Pasolini and Anger against Media Consumerism

At the end of the twentieth century, during a cultural shift and a departure from the epistemological system, cinema began to criticize media capitalism and fascism not just by stating “fascism is bad,” but by creating parodies of media simulacra that were no longer perceived as such. Meta-narratives, the imposition of meaning onto meaning, and parody were the techniques employed by Pier Paolo Pasolini and Kenneth Anger to modify public attention and critique media fascism at the end of the twentieth century, techniques that continue to be recognized in the early twenty-first century.

***

One day, the edict of production, the actual advertisement (whose actually is at present concealed by the pretense of a choice) can turn into the open command of the Fuhrer” Horkheimer & Adorno, The dialectic of Enlightenment

Directors work with the complexity of narrative — for example, Pasolini creates simulations of simulations, constructing a theater within cinema that only pretends to be so. Anger manipulates the mechanisms of social economics, transforming well-known images into consumer products, thus satirically reinforcing them — in simple terms, he flips the semantics and creates a critique of media that may not be immediately recognizable as such. Pasolini’s techniques involve working with history, modernizing it, and integrating historical characters (often from literature, which is also significant) into a context that can be interpreted at any time. Anger’s style lies in overlaying clichés and stereotypical models onto each other to create a highly veiled narrative.

To study this kind of cinema, one needs to look back into history and examine the phenomena that this statement primarily addresses — (media)nazism, (media)fascism, and propaganda that is based on emptiness and functions as a media simulacrum, particularly in the context of the 21st century.

MEDIA SIMULACRA

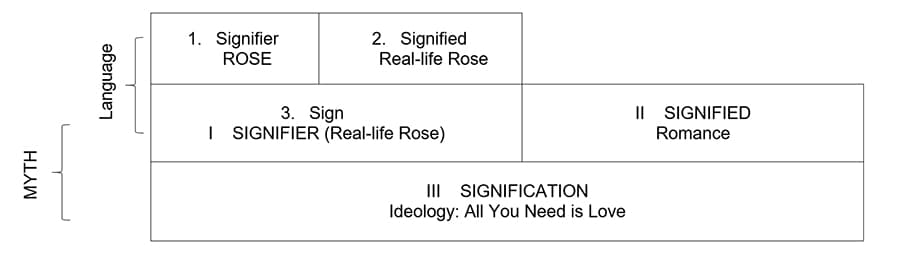

The power of media language lies in reshaping bodies based on the perpetuation of collective consciousness. The influence of media discourse, hidden beneath the veil of the monster, is the creation of standardized bio-technical bodies, as discussed by Donna Haraway in “A Cyborg Manifesto” [1]: “Communications technologies and biotechnologies are the crucial tools recrafting our bodies. (…) Technologies and scientific discourses can be partially understood as formalizations, i.e., as frozen moments, of the fluid social interactions constituting them, but they should also be viewed as instruments for enforcing meanings.” Any text can be considered politicized within the context of the time in which it is interpreted — thus, any mainstream film can be analyzed through the social prism of its influence on the viewer. Political and social codes are transmitted easily, and archetypes acquire recognizable features at an incredible speed. For example, the archetype of a “superhero” is perceived in mass media solely as the image of an American Superman in a costume, representing American patriotism. Initially, Superman did not carry this semiotic aura, but due to media associations, an image was formed that can easily be imposed on any semiotic system [2] — in simple terms, a myth, a sign, and even more so, a simulacrum that carries no semantic value [3] and expands to the point of practical impossibility of its examination [4]. The same can be said for any media discourse: the signified and the signifier merge into one, and then the signifier acquires meaning. In the third semiotic system of analysis, the sign takes precedence.

The unconscious reshaping of the viewer’s consciousness under the influence of media elements can occur in any direction. For example, discussing a film in a cinema, touring an exhibition, or intentional political undertones in cinema — all of these can impact the perception of the medium. Modern war films carry the same subtext as documentaries criticizing environmental pollution and exposing ecological issues. They can create a dual effect: a) “War is a heroic event in which the honor of the homeland is defended”; “War is horror and torment” b) “Environmental pollution is something that can and should be fought through zero waste and the creation of small communities engaged in eco-activism”; “Trying to change the situation with global warming is impossible because we are already on a sinking ship.” In these cases, the viewer’s interpretation and response to the media are influenced by the surrounding discourse and individual beliefs. The complexity lies in the multifaceted nature of media messages, which can be shaped and interpreted differently by different individuals and societal contexts. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari discussed the “metallurgical power” of cinema [5], meaning the ability of the medium to influence the development of contemporary discourse not only within what we consider culture but also in politics, sociology, and economics. This touches upon the field of cultural sociology [6] — the inseparable connection between mediality and the emergence of unconscious cultural structures that impact collective consciousness. Cultural sociology aims to debunk myths and unravel deeper cultural meanings and influences.

There are two intertwined elements — sign-simulacra and (un)conscious transformation of collective consciousness. This can be most easily observed in the example of Nazi Germany and the ethics of fascism and Nazism, which are still relevant to discuss today. This reference is made solely because in the collective consciousness, Hitler’s demagogy has transformed into a sign-simulacrum transmitting the ideas of Nazism. However, it is important to understand how this sign disintegrates under the influence of cultural sociology and the methods employed by Nazi Germany. This understanding helps us comprehend what is happening with mediality at present, within the context of any capitalist obsession, whether it be social, political, or economic discourses.

The propagandistic actions of the Nazi regime include infamous book burnings, radio broadcasts, and the global dissemination of films about Jews such as “Jud SuB” and “Ewige Jud”. The creation of Hitler Youth organizations and politicized women’s associations also played an active role during that time. This active manipulation originated from a socio-nationalist hegemonic system that operated through the influence of signs and indexes, which targeted consciousness at a primary level. These signs were still susceptible to reinterpretation, such as Hitler’s pre-election speeches [7], which could be seen as parrhesia-like declarations (that essentially are rhetorical, not parrhesian, which is crucial in the context of discussing media). This occurred because the signified and the signifier created a fertile ground for self-identification, beneath which there was nothing substantial. In essence, Hitler’s political speeches (comparisons can be made with extensive historical material) contained the potential for unconscious transformation of collective consciousness through the mesmerizing image of the “Ideal Self,” which could supposedly be achieved only by following the political leader.

SELF-IDENTIFICATION

In the late 20th century, the notion of the “ideal self” begins to crumble against the backdrop of the shift from modernism and the experienced crisis. This is reflected in culture, including the cultural turn of the 1970s, when positivist epistemology shifted towards essentialism. Capitalist rhetoric now takes center stage, dissolving the “Ideal Self” without the possibility of self-identification.

Texts in the broad sense of the second half of the 20th century still carry the traumatic affect of World War II and the events of the first half of the century, which set off a chain reaction. The “myths” in cinema at the end of the 20th century ceased to be mere “myths” and started actively participating in changing public discourse — in other words, they became metallurgists guiding cultural sociology. This is what Pier Paolo Pasolini and Kenneth Anger initially engage in, using historical, occult, and literary images for critical debunking. It is not merely about critiquing the media that begins to employ the same rhetorical codes used by radical party politics in the early 20th century (a seeming parrhesia [8] that lacks any foundation — in other words, ordinary rhetoric based on sign-simulacra). It is about the parody of this very media — what Horkheimer and Adorno referred to as the deliberate admission of the status [9]. The film is not simply a film but pretends to be one in order to critically reevaluate the theme, including “metallurgizing” consciousness. The movies of Pasolini and Anger are constructed on the principle of pretense, working to debunk the nationalist-socialist signs and symbols, which this time do indeed carry something genuine beneath them — they are not simulacra; they are mass media, operating in a similar fashion as during the time of Nazi Germany.

PIER PAOLO PASOLINI

Watch list:

Oedipus Rex

Medea

The Decameron

La ricotta

The Gospel according to Saint Matthew

And, of course, Salo, or the 120 days of Sodom

When discussing Pasolini’s critique of capitalism and nationalism, many immediately think of “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom”, one of the most notable nazi-exploitation films of the past fifty years. However, it is crucial to also consider his other works.

All of Pasolini’s films are constructed based on theatrical principles. The director consistently works with the same ensemble of actors, often using non-professional actors. For example, Ninetto Davoli, Pasolini’s lover and his closest person, appears in almost all of his movies. The narrative is primarily built through the plot (plot (literary parable), not the story) and the mise-en-scène. Landscapes and small figurines of people create textual material [10] rather than catering to mainstream cinematic conventions. Pasolini’s communist views are evident in the rhetoric of sexuality portrayed in all of his films, from “The Decameron” to “Arabian Nights.” The bodily liberation depicted in his films is a rebellion of sexuality that is confined within the panopticon [11] of consumer culture. Alongside this, there is a critique of political jouissance [12] in scenes featuring hyperbolized sexual liberation. This ranges from the sadomasochistic abuse inflicted upon the youth in “120 Days of Sodom” to scenes of immoral “animalistic” behavior, such as infidelity in “The Decameron,” where a female character engages in sexual intercourse with a random passerby she meets in a barn. During this encounter, the woman’s face and torso are inside a large pot, completely obscuring her visibility and emphasizing the primacy of bodily presence, which extends to the realm of politics. Political jouissance refers to the acceptance of a regime as a means of self-identification within the political system, as was the case in fascist and socio-nationalist regimes.

“They eat shit” scene in “120 Days of Sodom” can be seen as a literal embodiment of consumerism, wherein the body becomes a sexual phenomenon in its purest form. The motifs of enclosure and confinement, as found in Marquis de Sade’s original work and his own experiences, are transferred to the themes of closed-off spaces within the totalitarian economy of the media, which expands in direct proportion to the global spread of capitalism.

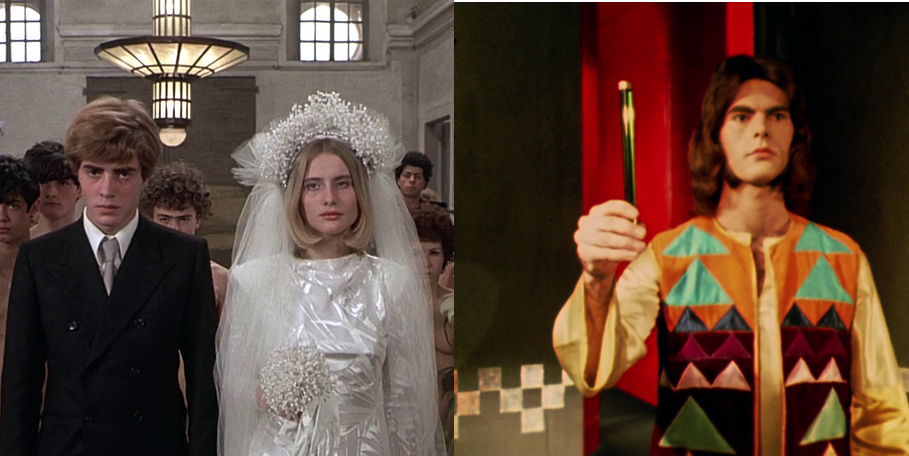

“The Gospel According to Matthew,” “Oedipus Rex,” and “Medea” — all three films are built upon intertextual connections and reinterpretations of the source material. For example, “The Gospel According to Matthew” is a modern adaptation despite using biblical imagery, creating the illusion of a film adaptation while pretending to be one (Adorno and Horkheimer [14]). The theatricality of “Oedipus Rex” and “Medea” involves a double pretense: Pasolini provides 1. The simulation of cinema and 2. The simulation of theater, resulting in the debunking of dual media — both the history of cinema and the history of theater. History is rewritten through the use of old narratives, which can be perceived as ordinary adaptations of literary works. In this sense, Pasolini is a metallurgist filmmaker who works with the fabric of time and reshapes its semantics in a way that can be read unconsciously, solely due to the techniques employed.

Pasolini’s metallurgy [15], aimed at critiquing the consumerism of the late 20th century in the era of an already flourishing capitalism, is not simply a statement of “Consumerism in capitalism is bad,” but a declaration that seeks to expose the loss of identity within endless consumption.

The term “the seduction of innocence” [16] is defined as the influence of public media, in an abolitionist sense, on uncritically organized groups — children, nuclear families, and institutions — on a wide scale. The final scene in “120 Days of Sodom,” wherein the youth, forcibly held captive in the bourgeoisie mansion (an allegorical symbol), brutally and sadistically killed, can be interpreted not as an aside to the phenomenon of “fascism” embodied by mass media, but as a substantive depiction of the disintegration of identity (the violent murder) within the consumerist society that has grown to unimaginable proportions in the 21st century. Media fascism exists apriori, imposed forcefully, even before the existence of a subject, deterministically. The phenomenon of “fascism” as such no longer even exists, as jouissance has fragmented into thousands of parts within consumer culture, escaping political control. Self-identification and the notion of an ideal “Self” in the context of choice are impossible, as they were in the early 20th century. They disappear, allowing themselves to be killed not by a specific regime, but by the accumulation of definitions by mass corporations that exploit them for their own benefit.

Semantic codes become non-objective because, by examining the individual, we automatically include them in the collective, making discussions of individuality impossible.

The power of Pasolini’s discourse lies in his critical analysis of the discourse itself, offering political (and more) critiques of those responsible for distorting semantics and allowing its expansion to unimaginable proportions, where determinative systems cease to function. Essentially, Pasolini predicted the growth of the capitalist monster. His focus on narratives from antiquity and the Middle Ages is not only adaptation, but objectified criticism through comparison.

In collaboration with other directors, a small collection of films was created, including the iconic Pasolini film “La ricotta,” which is constructed in a really simple and not-subtle way by directly exposing the capitalist system and overlaying intertexts. The biblical scenes in La ricotta are the only fragments saturated with color, yet they are staged within the film itself — recursion and ekphrasis. This parallels Pasolini’s parody of the film (a movie which pretends to be a movie) and the painting simultaneously, highlighting their use in perpetuating the system of enslavement within art. The main personification of capital-fascism is transformed through the image of the caricatured director. The central focus of La ricotta is not the crucifixion of the poor proletarian at the end, but the endless attempt to satisfy basic needs within the system (black and white shots, the protagonist running back and forth to cheerful music countless times, causing even the viewers themselves to grow weary), as well as the exploitation of art. “The Gospel According to Matthew” is constructed in a similar fashion, where Jesus is no longer a biblical character but rather a martyr embedded in intertextual connections (black and white imagery being an important distinction in Pasolini’s work). The metallurgist, that is, the director, who can be critically interpreted in the context of time regardless of the socio-political regime, is revealed precisely through Pasolini’s intertextual work. As it was said in the Bible, as it was written in medieval romances, as it was enacted in ancient plays, as it emerged in the early 20th century and as it is still perceived, even stronger than before, in the early 21st century.

The director died in 1975, beaten to death by a group of neo-fascists near his own car in the small Italian village of Ostia, with ten broken ribs, a torn heart, severed ears, and a broken jaw. He left behind an unfinished book, “Petrolio”, and a truly parrhesian statement, the likeness of which nationalists and fascists sought to achieve through their parodies. He did not live to see it.

Throw his bones over

The white cliffs of Dover

And into the sea, the sea of Rome

And murder me in Ostia

Coil, the Death of Pasolini

KENNETH ANGER

Watch list:

Scorpio Rising

Lucifer Rising

Anger’s poetics is a completely different matter. Anger parasitized and satirized parodies not through intertextual overlays, but by creating clichés and parodies within parodies. Anger died five months ago (as I write this in Massachusetts on October 17, 1:37 AM), rebelliously transcending the entire space of film discourse in the 1960s and 1970s, during the height of the cultural turn, while Pasolini was making his films thousands of kilometers away. Anger also works with controlling context, overturning signs, moving away from epistemological determinations of meanings, and toward distortion and the creation of a metallurgical pastiche.

SCORPIO RISING

Exploitation of signs and playing with the parody of attention economy [16] are the main characteristics of Enger’s work. Starting his career as an actor when he was just a child, engaging with Aleister Crowley and being a member of the Thelema, Anger became a director-pretender, creating images within a wide intertextual framework.

“Scorpio Rising” was a film that caused riots across America, offended the sensibilities of anyone it could, and first and foremost, the Nazi Party. The codes are difficult to trace with obscured vision, considering that Anger mainly used non-diegetic perspective, providing a glimpse from the main character’s point [17] of view; musical motifs, symbolism that encompasses almost the entire culture, ranging from occultism to conventional Christianity, and recurring imagery that transitions from film to film (such as the aggressive leather jackets that appear in “Lucifer Rising,” which was filmed later). Anger maintains a tradition of early films in his use of lighting and the construction of action — long, slow shots interspersed with rapid montages.

The image of the melancholic young man is the main dominant in Anger’s films, made during the cultural turn when the traditional understanding of cultural representation shifted from the rationalistic Kantian-Hegelian white male embedded in academia towards “marginalized” subjects (who, of course, should not be reduced to the concept of marginalization [18]) — women, LGBTQ+ individuals, Black individuals, and so on. The homosexuality depicted in “Scorpio Rising” and the vibrant sign-indexes such as motorcycles, leather jackets, and muscular men operate within the attention economy of the 1960s and 1970s, coinciding with the emergence of a new wave in scientific and cultural research and the visibility of queer identities during this time. The group finds a voice, rebels, and speaks out about their own problems (including protests related to the broader understanding of AIDS, which were often ignored). Anger demonstrates, firstly, a play with his own identity, being open and confident about his homosexuality, and parasitizing on the emerging phenomenon not only within the scientific and cultural community but also within everyday life among “mass groups”. Anger’s attention economy involves the exploitation of quasi-material sociological commodities and control over context — the dichotomy of identities. The image of the “melancholic young man” becomes a representative symbol of an oppressed community, constructed through the interplay of stereotypical notions. The same applies to Nazism, which is perceived solely as a violent political act, caricatured through images (sexualized) of aggressive men, buzzing machines, and the overall atmosphere of the film. A dichotomy of beauty and horror emerges, while also toying with the image of Christ, embodying both notions simultaneously.

The media capitalist industry creates a caricatured representation of homosexuality and aggressive acts, disguising itself as both. Homosexuality and queerness are generally portrayed as marginalized, “weak” minorities, as “deviants” [18], while aggression and violence are linked to the face of Nazism (what happens with figures like Hitler as a symbol of Nazism and Stalin as a symbol of socialism in the mass — pointing to specific individuals erases their underlying foundation, and as a result, the recipient of the text only has the models, but not the concepts — this is the power of the media). This conceals media capitalism and media Nazism, which is exploited by large corporations. Like Pasolini, Anger plays with the seduction of innocence [23] because “Scorpio Rising” is essentially a commercial presentation of youth in the 1970s, showcasing its extremes. It also presents the demonstration of consumerism through motorcycles, fashion, and sexual reversal.

Through irony and pastiche, Enger creates a framework of metallurgical storytelling that points to fetishes and popular trends in media, twisting the economy of attention. What they wanted — they got. The viewer undergoes a modification, caught between two extremes that do not coexist with each other. [19]

LUCIFER RISING

HYMN TO LUCIFER

Ware, nor of good nor ill, what aim hath act? Without its climax, death, what savour hath Life? an impeccable machine, exact He paces an inane and pointless path To glut brute appetites, his sole content How tedious were he fit to comprehend Himself! More, this our noble element Of fire in nature, love in spirit, unkenned Life hath no spring, no axle, and no end.His body a bloody-ruby radiant With noble passion, sun-souled Lucifer Swept through the dawn colossal, swift aslant On Eden’s imbecile perimeter. He blessed nonentity with every curse And spiced with sorrow the dull soul of sense, Breathed life into the sterile universe, With Love and Knowledge drove out innocence The Key of Joy is disobedience.

Aliester Crowley

Occultism is something that remains underground and inaccessible to the “common mortals.” From this emerges all the imagery-simulacra of Freemasonry and the Knights Templar, who supposedly control the world. Here again, there is a shift towards focusing on a single enemy image, rather than understanding the phenomenon on which it is based.

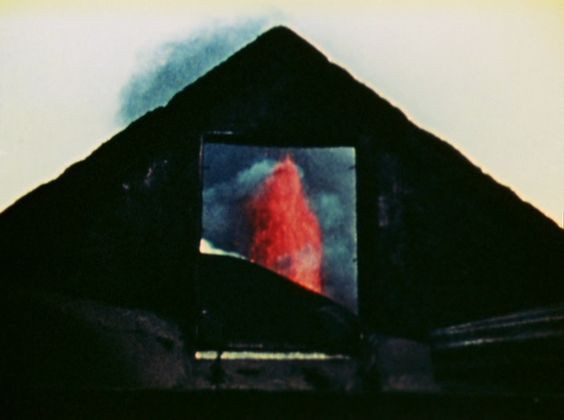

Anger was influenced for a long time by Aleister Crowley and the movement of Thelema, and later in “Lucifer Rising,” he combined his own biographical experiences with the creation of a rift. In the canvas of “Lucifer Rising,” a similar rupture occurs, a schism between two extremes and the creation of a caricatured image, though not as recognizable as in “Scorpio Rising” — violence and beauty coexist, easily interpretable yet not fully understandable, but promoted by media capitalism in stereotypical forms that can easily be consumed by media consumers.

The narrative of “Lucifer Rising” is essentially fragmented, encompassing various chronotopes that span throughout history. It follows the same approach as Pasolini, constructing the storytelling not within a specific historical moment but unfolding it across the entirety of history, allowing analysis through various political and social contexts. Anger similarly utilizes metallurgical shifts in collective consciousness — exerting total control and enslaving the context. Ancient Egypt, contemporary symbols associated with queer media culture (such as leather jackets with colorful inscriptions, the culture of the 80s), the Telema rooms in which the protagonist is immersed — all of these elements become fragmented by time.

“The melancholic young man” once again emerges as the central image, caught between two extremes. Beauty and detachment, the construction of the protagonist’s persona, violence and autonomy — all conveyed through mise-en-scènes and context. The underground is automatically understood as “marginality” — something beyond comprehension and therefore frightening. The traditions of occultism and magic lead back to the Middle Ages, to figures like Paracelsus, alchemy, Gnostic teachings, Kabbalah, and more. In the 1970s, the current practices are automatically associated with what has long become a dualistic semantic representation: the fear of occultism as an aggressive group that can “control the world” (here, Anger draws from his own experiences with occult conflicts and exploitative politics within Thelema, which implied a clear division between neophytes and magicians, a hierarchical ladder [20]), but also the curiosity to understand how it all works. “We will never know in this life if the Masons truly control the world” — from this springs our interest.

Anger utilizes people and groups who represent clichéd images, using them to create a narrative that re-represents them. It’s a parody of representation, a parody of the media. There is constant use of simulacra and genuine symbols to create consumer agency in the discourse. Anger’s characters and plots are open in the sense that they can be filled with any semantics depending on the context, viewer’s self-identification (!), and their inclusion in groups. They are decoded in the sense that anyone who wishes can experience both hatred (for the caricatured representation of their group) and catharsis (through association with the characters and space) simultaneously [21]. The loss of identity is a characteristic of late (media)capitalism — there is nothing to fight for in a battle where identities are multiplied to absurd levels and included in the collective phenomenon of “fascism” which serves as a mere justification [22]. On the staircase of the signified, signifier, sign, and symbol, Anger creates a myth, the final stage of the second semiotic system.

***

Directors of the late 20th century were experimenters, particularly when it came to narrative structures. They created endless historical and cultural paradigms intertwined with each other. As a result, their films, which critique the media fascism of the late 20th century, resonate just as well, if not better, in the 21st century (it is worth noting that Enger lived to see the 21st century with his own eyes). There is a total disintegration of identity and imagery, where even media clichés no longer exist as such, as everything merges into an endless consumerism. However, there is still the possibility for critiquing the media through analyzing 20th-century cinema and its influence on 21st-century cinema.

NOTES

[1] Donna J. Haraway, “A cyborg manifesto” (1985), p.33 university of Minnesota Press

[2] Based on structutalism-period Rolan Barthes “Elements of Semiology” (1964), “Mythologies” (1957), “S/Z” (1970)

[3] “Plato’s definition of the simulacrum is the copy for which there is no original, i.e., the world of advanced capitalism, of pure exchange”; Baudrillard 1983, Jameson 1984 (page 66); Donna H.

[4] Umberto Eco: Persuasive communication; Rhetoric and ideology

[5] Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari “A thousand plateaus” (1980)

[6] Jeffrey Alexander, “Sociologia Cultural” 2002

[7] Address by Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of the Reich, before the Reichstag, September 1, 1939.

[8] Michel Foucault, Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia, 1986

[9] Horkheimer & Adorno, The dialectic of Enlightenment; “a movie that pretends to be a movie”, 1944

[10] Pier Paolo Pasolini also literally uses literary tropes: small landscapes look as sentimental as possible, almost like idylls and eclogues, which are only pretending to be such, like everything else the director portrays.

[11] Michel Foucault, “Discipline and Punish”, 1975

[12] Jacques Lacan, “The Ethics of Psychoanalysis”, 1969-1970

[13] Biography of Marquise de Sade

[14] См. Выше “a movie which pretends to be a movie”

[15] Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari “A thousand plateaus” (1980)

[16] John Fiske, “the popular economy”; Walter Benjamin “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” 1935

[17] the same trope utilized by Noe in “Irreversable”, for instance

[18] It is in the 70s that we can see a shift of queer directors towards re-representation of the community: starting from the stereotypical image (which Kenneth Anger precisely exploits ironically), and pointing not to “marginalization,” they overturn the popular media semantics, indicating not their status of “victimhood,” but their experience and status of non-inclusion, i.e. not oppression from an external “enemy,” which was the focus of all the films.

[19] Boris Groys, Communist Postscript (2006): truth exists only between two theses and cannot be apprehended logically.

[20] The Holy books of Thelema, Aliester Crowley, 1983

[21] The popular economy; Roughly speaking, people are presented as clichés and a parody of human beings.

[22] see above about the images of Hitler and Stalin.

[23] The seduction of innocence, Fredric Wertham, 1954