Istanbul Biennial 18 - between imperatives

Connecting the Istiklal pedestrian with the great piece of Renzo Piano, the Istanbul Modern, a broad street on the flank of the Galata hill is a small study of contrast. An ajar door clad in riveted, rusty iron plates is the kind of thing very easy to pass without a second glance. But inside, there’s a spacious courtyard, a kingdom of cats, and one of the venues of the 18th Istanbul Biennial, which has wrapped its first chapter in November. There was no signage on the street, so visitors had to follow the map or simply let themselves to carried by curiosity for cats (as the cats definitely have been running this particular part of the show).

This place behind the rusty door is a Former French Orphanage, an abandoned building and a neatly gentrified public pocket. As one of the autumn’s main venues it stood apart with a single artwork by Khalil Rabah “Red Navigapparate” (2025). This was the only part of еру curated program to be shown outdoors, as the only one built with living, organic matter, and certainly the most spectacular. In contrast to the rest of the Biennial, this artwork paradoxically mirrored it.

Rabah’s art intervention seemed to align its gestures to its meaning, to knock signifier and signified into one piece. The actual care for the relocatable plants tucked into those bright-red barrels not only symbolizes the urge to preserve what’s worth keeping, but literally provides shelter. Once a sequence of Istanbul’s ecosystem, the plants might just as well migrate and bloom elsewhere, so they are not symbolic references but actual actors of migration. But the integrity of the idea comes with a pinch of salt. Rabah’s project is responsive to the site, so it resonates with the echoes of the orphanage’s micro-social mechanics — protecting and restraining at the same time. And at last, if the piece is gathered from the outside, considered as a situation, it even produces its own kind of oppression: the alienated labor of the gardener, who had to re-dig the trench in front of the barrels every morning.

The non-summable

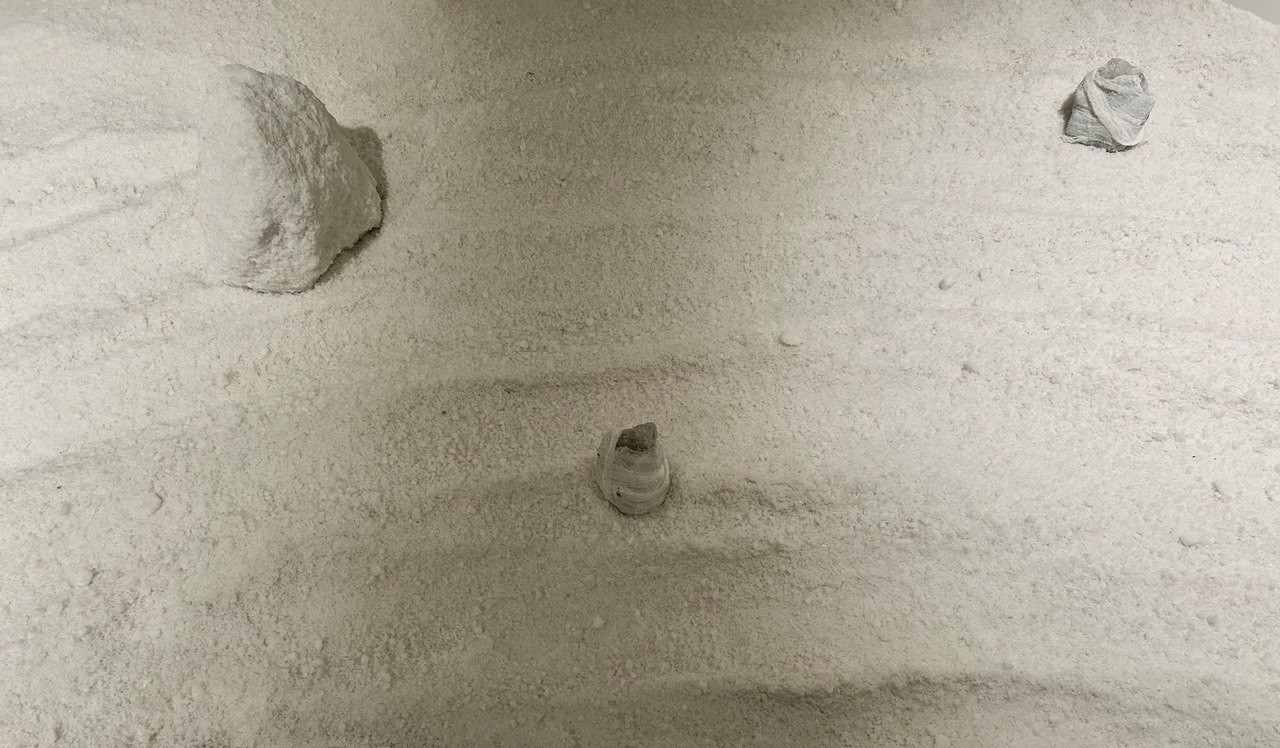

Wandering through all the venues revealed just how wildly different the themes actually are. Ola Hassanians “Whispering Dam” (2024) — a scaled sequence of a real hydraulic structure — the monumental, self-congratulatory giant built in colonial Sudan with zero regard for local traditions — it appears here as a gentle and quiet fountain. Ayman Zedani’s “Between Desert Seas” (2021) tells the story of endangered species in the Arabian Sea — the hump-back whale — through voices and audial textures. The clever move was to put this installation in the vaults of Galata Greek School, to scatter the salt for visitors to step on, to fill the basement with the spacious audio piece with stories and songs of whales, creating this bizarre echo though the city’s Byzantine undercurrent. Dilek Winchester rethinks an experimental writing system, based on many scripts practiced in the city, in “Istanbul alphabet” (2025). “Pacific Club” (2023) by Valentin Noujaïm traces the postmigration heritage of Paris through the interview and the psychogeographical camera-walk. This is just a small slice of the constellation that was on view.

Such a non-summable program may seem too chaotic and overloaded — but that’s the whole point of the curatorial approach here. By collecting all the pieces, arranging them in tense dialogue with the city, and keeping the venues walkable, Christine Tohmé succeeded in maintaining a delicate balance between various artworks and the body of the biennial. She let go of the curatorial control just enough, resisted the theorizing impulse, and refused to pin the artworks to any discourse, to pack them — she let them speak for themselves. There was even an open-call announce, so the parallel program was literally shaped by the artists and thinkers who came here to do whatever they think is important. The result of these curatorial decisions was a compassionate, diverse ecosystem that worked as a direct medium from artist to viewer.

The contextual

Such a freedom seems hardly believable between Scilla of the institutional machinery and Haribda of the current political climate in Türkiye, with its economic crisis and censorship that increased this year. After the arrests of the mayor, Ekrem İmamoğlu, and the head of Istanbul’s cultural heritage department, Mahir Polat, the clampdown feels especially tough. So, the Biennial’s claim to be a fortress of free expression is under real threat. But at the same time it had been squeezed by mainstream institutional expectations — by the very idea that a biennial should bring a conclusion, a verdict, a neat and simple theme to reflect on briefly, just by walking though the venues. So, avoiding the curatorial generalization and some politically sensible questions, the curator’s mission here is to deal with pressure coming from both the government and the biennial form itself.

Unfortunately, the balance doesn’t work — because there has to be the show, the venues have to make impression. So, while the artworks here are focused on postcolonial history of Sennar and the memory of Paris, the Istanbul and the precarious workers of the Biennial are on mute. Despite that blatant social inequality in this city is so brutal today that, just behind the people who came to admire contemporary art, there’s a child seeking for food in garbage on Galata Bridge. The first reason such images are excluded from the main program is the political climate itself — no doubt. But the second reason lies on the other side where contemporary art still has to be entertaining and spectacular, sewn-in the texture of ancient city on Bosphorus, represented within its labyrinth of narrow streets.

And yet, to be faire, despite all the pressure — both political and institutional — there was a nod, pointing at the alienation and exhausting labor, at the Turkish current social context (after all, at that gardener in the Former Orphanage). It came from the Kosovar artist Doruntina Kastrati, whose project “A Horn That Swallows Songs” (2025) is an image of the invisible labor inside Turkish lukum factories. The artwork consisted of two parts. The first was a giant metal structure recalling the validator at the entrance gate, with three screens showing video documentations from one such factory. The second was a tiny room with a single lamp and a vent, from which the sounds of everyday work played indistinctly — the subdued voices of the women workers covered with hails of supervisers. The ambience of labor so distant and so distinct at the same time.

Given all the artworks here, representing this whole constellation of freedom, compassion, and paralipsis, the first part of the three-year Istanbul Biennial ended up feeling a bit like meeting a three-legged cat itself. As Tohmé’s gentle conceptual framework, it’s not the product of some theorizing impulse, not a label, but a leading character — speaking of struggle, of the harsh and cruel circumstances, in which human and non-human are forced to live. A crippled cat — even if it’s hard to imagine this kind of fate for a cat in the city of such cat lovers — can be both a manifest and a kind of compliance at the same time.