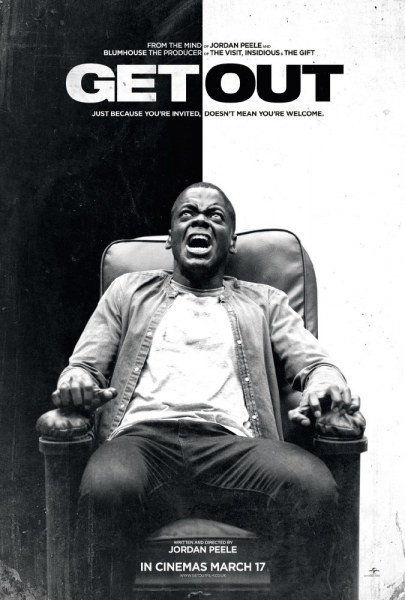

Review of the film "Get out", 2017. Horror, thriller, detective. Directed by Jordan Peele.

After reading the script, it became clear why most people loved the film and why critics wrote of the film that “it can’t help but like it”.

First of all, Jordan Peele has given a sharp social theme a new twist. The script lacks the classic denunciatory clichés inherent in dramas on similar themes. There are stamps of the thriller genre, but it is different and the author skillfully mixes them up, which plays into his hands.

Due to the peculiar humour, precision and subtlety of the presentation one reads not the racial hatred but rather the “black envy” towards African-Americans, and this can already be taken as a compliment. And it is for this reason that the picture feels fresh and light.

And, by the way, doubts about the fact that it is only about racism stem from thinking about the fact that all those white rich American elites choose African-American bodies for their continued existence. Hardly a racist could wish for such a thing, even considering that it is the body of a healthy, well-built, intelligent and evolved individual.

So yes, in my opinion, the author is pushing the boundaries here, and rather narrating xenophobia, although its manifestations are similar to cultural racism.

Alternatively, Peele is so revealing of the idea that it’s not slavery or torture or even death that’s most abhorrent to the protagonist, but existence in a “sunken place” — it’s like a new level of incarnation of slavery, where your body is controlled by a white man, only he does it by becoming you. And that’s when you lose your identity, your personality, but you continue to live. Horrifying, isn’t it? But it still doesn’t fit with racism in its purest form.

To ponder that, the Armitage family are not just racists, but rather intolerant bigots, makes their portrait and actions compelling. They suffer from delusions of grandeur, obviously identify themselves as part of the most privileged class, dispose of other people’s lives, all under the guise of “for the good of our community”. Ring any bells? The name of a man with similar views appears in the script.

And even the answer to the question “why black people?” plays for the “the film isn’t just about racism” team. Quote:

“Who knows. People want to change. Some people want to be stronger, faster, cooler. Blah, blah, blah, but don’t get me involved in that ignorant shit. I didn’t give two shits about race. I don’t care if you’re black, brown, green, purple…”

Secondly, interesting details and clues.

Already at the beginning of the script, we get clues, there’s a quote from the New Testament: "…present your bodies as a living, holy sacrifice…" and you involuntarily think, “Something is wrong, something is going to happen”.

Then there’s the kidnapping, followed by another clue: “United Negro College Fund. The mind is a terrible thing to waste.”

Fascinating, the story is addictive.

There are other great details (in the adaptation and in the script): the heroine in one scene drinks milk (a well-known symbol of innocence and purity, but our heroine is by no means pure, she is evil incarnate and we know it. Now, this is the kind of gimmick where subconscious dissonance arises in the brain. In Tarantino, for example, Hans Landa sips milk during an interrogation to find hiding Jews in the house), along with this, we read about the mother: how she carefully churns out the rhythm with a spoon on a dainty tea cup, first in the yard, then during hypnosis sessions, the “Run rabbit, run” soundtrack in the kidnapping episode, and the dirty dancing soundtrack (the time of my life) from a film about characters from different social classes, the scene in which the newly minted Andre shouts “get out” after a photo-op, etc. д. All these details are brought to mind and work for the story like a Swiss watch.

Then an ironically presented image of the family comes before us, and the author draws it already at the beginning of the story in the dialogue between Chris and Rose.

In an attempt to appear non-racist, the Armitages try excessively to conform to their image: the repetition of the phrase about Obama’s re-election, the refined smiles, the excessive politeness and politeness, the praise and exaltation of famous African Americans.

All of this already feels like a spectacle within a spectacle.

And we can’t help but think, “Something’s wrong”. Then there are the episodes with the “zombie” servants and the odd holiday in memory of the parents. It all holds or fuels interest in one way or another. And even the last-minute rescue and subsequent marvellous revenge episode, where the resourceful protagonist, thanks to chair padding earplugs, rewards the family with what they deserve, stands where it should. There’s an aftertaste of Tarantino style (but less gory), as if you’re watching Inglourious Basterds or Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, where retribution triumphs and history is rewritten, and all who suffered before are avenged and resurrected in glowing memory.

All this is fine, but the picture is not without its downsides:

⁃ Episodes with hypnosis

⁃ A brain transplant

⁃ The ending

All this in the context of this particular setting, to me looks like sci-fi with a claim to reality.

Yes, some might say that the story is about something else entirely, and that it doesn’t matter, and the hypnosis and the transplant and the, in my opinion, ridiculous ending. That these are just the tools the author uses to move the progress of the story and help us comprehend the main idea of the film.

But if these details move the story, then I suppose their importance is undeniable, and why then are they not worth talking about?

Suppose we ask the question, “What if?” What if everything is nice and coherent?

What if it managed to do it in one session, to wean the hero off smoking. What if it’s a new milestone in science?

It’s at this very point that my analytical brain resists, literally pulls me out of the narrative into reality and tells me it’s absurd.

That not everyone is suggestible, and that the chance that the protagonist is by some coincidence representative of a hypnotically influenced sample (indicated perhaps by his childhood trauma and openness) is negligible.

The minimum experimental trials are done one session at a time over a period of 8 weeks or more (this would apply to pain management, for example, or getting rid of bad habits). In this case, the percentage of results is in the 30% range.

This is where the theory of probability and scepticism comes into play. All in all, this kind of idea is like performing miracles in a sieve.

If hypnosis had such efficacy rates as in this film, I think at the very least the number of people with PTSD would have been reduced to zero, for example. And the world would probably be run by reptiloids led by Mark Zuckerberg.

Thanks to the setting, Blade Runner and other fantasy worlds don’t seem to be false, despite the hypotheses about the future. These pictures still feel like great fairy tales, and we don’t feel cheated.

Progress will probably reach the point of creating nexuses and flying cars at some point. But, again, doesn’t mean it will reach the point of creating artificial intelligence.

As for brain transplants, or the whole head if you like, that still sounds delusional. Admittedly, heart and liver transplants once sounded similar too. But it must be said that in the case of the brain, things are much more complicated.

The history of science records the experiments of American professor and neurosurgeon Robert White. In 1970, inspired by the work of Soviet biologist Demikhov, he transplanted the head of a monkey. The animal soon died.

So far, scientists have not been able to solve the problem of recreating the continuity of the spinal cord. How could the process of cell regeneration be triggered so that the head could receive impulses from the newly formed body?

Not long ago, Italian surgeon Sergio Canavero announced that a solution had been found. He claimed that several groups of inorganic polymers, called polyethylene glycol, or PEG, “can immediately repair mechanically damaged cell membranes”. Let’s just say that supposedly PEG can glue a torn spinal cord together, ensure impulse transmission, but only if the incision is surgically precise, clean (not torn).

Well, Canavero said that in 2015. It’s now 2022.

All the high-profile claims of progress and process are still just claims.

When it comes to transplanting parts of the brain, it is still not known in which area consciousness is localised, or if it is localised at all. Rather, we are talking about the integrity of this biological concept, and the idea of shoving part of someone else’s brain into a skull with the remains of another brain sounds insane.

The crux of my inner conflict as a viewer is this — this is not a sci-fi movie script, where perhaps hypnosis has already reached a high level and brain transplants have become a reality. This is a story about modern society, about the reality of the here and now, i.e. within a different setting the details voiced would not have attracted attention and would not have caused rejection.

These elements of fantasy do not allow the story to be played continuously with passion. A sense of deception prevents enjoyment of the viewing experience.

It’s as if sitting down to my favourite programme or football match, at the most crucial moment my player’s player hangs up or a player kicks ridiculously past the goal.

There is confusion, annoyance perhaps, and then you’re back on track.

The finale, on the other hand, looks like another zombie apocalypse adaptation.

Technically, it’s a happy ending, but it doesn’t bring tranquillity or satisfaction.

And here’s why:

— In all likelihood, after the experience, the hero will clearly revisit it again and again in his thoughts. (Another trauma).

— The rescue looks ridiculous. The friend stole the work car and drove himself — the motive is clear. Came because the cops refused to take him seriously and because he’s a good friend. But what happens when that mountain of bodies is found? Will they believe Chris’s story if they didn’t believe their friend’s story to begin with?

— Well, and, of course, most importantly: the characters go on with their lives in a world full of white people. Who knows if there’s another Armitage family like this somewhere else? Can anyone be trusted now at all?

To sum it up — to take on a problem that is as old as the world (and still relevant) but make the viewer look at it in a new way is the ultimate in screenwriting.

The script is packaged perfectly and is like a big box of wonderful gifts, with a couple of totally silly ones in it. Well, when have we ever liked absolutely everything that is given?