Coup+

My weather app is perpetually alarmed:

SEVERE WEATHER: Moderate Low Temperature Warning

It’s + 10° Celsius, March in Berlin.

I laugh but the over-vigilant forecast matches the mood. There’s a lot to be alarmed about.

A friend in the US loses a job as a result of Trump’s executive order decrying “radical-leftism”, a colleague is being forced to resign by a German university — also for her “readical-leftist views”. The two interpretations of radicalism mean something slightly different, but perform the same function. The three of us, having emigrated from countries with active authoritarian regimes, of late find ourselves in a protracted state of deja vu. Meanwhile, in a vertigo of cross-cultural agitation in Berlin and beyond, one can be accused of both being radicalized, and not radicalized enough. It’s been increasingly difficult to discern who is and isn’t an ally, and in what fight, and what “ally” stands for, if anything at all, today.

For distraction, I read an interview with Cate Blanchet, who dodges hard ball questions, and talks about her plan B of working as a Foley artist — if all else fails, she demures. Please, Cate, I think, and push away the screen, getting back to my daily grind. That evening I meet a friend to watch the new hotly discussed documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, which makes a very skillful use of the Foley effects. In the hands of Belgian director Johan Grimonprez, internationally and locally sourced archival materials from the cold war era, are reanimated and given a new voice.

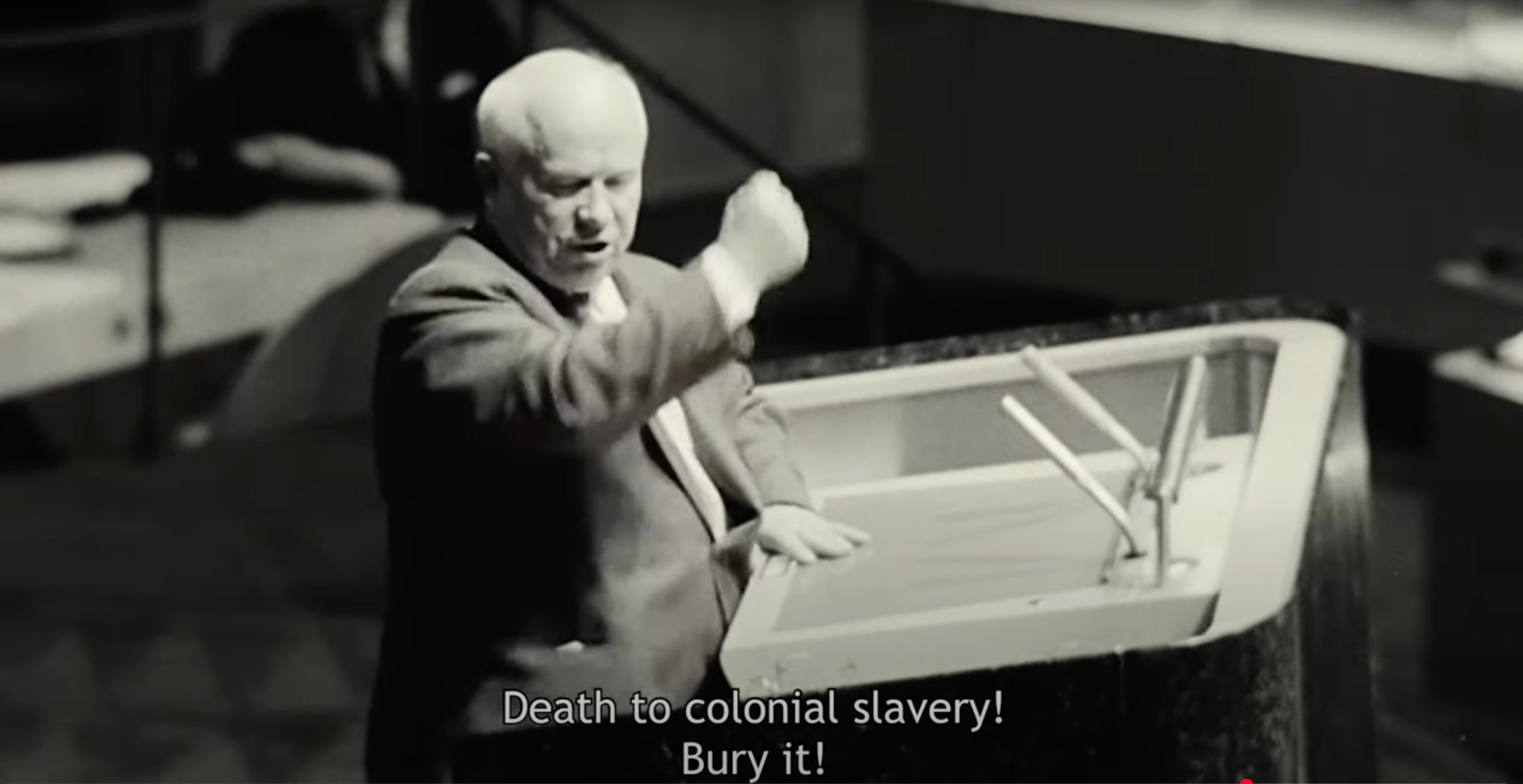

A conductor’s baton whistles sharply, as it slices dead air, orchestra — silent. Politicians and partisans release intimate sighs, and shuffle uncomfortably before the camera; we hear the fabric of a sleeve rub against a table’s edge. Child’s feet patter and echo in a room pregnant with a foreboding sense of violence. Black and white trees of a memory garden woosh, releasing a melancholy oceanic whisper. As the film unfurls over two and a half hours, we shake our heads knowingly, gasp and laugh where appropriate, hide our eyes where the animals are abused, and cringe when Nikita Khrushchev is on screen. The documentary is made to be undeniable: impressive in scope, breadth of covered research, and often in technique (perhaps with the exception of humanly impossible to read one too many slides of text). And yet, I walk out of the cinema perplexed.

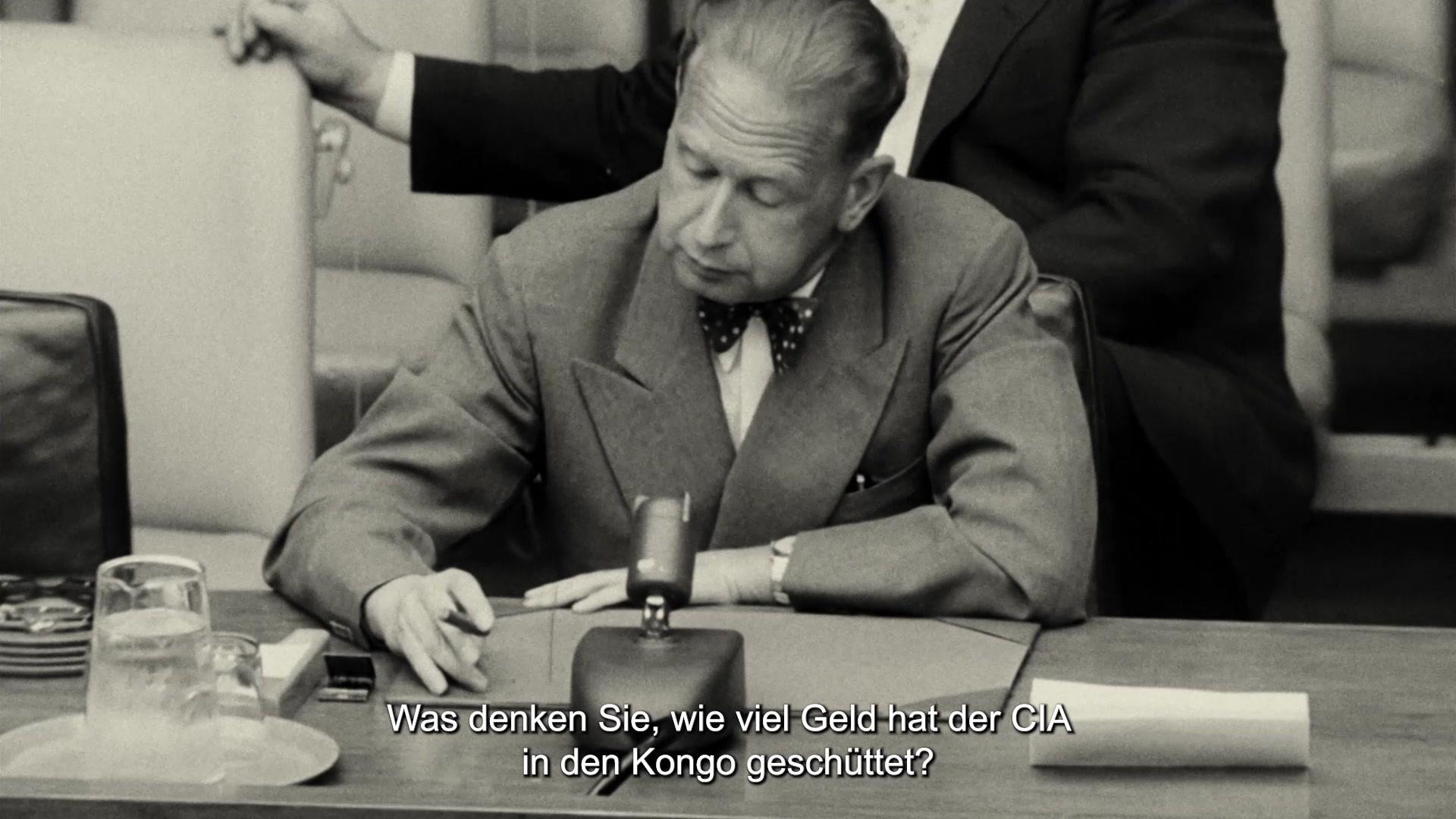

On the one hand, the subject of the documentary is clear enough, if we believe the title: the soundtrack, or the use of “jazz ambassadors” as Trojan Horses by the American politicians, and the hypocrisy in our pockets today, brought home by the splicing of Tesla and Apple ads into the archival footage; the extractivism contained in everyday objects we use, and the direct connection these objects have to the interference in the struggle for self-determination in Africa, by the American and European governments. What perplexes me, is how to take, in the scope of the documentary’s didactics, the slice of Soviet history represented by an abridged portrait of Khrushchev, in contrast to what I know of his fully-fledged persona and legacy. The question is not so much about this film’s particulars or intentions, but the wider epistemic drift within the Euro-American critical discourse, inside of which all things East of Berlin often appear in altered states — blurred, clipped, or distorted.

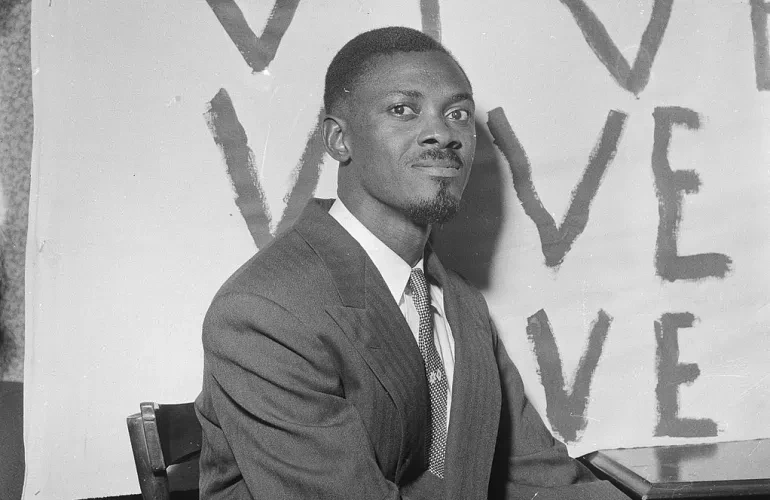

In Theory of a Gimmick, Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form, Sianne Ngai explores the gimmick as a profoundly unsatisfying, and at the same time, revealing, labor-saving device. If so, what kind of labor is saved, or what is revealed, when a gimmick cuts across the retelling of a historic event, in this case the murder of Patrice Lumumba in the 60s? While pursuing its central narrative, Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat does such a thorough job of presenting Mister K. in a singular dimension — as chief decolonial comrade-in-arms at the UN — that it begs for an annotation.

Rather than expanding further the already presented partial view of the documentary, I’d like to focus on the use of archives, to which we as artists, thinkers and public, have (and do not have) access to; and the choice made in voicing them, as related to the period in which this reanimation takes place. I hope, looking at the newsfeed, no one today still believes we can arrive at something like an objective singular view on the past. Rather we look back at archives through concerns of today, and every partial reveal of an episode of history can either illuminate or obscure parts of what present has to say to those of us living now.

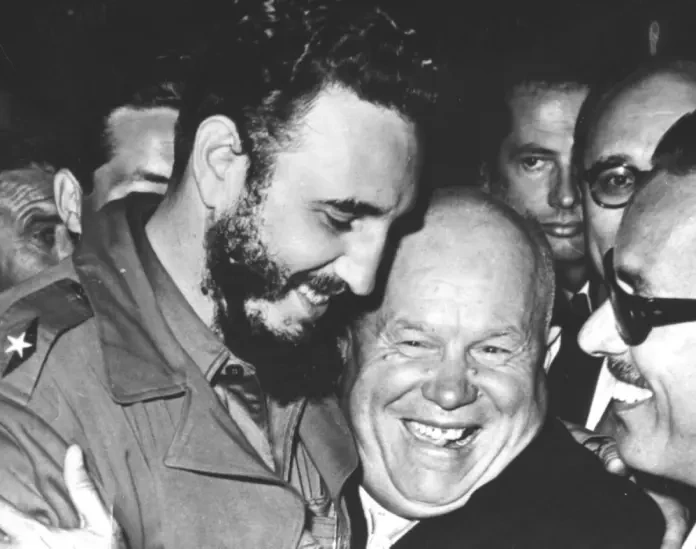

In this case, the gimmick, the Decolonial Manic Pixie Girlfriend — is the bubbling Soviet leader rapping his fist, or fawning over Fidel Castro, with no past and no present, serving main storyline — is a gateway to the hall of mirror that Naomi Kelin so aptly captured in Doppleganger; where, as we watch Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat we might start to selectively remember, and believe that there was such a thing as decolonial Soviet politics, as opposed to a long-dureé battle for spheres of influence and over access to natural resources, also known as cold war. For clues we might want to look to the mercenaries, appearing in a cameo in the documentary, and think about on whose behalf these groups are working today.

African mines, Chinese mines, Canadian mines, check, check, check, Eastern European pipelines and mines, check. Rivera of the Middle East. Human and Natural Resources International. This is the voice of colonial anthropocene —the master of Foley effects — child of enlightenment, modernism, and its post-, merged into a single neoliberal lane. It speaks in tongues, in a myriad of voices, showing a different face to each one who looks. It says: put that suit on, babygirl, you wanted it that way.

The leaders of the Soviet Union, as their European and American counterparts, practiced decoloniality and anti-racism, be it at home or abroad, in name only.

While Nikita Khrushchev might be remembered in the global pop-culture for a certain “thaw”, or the softening of the Soviet Union’s interior and exterior policies during his tenure, in Belarus, for example, he is remembered for a very specific accomplishments, which might, for these purposes, serve as an illustration to my point. The Soviet Union plundered and erased cultures of its fifteen republics installing Russia as the main character, as a continuation of the old European imperial games. “Russian is the language of the future!” — he declared, and banged his fist on the podium, just like he does so very comically in Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat; and then he closed all the Belarusian schools, removed the language from all official use, replacing it with Russian. The question is not merely of language, but of streamlining and smoothing, of speech, practices, ways of life — the straightening of the rivers and drying of seas. This policy was applied to all “minority” or “regional” cultures of the Union to varied degrees of success, averaging the citizenship into white identity, and into Russian language and culture, as its aspirational benchmark. Today, Belarusian autocrat Alexander Lukashenko sponsored by Vladimir Putin continues the tradition of cultural erasure started in the Soviet Union.

The normalization of these practices of erasure in the West — alongside a rather hopeful projection onto the workers-led Soviet Union — can be found in 1972 Audre Lorde’s essay, which she titled Notes on trip to Russia (from Sister Outsider), although she had also traveled to Uzbekistan during her stay, the part of the trip about which she writes extensively in the essay. And again, in a more recent mis-titling, this time of the TV series by Adam Curtis, composed of news footage from BBC archives, and released in 2022, which he called Russia 1985-1999: TraumaZone, despite covering numerous locations across the Soviet — Union. And it is also why, in 2022, the London Review of Books published an essay by Richar Butterwick that referred to Belarus as Belorussia. The naming errors are the products of the centralization and Russification policy in the Soviet Union, and of certain cool indifference to affairs of Eastern Europe and Eurasia in the Western media and cultural discourse, who only felt the need to start reckoning with these subjects after the full scale invasion of Ukraine.

One of the most chilling voices in the Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat belongs to the British intelligence officer Daphne Park, who speaks of an ancient tradition: nothing’s more effective in the art of political interference than simply setting factions against each other, by “gently guiding” them to a collision. This reminds me of a titbit I made note of a while back, listening to the BBC podcast The Coming Storm. In the Episode 5 of Season 1, in which American lobbyist Michael Caputo, who happened to be Trump’s driver on his visits to Russia in the 90s, reminds the listeners that he was initially hired not by Trump, but by the Clinton administration. Caputo also tells us about how he’d acted as a middle man and one of the helpers to gently help inebriated Boris Yeltsin stay in power. He had a familar and ingenious idea of boosting Yeltsin’s ratings by using then popular in Russia musicians as he campaigned across the country. Nautilus Pompilius concerts — brought to you by the US government!

In other words, it helps to spell out that those who were interested in the success of another coup, one that accelerated the crash, as opposed to reform of the USSR, therefore bringing it towards the conclusive resource grab that followed, were (obviously, but it’s worth higlighting it) not what we think of as progressive or leftwing Americans, but — an unholy mix of center-right. And now, the former KGB agent, Putin, ever vegnetful and nostalgic, has taken notes right out of Daphne Park’s notebook: we find her tactics today in that same warped halls of mirrors, diffracted around the globe, and back to the US.

According to Putin, his “special military operation” in Ukraine is a project of anti-colonial liberation. Next to it we have the rebranding of Russia into Russian Federation, which coincided with the invasion, and is the further example of Putin’s version of anti-colonialism — to at once acknowledge who’s the boss and checkbox the federated, therefore, inclusive quality, for all those who might find such things convincing. Dizzying! Meanwhile, whether you do or do not believe Trump is a Russian asset, under his second administration the US has just been brought into the fold of the non-western alliance BRICS+.

There’s more to consider in regards to regrugitations of seemingly progressive theories: the authoritarian appropriation and misuse of anti- and de-colonial discourse, and the emergence of right-wing non-western decolonial alliances, were the topic of a conference held at the Einstein Forum in Potsdam in February 2025. In his introductory remarks, researcher Benjamin Zacharia joked that Global South is located somewhere in North Carolina, inside Duke University Press. With this he suggested that paradoxically, the most attention the voices of Global South receive, is — in the North (also known as the West). I detect further tautology in this global disorientation, where decolonial studies themselves appear to be in need of decolonization. Or, to put it differently, the notion of colonialism today remains only relevant when looked at the intersection with other issues; through longer history and through present state of affairs, both.

I’ve already written about this eslewhere, but will reiterate: in their book The Light That Failed, Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holms observe that following internationalization of English as lingua franca, and with the global ascendance of American culture, American society no longer needed to learn about the world — the world was their backdrop. But the world got to know America, and too well. The authors use this argument as a segway to talk about the paranoid isolationist strategy popularized by Trump, which they see as a backlash to the American expansionism of the previous decades. The anglophone legacy (to use it as summary of effects of two empires, British and American) carries with it a particular kind of epistemic arrogance, which includes not only positions deemed “problematic” but also, critical discourse; its dominance is so naturalized that it is barely noticed by the carriers, of which I am, admittedly, one. What’s been fascinating about living in Germany these past five years, and is reminiscent of my time as a young person in France and Quebec, is that both of these major European cultures attempt to claim marginality inside of the anglophone dominance, as a feature of replacement fears and ressentiment plaguing Old Europe, while conveniently blanking on their own record of cultural supremacy.

Next to it, the continued romanticization of Russia, obfuscation of its history as a colonial actor, and its entanglement with the Western colonialism; and the general lack of knowledge and understanding of the region’s history, manifests today in decisions by Canadian Media Fund, who grant over three hundred thousand dollars to fund the production of the documentary Russians at War. The documentary is made by Russian-Canadian director Anastasia Trofimova, who’s previous record includes work for Putin’s propaganda channel, RT. Even without knowing this biographical detail, one can understand that a woman with a camera, from Canada, living for seven months close with the Russian army and filming the process, is an impossible feat, lest she had the credentials that waved her through, or — perhaps, hired her to make the film?

An expose on the subject of Western endorsement of Russians at War published on Medusa, the Russian independent news website, now headquartered in Riga, reported bleakley: we must understand that the curators of the Venice Film Festival simply don’t know enough about the context. What they see is a well-made film, and reasoning that all sides of a conflict should be represented, they program both the Ukrainian and Russian filmmakers, end of story. Russians at War receives a five minute standing ovation in Venice, and is shown internationally, despite the protests.

Viewers beware of a “well made film”! Where the quality refers to technical means and production value.

This permissiveness extends to more subtle issues, like hiring referred to as “ambiguous” actors, who continue to work in both — current Russian cinema, and appear in the “low-budget” Hollywood productions like the award-winning favorite Anora. Perhaps, given all the problems and opportunism of mainstream cinema (Emilia Perez comes to mind, but there’s more) it’s not even worth paying attention to its machinations. A recent article by Namwali Serpell written for the New Yorker notes the emergence of a new trend in film: New Literalism. I am grateful to the author for giving the problem a name, even if we differ on its application and what it might describe. New Literalism didn’t just happen all by itself. It’s been a long time coming. A side-effect of the information age is an overwhelmed and risk-averse, funding, curatorial, or better said, marketing choices. The algorithmic, gimmicky TV series, films, publications and art exhibitions that make up the core of cultural fare today. What they center always sounds like a meme on Instagram — “about right”.

As I write this, I am aware that how I am perceived, and what credentials I do and do not have, will play a key role in how this text will be received. During the same presentation at Einstein Forum, Benjamin Zachariah introduced another term that I find helpful in thinking about working with transcultural materials today: post-left. This is the left that decrees a variety of perspectives — from racialized, immigrant, marginalized and under-represented positions — as inauthentic, when and if said perspectives do not align with the vetted in, and thus considered authentic, narratives that gladly fall within the discursive patterns of said left, or within a specific diaspora.

It’s clear enough that neither New Literalism, nor epistemic arrogance, or the post-left are going to be helpful in orienting us, whoever this “we” — are, towards the exit out of the hall of mirrors, in which we are presently lost. But, if we choose to listen, the voices of archives might have suggestions.

“We are not pro and we are not against the East! We are not pro or against the West! We are Non-Aligned!” — the archive calls out.