Hello, dear country! – the Marukis in the USSR and Russia

[Russian version]

Introduction

This text develops the once published material in Russian ‘Torment of Creativity. About Japanese artists Toshiko and Iri Maruki in the USSR", presenting a steroidal version of the previous article. Here and in more detail the event component connected with the Marukis in the USSR and Russia is reflected, all texts of Toshi are touched upon, and also the full bibliography that would concern these Japanese artists is given.

Many thanks to the staff of museums in Irkutsk, Kurgan, Novokuznetsk, Saratov, Samara, St. Petersburg, and to the staff of the library in Armavir for providing materials and information that facilitated the publication of this article. I would also like to thank N. A. Levdanskaya from the Primorsky State Art Gallery for our common interest in the Marukis and their creative heritage. Special mention should be made of the staff of the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels, Okamura Yukinori and Iwasaki Yumi — I thank them for our conversations, the wonderful images of the drawings they provided for this article, and our attempts to catalogue and discover the Marukis' art outside Japan.

Hello, dear country! — the Marukis in the USSR (1937-1967)

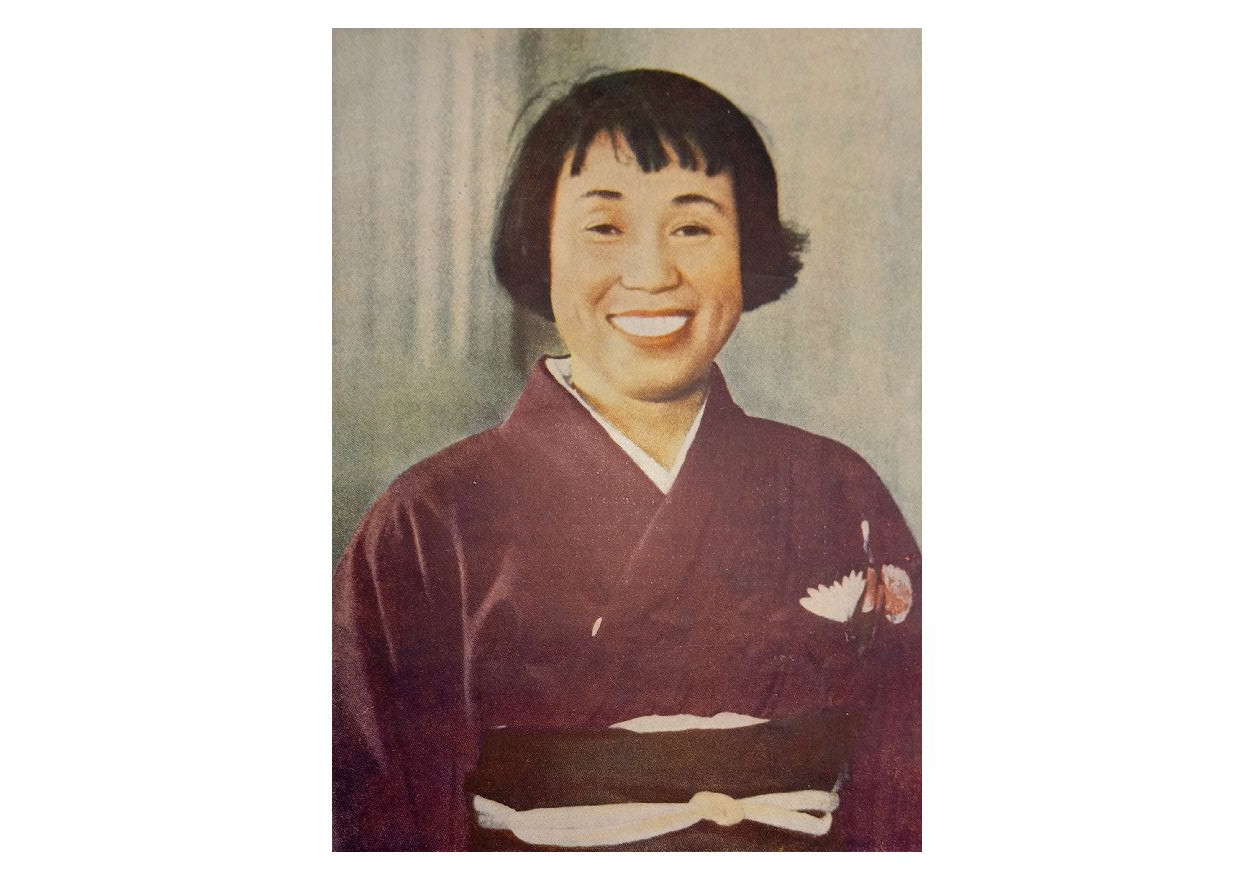

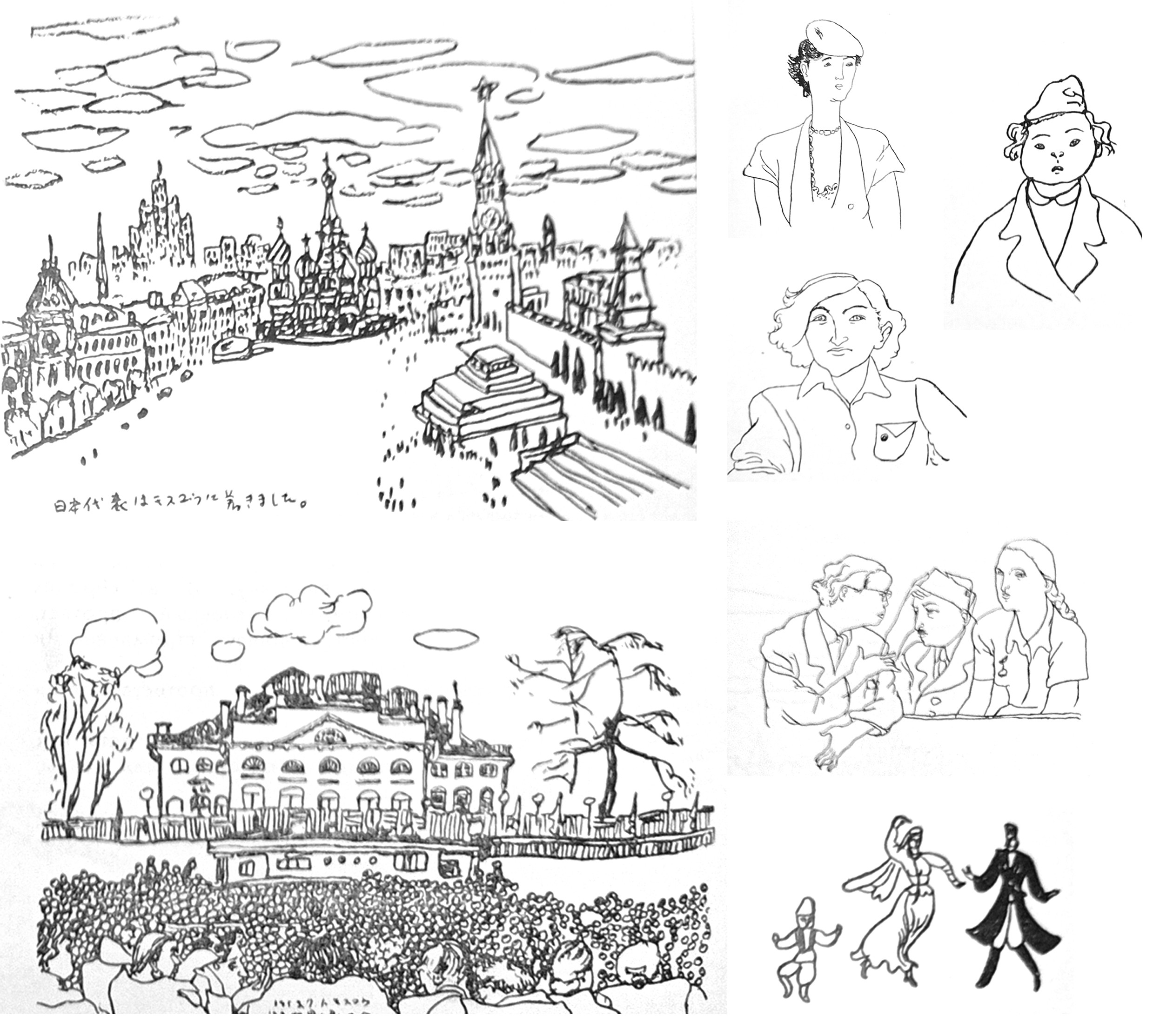

Akamatsu Toshiko’s [1] first visit to the USSR was from April 1937 to March 1938, not for artistic purposes, but as a governess to the children of Shigeto Yuhashi, a Japanese translator. Her second visit to Moscow was from January to June 1941, where she continued her work as governess, but for the daughter of Minister Haruhiko Nishi. During these relatively short trips, the artist visited the Tretyakov Gallery and the State Museum of Modern Western Art, and made some graphic sketches of Moscow everyday life.

In 1953, Maruki Toshi made her first post-war visit to the USSR as part of a delegation of Japanese women [2]. The delegation visited institutions dedicated to motherhood, saw the ballet "The Bronze Horseman" at the Bolshoi Theatre, and took part in an open-air women’s rally where Maruki Toshi was able to meet the politician Oyama Ikuo and his wife. There were also visits to the ballet in Leningrad, trips to Yerevan and Tbilisi, and meetings with artists in Yerevan and Leningrad [Akamatsu 1953, p. 45-47].

In November 1956 [3] there was already a paired trip of the Marukis at the invitation of the Soviet Committee for the Defence of Peace and the Organising Committee of the Artists' Union of the USSR. The exhibition, as can be understood from the press, was shown to a limited number of viewers, mainly the art community. The space for the exhibition was the halls of the Moscow Organisation of the Artists' Union of the USSR, according to one information preparatory drawings, about five hundred, for the Hiroshima panels were shown [Samoilo 1956, p. 3], according to another, three panels, photographs of the rest and part of the sketches [Guests from distant Japan 1956, p. 4]. During this visit, the Marukis visited the Tretyakov Gallery, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, as well as exhibitions and studios of Soviet artists.

In late 1957 the Marukis were invited to the USSR to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Academy of Arts. This trip to the USSR was complicated by the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s obstacles, refusing for a long time to issue visas to the couple. The report of the translator, Julia Cherevko, who accompanied the artists, indicates that the artists underwent a radiation sickness examination, which they specifically requested because they were worried that their visit to Hiroshima could have caused damage to their health. It is also known that the artists were confident that they would be able to sell the gems in Japan at a high enough price, so in the company of an interpreter they wandered for a long time along Gorky Street in the hope of buying a diamond ring. The results of the examination were good, but the diamond ring could not be found that easily in Moscow in 1958 [4].

From the record of conversation with I. N. Tsekhonya, an employee of the Soviet Embassy in Japan, held in March, it is known that Maruki Toshi reported that during her conversation with the artist P. P. Sokolov-Skalya she had roughly determined that the display of the series of panels would take place in August 1958. She also mentioned that she did some propaganda work in Hokkaido, where she and her husband talked about the achievements of the USSR, showing diapositives obtained after a trip to Moscow. There was also a discussion concerning the creation of an international magazine in defence of realism, an idea she had heard about from the Minister of Culture, N. A. Mikhailov. At the end of this conversation, the artist requested that the books be given to the Soviet-Japanese actress and film director Okada Yoshiko [5].

The first full-scale exhibition of the Hiroshima panels took place in 1959. The exhibition was organised by the international commission for the exhibition of the Hiroshima panels, which included the director of the Amsterdam City Museum V. Sandberg, sculptor J. Havermans and others. On the Soviet side, the Soviet Committee for the Protection of Peace was in charge of organising the exhibition, during which a series of ten panels and ninety drawings were to be shown [6]. The Soviet side was to be responsible for the transport of the works as well as their insurance [7].

The organisation of the exhibition was accompanied by long negotiations; the National Peace Committee insisted on holding the exhibition in the USSR, but it was additionally pointed out that holding it in Moscow would be detrimental to exhibitions in the non-socialist world [8]. In the end, the dates and the exposition route was determined by the Artists' Union of the USSR (Moscow, Leningrad, Stalinsk (currently Novokuznetsk), Irkutsk, Novosibirsk [9]), and the opening was planned in the exhibition pavilion in the Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure (Moscow). In the 1950s, the panels were not yet arranged as they are today; the works were rolled up and unfolded as individual sheets. This was originally to make them easier to transport and roll up, including during the Marukis' exhibitions in Japan during the American occupation, where it was reasonable to do so for censorship reasons.

The display of the Hiroshima Panels in 1959 was accompanied by an impressive amount of press coverage that emphasised the importance of the exhibition and the social significance of the Marukis' work [10]. Reviews of the exhibition among Soviet audiences in all cities expressed solidarity with the Marukis' artistic statement, but in Moscow there was widespread dissatisfaction with the exhibition pavilion in the park, the lack of guides, and the incorrect order in which the works were displayed:

"To put such an exhibition in the park (indecipherable) is an outrage and disrespect to such wonderful works of modern art" [11].

"Why is this exhibition not in the Manege? [12] After all, this building was specially equipped and adapted for such exhibitions. To bring this exhibition here is an insult to the authors and a direct detriment to the propaganda of the cause. Peace!" [13]

"The exhibition is poorly displayed. The panels of great artistic value and political orientation would have reached the viewer better if they had been placed in the order the authors thought, not mixed up" [14].

"The sluggishness of the organisers of the exhibition is astonishing! It is clearly not sufficiently described in the press. The people don’t know enough about it. There are no qualified guides at the exhibition" [15].

The vast majority of the feedbacks had an anti-war and anti-nuclear message, expressing humanity’s fear of war and destruction, and many viewers expressed their gratitude to the Marukis for showing their work in the USSR. A number of reviews called for the US to be held responsible for the bombing [16], while others wanted to honour Khrushchev’s achievements in building a new world [17].

The Marukis were present at the opening of the exhibition, and it is known that during their visit they donated prints by various Japanese masters to Soviet museums [18].

"We are escorted into the exhibition pavilion. Immediately we find ourselves surrounded by visitors. The eyes of the encircled people are burning angrily. You feel a kind of fear: is not their anger directed at you? But it’s not. — Can’t we get the cursed one banned? How dare they do such a thing? To destroy innocent children. I am strong, but I can’t hold back the lump in my throat either. Hugging each other, we cry together” [Maruki 1959, p. 44].

During the exhibition, a mass rally was held to ban nuclear bombs and wars around the world [19]. At the end of the rally, the Marukis and other participants decided that the books with the signatures of the visitors should be sent to Stockholm, but this was not done. On 25 June a meeting was also held with the artists and a delegation from the “Japan-USSR” Society [On Exhibition Halls 1959, p. 80]. After the opening of the exhibition and related events, the couple spent time at the House of Creativity on Senezh Lake, where they communicated with Soviet artists, and Maruki Iri even posed for them during a practice session [Maruki 1959, p. 45]. It is known that the artists attended the performance "Stolen Life" at the Mayakovsky Theatre [Samoilo 1959, p. 2]. They also paid a visit to the State Museum of Oriental Cultures, it was reflected in the photo, where the Marukis looked at the painting "Mount Fuji in May" by Yamamoto Ogetsu [Interesting Exhibition 1959, p. 4].

"For us, the Soviet people, the Hiroshima Panels are especially close and understandable. Who else but our people, who endured incalculable suffering in the past war, who won victory at great cost, can understand people’s desire for peace, for a happy and radiant life! The bitterness and sorrow of the past make the struggle for peace, led by the Soviet Union, even more resolute and persistent" [Koretskikh 1959, p. 4].

"They took an oath to fight to ensure that the Japanese people would never again be deceived and plunged into a war of aggression against their great neighbours, the Soviet Union and the People’s China" [Tsehonya 1953, p. 4].

In February 1960, the exhibition reached Novosibirsk, which, as can be judged, took place thanks to the acquaintance of the chairman of the board of the Novosibirsk branch of the Artists' Union of the USSR, M. A. Mochalov, with the Marukis, during his trip to China [Fonyakov 1960, p. 4]. The exposition repeated the Moscow exhibition; a series of panels and 100 drawings were shown in the exhibition halls of the Novosibirsk branch of the Artists' Union of the USSR in a similar manner [Hiroshima will not be repeated! 1960, p. 192].

The Marukis' initiative to organise a solo exhibition of Tomoe Yabe appears in the documents of April 1960. It was positively received by the embassy, but with a strong recommendation to go beyond solo exhibitions and to favour group exhibitions [20]. Tomoe Yabe’s letter to the Ilya Ehrenburg [21] and his wife revealed that it was the Marukis who had asked the general secretary of the Artists' Union of the USSR, D. Suslov, to help fulfil the artist’s wish and allow him to visit the USSR [22]. By July of the same year, there was no response regarding the Tomoe exhibition, with which D. Suslov rushed the Soviet side, but the idea of holding a Tomoe exhibition [23] was eventually abandoned in favour of a group project. In September 1960, negotiations began at the embassy, in which the Marukis continued to participate, proposing artists for the exhibition. In October 1960, a meeting was held between the artists (the Marukis, Yoshida Tadashi, Nagai Kiyoshi, and Nakatani Tai) at the Marukis' home. Discussions took place concerning the organisation of an exhibition of contemporary Japanese realist artists in the USSR. The Soviet side declared interest in both proletarian artists and "bourgeois" realist artists. No specific authors or works were announced.

Discussions about the exhibition [24] continued in January-February 1961 with consul G. E. Komarovsky [25]. The financial issue was most acute, with the artists (the Marukis, Tomoe Yabe, Okamoto Toki) insisting that they be paid for their works, as they seriously feared the consequences of the exhibition in the USSR for them and the reaction of the United States. They were concerned about whether the Soviet side would purchase the works within the four million yen (ten thousand forty rubles) limit so that they could cover the cost of the ten-person group’s stay [26].

In October 1961, another meeting was held between G. E. Komarovsky and the Japanese artists (the Marukis, Tomoe Yabe, Okamoto Toki). As a result of the discussions, Artists' Union of the USSR was ready to invite only one Japanese artist for a month, although the exhibition itself had about 100 participants. The Japanese side continued to insist on the allocation of funds for the trip of ten people to the USSR [27].

On 13 December 1962, the Marukis visited D. E. Komarovsky at the Soviet Embassy, where a meeting was arranged with Suzuki Kenji and Ueno Makoto. The Japanese side expressed dissatisfaction with the partial display of Soviet graphics, poor publicity of the event and lack of press coverage. This was due to the internal disorganisation of the Japan-USSR society and the clarification of relations regarding the exposition, as well as the delay in the printing of posters and postcards. Additionally, the artists complained that since the exhibition of contemporary Japanese graphic art was organised in the USSR, the participants had not received catalogues and posters, and were unaware of the audience’s reaction and the number of visitors. According to the artists, this put them in a difficult situation, as they knew that in the USA the situation for Japanese printmakers is much better: there is interest, the possibility to exhibit and sell their works, not to mention the support from foundations and various organisation [28]. Two weeks later there was another meeting to discuss the exhibition of independent artists, but the Marukis were more concerned that they had not been notified of the start of the second congress of Soviet artists, although they had been invited earlier. The Marukis felt that the Soviets thought that the artists were not doing enough to strengthen cultural ties, which was the reason why invitations to the congress were not issued. This was particularly upsetting for Maruki Toshi, as she had planned to make arrangements at the congress with artists from South America to exhibit her work in those countries. As it follows from the documents, the error was more of an organisational nature, and there was no reason to refuse the Marukis' visit. Lastly, the issue of material against abstractionist artists was discussed, as well as, according to Maruki Toshi, the need to invite new masters of Japanese art (Kawabata Ryushi, Higashiyama Kaii, Hiratsuka Un’ichi, Kitaoka Fumio) [29].

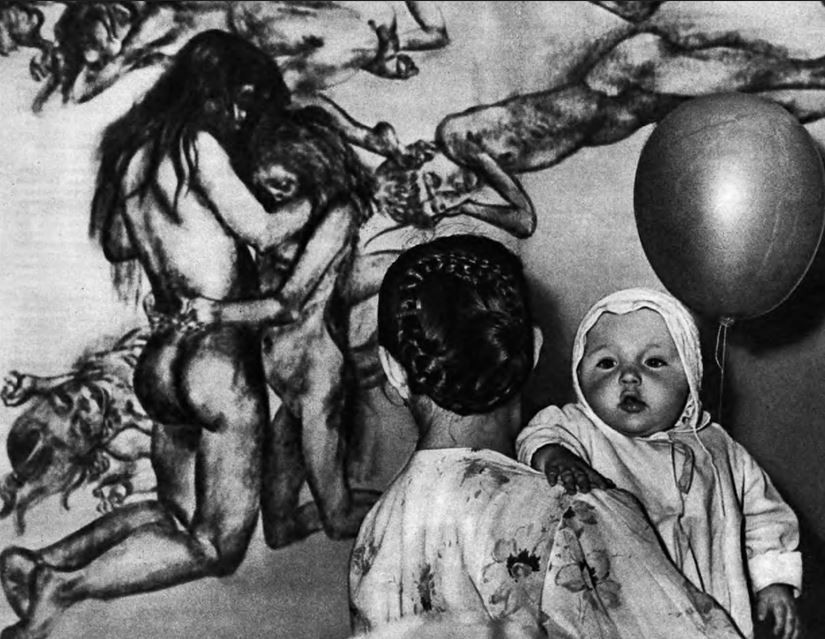

At the exhibition "Modern Painting in Japan" (1962), which the Marukis helped to organise, a part of the panel "Women and Children" [30] was shown, as well as Iri’s "Volcano Asama" (1958), "Fuji in the Clouds" (1958) and "Bulls" (1949) [31]. Toshi had "Victims" (1960), "Demonstration with Lanterns" (1960), and "Demonstration in the Rain" (1960) shown. A catalogue was published for this exhibition, where the authors of the introductory text were Arai Shori, Maruki Iri, Okamoto Toki [Modern Japanese Painting 1962, pp. 3-4].

In December 1964, Maruki Toshi was invited to the USSR by the “USSR-Japan” Society as part of a women’s delegation. As part of her trip, she wanted to expand the creative exchange between women artists, as well as to create a series of works on the theme of Russian ballet and motherhood to then be shown in an exhibition in 1965. She noted that two exhibitions could emerge from these plans: either an exhibition of portraits of Soviet women or an exhibition of views of the USSR. It is also known that she made a donation of one painting, which was sent by the steamer "Baikal" to the Artists' Union of the USSR. At the same time in Moscow, Maruki Toshi’s niece, Oda Kyoko [32], was studying folk song at the Tchaikovsky Moscow State Conservatory [33].

In January 1965, the group of soviet artists (E. Belashova, A. Lebedev, V. Tsigal, and M. Aslamazyan) held a meeting with Maruki Toshi, who was in the USSR through the Union of Soviet Societies of Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries. In the course of communication, they discussed the possibility of creating an international organisation of realist artists, which would serve to create an artistic ensemble in Hiroshima. The Artists' Union of the USSR also extended Maruki Toshiko’s stay for two weeks [34].

According to the memoirs of art historian A. Kolomiets, the Marukis were in the USSR in the summer of 1965 [35]: "Once in the summer of 1965, being in the Soviet Union, on Senezh Lake, in the House of Creativity, he demonstrated the technique of national painting, drawing with ink and brush, spreading sheets of thin rice paper right on the grass. Then all those present were amazed by the precision of his hand, fantastically honed technique and skill of this artist, able to create an image full of impressive power and expressiveness with one stroke of a line, stroke, spot" [Kolomiets 1968, p. 44]. In the autumn of 1965, there was a short correspondence between the Marukis and M.V. Nesterov, chairman of the board of the “USSR-Japan” Society, discussing plans for cultural cooperation [36].

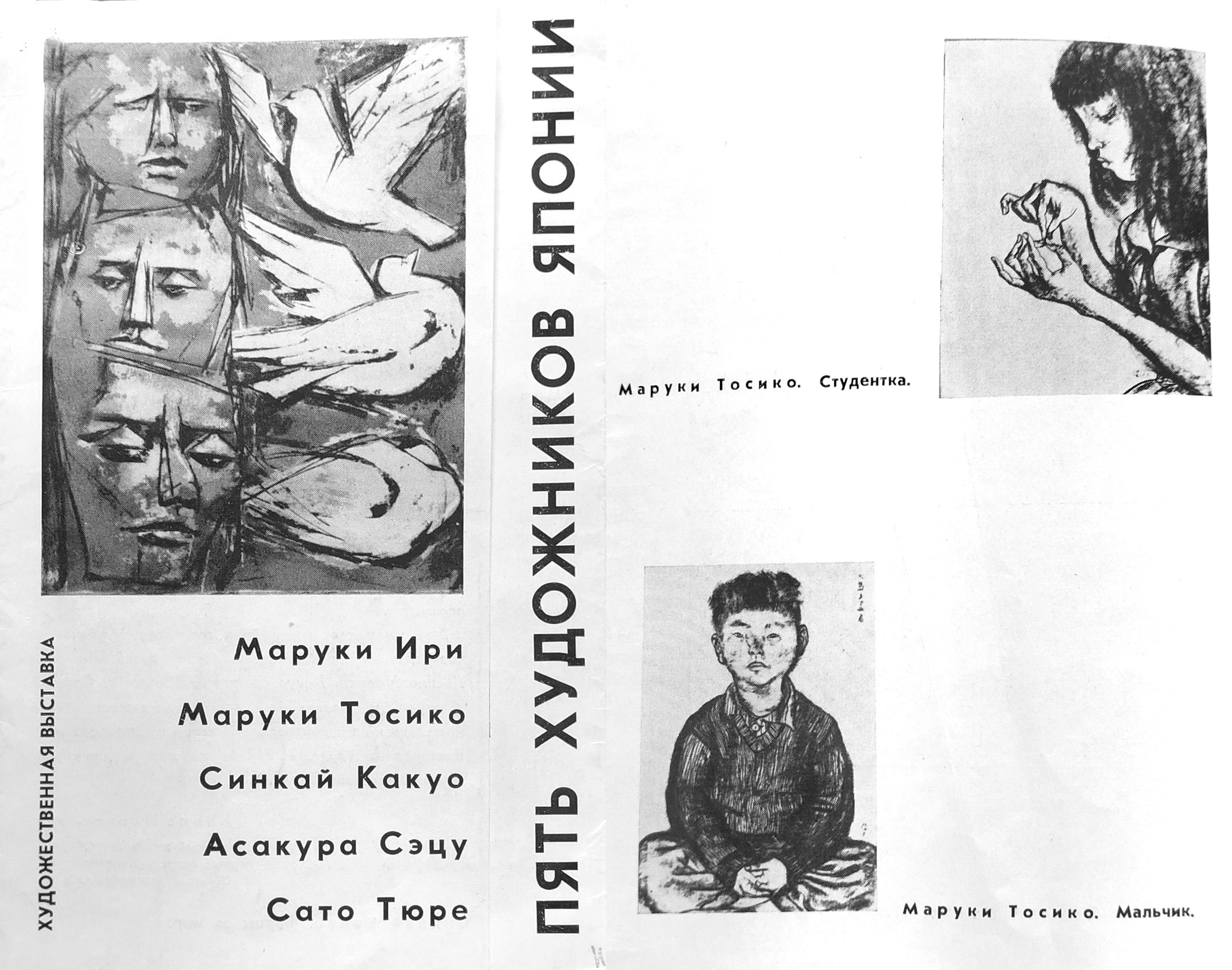

On 21 April 1966, a delegation of artists consisting of the Marukis and Shinkai Kakuo arrived in the USSR at the invitation of the Artists' Union of the USSR for a period of three weeks. During the trip they visited: Moscow, Leningrad, Yerevan, Tbilisi. In Moscow they visited the current exhibitions of A. Gerasimov, Titov, Suslov and young artists of the Artists' Union of the USSR, walked around the territory of Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy and Sokolniki Park. Personal meetings were also held with D. Shmarinov, V. Tsigal and the Aslamazyan sisters. In Georgia, visits were made to Georgian artists, in Armenia the delegation visited the atelier of artist A. O. Grigoryan, and a meeting was held with M. S. Saryan [37]. The opening of the exhibition of five Japanese artists took place at the beginning of May (presumably itinerary: Riga, Kiev, Kharkov, Kuibyshev (presently Samara), Saratov, Bryansk, Kursk, Novosibirsk, Kemerovo [38]), on the 21st of May the Marukis organised a masterclass where they demonstrated their drawing technique. A large number of works were acquired by the State Museum of Oriental Art during this exhibition (9 works by Toshi, 5 works by Iri) [39]. According to the list, Toshi presented 114 works and Iri 81 works [40]. After the artists expressed their desire to stay in the USSR for an additional 12 days to paint a series of works about the Soviet Union, they were given permission and direction to the House of Creativity "Senezh" where they could work together with Soviet artists [41]. The Marukis eventually visited Senezh where meetings with the artists were arranged [42]. In April 1967, an exhibition of five Japanese artists was opened in Kiev (previously in Moscow, Kuibyshev, Kharkov) [Opening of an exhibition of works by four artists 1967, p. 77].

"They brought new works to Moscow. Iri Maruki showed landscapes made in the national technique of "sumi-e" (ink blurring). In his images of trees, flowers, animals there is a unique originality of vision, depth of feelings and thoughts. Toshiko Maruki performed portraits of girls and children. These works are characterised by poetry" [Works by Japanese artists in Moscow 1966, p. 77].

"Toshiko Maruki is the author of the popular painting “May Day Demonstration in Japan”. Her works are characterised by expressiveness and skill. Her heroes are ordinary people, workers and loaders, people exhausted by hard labour. "Peasant, speaking at a rally", "Meeting in Hiroshima", "May Day" — these are the paintings where the theme of the struggle for peace and the struggle against social injustice continues to be the main in the work of the artist" [Kuzina 1966].

In the autumn of 1966, the Marukis visited the Academy of Arts and hoped that the Soviets would purchase their paintings. They also appealed to Soviet organisations to help fund the construction of a peace museum. As a result of this request, the Artists' Union of the USSR and the Soviet Committee for the Defence of Peace allocated three million yen (eight thousand seven hundred and eighty-five rubles) from the peace fund. Part of this money was raised through the purchase of the Marukis' works, fifteen works for the sum of two thousand roubles. It was also decided to provide works from the fund of the Artists' Union of the USSR for subsequent display in the planned Maruki Museum [43]. The total amount of the museum construction reached 25 million yen, and the works provided by the Artists' Union of the USSR, as it follows from the documents, were included in the museum’s exposition [44], but their subsequent whereabouts and fate are unknown [45]. Additionally, in their letters, the Marukis described their financial situation, stating the need for ideological and financial support, as well as selling houses and land and taking out loans of five million yen from the bank to build the museum [46].

"Immediately after the war — the artists said, when the peace movement in Japan was still monolithic and there was not the split that occurred later, the idea of creating a Pantheon for the victims of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima came up. It was to stand on a high mountain, offering a picturesque panorama of the city lying below. The municipality even allocated a plot of land for it. Artists, sculptors, architects from all over the world were to be invited to design and build this monumental structure. In it we expected to place the paintings "The Horrors of Hiroshima" [Kolomiets, 1968, p. 45].

In December 1967, 63 graphic works by Soviet authors were sent to Maruki Toshi as a gift from the Artists' Union of the USSR [47]. Also in 1967 Maruki Iri [48] and Maruki Toshi [49] received the status of honourable foreign members of the Academy of Arts of the USSR (in 1991 the status changed to honourable foreign members of the Russian Academy of Arts).

"We were surprised very much as this election came as a surprise to us. Have we deserved the honour of being elected honorary members? If so, we regard this election as an appreciation of the merits of the Japanese people’s endeavour for peace. Once again, we thank you from the bottom of our hearts for this high honour. At the same time, we feel a great responsibility. Do we have the strength to live up to it? In any case, we will devote our entire lives to it" [Kolomiets, 1968, p. 42].

In November 1967, the Marukis visited Irkutsk and gave 21 works to the museum, including sketches from the Hiroshima Panels, as well as some landscape and genre works [Sketches from the series "Hiroshima" 1967, p. 6].

"Valuable gifts to the Irkutsk Regional Art Museum testify to the huge sympathy and boundless respect of Japanese artists for Siberians, for the entire Soviet people" [Fatyanov 1967].

Conservation of the Marukis' image after 1967. Causes and consequences

The history of visits and references to the Marukis suddenly ceases after 1967-1968, their names and articles almost disappear from the pages of magazines and newspapers. In the fonds of the Union of Soviet Societies of Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries beyond this time mark there are practically no documents mentioning the artists once beloved by the Soviet Union [50]. There may be several reasons for this attitude towards the artists; let us try to turn to a few indirect facts that point to the breakdown of ties and the preservation of information regarding the Marukis and their works.

In 1964, the Marukis resigned from the Communist Party of Japan (CPJ), which they had joined immediately after the end of the war. In the Soviet press this was reflected in a series of statements made by various Japanese cultural figures who were dissatisfied with the current state of affairs and criticised the party’s political course. They argued the need to renew the forces aimed at the positions of proletarian internationalism, as well as to stop the party ignoring the specifics of mass movements [Statement by Japanese cultural figures 1964, p. 5]. Additionally, the anti-Soviet position of the CPJ was mentioned, but what is most important in the context of the Marukis and their views is the split over the views on the concept of peace and the prohibition on the use of nuclear weapons [Maruki 1964, p. 5]. Other sources presented the Marukis' exclusion in a slightly different way, for example, the transcript of a lecture by art historian A. Kolomiets states that the Marukis broke with the CPJ because of its anti-Soviet attitude, which is a distortion, since the set of reasons for the Marukis' withdrawal from the party was broader [51]. Only one archival document shows the Marukis' expulsion from the CPJ, the reason for which was explained by criticism of the party leadership [52].

After 1964, as can be seen, the Marukis' exhibitions did not stop, artists' texts appeared, and the Soviets even allocated a large sum of money for the construction of their museum, seeing it as a platform for the presentation of Soviet art. But if we will pay attention to the references to the Marukis in the books of the 1970s and 1980s, they are insignificant and short, no more than two or three sentences, and their content does not provide any new information different from things what was published in the 1950s and 1960s [53]. The total number of references to the Marukis exceeds that of any other artist from Japan; they remained the face of modern Japanese art in USSR throughout the period from the early 1950s to the late 1980s. The only problem is that the Marukis' work, as well as the image of the artists themselves, has been conserved in the Soviet version of Japanese art history. There was no discussion of the artists' work beyond the Hiroshima Panels (ten out of fifteen) and some graphics that were kept in the collections of Soviet museums. In addition, the maintenance of their status as protagonists of Japanese art was also based primarily on the absence of new names, the lack of research in the field of contemporary Japanese art, and the general freezing of this subject at the level of the 1950s and 1960s.

However, this story would be incomplete were it not for another reason, which apparently stopped their frequent visits to the Soviet Union. In 1970, the Marukis made their first trip to the United States, where they showed their work and met the American people. The trip was successful, including the development of the artists' creative intentions, but this trip apparently closed the opportunity of the Marukis' visits and publications in the USSR, but did not exclude their participation in international events in other socialist republics.

Reviews of two events — the Biennale of Illustration in Bratislava and the Triennale of Realist Art in Sofia — are the only ones that allow us to trace some trajectory of the Marukis' work in the Soviet sources for the period of the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1967, Maruki Iri received an encouragement diploma of BIB-67 for his illustrations for the book "Dumpy, the Shorty Who Rolled into Mouse Paradise" [Petrov 1968, pp. 56-57]. In 1971 Maruki Iri and Toshi received the Golden Apple award for their illustrations for the book "Japanese Legends" [Minutes of the Jury Meeting of the International Biennale of Illustration Bratislava 1972, p. 56]. Regarding this Biennale, its reviewer, V. Rakitin wrote: "In the works of artists more openly orientated on the plasticity of European painting of the middle of our century — and among them were bright fantastic illustrations by Iri and Toshi Maruki for "Japanese Legends" — there is no such purity and integrity" [Rakitin 1972, p. 77].

In parallel, the magazine “Tvorchestvo” (“Creativity”) published reviews of the Sofia Triennale. In the first publication by E. Singer from 1980 mentioned only the Maruki’s participation [Singer 1980, p. 14], in 1982 the reports of the international jury prize winners were mentioned [Singer 1982, p. 23], among them the Marukis, and in 1985 the only mention of the Marukis' new works was made:

"Huge, full-wall, multi-part panels executed in ink on homemade paper ("…. Atomic Reactor, Sandrizuka, 1982", "Auschwitz", "Hell") were striking not only for their size, the number of depicted characters, but also for the truly epic scope of dynamic compositions, where in a single stream moving masses of protesting workers, defending their rights — small figures, over which are hovering the monsters of the Japanese militaristic spirit, with portraits of figures of the present and the recent past; bodies plummeting downwards, cutting through the pitch blackness ("Inferno". 1985). For all the "apocalyptic" abstraction, these compositions have, however, an open political programme" [Singer 1985, p. 18].

The last mention, by D. Dimitrov, indicated another participation of the Marukis at the exhibition in Sofia: "a huge anti-war panel by Japanese artists Iri and Toshi Maruki, and pictures painted on the canvas of a tourist tent". [Dimitrov 1988, p. 1]. There were also brief mentions of the Hiroshima Panels, in the magazine "Iskusstvo" ("Art") from 1982, which mentioned the exhibition in Osaka [Art in the fight against nuclear threat 1982, p. 74], and in the material of the magazine "Detskaya Literatura" ("Children’s Literature"), which simply used one illustration by Maruki Toshi to the book "Hare’s hut, a Russian folk tale" [Children’s Book Covers and Illustrations 1986, p. 64].

It was impossible to see new works by the Marukis, but older ones, from collections, could be caught at some group exhibitions. In 1985 there was an exhibition called "With the Thought of Mothers", based on the collection of writer Savva Dangulov. An exhibition of 100 works by various artists, including Maruki Toshi, was shown at the House of Friendship with Peoples of Foreign Countries in Moscow [With the thought of mothers, 1983]. In 1986, the exhibition "Oriental Art in the Struggle for Peace and Humanism" also showed the Marukis' works in the collection of the Oriental Museum, but there was no development in the descriptive part of the catalogue, just another repetition of the same information about the Hiroshima Panels [Oriental Art in the Struggle for Peace and Humanism, 1986]. The following works were shown: "Girl with Cranes", "Girl Illuminated by Fire", "Mount Fuji in the Clouds", "Camellia".

In documentary terms, the only reference found is from 1988. In the course of correspondence with the management of the Centre for International Friendly Exchanges, it turns out that the Soviet side refused to hold the Marukis' exhibition with the following wording: "…the Soviet side also refuses to hold an exhibition of works by famous Japanese anti-war artists, the Maruki spouses, who were expelled from the CPJ in their time" [54]. Unfortunately, the reason for this cancellation is not specified in the document.

It is also interesting to note that during the construction of the Marukis' image in the USSR, for some reason, not once, neither in the documents, nor in numerous interviews, the pre-war visit of Maruki Toshi was mentioned, the first visit was considered only in 1953. Also, apparently due to financial non-disclosure, the financial contribution of the Soviet side to the museum was never mentioned, it was claimed that it was the Marukis who personally collected the necessary sum of money [Kolomiets 1967, p. 4]. Although usually such steps, including the concept of the USSR’s participation in peace building, were voiced and used as official propaganda.

The history of the cooling of interest in the Marukis shows the following trend: the artists were not expelled from the Academy of Arts, nor were they completely erased from the books, but their position was canned within the framework of those works that had already been shown in the USSR and were familiar to Soviet audiences. Conceptually, they remained within the general agenda of the struggle for peace, but without being extended to other tragedies, whose artistic reflection the artists continued to pursue. All subsequent work on American prisoners of war, the Nanjing Massacre and concentration camps fell off the Soviet art historical agenda and were never recovered. The absence of the Marukis' publications, mentions, or letters in archival documents, compared to the abundance of material from the 1960s, raises questions. There is no unambiguous answer to this question, it remains only to put forward a set of assumptions, which includes both a divergence of views on the use of nuclear weapons and the loss of certain ties and significance in the eyes of the Soviet Union, and the 1970 trip to the United States. Among the general trends, we can note the fading of the historiographical component in relation to Japanese art in the 1970s and 1980s, but these are additional factors that have a greater impact on the number of publications about the Marukis than on the absence of their trips to the USSR after 1967.

The image of the Marukis in Soviet art history: 1950s-1980s

The first publications about the Marukis appeared in early 1953, the texts of this decade retell the story of the creation of the Hiroshima Panels in detail [Karten 1955, p. 4], mentioning the trip to Hiroshima, the work on the panel and the exhibitions organised by the artists. The articles followed the same vector of reasoning — discussion of the use of nuclear weapons, strengthening of the struggle for peace, US responsibility for the bombing. The only thing is that there were exceptions, where, for example, sometimes the authors were confused: in some situations, the artists immediately went to Hiroshima [Voronova 1959, p. 4], in others Iri did it first [Guests from Distant Japan 1956, p. 4], the same can be observed in the difference about the dead relatives of the artist (father [Kibrik 1959, p. 3] / father, uncle and two nieces [Guests from Distant Japan 1956, p. 4]). In addition to the image of sacrifice and heroic deed, which reflected the realities of the occupation, there were stories about the difficult display of artists' works, the lack of resources, such as the problem of availability of gold paint for the panel "Fire" [Svetlova 1959, p. 15], as well as the opposition of the Marukis to abstract painting.

Most of the panels were evaluated by the authors as a worthy contribution to the struggle for peace and a successful combination of Japanese and European artistic traditions.

"This is how the 'mixed style' emerged. Its manifestations are very diverse. One of them is the combination of ink painting with the techniques of European watercolour or graphics. Such are "Volcano Asama" and other landscapes of Iri Maruki" [Nikolaeva 1968, p. 93].

Art historian N. Kanevskaya, saw in the Hiroshima Panels the general accessibility of artistic language and appeal to topical issues, while postulating that "the final transition from medieval art to modern forms was made, a new world of images and new possibilities of ideological and emotional enrichment of painting were opened" [Kanevskaya 1978, p. 15].

Similarly, but much broader in its explanations, the series of panels was reviewed by V. Brodsky, who wrote that the Hiroshima Panels was a great asset in the field of national tradition and the inner essence of European painting, and it was thanks to the traditions of realist art that the work received the pathos of protest and struggle. At the same time V. Brodsky, the only Soviet author who was disappointed with the panel "Petition", considering that the work was impoverished, and the symbolic attributes (doves, sakura branches) further increased the gap between the true meaning and the viewer, making the work inexpressive [Brodsky 1961, p. 177]. V. Brodsky had less significant compositional claims to the panels "Ghosts" and "Fire". The author wrote the following about "Atomic Desert": "The abstraction of the depicted figures, the artificiality of the whole composition abstract the picture created by the artists from the real event, incomparably more tragic and terrible, and take the viewer into the realm of sometimes quite banal symbolic representations and associations" [Brodsky 1961, p. 176]. The same is found in the text of D. Shmarinov, a close friend of the Marukis: "A number of panels are hindered by a shade of abstract symbolism — this applies, in particular, to such an interesting in composition panel as 'Rainbow'" [Shmarinov 1957, p. 261].

Naturalism, the presence of nudity and dead bodies was not mentioned in a specific way, only in one of the texts the topic was touched upon as follows: "It may be that artists, when creating paintings dedicated to human misfortune, sometimes cross the boundaries of art. Some fragments of the panels are naturalistic and arouse disgust rather than pity. But even with this technique, the Marukis achieve their goal. Contemplation of horror and ugliness causes the desire that it should not be repeated" [Galerkina 1964, p. 397].

Although a detailed description of what is happening on the panel was used in the catalogue texts and explications:

"…A small child pushes away the hands of a man trying to pull him out and burns in his mother’s arms, crushed by a pile of bodies and ruins. People fall burnt, some with shattered heads, some with shards of glass in their stomachs. And here, the arms are torn off and only the legs continue to move…" [A series of panels by International Peace Prize-winning Japanese artists Iri Maruki and Toshiko Maruki 1959]

The case of the Marukis also demonstrates the problem of art historical optics in the Soviet period, which, because of its closeness to the ideological regime, allowed for the elimination of some obvious artistic properties of the depicted. This was especially true of the surrealistic qualities of their works, which was correctly noted by art historian P. Muratov in his reflections on the exhibition’s arrival in Novosibirsk: "Little was written about the exhibition, avoiding the characterisation of the signs of surrealism alien to socialist realism, but it was deeply embedded in the consciousness of those who saw it" [Muratov 2012, p. 181].

"The world-famous anti-war panels were difficult to enter the exhibition space of the USSR. From the point of view of the notions of "correct" and therefore good, more or less acceptable was only the last panel "Collection of Signatures"…The other nine had clear signs of surrealism" [Muratov 2012, pp. 157-158].

Obviously, the status of the artists and their importance in demonstrating the anti-nuclear and anti-American message was above some of the surrealistic details of their work, so this was deliberately overlooked, and in the texts the role of surrealism was devalued and contrasted with the humanistic characteristics of art.

"In the early period of her creative activity (which coincided with the war), she, like many young artists of her time, became fascinated by surrealism. Toshiko in those years saw it as a peculiar form of protest against militarism, slushy naturalistic battle paintings, glorifying the heroics of war… Surrealism in the Japanese post-war art rose to the service of the most reactionary forces, and Toshiko moved away from it completely. The spirit of cruelty and pathological instincts of the surrealists was extremely alien and hostile to the artist, whose entire work is inspired by the spirit of humanism and faith in the light human beginning" [Kolomiets 1968, p. 44].

"It must be said that many surrealist artists in Japan tried to depict the tragedy of Hiroshima. But the people didn’t understand them. So they needed a different artistic medium, one that ordinary people could understand. Maruki and Akamatsu break with surrealism" [Guests from distant Japan 1956, p. 4].

For this reason, the scale of the works was also endeavoured to be compared to the "greats" in order to give them the proper significance of the level of the works and their creators.

"The Marukis' panels reminds us in some ways of the famous illustrations to Dante Alighieri’s Inferno. But no imagination of the poet and his illustrators can compare with what happened on earth on a sunny August day in 1945 due to the fault of the American imperialists" [Fonyakov 1960, p. 4].

"In this sense, the “Hiroshima” series brings to mind Michelangelo’s 'Last Judgement'. It is impossible, it seems to me, to have a more honourable connection, a greater and nobler example, since "The Last Judgment" is one of the grandest works of world art" [Kibrick 1959, p. 3].

"They learnt much for themselves in the work of such giants as Michelangelo and Goya…" [Shmarinov 1957, p. 261].

"In this sense, the series of scrolls "Hiroshima" can be compared with the Chinese artist Jiang Zhaohe’s painting "Refugees" …. If Jiang Zhaohe gives a variety and deep psychological characteristics, the Marukis operate only plastic expressiveness of the image of man" [Brodsky 1961, p. 177].

Mention of the Marukis in the press and books was as abundant in its quantity as their frequent visits until 1968. There was regular coverage of the artists' formation and the creation of the series of "Hiroshima Panels", but the information was repetitive. On the positive side, there was enough room for numerous reproductions that appeared not only in the press, but also on postcards ("Through the Eyes of Artists", 1964), in slide film ("Contemporary Japanese Art", 1962) and in albums and collections of posters ("Friends of October and Peace", 1967; "Artists of the World in the Struggle for Peace", 1963; "Standing Together for Peace on Earth", 1962). However, there was no new material or conceptual development of reviews of the Marukis' work, even the last actual publication for the period of the late 1960s, authored by A. Kolomiets, was devoted to their opened museum, where only one new work was mentioned in passing [Kolomiets 1968, p. 4]. In addition, there was a certain emphasis only on the realistic qualities of the works, while any other artistic experiments and techniques were kept silent because they did not correspond to the aesthetic categories of social realism. For this reason, we have to speak of the conservation of the image and analyses of the Marukis' work in texts after the second half of the 1960s, the absence of new knowledge and the deliberate silencing of the artists' activities after this time mark.

The Marukis' last visit and exhibitions in the post-Soviet period

The Marukis' first and last visit to Russia since 1967 was in 1990, when the couple travelled to Vladivostok for an exhibition. According to the recollections of Alexander Gorodny, director of the Artetage Museum, who accompanied the artists around the city, it was an impressive event, as the city at that time continued to have a closed status (until January 1992), so the appearance of foreigners there aroused curiosity and interest in their works. The artists' exhibition was held at the Primorsky State Art Gallery, and Leonid Anisimov, director of the Vladivostok Chamber Theatre, helped to invite the artists. The artists presented two drawings to the gallery from their Paris series of nude sketches of the mid-1980s [Levdanskaya 2023, p. 234]. It is also known that at the time of their arrival Maruki Iri’s 89th birthday was celebrated, a concert and feast were held in his honour [55]. Unfortunately, the exhibition was not mentioned in the major art magazines, the Marukis' figure was lost among other events and names of the time.

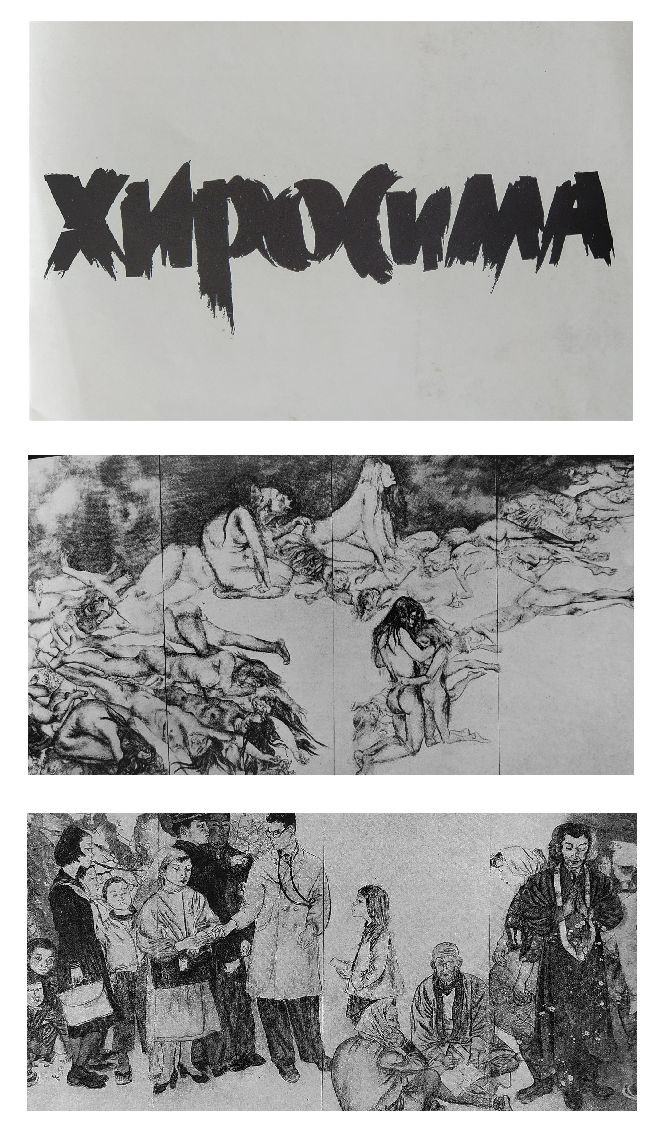

The Marukis' first exhibition in Russia took place in April 1999, at the Yuri Mirakov Studio-Gallery in Moscow. More than forty graphic works of 1950-1960s by the Marukis were shown there [56]. The publication of the book "Hiroshima" by Maruki Toshi, with illustrations by Iri, the first and only one that was translated and published in Russian in 2011 [Maruki 2011]. The publication dealt with the tragedy in Hiroshima, much in the spirit of the panel series, but with a focus on a juvenile audience. Unfortunately, no other books or albums authored by the artists have been published, which, however, also applies to scholarly publications. The works presented to the Irkutsk Art Museum in 1967 were shown again in 2015 at the exhibition "Fragility of the World". The exhibition was timed to the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

"Toshiko Maruki Speaks": texts by the Japanese artist in Soviet magazines and newspapers

In addition to interviews with artists, texts, mostly by Maruki Toshi, appeared repeatedly in magazines and newspapers throughout the 1950s and mid-1960s. Such articles most often dealt with two topics: impressions of visits to the Soviet Union and the state of contemporary art in Japan.

The first such article was "So Many Beautiful Things!" [57] published in 1953. In this text, Maruki Toshi described her impressions of her first trip to the USSR after the war, where she mostly described her itinerary, while admiring the living conditions in the Soviet Union, how different they were from the harsh living of artists in Japan [Akamatsu 1953, p. 45-47]. She was also delighted that artists in the USSR live well and have their own studios:

"I met with artists from Yerevan and Leningrad. I learnt that they all dress well, have studios, live well…I know that Soviet artists, who have the experience of the great revolution and the Great Patriotic War, will understand the unimaginably difficult conditions under which Japanese painters continue their work. And I believe that the rich and meaningful life lived by Soviet artists will also come to us…Long live the Soviet Union — the dawn of civilisation for all mankind!" [Akamatsu 1953, p. 46]

Five years later, the text "Against the Atomic Bomb", co-authored by the Marukis, appeared in the newspaper "Sovetskaya Kultura" ("Soviet Culture"), describing impressions of artistic life in Japan. The artists' position was presented as follows: many galleries and department stores were full of Western art and abstractionism, but the artists themselves believed that painting could also reflect the theme of the struggle for national independence. In the same text, for the first time for a Soviet audience, they announced a plan to build their museum in Hiroshima, where they planned to collect works by Japanese, Soviet, and Chinese artists opposed to the war [Maruki 1958, p. 4]. In the publication "Pictures of Japanese Life" of the same year, the artist presented a short essay with many illustrations showing the life of fishermen, workers, women and children in post-war Japan [Maruki 1958, pp. 26-28].

In 1959, the text "Hello, dear country!", written by Maruki Toshi, recounted the experience of opening the first large-scale exhibition of artists, as well as a visit to Senezh Lake. The text included several illustrations showing the national landscapes and people, including a sketch of visitors to the exhibition at the Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure. Maruki again spoke about the goodness of the existence of Soviet artists: "In Japan, with the exception of a few, artists are very poor and are forced to take up any trade instead of creative work to somehow make ends meet…Here artists can rest in peace, gain strength and inspiration for new creativity. And at the same time spend time together with their families!" [Maruki 1959, pp. 44-45]

In "The Light and Shadows of the Japanese palette," a text from 1966, Maruki Toshi continued her observations on the state of contemporary art in Japan. She once again voiced her opinion about Japanese artists copying Western works and contrasted this with the paintings of Soviet artists, who, according to the artist, had a different audience capable of "thoughtfully looking at their work". The author was also offended when Soviet artists did not receive awards at the International Print Biennale in Japan, as all the prizes went to abstractionists. At the same time, she mentioned that when ancient Russian art and Venus of Milos were shown in Japanese museums, the queue for these exhibitions was equal. Maruki Toshi held more progressive views regarding the position of Japanese women artists, stating that in Japan there are feudal prejudices against women artists, and they very often have to fight against the male monopoly in art [Maruki 1966, p. 4].

"Hiroshima is a turning point in my art", another text from Maruki Toshi that appeared in "Zhenshchiny mira" (“Women of the World”) magazine in 1967. The article was entirely devoted to the artist’s views on art, her personal growth and call for the inadmissibility of wars and the use of nuclear weapons.

"I feel ashamed and afraid when people praise what I have created. I have not yet reached the level of art that I would like. I am no more than an apprentice in my craft. The longer I live and the more I think about it, the more I am convinced of this" [Maruki 1967, p. 50].

In the text "Toshiko Maruki Speaks" the artist again referred to her experience of visiting the USSR: she mentioned visits to the Piskarevskoye cemetery in Leningrad, where she felt it was important to note the role of memorial memory, as well as her trips to Moscow and Samarkand.

"In Moscow, in the Tretyakov Gallery, looking at the elegance of the execution of Old Russian icons, I felt happy again. Repin and Vrubel, Levitan and Shishkin have forever chained me to their works. As if bathed in the rays of the dawn dazzlingly bright canvases of Saryan. The works of Konchalovsky, who is well known in Japan, seem to open the veil. At the exhibition of Pavel Kuznetsov I thought: the works of this fine artist are beautiful" [Maruki 1966, p. 12].

"Falling towers and minarets, a dazzling wealth of human imagination, creations rare and unique. It takes a generation’s long labour to create them. I was shocked by the masterpieces of art of Central Asia, struck by the amazingly careful attitude of the Uzbek people to their culture" [Maruki 1966, p. 12].

Maruki Toshi also spoke about the importance of not losing oneself in one’s art and fighting against monotony, about the need to find a painting that is both modern and national, in this respect she was oriented towards V. A. Favorsky, whose exhibition she visited during her 1966 trip.

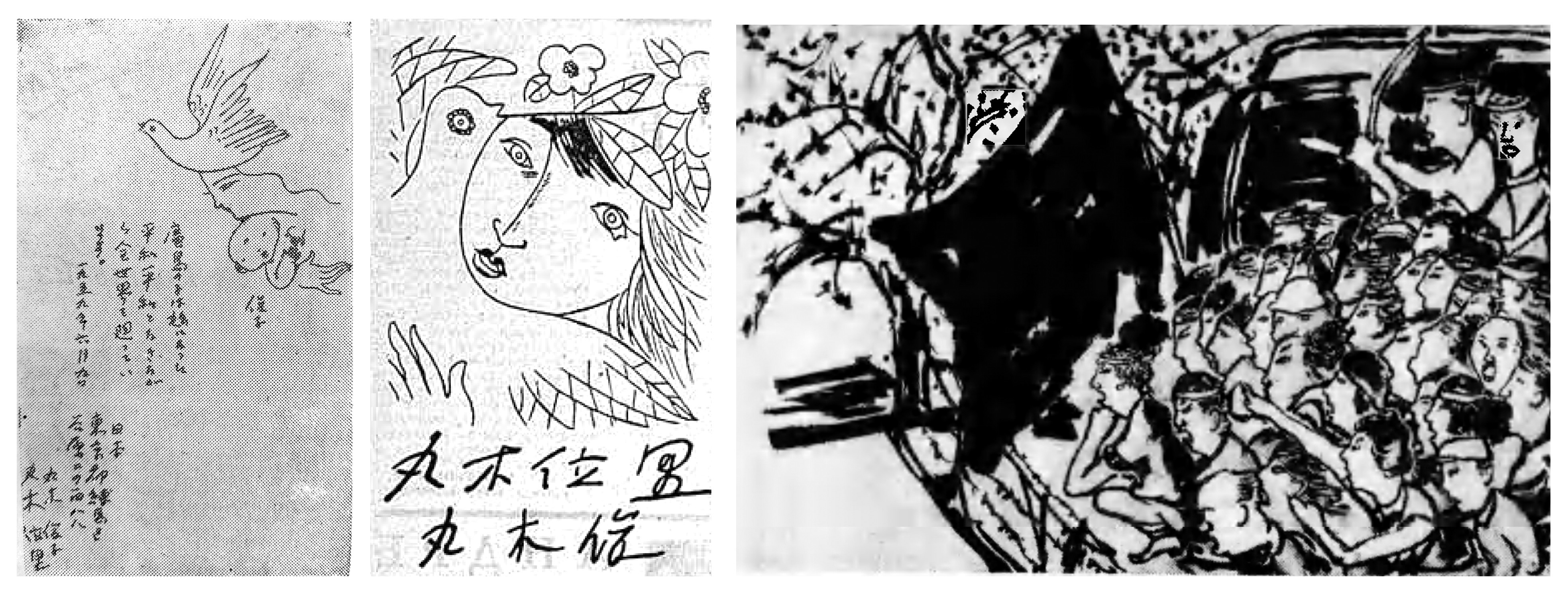

It should be noted that some drawings were specially prepared by artists for Soviet issues of magazines and newspapers. Maruki Iri made a drawing depicting a people’s rally in Japan for the "Literaturnaya Gazeta" ("Literature Newspaper)" in the article "Japan fights for peace" [Dan 1956, p. 4]. A separate drawing by Maruki Toshi, presented to the magazine "Far East", was published on its pages with the caption "The child of Hiroshima has become a dove. It soars over the world with the cry: "Peace! Peace!" [Chukanov 1960, p. 191]. In 1968, a small letter from the Marukis was published in "Soviet Culture" newspaper about the memorial events in the museum dedicated to the victims of Hiroshima, with a drawing attached to it [Salnikov 1968, p. 4].

It can be seen that texts of Maruki Toshi mainly demonstrated her impressions of her visits to Moscow, which seem somewhat one-sided and overly enthusiastic in the present time, but such were the realities of the visiting life of foreigners in the Soviet Union. More important is the information about the artist’s orientations, as well as her own thoughts on the state of contemporary Japanese art. Of great value are the texts, which are illustratively arranged, allowing us to look at how Japanese artists saw the local context and captured it.

Evidence of the Marukis in travelling notes and memoirs

In the memoirs of some cultural figures and diplomats, one can also find mention of meetings with the Marukis. In 1964, I. Fomin, a member of the Union of Soviet Societies of Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries special tour group, had a meeting with artists, including the Marukis, at the Soviet embassy in Tokyo. During this conversation, the Japanese side was interested in the work of Soviet artists, their attitude to abstraction, and I. Fomin noted that the Japanese had a good knowledge of Russian and Soviet painting [58]. The manuscript of an unpublished book "Meetings with Japanese Art" by art historian O. I. Galerkina [59], planned for 1965-1966, also mentioned a meeting with the Marukis during the author’s trip to Japan [60]. Writer V. Efimenko mentioned his meeting with the artists at a reception in honour of the 49th anniversary of the Great October Revolution (1966), noting that he met them and some other guests during their visit to Khabarovsk [Efimenko 1967, pp. 38-39]. In the spring of 1968, A. D. Fatyanov, director of the Irkutsk Art Museum, travelled to Japan, where he visited the Maruki Gallery, saw the exhibition and the works of Maruki Suma (1875-1956), Iri’s mother. At the time of Fatyanov’s stay in Japan, the Marukis were working on the panel "Floating Lanterns". He also met their niece, she was finishing her studies in Moscow at that time and was engaged in performing Russian folk songs in Japan, Fatyanov noted that she had a good knowledge of the Russian language. At parting he was given a drawing of Maruki Iri with the image of a butane flower, which later entered the collection of the museum together with other works [Fatyanov 1974, p. 126-129]. It is known that from the same trip the director of the museum brought back more than twenty drawings of Japanese children as a gift [Alexandrova 1970, p. 142].

The Marukis in the sculpture of Soviet artists

It is worth noting that the Marukis were immortalised in sculpture by two Soviet sculptors. First of all, by Vladimir Tsigal, who knew and communicated with the artists, resulting in three sculptural works: "Portrait of the Japanese Artist" (Zelenogorsk Museum and Exhibition Centre), "Portrait of Iri Maruki" (Vyatka Art Museum named after V. M. and A. M. Vasnetsov), and a paired, most expressive, portrait from 1960 (Ivanovo Regional Art Museum). In 1966 Khachatur Iskandaryan also created a sculptural bust of Maruki Iri (National Museum of the Republic of Sakha) [61].

The Marukis' works in the museums and private collections in Russia

Russia has the largest number of the Marukis' works outside Japan. Particularly favourable is the fact that the works found their way not only to Moscow museums, but also remained in the collections of various regional institutions. However, due to the centralisation of artistic life in Moscow, most of the works are in the State Museum of Oriental Art (76), as it was there that Marukis' exhibitions were most often held and purchases made, either through the USSR Ministry of Culture or the Artists' Union of the USSR. Among regional institutions, the Irkutsk Regional Art Museum named after V. P. Sukachev [62] (24) takes the lead in terms of the number of the Marukis' works, since this venue also, as mentioned above, has a long history of relations with Japanese artists. In other museums the Marukis' works are represented in small numbers: Samara Regional Art Museum[63] (9), A. N. Radishchev Saratov State Art Museum [64] (3), Primorsky State Art Gallery (2), G. A. Travnikov Kurgan Regional Art Museum [65] (1), State Hermitage Museum [66] (1). Also, several reproductions of the panel "Hiroshima" are kept in the State Museum of History of St. Petersburg (7).

Among private collections, Savva Dangulov is known to have works by Japanese artists, including Maruki Toshi [67] (5). In the mid-1980s, the writer donated the collection "With the Thought of Mothers" to the Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya Central Children’s Library in Armavir, where the art gallery is now located. There were also discovered several works as part of two private collections, a total of five works by the artists, graphic works by Iri (3) and Toshi (2), but in order to respect the privacy of the owners of these works, details about these works are not given in this text.

The Return of the Marukis

The importance of the Marukis' contribution to the world’s post-war art cannot be overestimated; their simultaneously artistic and documentary statement on the Hiroshima atomic bombings attracted the attention of the whole world, including the USSR. Their close relationship and mutual interest in each other was dictated by the strength of the political statement of their works, as well as the artists' desire to spread the knowledge of the tragedy.

The frequent Marukis' shows that saturated the event space of the 1950s and 1960s were beneficial because of their anti-war stance and humanist aspirations, which fitted into the Soviet programme of "struggle for peace", and because of the anti-American overtones, as the artists' status and the message of their work were ideologically advantageous. The trajectory of their artistic development, through numerous publications and shows, was framed by Soviet art history with these political needs in mind, ignoring some of the "formalist" qualities of their work, thus as if allowing the viewer to see more of what was allowed. However, due to the political transformations of the communist movement in Japan, the Marukis' changing personal views and the trip they made to the United States in 1970, the relationship between the artists and the Soviet organisations had come to an end. This move did not lead to a complete ban or exclusion of the artists from the pantheon of contemporary Japanese artists, but to the preservation of knowledge about the Marukis and their work, at the level of discourse that had been articulated in the 1950s and 1960s.

Unfortunately, such processes had a negative impact on further coverage of the Marukis' work in the Soviet Union, completely excluding any other projects by artists dedicated to other world tragedies, from Nanjing to Auschwitz. Despite this, in the midst of such relationships woven over the two decades of their active visits, there was room to communicate and establish friendships with Soviet artists, to enrich the collections of Soviet museums through the purchase of Marukis' works and their gifts. Not to mention the assistance of Japanese artists in organising Soviet exhibitions in Japan.

The outcome of this story demonstrates how complex the space of cultural relations can be, even when Japanese artists held similar ideological views and had nothing to do but show their work and spread their peace message. The Marukis are undoubtedly very important artists of their time and it is particularly regrettable to note how a process of conservation of knowledge has taken place, creating a hollowness and alienation of artists for many years to come. It is sincerely hoped that the publication of this text will contribute, at least to some extent, to the return of their names and a rethinking of what happened, as well as signalling goodwill to researchers around the world who are dealing with the Marukis' legacy.

List of exhibitions and the Marukis' visits to the USSR/Russia:

April 1937 — March 1938 — Akamatsu Toshiko worked as a governess in Moscow.

January — June 1941 — Akamatsu Toshiko worked as a governess in Moscow.

Summer 1953 — Arrival of Maruki Toshi as part of a women’s delegation [Moscow, Leningrad, Armenia, Georgia].

November 1956 — The Marukis' visit and exhibition in the halls of the Moscow Regional Union of Artists (Moscow).

Autumn-Winter 1957 — The Marukis' visit to the USSR to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Academy of Arts.

1959-1960 — “Hiroshima” exhibition in the USSR (Moscow [Exhibition Pavilion in the Gorky Central Park of Culture and Recreation, June 1959], Leningrad [Mikhailovsky Palace, 1959], Stalinsk [October-December 1959], Novosibirsk [February 1960]). The Marukis' presence is known only at the Moscow exhibition.

May-July 1962 — Participation in the group exhibition "Modern Painting of Japan" [The State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow].

December 1964 — Arrival of Maruki Toshi as a member of the women’s delegation.

January 1965 — Arrival of Maruki Toshi to the USSR (At the invitation of the Union of Soviet Societies of Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries)

1966-1967 — Exhibition of Five Artists (Moscow [May-June 1966], Saratov [1-30 December 1966], Kiev [April 1967], etc.).

Autumn 1966 — The Marukis' visit to the Academy of Arts.

November 1967 — The Marukis' visit to Irkutsk (Coming right after from Ulaanbaatar, Mongolian People’s Republic [6 October — 8 November]).

Early 1968 — The Marukis' exhibition in the Irkutsk Regional Art Museum.

Spring 1985 — Group exhibition "With the Thought of Mothers" (House of Friendship with Peoples of Foreign Countries, Moscow). Based on the collection of Savva Dangulov, without the Maruki’s participation.

February 1986 – Group exhibition "Eastern Art in the Struggle for Peace and Humanism" (The State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow). Based on the museum’s collection, without the Maruki’s participation.

June 1990 — The Marukis' exhibition and visit to Vladivostok (Primorsky Art Gallery).

April 1999 — The Marukis' exhibition in the studio-gallery "Yuri Mirakov" (Moscow).

August 2015 — Exhibition "Fragility of the World" (Irkutsk).

Known participation of the Marukis in exhibitions in Sofia and Bratislava based on found sources:

1967 — BIB-67 (Bratislava, Czechoslovakia).

1971 — BIB-71 (Bratislava, Czechoslovakia).

1973 — BIB-73 (Bratislava, Czechoslovakia).

1979 — Triennale of Realistic Painting (Sofia, Bulgaria).

1982 — Triennale of Realistic Painting (Sofia, Bulgaria).

1985 — Triennale of Realistic Painting (Sofia, Bulgaria).

1988 — Triennale of Realistic Painting (Sofia, Bulgaria).

References

- Aleksandrova O. Direktor muzeya [Museum director]. Sibirskiye ogni [Siberian Lights]. 1970. No 8. p. 142. (In Russian)

- Alpatov V. Yaponiya. Spravochnik [Japan. Handbook]. Moscow: Respublika, 1992. p. 271. (In Russian)

- Bunin S., Verbitskiy S., L. Grisheleva. Yaponiya nashikh dney [Japan of Our Days]. Moscow: Nauka, 1983. Pp. 236-237. (In Russian)

- Brodsky V. Seriya svitkov “Khirosima” Iri i Tosiko Maruki [“Hiroshima” Iri and Toshiko Maruki Scroll Series]. Sovremennoye izobrazitel’noye iskusstvo kapitalisticheskikh stran [Modern Fine Art of Capitalist Countries]. Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik, 1961. Pp. 171-178. (In Russian)

- B’yenale illyustratsii Bratislava. Statut [Biennale of Illustration in Bratislava. Statute]. Bratislava: Slovenskaya narodnaya galereya, 1973. (In several languages)

- Cheboksarova N. N. Narody Vostochnoy Azii [Peoples of East Asia]. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka. 1965. p. 919. (In Russian)

- Chukanov M. Risunok yaponskoy khudozhnitsy [A Drawing by a Japanese Artist]. Dal’niy Vostok [Far East]. 1960. No 5. p. 191. (In Russian)

- Dan T. Yaponiya boretsya za mir [Japan Fights for Peace]. Literaturnaya gazeta [Literary newspaper]. 1956. No 10. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Dashkevich Yu. Druz’ya Oktyabrya i mira [Friends of October and World]. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya literatura, 1967. Illustration № 11. (In Russian)

- Dimitrov D. VI Mezhdunarodnaya triyennale realisticheskoy zhivopisi v Sofii [VI International Triennale of Realistic Painting in Sofia]. Tvorchestvo [Creativity]. 1988. No 11. p. 1. (In Russian)

- Efimenko V. Ot Khabarovska do Niigaty [From Khabarovsk to Niigata. Travel Notes]. Putevyye zametki. Khabarovsk: Book Publishing House, 1967. Pp. 231-232. (In Russian)

- Etyudy iz serii “Khirosima” [Sketches from the “Hiroshima” Series]. Pravda. 1967. No 336. p. 6. (In Russian)

- Fat’yanov A. Broshyura k vystavke risunkov yaponskikh khudozhnikov Iri i Tosiko Maruki [Brochure for the Exhibition of Drawings by Japanese Artists Iri and Toshiko Maruki]. Irkutsk: East-Siberian Pravda Publishing House. 1968. (In Russian)

- Fat’yanov A. Zagadka staroy kartiny [The Mystery of the Old Painting]. Irkutsk: East.-Siberian. book publishing house 1974. Pp. 126-129. (In Russian)

- Fonyakov I. Pomni ob etom! Vystavka “Khirosima” v Novosibirske [Remember That! “Hiroshima” Exhibition in Novosibirsk]. Sovetskaya Sibir’ [Soviet Siberia]. 1960. 14 Feb. No 38. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Galerkina O. Iskusstvo Yaponii [Art of Japan] // Istoriya iskusstva zarubezhnykh stran [History of Art of Foreign Countries]. Moscow: Izd-vo Akad. Khudozhestv SSSR, 1964. Vol. 3. p. 397. (In Russian)

- Gankina E. Detskaya kniga nashikh dney [The Children’s Book of Our Days]. Iskusstvo [Art]. 1968. No 10. p. 58., 65. (In Russian)

- Golos yaponskogo naroda [The Voice of the Japanese People]. Pravda. 1965. No 234. p. 1. (In Russian)

- Gosti iz dalekoy Yaponii [Guests from Distant Japan]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1956. 17 Nov. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Glazami khudozhnikov [Through the Eyes of Artists]. Nabor iz 20 otkrytok [Set of 20 Postcards]. Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik [Soviet Artist]. 1964. Otkrytka № 11 “Zhenshchiny i deti” [Postcard No. 11 "Women and Children"]. (In Russian)

- Glukhareva O. Novaya vstrecha s khudozhnikami Yaponii [A New Meeting with Artists of Japan]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1966. No 58. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Glukhareva O. Sovremennaya zhivopis’ Yaponii [Contemporary Painting of Japan]. Tvorchestvo [Creativity]. 1962. No 8. p. 21., 25. (In Russian)

- Glukhareva O. Yaponiya. Iskusstvo [Japan. Art] // Bol’shaya Sovetskaya entsiklopediya [Great Soviet Encyclopedia]. Moscow: Bol’shaya sovetskaya entsiklopediya, Ed. 2, 1957. Vol. 49. p. 629. (In Russian)

- Interesnaya vystavka [Interesting Exhibition]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1959. 18 Jun. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Ioganson B., Kuzina V. Pyat’ khudozhnikov Yaponii [Five Artists of Japan]. Broshyura k vystavke [Exhibition Brochure]. 1966. (In Russian)

- Iskusstvo v bor’be protiv yadernoy ugrozy [Art in the Fight Against the Nuclear Threat]. Iskusstvo [Art]. 1982. No 7. p. 74. (In Russian)

- Iskusstvo Vostoka v bor’be za mir i gumanizm [Eastern Art in the Struggle for Peace and Humanism.]. Katalog vystavki [Exhibition Catalogue]. Moscow: 1986. (In Russian)

- Kanevskaya N. Arkhitektura, izobrazitel’noye i dekorativno-prikladnoye iskusstvo Yaponii posledney treti 19 v. — 20 v // Iskusstvo stran i narodov mira: arkhitektura. Zhivopis’. Skul’ptura. Grafika. Dekorativnoye iskusstvo: Kratkaya khudozhestvennaya entsiklopediya [Architecture, Fine and Decorative-applied art of Japan of the Last Third of the 19th century — 20th century // Art of Countries and Peoples of the World: Architecture. Painting. Sculpture. Graphics. Decorative Art: Concise Art Encyclopedia]. Moscow: Sovetskaya entsiklopediya [Soviet Encyclopedia], 1981, Vol. 5. Pp. 672-673. (In Russian)

- Kanevskaya N. K istorii yaponskoy zhivopisi s 1868 po 1968 god [Toward a History of Japanese Painting from 1868 to 1968]. Gosudarstvennyy muzey iskusstv narodov Vostoka. Nauchnyye soobshcheniya [The State Art of the Peoples of the East. Scientific reports]. 1969. No 2. p. 41. (In Russian)

- Kanevskaya N. Sovremennaya zhivopis’ Yaponii. Avtoreferat dissertatsii [Contemporary Painting in Japan. Thesis abstract]. 1978. p. 15. (In Russian)

- Karten D. Volnuyushcheye proizvedeniye yaponskikh khudozhnikov [The exciting Work of Japanese Artists]. Literaturnaya gazeta [Literary newspaper]. 1955. No 36. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Khersonskaya E. “NET!” Fashizmu, “NET!” Voyne! [“No” to Fascism! “No” to War!] Inostrannaya literatura [Foreign Literature]. 1965. No 5. p. 238. (In Russian)

- Khirosima ne povtoritsya! [Hiroshima Won’t Happen Again!] Sibirskiye ogni [Siberian Lights]. 1960. No 3. p. 192. (In Russian)

- Khudozhniki mira v bor’be za mir [Artists of the World in the Struggle for Peace]. Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik [Soviet Artist], 1963. (In Russian)

- Kibrik E. A. Ob iskusstve i khudozhnikakh [About Art and Artists]. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Akademii khudozhestv SSSR. 1961. Pp. 122-126. (In Russian)

- Kibrik E. A. Podvig khudozhnikov [The Feat of Artists]. Tvorchestvo [Creativity]. 1959. No 8. Pp. 3-5. (In Russian)

- Kirov M. Sovremennyy realizm — tendentsii i perspektivy [Modern Realism — Trends and Perspectives]. Tvorchestvo [Creativity]. 1988. No 11. p. 3. (In Russian)

- Kist’ protiv bomby [The Brush Against Bombs]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1967. No 98. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Kolomiyets A. Podvig prodolzhayetsya [The Feat Continues]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet culture]. 1968. No 42. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Kolomiyets A. Podvig zhizni [A Feat of Life]. Khudozhnik [Artist]. 1968. No 5. Pp. 42-45. (In Russian)

- Kolomiyets A. Sovremennaya gravyura Yaponii i eye mastera [Modern Japanese Prints and its Masters]. Moscow: Izobrazitel’noye iskusstvo, 1974. p. 20, 29, 132. (In Russian)

- Kolomiyets A. Chtoby pomnili lyudi [For People to Remember]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1967. No 54. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Kolpinskiy Yu. Vvedeniye [Introduction] // Vseobshchaya istoriya iskusstv [General Art History]. Vol 6., Book. 1. Moskva: Iskusstvo. 1966. p. 20. (In Russian)

- Koretskikh V. Khirosima ne dolzhna povtorit’sya! [Hiroshima Must not Happen Again!] Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1959. No 73. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Levdanskaya N. Vystavka khudozhnikov Iri Maruki i Tosiko Maruki vo Vladivostoke [Exhibiton of Artists Iri Maruki and Toshiko Maruki in Vladivostok]. Iskusstvo Evrazii [Art of Eurasia]. 2023. No 1. Pp. 230-237. (In Russian)

- Maruki o svoyey rabote [Marukis about Their Work]. Iskusstvo [Art]. 1959. No 9. p. 77. (In Russian)

- Maruki I., Maruki T. Khirosima: Seriya panno laureatov Mezhdunarodnoy premii mira yaponskikh khudozhnikov Iri Maruki i Tosiko Maruki [A Series of Panels by International Peace Prize-winning Japanese artists Iri Maruki and Toshiko Maruki]. Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik [Soviet Artist], 1959. (In Russian)

- Maruki I., Maruki T. Protiv atomnoy bomby [Against Atomic Bomb]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1958. 10 Apr. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Maruki I., Maruki T. Protiv raskola mezhdunarodnogo fronta kommunistov [Against the Splitting of the International Communist Front]. Pravda. 1964. No 174. p. 5. (In Russian)

- Maruki T. Kartinki yaponskoy zhizni [Pictures of Japanese Life]. Sovetskaya zhenshchina [Soviet Woman]. 1958. No 8. Pp. 26-28. (In Russian)

- Maruki T. Zdravstvuy, dorogaya strana! [Hello, Dear Country!] Sovetskaya zhenshchina [Soviet Woman]. 1959. No 11. Pp. 44-45. (In Russian)

- Maruki T. Zdravstvuy, dorogaya strana! [Hello, Dear Country!] // Yaponskiye pisateli o Strane Sovetov [Japanese Writers About the Country of Soviets]. Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1987. Pp. 168-171. (In Russian)

- Maruki T. Stol’ko prekrasnogo! [So Many Beautiful Things!] // Sovetskaya zhenshchina [Soviet Woman]. 1953. № 6. Pp. 45-47 (In Russian)

- Maruki T. Stol’ko prekrasnogo! [So Many Beautiful Things!] // Yaponskiye pisateli o Strane Sovetov [Japanese Writers About the Country of Soviets]. Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1987. Pp. 128-132. (In Russian)

- Maruki T. Svet i teni yaponskoy palitry [The Light and Shadows of the Japanese Palette]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1966. 19 Apr. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Maruki T., Mun So Ney Z. Govorit Tosiko Maruki [Toshiko Maruki is Speaking]. Tvorchestvo [Creativity]. 1966. No 3. Pp. 12-13. (In Russian)

- Maruki T., Mun So Ney Z. Khirosima — perelom v moyem tvorchestve [Hiroshima is a Turning Point in My Writing]. Zhenshchiny mira [Women of the World]. 1967. No 1. Pp. 50-51. (In Russian)

- Matusovskiy M. Ten’ cheloveka [Shadow of a Man]. Ogonyok. 1966. No 51. Pp. 25-26. (In Russian)

- Mikhaylov N., Z. Kosenko. Yapontsy [The Japanese]. Moscow: Sovetskiy pisatel’ [Soviet Writer], 1963. Pp. 38-39. (In Russian)

- Moravia A. Atomnaya bomba i my [The Atomic Bomb and Us]. Kul’tura i zhizn’ [Culture and Life]. 1983. No 5. Pp. 42-43. (In Russian)

- Myshkin A. Yapontsy vo Vladike (Svetskaya khronika) [Japanese in Vladik (Vladivostok) (secular chronicle)]. Dekorativnoye iskusstvo SSSR [Decorative Art of the USSR]. 1990. No 11. p. 41. (In Russian)

- Muratov P. D. “Drugiye berega” ["Other Shores"] // Ideal i idealy [Ideal and Ideals]. No 1. Vol. 1. 2012. Pp. 152-165. [Retrieved August 23, 2023], (In Russian): https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/drugie-berega

- Muratov P. D. Soyuz khudozhnikov RSFSR [Union of Artists of the RSFSR] // Ideal i idealy [Ideal and Ideals]. No 4. Vol. 1. 2012. Pp. 175-188. [Retrieved August 23, 2023], (In Russian): https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/soyuz-hudozhnikov-rsfsr

- Nakanune otkrytiya vystavki indiyskogo prikladnogo iskusstva [On the eve of the opening of the exhibition of Indian applied art] // Kuznetskiy rabochiy [Kuznetsky Worker]. 1960. No 14. p. 2. (In Russian)

- Nikitina A. O sovremennoy natsional’noy zhivopisi Yaponii (po materialam vystavki “Shedevry nikhonga”). Tezisy dokladov k 14-oy konferentsii Vostochnogo kruzhka SNO [About Modern National Painting of Japan (on the Materials of the Exhibition "Masterpieces of Nihonga"). Theses of reports for the 14th Conference of the Oriental Circle of SNO.]. 1968. p. 15. (In Russian)

- Nikolayeva N. Iskusstvo Yaponii [Art of Japan] // Vseobshchaya istoriya iskusstv [General Art History]. Vol 6., Book. 1. 1966. Moskva: Iskusstvo. Pp. 425-426. (In Russian)

- Nikolayeva N. Sovremennoye iskusstvo Yaponii: Kratkiy ocherk [Contemporary Art in Japan: a Brief Overview]. Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik [Soviet Artist], 1968. Pp. 96-97. (In Russian)

- Nobuo I., Torao M., Taydzi M., Yosidzava T. Istoriya yaponskogo iskusstva [History of Japanese art]. Moscow: Progress, 1965. Illustration № 108. (In Russian)

- Novyye chleny akademii khudozhestv SSSR [New Members of the USSR Academy of Arts]. Iskusstvo [Art]. 1967. No 12. p. 76. (In Russian)

- Oblozhki i illyustratsii detskikh knig [Children’s Book Covers and Illustrations]. Detskaya literatura [Children’s Literature]. 1986. No 8. p. 64. (In Russian)

- Petrov A. Glazami khudozhnikov… [Through the eyes of artists…] // Kuznetskiy rabochiy [Kuznetsky Worker]. 1959. No 249. p. 3. (In Russian)

- Petrov V. Zametki o bratislavskoy biyennale [Notes on the Bratislava Biennale]. Detskaya literatura [Children’s Literature]. 1968. No 2. p. 56. (In Russian)

- Po vystavochnym zalam [In the Exhibition Halls]. Iskusstvo [Art]. 1959. No 7. p. 76. (In Russian)

- Po vystavochnym zalam [In the Exhibition Halls]. Iskusstvo [Art]. 1959. No 8. p. 80. (In Russian)

- Polevoy V. M. Dvadtsatyy vek: Izobrazit. iskusstvo i arkhitektura stran i narodov mira [The Twentieth Century: Fine Art and Architecture of Countries and Peoples of the World]. Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik [Soviet Artist]. 1989. Pp. 307-308, Pp. 342-343. (In Russian)

- Protokol zasedaniya Mezhdunarodnogo zhyuri Biyennale illyustratsii. Bratislava 1971 [Minutes of the Jury Meeting of the International Biennale of Illustration Bratislava 1971]. Detskaya Literatura [Children’s Literature]. 1972. No 1. p. 56. (In Russian)

- Raboty khudozhnikov Yaponii v Moskve [Works by Japanese Artists in Moscow]. Iskusstvo [Art]. 1966. No 7. p. 77. (In Russian)

- Rakitin V. Mezhdu budnyami i prazdnikami. O tret’yey Biyennale v Bratislave [Between Weekdays and Holidays. About the Third Biennale in Bratislava] Detskaya literatura [Children’s Literature]. 1972. No 6. p. 74., 77. (In Russian)

- S mysl’yu o materyakh. Katalog kollektsii proizvedeniy iskusstva sovetskikh i zarubezhnykh khudozhnikov [With the Thought of Mothers. Catalogue of the Collection of Artworks by Soviet and Foreign Artists]. Moscow: Sovetskiy fond mira [Soviet Peace Foundation], 1983. 33 p. (In Russian)

- S mysl’yu o materyakh [With the Thought of Mothers]. Kul’tura i zhizn’ [Culture and Life]. 1983. No 7. p. 31. (In Russian)

- Sal’nikov O. Khirosimskiy nabat [Hiroshima’s Alarm Bell]. Sovetskaya kul’tura [Soviet Culture]. 1968. 6 Aug. p. 4. (In Russian)

-Samoylo K. Desyat’ yaponskikh panno [Ten Japanese Panels]. Vechernyaya Moskva [Evening Moscow]. 1956. 13 Nov. p. 3. (In Russian)

- Samoylo K. Panno “Khirosima” [“Hiroshima” panel]. Vechernyaya Moskva [Evening Moscow]. 1959. 25 Jun. p. 2. (In Russian)

- Shmarinov D. Podvig yaponskikh khudozhnikov [The Feat of Japanese Artists]. Inostrannaya literatura [Foreign Literature]. 1957. No 8. Pp. 258-263. (In Russian)

- Svetlova N. Khirosima [Hiroshima]. Ogonyok. 1959. No 28. Pp. 14-15. (In Russian)

- Sovremennaya yaponskaya zhivopis’ [Contemporary Japanese Painting]. Katalog vystavki [Exhibition Catalogue]. Moscow: 1962. Pp. 3-4., p. 9., Pp. 14-15., p. 21., p. 30. (In Russian)

- Skul’ptor Vladimir Tsigal’ [Sculptor Vladimir Tsygal’]. Moscow: Sovetskiy khudozhnik. 1976. (In Russian)

- Starnovskiy B. Panno “Khirosima” — v nashem gorode [Panel "Hiroshima" — in our city] // Kuznetskiy rabochiy [Kuznetsky Worker]. 1959. No 249. p. 3. (In Russian)

- Tolstoy V. P. Sovetskaya monumental’naya zhivopis’ [Soviet Monumental Painting]. Moscow: Iskusstvo. 1958. p. 269. (In Russian)

- Veymarn B. Vvedeniye v iskusstvo stran Azii i Afriki [Introduction to Asian and African art] // Vseobshchaya istoriya iskusstv [General Art History]. Vol 6., Book. 1. Moskva: Iskusstvo. 1966. p. 409. (In Russian)

- Vinogradova N. Iskusstvo Yaponii [Art of Japan] // Bor’ba za progressivnoye realisticheskoye iskusstvo v zarubezhnykh stranakh [Struggle for Progressive Realist Art in Foreign Countries]. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1975. p. 302. (In Russian)

- Vinogradova N. Slozheniye modernistskikh techeniy v iskusstve sovremennoy Yaponii [Formation of Modernist Currents in the Art of Contemporary Japan] // Modernizm. Analiz i kritika [Modernism. Analysis and Criticism]. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1987. p. 224. (In Russian)

- Vinogradova N. A. Sto let iskusstva Kitaya i Yaponii [One Hundred Years of Chinese and Japanese art]. Moscow: NII teorii i istorii izobrazitel’nykh iskusstv Ros. akad. Khudozhestv. 1999. Pp. 197-201, Pp. 206-207. (In Russian)

- Vitalina T. Vystavki. Posle “Khirosimy” [Exhibitions. After “Hiroshima”]. Pravda. 1999. No 42. p. 4. (In Russian)

- Vladimir Tsigal’: Monumental’naya i stankovaya skul’ptura, risunki. Al’bom [Vladimir Tsigal: Monumental and Easel sculpture, Drawings. Album]. Leningrad: Khudozhnik RSFSR, 1989. (In Russian)