What is the impact of the Women’s Art movement of the 1970s on Modern and Contemporary female artists? The case of Lady Gaga and her 'meat dress'

This text was prepared as an essay for the Art and Design Foundation Program at British Higher School of Art and Design in May 2016 in Moscow.

The Women’s Art movement of the 1970s had a great impact on Modern and Contemporary female artists, such as those from the visual arts, as well as from various creative fields including music.

One of the most pioneering, highly studied and controversial themes that female artists have worked with at different times is the attempt to understand the female body in relation to society in general, and men in particular. This essay will focus on artworks that were made with this topic in mind through the very controversial medium of fresh meat.

In 2010, famous American pop singer Lady Gaga made the headlines for wearing a dress made of pieces of meat together with the meat hat and shoes to the MTV Video Music Awards in Los Angeles (see fig.1). According to various sources there were different messages behind such a courageous act, including an anti-fashion protest, a protest against the U.S. army anti-gay policy and exploitations of musicians and artists in contemporary creative industries. However, considering the topic of this essay, it is necessary to look at this act as at the feministic one — a strong message of not just a popular singer, but a woman who does not want to be seen as a chunk of meat.

The reaction from the media and the public to Gaga’s red carpet outfit was stormy, and just as the dress itself, very controversial — from outraging statements by animal right organisations to admiring comments of Gaga’s fans and fashion epatage lovers. Curious enough, based on my personal research there had been very few attempts by the media to understand the source of the dress and the singer’s act. Most of the public and media thought of the Gaga’s meat dress as an exclusive piece produced solely by and for the singer. However, there are direct references to it in the history of the 20th century Feminist Art, whom the singer and her creative team, including the dress designer Franc Fernandez, might have taken as a starting point for this attention-seeking outfit.

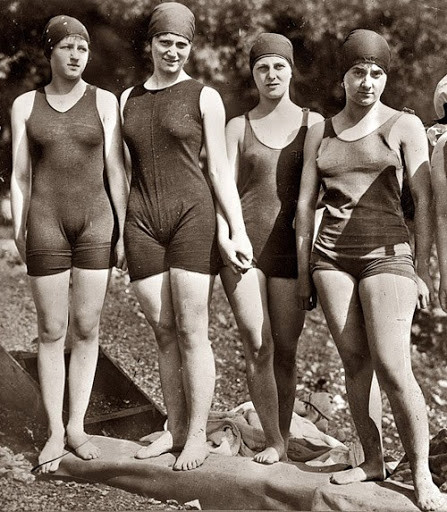

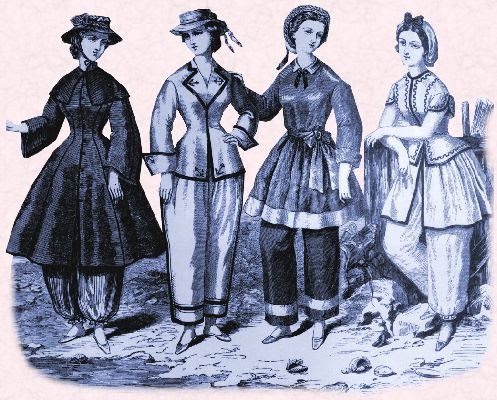

But before tracking those references down it is important to look briefly at the questioning of what is woman and and what is the female body in the feminist movement of the 20th century. Simone de Beauvoir asks, ‘If (…) we admit provisionally, that women do exist, then we must face the question: what is a woman?’. To answer this question the majority of people would probably first of all focus on physical features of a woman like breasts, long hair, her ability to give birth etc. Although these values have existed for millennia due to relaxation of strict social conventions, the postwar Western popular culture has seen a rapid acceleration of this superficial view of women in which physical attributes are valued most highly, certainly more than man. This is most commonly seen in fashion, where swimwear is the most striking example of this (see fig.2.1-2.3). As the result more of the female body started to be seen more often. Naturally, the exposure of more bare skin was equated with flesh — a product to be consumed in a consumer age, much like McDonald’s burger and KFC chicken. During this process the line between sexual appetite and appetite for food became blurred. Indeed, the 20th century scientific studies have shown that there is a direct link in the parts of the human brain that react to sexual arousals and appetite for food.

Naturally these ideas strongly resonated with the modernist art, especially among the female artists of 1960s — 1970s who started exploring the idea of womanhood by itself and oppose to a modernist culture in their works. Working on their ideas through various mediums it is not surprising that eventually some artists narrowed down a representation of the female body directly to raw meat as flesh.

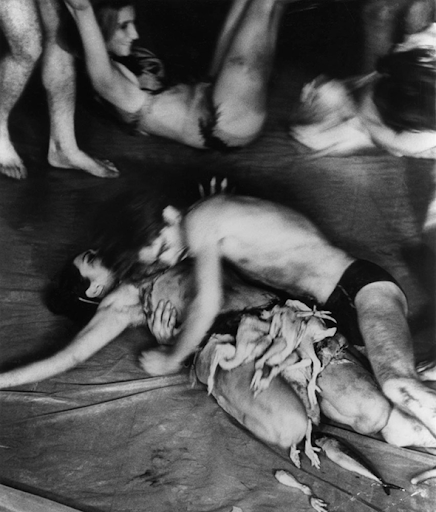

In 1964 the American artist Carolee Schneemann performed her Meat Joy at the First Festival of Free Expression in Paris for the first time (see fig.3). The same year the performance traveled to London and New York where it was met by the audience both with admiration and disgust. Meat Joy is a performance in which a group men and women, stripped to the underwear, dance and roll on the floor intensively interacting among each other while being gradually covered with raw chicken, fish and sausages, as well as paint onto their bodies. The performance was highly sensual and stimulating through touching, hearing, smelling, tasting not only for performers themselves, but due to its’ intensity also for the audiences who found it altogether sexual and disgusting, transformative and unacceptable. This ‘ecstatic group ritual’, as the artist put it herself, was a celebration of the flesh, ‘the character of an erotic rite: excessively indulgent, a celebration of flesh as material…shifting and turning between tenderness, wilderness, precision, abandon; qualities which could at any moment be sensual, comic, joyous, repellent’. Despite the work was not focused solely on the female body, it definitely had a strong and powerful female presence by itself and also in relation to a male body — still it is easily seen that men are dominating in this performance trying to ‘possess’ women by grabbing and biting women, almost eating them. This work can definitely be seen as one of the pioneering ones for the future Feminist Art movement.

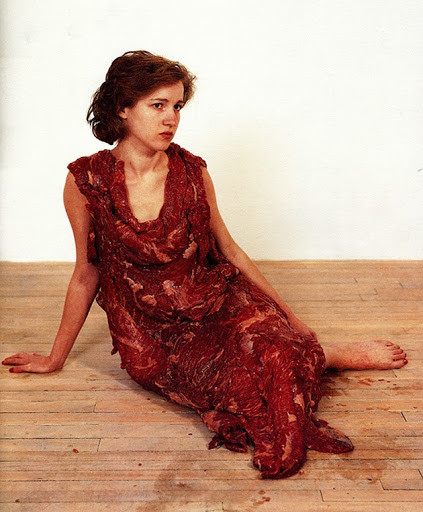

More than 20 years after Schneemann’s Meat Joy, in 1987 the Canadian artist Jana Sterbak produced her Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic. For the work the artist had sewn a dress out of number of meat pieces and put it on her naked body mainly to depict the idea that ‘the body clothed the soul’. Naturally, the dress was intended to dry technically resonating the old meat and fish cultivating processes (see fig.4).

As Sterbak explains in her interview for the Canada Council for the Arts in 2012: ‘There is nothing extraordinary about the making of Vanitas. The meant-drying or the salt-and-fish-drying process has existed for millennia. There is nothing new about it. Maybe the novelty is the fact that I brought the process into the contemporary art scene and into the exhibition space. The message might be strong. And some said that the message, specifically its historical reference might not be understood by everyone. The title Vanitas echoes Renaissance works, in which the passage of time is illustrated by fine details in the painting of fruit, flowers, and by the depiction of rot. These works were intended to remind us that time flies, and that we have to be engaged now. Essentially, this reflection is almost Buddhist. Eventually people stopped paying attention to these paintings, which were mainly found in dining rooms. In Spanish these paintings are called bodegon, vanitas or even momento mori. If this specific work of mine has been seen as having negative connotations or has been perceived as provocative…well, it didn’t occur to me, and it was not my intention, because, for me, the material was simply and concretely expressing the idea of aging, and the passage of time. That’s all’.

As we see, talking about the work even years later after its’ first production, the artist does not mention any feministic ideas behind it. But nevertheless, intentionally feminist or not, the dress was, analyzed by art critics not only as the reference to aging and time passing by, but also as a strong female statement: ’it is a work replete with feminist anger to the objectification of women’s bodies as hunks of flesh. It also represents women’s distrust of their own bodies as commodities that leads to self-fictionalizing and illness’. I would tend to agree with the critics that even if only subconsciously, the Sterbak’s dress reflects the Western’s patriarchal society’s attitude to women in 20th century, and as a result, own women’s attitude to those male perceptions. As stated by John Berger in his ‘Ways of Seeing’: ‘Men dream of women. Women dream of themselves being dreamed of. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at’. Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic is therefore, a striking embodiment of this idea — men looking at women as at pieces of meat in a butchery, and women being very conscious and vulnerable about it, but not having any choice in fact, as their perceptions of themselves is historically tightly connected with their bodies and the male gaze at them. Even the title of the work might suggest that there is a vanity in this — but whose vanity? Apparently of women who like to be looked at, but probably of men, who find vanity in the act of gaze demonstrating their power and superiority by doing so?

Returning to Gaga, this is how she commented on her meat finery in one of the interviews: ‘…it has many interpretations, but for me this evening it“s [saying], “If we don”t stand up for what we believe in, if we don“t fight for our rights, pretty soon we”re going to have as much rights as the meat on our bones”. It might seem to have quite an obvious and superficial meaning, but that is why it is so strong — due to its’ directness and simplicity. The quote by Lady Gaga can be easily referred to the conceptual art works of Carolee Schneemann and Jana Sterbak who in their own pioneering ways reflected on an understanding of the female body and society’s attitude to it. Their reflections the relatively small circle of professional artists , as well as Gaga’s public appearance as a meat chunk are all very crucial and powerful messages that definitely have challenged society in the last 50 years.

Bibliography

Geczy, A., Karaminas, V., Fashion and Art, Berg Publishers, 2012.

Bancroft, A., Fashion and Psychoanalysis: Styling the Self, I.B. Tauris, 2012.

Wilson, E., Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity, I.B. Tauris, 2013.

Feminist Art Book CHECK

Websites and Internet Sources

Denise Winterman and Jon Kelly, BBC, 14 September, 2010, [online] http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-11297832, [Accessed 20 March, 2016].

Ted Stansfield, October, 2015, Dazed Digital [online]

http://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/26217/1/if-you-like-lady-gaga-s-meat-dress-you-ll-like-jana-sterbak, [Accessed 20 March, 2016].

Sandra Frydrysiak, Academia, [online]

http://www.academia.edu/9119835/The_representation_of_the_female_body_in_the_feminist_art_as_the_body_politics, [Accessed 20 March, 2016].

? http://www.caroleeschneemann.com/meatjoy.html, [Accessed 04 April, 2016].

Annenberg Learner, [online]

https://learner.org/courses/globalart/work/133/index.html, [Accessed 04 April, 2016].

Jaclyn Kain, Spoon University, 06 January, 2016, [online] https://spoonuniversity.com/lifestyle/why-your-brain-thinks-food-and-sex-are-the-same/, [Accessed 05 April, 2016].

Bethan Morgan, The Culture Trip, [online]

http://theculturetrip.com/asia/china/articles/fashioning-meat-into-art-carolee-schneemann-zhang-huan-and-lady-gaga/, [Accessed 05 April].

Steve Rose, The Guardian, 10 March, 2014, [online]

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/10/carole-schneemann-naked-art-performance, [Accessed 05 April 2016].

Jillian Mapes, Billboard, 13 September 2010, [online]

http://www.billboard.com/articles/news/956399/lady-gaga-explains-her-meat-dress-its-no-disrespect, [Accessed 05 April 2016].

Films and Videos

Jana Sterbak, 2012 Canada Council laureate — on Vanitas, the meat dress (Canada Council, Canada, 2012).

Making of “Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic” (Lighthouse Films, US, 2012).

Meat Joy (Carolee Schneemann, US, 1964).

Ways of Seeing, Episode 2 (John Berger, UK, BBC, 1972).