construction of the Vladivostok fortress: a huge military facility, scattered all over the Primorsky region. Having been built at the end of the 19th century for the Russian Empire’s defense on the Sea of Japan, it is now preserved under the local museum’s wing, named by the aforementioned “discoverer” of the region Vladimir Arseniev. Over the last few years, about 50 objects from the fortress have been given museum status and were officially transferred from military possession to the Museum-Reserve “Vladivostok Fortress”. The museum proclaims this as a kind of restitution — the return of the city’s heritage to the citizens of Vladivostok, and through public events at the fortress, aimed at family audiences such as concerts and festivals, the museum, thus, involuntarily aestheticizes the military heritage.

Remapping the Orient

Far-Eastern territories in general seem to be a safe zone for artistic practices from the West-East axis perspective: the more remote you are from Moscow, the less visible you are to the political center of the country. The overview below of specific artistic positions has opened a necessity for bringing another perspective, where Vladivostok art practices should be situated in relation to the Asian-Pacific region. Being isolated in Soviet times by land from Moscow while being open by sea to other countries for maritime and trade purposes, Vladivostok offered the conditions for several unique artistic positions, departing from the borderland and navy port significance of the city. Earlier independently established artistic practices in Vladivostok, such as David Burliuk’s period in the city in 1918-1920 and the “Green Cat” art groups in Khabarovsk and Chita at the same time, as well as the publications of the then influential journal “Tvorchestvo” (“Creation”), can be considered all the more valuable for analysing the role which the “safe harbour” of the Russian Far East played for rebellion movements.

By exploring the multifold practices of contemporary Vladivostok-based artists and their Soviet predecessors, one may witness how political isolation, but also voluntary exile and self-ostracism affected their daily life and practices. Here, self-archiving and displacement in the non-physical and physical realms are emphasized as artistic methods that have remained pivotal for both Soviet and contemporary Vladivostok artists who moved towards “inner migration” and worked by discreetly or physically ostracizing themselves: examples of this include Viktor Fyodorov who worked alone on Bolshoi Pelis island since the 1970s, or an art collective who sustain their artistic residency in taiga forest in the north of Primorsky krai. The Rikorda, Zheltukhina and Reineke islands surrounding Vladivostok have already for decades been serving as places of exile for thinkers and makers of all kinds who are building alternative spaces for themselves. Not only geographical sites may become such spaces — as in Victoire’s artistic speculative practice of the fictional publishing house, which can also be read as a political gesture of creating an imaginary space by its own terms.

Contemporary emerging artists inherited multiplication as a method, such as printing, copying, rewriting and distribution, from their Soviet predecessors. Collecting and archiving forbidden, rare, or marginalized artifacts, as well as self-archiving (such as with “Jeans Notebooks” series by Alexander G. with copies of prohibited in the USSR vinyl covers or Fyodor M.’s archive of stamps with reproductions of paintings by XXth century artists) became practices which turned isolationism into authentic methodologies.

Avoidance of direct opposition, adaptation, escapism and mimicry as possible artistic tactics were also inherited from the Soviet Union period by young Vladivostok artists. But they were not conformist, on the contrary — artists subverted the system, often publicly playing with the canonic rules. Not just hidden, but formally neutral artistic methods also preserve the core of civic values under a safe space. Absurdity and irony (such as in Ilya Z.’s series “Evacuation Plan”) are languages that seek to find an answer towards the question of the land’s ownership, supposing that the territory probably belongs to no one, as it has always been a temporary base for currents of people to arrive and to leave at any time.

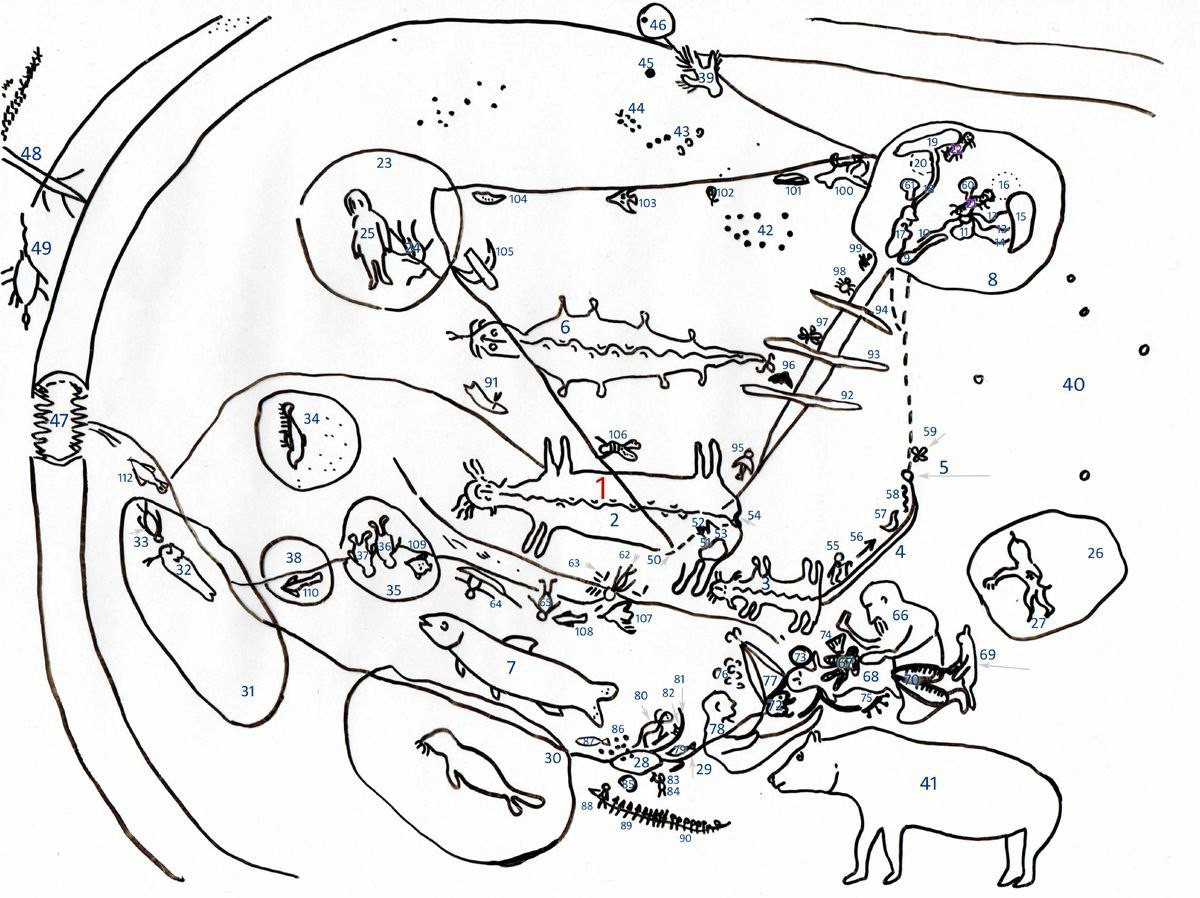

The decolonial remapping is realised by the artists, among other things, through reference to non-obvious or forgotten narratives of place. During his visit to Vladivostok in 2023, artist Konstantin G. addressed the current way of narrative building inside the local ethnographic collection of the aforementioned V.K. Arsenyev Museum of the History of the Far East. His reference was a map hung on the ceiling of the museum, drawn up in 1929 by the Oroqen shaman Sianu (Saveliy Maximovich) Hutunka, which depicts the journey and reincarnation of the (presumably human) soul in the afterlife. An artist K.G. saw the work as an exhibit in the museum and decided to depart from it in terms of both subject and methodology. An ethnographic article about this map was written by state scientists of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in Leningrad. Slavic ethnographers V.A. Avrorin and I.I. Kozminsky traveled to indigenous peoples of Primorskii krai to establish contact with Oroqen shamans near Vladivostok in 1929. They met the shaman Saveliy Hutunka, recorded his map and deciphered it in a 1949 publication from the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, speaking on behalf of the entire Oroqen culture.

To superficially judge these ideas as “primitive” or “naive” means to fit them into the strict framework of positivist scientific knowledge and to repeat Western canonical perception of other cultures as beneath “civilized” ones. Shamanistic knowledge of specific groups, on the other hand, transcends the limits of modern science and mirrors a multitude of cosmologies that are not recognised by the modernist scientific paradigm of progress and civilization. Maps may be equal to oral knowledge as they often weren’t supplemented by any written record. At the same time the map is a visual composition which itself is a piece of art and presumes that it is the first ethnic groups — such as indigenous shamans — who own that part of the “East”.

Maps as a navigational medium and a tool of a dominant scientific knowledge about geography or the structure of the space seem to claim to be an objective document, while their composition or details often reveal a rather subjective time and place, as well as the conditions of their appearance. As researcher Sofya Gavrilova notes in her article “The Lost and Returned Qatar”, ‘“the reverent attitude to the map as the pinnacle of knowledge of the world has its roots in the era of geographical discoveries; due to the difficult exchange of knowledge, they offered their own unique idea of the world picture”. Artist Konstantin G., on the other hand, deliberately distances himself from the authoritarian role of maps in a positivist and modernist framework, and introduces cyclicality into his map as a method of interconnecting all living and nonliving creatures through the questioning of their stable positions. The geography theorist and geographer Boris Rodoman calls maps that are depicted not according to the rules of classical cartography “cartoids”. The remapping made by K.G. is exactly this example of cartoid-making.

The decolonial remapping is realised by the artists, among other things, through reference to non-obvious or forgotten narratives of place

In her essay “Agency and Collections” Clementine Deliss proposes to the call artistic position dealing with ethnographic collections in the museum, a “remediator”: “By assembling new constellations, the artist as a (re)mediator of associations will encourage the object to perform an excess of translation, nourishing clashes and encouraging refusals and revelations rather then allowing the aesthetics and semantic dimensions to fall onto an overriding ostensive definition”. What the artist performs inside the collection (and Konstantin G.’s gesture towards the shaman’s cartoid in the Museum of Russian Far-Eastern history) is the resistance from the ethnographic canons through breaking down non-knowledge and anonymity of the objects, as well as their fixedness in the representation of the past. К. G. repeated the map in his original technique, giving it a new meaning. According to his translation the soul depicted on the map experiencing the post-life rebirth belongs to the red marine algae. To attribute a specific map stored in the museum to an existed indigenous author through remediating it into another image was not an expression of white savior syndrome, as it was criticized by some as a neo-colonial gesture of appropriation, but an animation of the stored object bringing it to a new relation of its position in the history of colonial missions and settlements.

Remapping as a strategy is indirectly implemented by Alexander K., a Vladivostok-based artist who isolates himself on almost uninhabited islands around Vladivostok, such as Rikorda, Reineke, and Zheltukhina. Once there, he maps them by drawing every geographical spot that would help to re-describe these islands, even imitating scientific aesthetics, but accompanying drawings with his non-existing encrypted code language. The tactic of self-ostracizing has allowed the artist to depict lands in a personal way and map the territory by his own means. A. K. practices this writing, encrypting and visual recording as a method for preserving the knowledges of other ostracized hermits whom he personally knows in the form of diaries from plein-air sessions on islands, where he adds rewritings of other oral stories. His drawings may also be read as what Michel de Certeau has called an atlas as a “theater of received tradition and produced knowledge by observers as navigators”, comparing them to “portulans” — maritime maps.