a Thousand Mother Tongues Tree

- Menua who?

- Conversation about mixing and belonging in a not_mother tongue

- Are broken tongues broken?

- Traces of pidginization - linguistic resistance and pluriversality

- Discourse on the Logic of Language

Where are we in the legacy of crusaders?

(make sense of it all in translation)

First, we had to learn each other’s languages.

This was the longest, most loving trial.

Then we undid our own.

— Youmna Chlala, Paper Camera

The Soviet monument named after the Russian emperor in the center of Berlin—Alexanderplatz—is full of people at lunchtime in July. Nearby are a train station, numerous tram and bus stops, and shopping centers. People flow like trout upstream between these multiple transit points. Ani Menua—artist, curator, poet, translator—writes the Armenian alphabet on a shiny totem pole in the middle of the Open Air Museum of Decoloniality. This time, the alphabet began with the word “woman,” which in Armenian is part of the words "sky" and “earth.” We ask passersby to join in this performative poetry. They are visitors of Museum still it open and operates right now in Alexanderplatz. With a pink marker, they can help Ani and write the words “woman”, "sky" or “earth” in their mother tongues. The first ones who came up were three boys around ten years old. One of them responded to the invitation:

“I don’t have a mother tongue,

I only speak German,”

and turned to the third boy, “you write it, you have one.” His friend wrote the word “Maman.”

After these boys, there were more than 150 people who felt it was important to write these words in their languages. Some wrote as requested, others made social translation and wrote female roles—mother, wife, etc. The totem pole was completely filled in two hours. At one point, the metal pole resembled a tree, with so many hands-branches reaching out to add their languages and women and themselves in this performative gesture.

Menua who?

So I choose to read the bird as language and the woman as a practiced writer. She is worried about how the language she dreams in, given to her at birth, is handled, put into service, even withheld from her for certain nefarious purposes. Being a writer she thinks of language partly as a system, partly as a living thing

— Toni Morrison

Ani Menua is an artist, organizer, writer, and migrant. She chose the name Menua for herself. When she meets people who speak Armenian, they are surprised by her deliberate choice of name. It is a male name belonged to one of the kings of the ancient state of Urartu. Ani says that it is easier for her with this name, it gives her the freedom to do what she wants and to be outside the framework of national and gender limitations and requirements.

![Heimatlos poem by Անի Մենուա [Ani Menua] in frame of Voices Otherwise residency by de_colonialanguage in Chto Delat Emergency Project Room, Berlin, 2025](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/6SpQ0-g7klld_U9hA4jeStWmb4nvrct-D7DuSmXf9r8/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzNkZDdjMTBhMzAzYTIwODRiYWVmNGQ3ODk4OWQ0MGM1ZDU4YTc1MGQvc3RvcmUvNWUxMmQyNWQ4YTBiZGZlNzZiM2M3Yzk3MTEwYmUzNzE1ZjA1YWNjNDZmMWI2NjFjMTk1NzM0NjRiOGJhL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

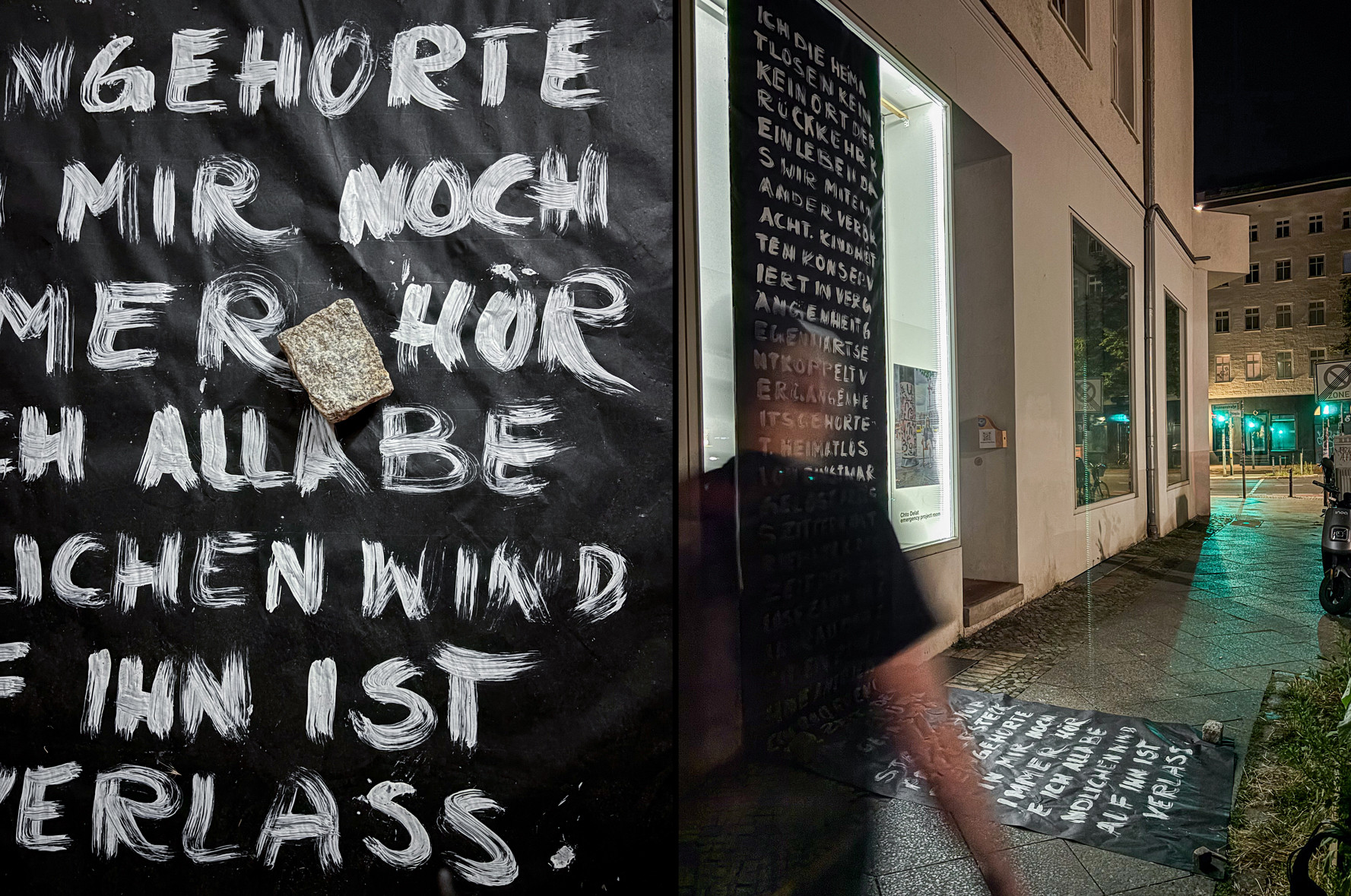

After the Tree of a Thousand Mother Tongues, we gathered at the Chto Delat Emergency Project Room. There is a Signal Window in this place—people send signals to their neighbors to communicate their concerns and invite the neighborhood to cooperate. Ani Menua hung a poem on this window about her feelings of being Heimatlos [keine Heimat zu haben]. Is there an exact translation for this in English? Heimatlos—a person without a home, without a homeland, with a broken sense of belonging. How do you say that in English? And in Armenian? անօթևան [anot’evan]? The poem was so long that it stretched across the street into the sunflowers. It was uncomfortable, loud, disturbing—people stumbled over it. Many people stumbled, stopped, read, came in, asked questions, talked, were silent, left, then back. Home_less?

Then we read poems. Then there was a conversation. Kalmyk poet and decolonial activist Dordzhi Dzhaldzhireev joined us. You can read a condensed summary of this conversation about languages, poetry, and broken feelings of belonging below ~~>

Conversation about mixing and belonging in a not_mother tongue

.work in the fields were one. And then I went to school, a colonial school, and this harmony was broken. The language of my education was no longer the language of my culture. It was after the declaration of a state of emergency over Kenya in 1952 that all the schools run by patriotic nationalists were taken over by the colonial regime and were placed under District Education Boards chaired by Englishmen. English became the language of my formal education. In Kenya, English became more than a language: it was the language, and all the others had to bow before it in deference….

— Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature

![Denis Esakov (de_colonialanguage), Անի Մենուա [Ani Menua] and Dordzhi Dzhaldzhireev in Chto Delat Emergency Project Room, Berlin, 2025](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/9NCETc6f7n9Ns322hmpy5-vXNEhIv1e_fzxciTTx6w0/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzLzA2MmUzNGVjNTY4NmEzNGZjYTBhMTU0Y2YyMThjMjJjODE1NzM4MDMvc3RvcmUvYWU3OWZiYjc5YjFhMzZiNTQxMDZlN2Q5NDQ2ZjJkODJmZjIzM2I5MWU0OWM1NmRmMTlhZWE3NDlkNzllL2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

DE (Denis Esakov): Our conversation concerns language. We listen to and operate in complex mixed territories. Rhythm and national or ethnic thinking intersect in poetry. The question that comes up is, what does it mean to be a Kalmyk poet with Russian language or an Armenian poet in German? Are these categories important? How do you work with languages? What kind of experiments are you performing with languages? How do you apprehend the concept of broken language, and how close is it to your practice?

DD (Dordzhi Dzhaldzhireev): I write in Russian because, first of all, there are very few Kalmyk-speaking people and families in Kalmykia. I come from a Russian-speaking family, although my grandparents understand Kalmyk, but they did not speak it with us. The younger generation does not speak Kalmyk. It was a secret language for us to say things that children should not be able to grasp, to say some other personal things. I learned that deportation had a significant impact on this. From birth, I spoke Russian and was educated in Russian. I realized long ago that it is possible to be published in Russia, in Russian magazines, only in Russian language. There is no publishing space in Kalmyk language. Also, my friends would not be able to understand what I was writing about if I wrote in Kalmyk. That’s the point: first,

there are no opportunities for non-Russian languages.

Even if you write in another language, you will need to translate it into Russian in order to get published. And this shows the other side of the problem: who will read in Kalmyk? Are there any readers of this language? Either you need to produce bilingual publications. I tried to solve this double problem by writing in Russian in such a way as to dispossess the Russian language of its "grandeur". To create a Trojan horse, to write in Russian in such a way as to embed ideas against the marginalization of my people in the texts. So that there would be no place in my poetry for ideas of the superiority of some over others.

I write in Russian, but it is completely different from anything people have ever read in Russian.

My writing carries the identity of a Kalmyk poet, because I consider myself a Kalmyk poet. And it is important for the translator who will translate my poetry to understand this.

AM (Ani Menua): For me, the broken nature of language lies in the fact that here in Berlin I am constantly switching between four languages every ten minutes. And I feel that none of them are mine. German is the language I work and write in, but it is not my language. I am constantly moving from one place to another, also territorially. I developed a distance from everything that people usually feel as a sense of belonging. I don’t really feel like I’m belonging anywhere. For me, the Armenian language is not a national category, it’s a space of language in which I can move and in which I have memories from my childhood. It is a language in which I can communicate with my relatives. Brokenness is the state of a person who is in constant migration. Migration and diasporality are part of the Armenian language. This language is not automatically linked only to the geographical space of Armenia. Armenia that exists today is different from the Armenia that people talk about.

Armenia is not only Armenia, it is a kind of idea about it, and it lies also beyond national territories.

DE: Not from Armenia not from Germany… The sense of belonging is disrupted. It’s a very complex feeling of existing in between. And how are issues of migration and the diasporas experienced in Russia?

DD: I live in St. Petersburg. I was born in a village thirty kilometers from Elista, Kalmykia capital city. And I also felt distant. In Elista, where I grew up, I used to live a very introvert life. I have extensive migration experience. I lived in Moscow, St. Petersburg, the Czech Republic. It was difficult for me to socialize, and I remained in a state of migration all the time. It turns out that I always kept my distance, primarily from my Kalmyk identity. I always wrote alone, I had no community. I was culturally isolated. I experimented and searched for literature. It was very difficult. Everything was done through my own attempts and faults. I had to hide my writing and my aspirations. I did not live in places, but between them. I lived several lives at once. Then all this was revealed when I was awarded the Arkady Dragomoshchenko Prize. People and my relatives began to react positively to my poetry. This reinforced my confidence in the direction of diving into the works of Kalmyk authors. I began to talk about this and introduce it into discussions. To build images of Kalmykia. I want the Kalmyks to be represented among others. I worked hard to develop an image of Kalmykia that would reinforce my Kalmyk identity, which if possible does not conflict with Kalmyk society, the diaspora, or the republic itself.

However, what influenced me the most in forming my identity were thoughts about the Kalmyk diasporas in Xinjiang, Tibet, Kyrgyzstan and other places. These are fragments of the former Dzungar Khanate. I think about what connections can be made. I try to find Kalmyk theaters in Xinjiang, China, the US. There is a diaspora in Moscow, and they are working on their identity there. I communicate with different people who have different positions. We must overcome the division. Poetry helps me with this. I organize festivals, help indigenous poets in Russia read their texts, represent themselves. It is important to resist the marginalization of our cultures. When it comes to Kalmyk culture, it is easy for someone to say that Kalmyks are less intelligent than other Russians or something similar. It is very important to demonstrate that other nationalities in Russia can also write texts, they are equally talented, no worse than people from the metropolia.

I try to speak Kalmyk. Since I was born and raised within the Russian language, I now have to learn Kalmyk, and I try to write texts in it. I try to incorporate texts in Kalmyk into my work. But the problem is that it is difficult to write in Kalmyk, for example, in verlibre (free verse). Or what I write in Kalmyk is immediately superimposed on the literary canon. There is no free poetic writing in Kalmyk without rhyme, based only on rhythm. This is just one example of the broken nature of the language. The continuity of poetic structures in the Kalmyk language has ended. My peers, those who write in Kalmyk, write with rhymes like in other cultures or like their ancestors. Poetic language does not develop further. Experiments like those in the Russian language do not take place. Therefore, contemporary experimental or critical texts do not appear in the Kalmyk language. This severely limits poetic work.

DE: As far as I know, Ani is very concerned that the canon of Western literature does not include Armenian literature. She is involved in activism, translations from Armenian, and expanding the scope of Armenian literature to prevent the ghettoization of culture.

AM: In general, the Armenian language is interesting for German-speaking academia because it is old and has many intersections with the canonical European intellectual field. The ideas of freedom and humanity have long existed in Armenian literature. It is more than 2,000 years old.

The problem is that the Armenian language is perceived as exotic. It is studied by philologists, but it doesn’t interest philosophers, for example. As a result, a lot of knowledge about Armenia is lost.

Armenia is perceived in Germany as a national category. But there is a lot going on in Armenian literature and philosophy beyond the nation boundaries. I strive to make this accessible to people who are not speaking Armenian.

DE: It’s amazing how the discussion just keeps unfolding and unfolding. Obviously, this shows that a lot will be happening in the field of different languages in the near future. And our questions about language and our migrating identities will continue, and there will be even more of them. The fact that we are finding such a space for conversation seems wonderful to me. Let’s take of such spaces and talk more.

Are broken tongues broken?

But who twists my voice? who scratches my voice?

Stuffing my throat with a thousand bamboo fangs.

A thousand sea-urchin stakes.

— Aimé Césaire, Return to My Native Land

Césaire effectively decolonises language by inventing his own French. His endless reinvention of French is also a reminder that whenever the colonised were accused of speaking broken French, they were in fact being broken by the language. They were not ‘scratching’ French (‘écorcher le Français’, as the idiom goes), rather, French was ‘scratching’ their throats, literally, painfully.

— Mireille Rosello, Introduction to Return to My Native Land

Colonial expansion also attacked languages. This is one of the common features of different colonial regimes — western, russian, soviet. Most of them aimed to make the language of the metropole dominant, so that it would function as a lingua franca in all colonized culturally and linguistically diverse spaces. It was not necessarily for the sake of convenience in administration, but rather to erase other epistemologies, to produce identities “convenient” for the metropole, and to homogenize the space. Thus, Algerians were supposed to become French, and Kalmyks were supposed to become Russian. This is how colonial violent chauvinism manifested itself.

Empires and then their successor nation states resolved issues of territorial belonging in such a way that people’s sense of belonging to a particular place was generalized into an abstract “fatherland” and then made to serve the state’s purposes. This did not work out with languages, despite the incredible power and scale of the colonial intervention of European empires (Soviet one is in this list also) in linguistic spaces. People began to mix languages of the metropoles, create their own words and grammatical constructions. Multiple pidgins appeared as linguistic resistance. Pidgin language is a form of contact language that develops between two or more groups of people who do not have a language in common: its vocabulary and grammar are often drawn from several languages and mixed. Fanagalo, Hawaiian pidgin, Wolof pidgin, Kru pidgin, Thai pidgin, Camfranglais, Tok Pisin, Mboko Tok, Nigerian Pidgin, Swahili, and many more. And so Creole language appeared.

In Martinique, language is not a transparent given; it is the locus of continual decisions which are politically and emotionally loaded. No one ever chooses once and for all between French and creole, but the presence of two unequal languages is another of the ideological problems for which the post-colonial subject seems to have no satisfactory solution. In Le créole langue jugulée/ Creole, a subdued language, Dany Bebel-Gisler suggests that a mastery of French is always acquired at the expense of creole. As a result, losing touch with one’s native culture is presented as the price of a successful assimilation into the White world of social success.

— Mireille Rosello, Introduction to Return to My Native Land

Traces of pidginization — linguistic resistance and pluriversality

Pidgin is the language of culture. Rap, poetry, casual conversation. It is not accepted in academia or journalism on an equal footing with national languages. In these spaces,

pidgins are objectified; they are the object of study, but not the language of the researchers. They are not allowed to be the fabric of thought.

Imagine—the language a person has spoken since childhood is not allowed to be the language of thought, research, official speech, or official culture. Yes. This is violence. And pidgin is the resistance.

world that, for nomenclature’s sake, can be called pidginization. As a way of being in the world, pidginization presents a philosophy, a practice that constantly engages with and provokes the prefix "sub-" and has no complex about feeling comfortable in that subterranean, subcultural, and ultimately subversive space. "Sub-" not as in being underneath anything, being inferior, but rather as an undermin- ing of power structures, of language hegemonies, of authoritative systems, of institutional hierarchies, of patriarchal heteronormative structures-all of which come from or are spiced with what the sociologist Aníbal Quijano calls "the coloniality of power.

— Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Pidginization As Curatorial Method Messing with Languages and Praxes

And [here] the question arises:

are there any Pidgins Russian?

[Here] is mental space in which we all understand and agree that the Soviet Union was an empire that succeeded the Russian Empire, which colonized a vast area of North and Central Asia, the Caucasus, and many other lands. In this geographically vast space, an even greater number of different cultures and languages live side by side and are mixing. More than 130 languages. Where are the pidgins?

every national liberation which does not go hand in hand with a radical change of the linguistic superstructure is not a liberation of the people who speak the dominated language but a liberation of the social class who spoke and continue to speak the dominant language.

— Jean-Louis Calvet, Linguistique et Colonialisme/ Linguistics and Colonialism

One example is Surzhyk, a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian used in regions of Ukraine, Moldova, and Russia. The word “Surzhyk” itself comes from the phrase "суміш різних зерен з житом" [sumish raznykh zeren z zhyto] (a mixture of different grains with rye), which reflects the idea of mixing. Linguists may deny that Surzhyk is a pidgin. The Academy tries to declassify this language. And there is street speech from Dagestan, in which some words from the Russian language have been given a local meaning, and visitors from Russia may not understand what the locals are discussing, even if they are familiar with all the words. Language is changing.

![Textile book Әжемнің бал тілі [azhemnin bal tili] (My grandmother’s honeyed words) by Nazira Saduaqas in TAKE aSEAT. MAKE aSHIFT exhibition, Kulturfabrik Moabit, Berlin, 2025](https://fastly.syg.ma/imgproxy/RiQxJW0mSUV_8QaT6BECSYnA-q73NzYbSR6MAZh1Jgc/rs:fit:::0/aHR0cHM6Ly9mYXN0bHkuc3lnLm1hL2F0dGFjaG1lbnRzL2YyNmFjY2Q4Njc2ODEyYjk3YjlkM2EwNDAwNmJkZmQxZDA0Njg4Njgvc3RvcmUvYTgzMDA1ZDY4MTQ1NWZkNTI3YWZlN2JiNjM0ZDE5YzI2MGQ3NjM5YTMxMmZmOGE0ZjBkYjdmZGE4YjE4L2ZpbGUuanBlZw)

There is another wonderful example of such changes of language in the textile dictionary book Әжемнің бал тілі [azhemnin bal tili] by Nazira Saduaqas. “My grandmother’s honeyed words” is how the expression sounds in Qazaq, meaning how her grandmother, in her own way, beautifully and kindly translates Russian words into Qazaq. For example, Nazira’s grandmother called the Russian word ‘холодильник’ [kholodylʹnyk] (refrigerator) “каледнек” [kalednek]. This is an example of phonetic adaptation with elements of folk etymology, characteristic of the Qazaq-Russian bilingual environment, when, for example, the Russian word “chair” in the Qazaq everyday context is reproduced as “krasulia” — with a distorted sound, but understandable meaning. This is how Nazira Saduaqas preserves the memory of her нағашы әже [nagashy әje] (grandmother). And she shows the transformations of the colonial language. I am sure that there are many more such transformations, and despite the resistance of academia and colonial structures, we will soon learn more about existing pidgins.

The argument is that instead of understanding Pidgin or pidginization as a broken version of any language or culture, they must be understood as a gathering of a plurality of languages, lifeways, cultures, philosophies, ways of existing in the world, whereby the gathering is always larger than the sum of its parts.

— Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Pidginization As Curatorial Method Messing with Languages and Praxes

Discourse on the Logic of Language

English is my mother tongue

A mother tongue is not a foreign

lang lang lang language

languish anguish

a foreign anguish

English is my father tongue

a father tongue is a foreign language

therefore English is a foreign language

not a mother tongue

what is my mother tongue

my mammy tongue

my mummy tongue

my momsy tongue

my modder tongue

my ma tongue

I have no mother tongue

no mother to tongue

no tongue to mother tongue me

I must therefore be tongue-dumb

dumb tongue

dub tongued

damn dumb tongue

but I have a dumb tongue

tongue dumb

father tongue

and English is my mother tongue

is my father tongue

is a foreign lan lang lang language

languish anguish

a foreign anguish is English

Another tongue

My mother mammy mummy modder mater meser modder tongue

mother tongue tongue mother

mother tongue me

mother me touch me with the tongue of your

lan lang language

languish anguish

English is a foreign anguish

text, questions and assamblage by Denis Esakov

Das Projekt wird aus Mitteln des Programms des Landes Berlin zur kulturellen Infrastrukturerhaltung und -entwicklung in den Bezirken (Bezirkskulturfonds) gefördert.