Hard to Imagine. A Reflection on the Relationship Between Servants and Power

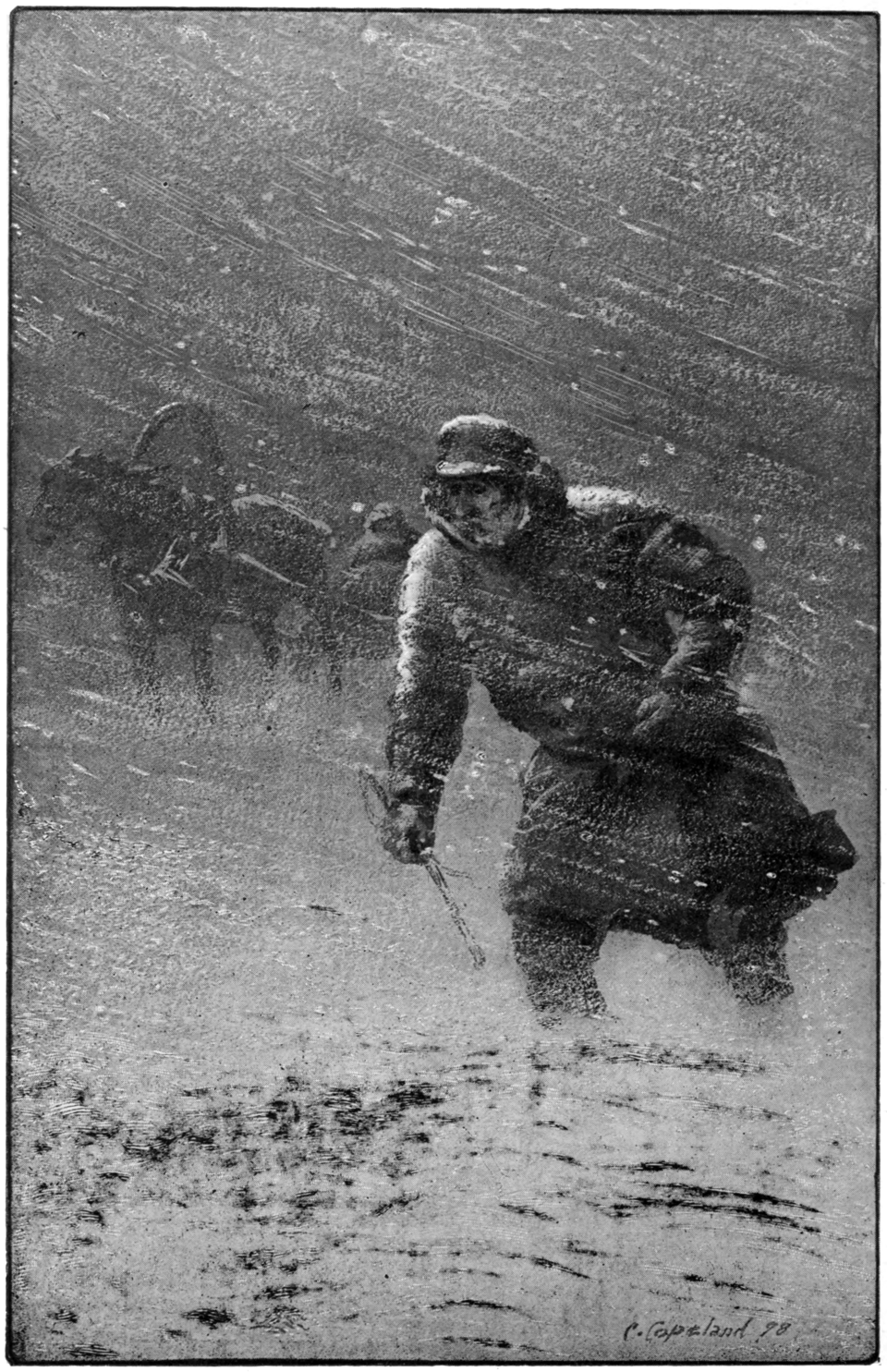

It is hard to imagine Elon Musk getting caught in a snowstorm, his car breaking down — and then saving his chauffeur’s life by sacrificing himself and keeping him alive with the last of his own body heat.

Yet in Tolstoy’s short story Master and Man (1895), that is exactly what happens: the merchant Vasily Andreyevich Brekhunov gives his life to save that of his servant Nikita.

The two only ended up in the snowstorm because the master insisted on travelling — eager not to miss out on a potential deal: the purchase of a nearby woodland plot, which other traders might otherwise snap up before him. Trading is Vasily Andreyevich’s great passion. He is willing to take risks and work hard for a good bargain — because he believes that is the only way he’ll one day become a millionaire. Nikita, a recovering alcoholic, receives part of his wages in the form of discounts from the company-owned shop. He accompanies his master out of sheer habit — he is used to not having an opinion of his own.

There are Jobs and there are bullshits Jobs. Ask Nikita, he knows all about it.

Twice they stray from the snow-covered roads and twice they end up, purely by chance, in a small village just a few kilometres from their actual destination. There, they warm up, but the master ignores the warnings of the locals and insists on pressing on — and Nikita, though reluctant, follows him once again, so accustomed is he to not asserting himself. They continue their journey and soon get lost again in the blizzard. The horse can no longer make headway — the snowdrifts are too deep, and small ravines begin to open up around them in the darkness. They are forced to spend the night in the sleigh.

At this point in the story, it is the servant who takes charge. He decides that they cannot go on, and the master complies without objection. Nikita makes camp as best he can in the snow beside the horse and, once wrapped up, doesn’t move again in order to preserve the little warmth trapped under his coat. The master attempts to sleep in the sleigh, but is soon overcome by terrifying visions. Eventually, he can bear it no longer, climbs onto the already exhausted horse and rides off into the dark, convinced that he is only moments away from reaching the forest — the object of his desire.

But he falls and only finds his way back to the sleigh because the horse has left tracks in the snow, guiding Vasily Andreyevich back. When he returns, he finds his servant close to death. After a moment’s hesitation, he opens his thick fur coat and lies on top of Nikita to keep him alive with his own body heat. But not only that: suddenly he feels joy and emotion, and he weeps as he realises what he is doing. In that moment, he understands that through this selfless act — which will likely cost him his life — he has restored meaning to his existence. A sense of fulfilment.

His final thoughts are filled with pity for another wealthy merchant — already a millionaire — who had only hours earlier been his role model. What use is all that money, Vasily Andreyevich wonders, and then freezes to death. Nikita loses three toes but survives — and lives on for another twenty years.

That Elon Musk might take risks for a business — even for others — seems plausible. But that he, like Tolstoy’s merchant, would selflessly save his butler’s life? Hard to imagine.

Elon Musk in a red Tesla, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/tesla-tesla-chef-musk-ist-fuer-die-autoindustrie-eine-unkalkulierbare-gefahr-1.3579767

Yet the fact is, he does have a butler. And not just him: there are butlers in the White House, ambassadors employ them, princes and princesses in Saudi Arabia enjoy their services, as do musicians — Madonna and Paul McCartney included. And while it may not be a daily concern to survive a snowstorm, anywhere in the world a butler could find themselves living a story like this:

The head of the house wants, after a long time, to take one of the many cars from his garage out for a spin. He sets off but, after a few hours, calls his butler in frustration because the car has broken down. Knowing what was likely to happen, the butler had already prepared a spare can of petrol in a second car and now drives after his employer into the dark night. Upon arrival, he silently endures the scolding. In butler jargon, moments like these are succinctly described as: “Take the banana.”

The boss hadn’t understood what the red warning light flashing insistently on the Bentley’s dashboard was trying to tell him. Shame and anger mingle. The butler is berated, and before the tank is filled with the reserve petrol, the boss speeds off in the butler’s car — unaware whether the butler will manage to refill the empty tank or if he’ll now need someone else to come to his rescue. This is what life can be like for someone working as a butler.

So why become a butler today? In an age when individuality and self-determination are prized above all else, the idea of setting one’s own needs aside for another person seems almost anachronistic. And yet, there are over two dozen academies worldwide that professionally train butlers.

The most prestigious is located in Simpelveld, the Netherlands. At The International Butler Academy, around sixty students annually undergo training in discipline, perfection, and loyalty — preparing them for careers that may lead to royal households, millionaire estates, or superyachts. There, they learn not only how to serve people impeccably, but also how to train packs of dogs and manage staff teams numbering in the hundreds — if required.

But why? Why enter a profession that conjures memories of pre-modern times, of servitude and absolute rule?

At the Simpelveld academy, no one calls themselves a “servant.” Trainees are butlers — and they aspire to be the best. They want to build careers and work in extraordinary places. They want to curate and stage luxury experiences. They want to serve a person or family, attend to their needs, and protect the lives and possessions of their employers if necessary. The focus of the training is not submission, but excellence in service. It is not about servitude, but about advancement. The profession is a vehicle: for discipline, for self-improvement — and often for a breathtaking career.

In the self-understanding of Western capitalist society, the individual is both a fashion and a product. Self-presentation is essential, both in private and professional life. Those who cannot present themselves well find it more difficult. Those who do not wish to be seen, are overlooked.

Psychologically elusive, the butler seems to contradict the spirit of the times. Yet, his ideals fit surprisingly well into a world that values achievement above all else: humility, loyalty, absolute professionalism. Those who do not live by these values leave the academy without a diploma—and without prospects of employment.

A warm and personal welcome to the Guest at "The International Butler Academy"

So, what does it mean to serve and see it as one’s calling?

A “friendly favour” is gladly done, as is a “love service.” It becomes more difficult with “service to the fatherland.” The “service in arms” is burdened with pacifist reflexes, which no longer seem to align with the current zeitgeist. From the position of those far removed from combat, we applaud the heroic courage of Ukrainians fighting for their homeland, willing to lay down their lives in its defence. At the same time, the German Bundeswehr is desperately seeking new ways to make “service in arms” attractive.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, carers who continued their work were hailed as heroes. From the perspective of those sheltering at home and fearing infection, these workers seemed like daredevils risking their lives to help others. A selfless service to society and to humanity. And simply a necessary aspect of the carers’ profession. Doctors in Gaza, environmental activists in the Amazon, rescue workers on ships in the Mediterranean—it seems that selflessness and willingness to sacrifice are such exceptional traits that they are difficult to handle: if someone appears psychologically unwell, it is considered trauma being heroically processed, or is the person truly a hero?

As a society, we evidently struggle to accept selflessness and dedication to a cause, outside of activism, careerism, or extreme situations like war, as something admirable or worthy of value. We tend to heroise and romanticise these qualities, treating them as something truly extraordinary. Only rarely do we recognise them as what they often are: a quiet, everyday attitude. Perhaps because they hold up a mirror to us: in a world that raises achievement and self-optimisation to the norm, self-denial appears alien.

“Sancho Panza” (from Don Quixote, Cervantes) follows his master on his harrowing adventures because he believes in the promise of rich rewards at the journey’s end. The promise of payment is repeatedly renewed and adorned with fresh appeal—understandably, Sancho Panza doubts its truth whenever he has once again borne the brunt for his master.

This dynamic is not outdated but structural: modern butlers are well paid. In exclusive positions, annual salaries of over €100,000 are common. Such careers exist: a former taxi driver who rose to become the chief butler of a Saudi royal household, now managing palaces and earning a princely wage.

From dishwasher to millionaire through hard and honest work. Butlers continue to uphold this motto with their dedication: it is possible if you work hard enough and keep smiling.

As in Sancho Panza’s life, a modern butler’s own life is far away: their own family must take a backseat. When the boss or lady calls, the butler leaves the delivery room and the church, missing the birth and wedding of their own child. It must be more than money driving someone to put their life so far on hold. Perhaps it is the feeling of being needed. Or the idea of being part of something greater—a world that shines. A life close to the stage, even if one never stands in the spotlight.

“I am the perfect servant. I have no life of my own,” says Helen Mirren as Mrs Wilson in Gosford Park. Her words resonate: must one deny their own life to serve well?

When the super-rich—such as the American billionaire and former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, who announced in early 2025 that he would use his private fortune to cover a nation’s contribution to climate protection—step in, it raises questions about the system of power distribution. If one person can cover the USA’s contribution from private wealth, then the same person could equip a militia, occupy a piece of land, establish administration and infrastructure, and provide a place for people to live. While no one wants to suggest such things, they lie within the realm of possibility when wealth accumulates to such extremes. Extending this thought, such extreme wealth dissolves the democratic understanding of state and politics. The mere possibility of such power reveals a system out of balance. And in this system, butlers do not appear anachronistic—but rather logical.

Butlers fit perfectly into this pre-modern distribution of power: they run the household. Complementing the team of servants are chambermaids and footmen, valets, chauffeurs, housekeepers and cooks, and if necessary, gamekeepers and dog handlers. They are the service staff of the plutocracy: discreet, loyal, efficient. They organise palaces, manage households, oversee operations — and in doing so protect not only people but power itself. Their job remains the same as in the 19th century: to provide freedom and time for their masters and mistresses. And, when necessary, to maintain the illusion that all this is deserved — earned through merit, style or charisma. The truth is simpler: it’s about possession. About access. About control.

The Writer of this Essay imagines himself being wealthy.

At the Butler Academy in Simpelveld, not only is technique taught, but also a certain view of humanity. It seems old-fashioned — a modern version of the gentleman of centuries past. And yet it contains elements that touch the heart: attentiveness, poise, dignity. Holding a door open for someone today can seem almost intrusive. But it can also be a sign of awareness. Of respect. In a society that mainly looks at itself, this might be a radical act.

A veteran butler who teaches in Simpelveld repeatedly asks the same question in his courses: What or who is a butler? This question is essential for every butler, and each must find their own answer, because only by answering it personally can one draw clear boundaries in professional life and reject intrusive demands.

The instructor’s answer is as simple as it is convincing: Butlers are people who can always give that little extra. This means that in their role, even when exhausted, they still smile; they serve a coffee on a tray with an extra touch, for example by placing a flower on the tray. They put that little extra attention into all the tasks they perform, tasks for which non-butlers rarely have the energy—or that drain energy because they seem so trivial and everyday. Yet it is precisely these seemingly insignificant actions that add a little extra appreciation to life and, in return, make life more worth living.

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Remains of the Day, the protagonist Stevens wonders at the start of his journey what makes a great butler, and he answers the question with an anecdote his father told him. His father, in the protagonist’s eyes, had the dignity that sets a great butler apart from ordinary ones. What he means by dignity he tries to explain, since even in the 1950s, the time in which the novel is set, the term was already losing its clarity. The son, himself a butler, uses an anecdote he often heard from his father. It concerns the household of an English Lord in India. One day, a tiger is said to have been lying under the dining table. The butler approached his lord and whispered quietly: “I am terribly sorry, sir, but there appears to be a tiger in the dining room. Perhaps you would permit the use of the calibre twelve rifle?” The lord agreed, the butler shot the tiger, and before the guests even realised the danger, the meal was served with only a slight delay.

This short story carries much of the colonial attitude: without fuss, the wild animal is slain and quietly removed. The beast from the wilderness that the Empire set out to tame and “civilise” is dealt with by the extended arm of the coloniser in the dining room, and no one notices. If the story continued, the tiger’s pelt would appear as a rug in the London townhouse, and the butler there would stumble over it on his way from the buffet to the dining table. The birth of a joke in Dinner for One was thus a very dignified servant who casually shot a wild animal in India with just two shots from a calibre twelve rifle, his pulse steady at 60 beats per minute. A heroic deed that is not heroic. Rather, the act of the subordinate would enhance the lord’s reputation when he returned to London and told tales of his overseas adventures, mentioning also his butler. The butler is summoned to demonstrate how he held the rifle, then receives an approving pat on the shoulder before retreating again to the subservience of his position. The lord, however, receives the applause — he is the hero who can claim such a servant as his own. What the servant accomplishes is really an act of his master. Besides, the heroic pose is anathema to the butler. Butlers are highly competitive racehorses: they want to outdo others and be the best by being faster, better organised, more resilient, more discreet and more loyal than anyone else. And with the casual shooting of a predator and, above all, the smooth continuation of the dinner after the deed, this butler has earned the title “great”. It is easy to imagine wanting such a person by your side: someone who never loses control or calm and who solves every problem with great ease. Also, there is always someone to blame for your mistakes — splendid. On particularly bad days, there is someone in the house to whom you can tell all your worries, while they, in turn, will never voice their own.

At first glance, the distribution of power seems clear: here is Elon Musk, billionaire, iconic. There, his butler — discreet, replaceable, always in the shadows. But the closer you look, the more the roles blur. Because power does not only show in possession, but in knowledge. And no one knows more about the daily life of the wealthy than their butler. With every day of service, the butler’s influence grows — quietly, invisibly, but steadily. He knows routines, preferences, secrets. He protects, prevents, directs. A badly chosen tie? A critical interview? The butler intervenes — before it becomes embarrassing. He books flights while simultaneously keeping a private jet on standby. He knows who is coming when, who must not be told what, and how to stage a silence that appears elegant.

A veteran and respected butler will be very clear when necessary, especially when it comes to protecting the family he serves: for example, he will forbid his employer from appearing before a camera if they are not in a suitable state for a public appearance. Is this power? Those who act like this need no insignia to display. They embody it already: trust, control, authority. And a knowledge of people more precise than any formal hierarchy.

The more a butler knows, the more he sees and understands, the easier it is for him to manage the family. They must conform to his regime to ensure a smooth operation. A butler may oversee several hundred household staff. Everything passes across his desk. The masters are organised without realising it. They become performers in the staging put on by their employees. The butler owns nothing, yet he runs everything. Every detail of family life goes through his hands. It quite literally lies in his hands. And eventually, the family cannot manage without the butler anymore, because they no longer even know how much they spend on their shopping, or how to refuel the car. From that moment on, it is the butler who is in charge. It is like a form of training that must never appear as such. For a butler, every day is about winning the game. The challenge each day is to deliver perfection. It is a thrill. An adrenaline rush in the world of the wealthy.

A butler has experienced the kick of a weapon pressed to his temple. For hours, he had to calm burglars demanding cash — in vain. The villa was luxurious, the butler loyal, but there was no cash. Eventually, the criminals left. The butler stayed.

Another had to refuse comforting closeness — to the daughters of the house. He knew emotional involvement would jeopardise his position. Distance is part of his professional ethos.

A third was asked to organise cocaine and underage prostitutes. He refused — and resigned. A fourth stepped down when he realised his employers’ financial arrangements were criminal.

The job demands a great deal. It requires the art of reading people and the clarity to continually question one’s own position and communicate it consistently. The role demands the willingness to protect both the physical and financial wellbeing of those served. Thus, butlers protect hierarchies. They settle within them and pass them downwards. They secure a very special position within a rigid system and enforce with military discipline the standards they themselves must adhere to from above. They are the enablers of the rich and powerful. Butlers only exist as long as there are structures that promote immense wealth.

They are servants of that power, protecting it and the wealth that comes with it because this is how they ensure their own existence.

It is easier to imagine that in the 21st century people choose the profession of butler than to accept that the structures making this profession possible still exist. People do all sorts of things to secure a slice of the pie, so why not serve? Few come as close to fulfilling the capitalist promise of a good life as butlers: they can touch it, they are present in the places where this promised life happens. And they are the ones who stage and guarantee the beauty and perfection of that promised life.

So? Who is truly free from the temptation to continue believing in the promises of capitalism?

Is a butler then not simply a far more authentic servant of power than any academic researcher with ambitions in academia, politics, or the cultural sector? Does a butler not have more clarity about their position, and more style, than Generation Z beginners trying to build a career without hard graft? Perhaps the butler is the embodiment of a question that concerns us all: Whom does my work truly serve? Who profits from me? And who extracts most of the value I generate?

The profession of butler becomes less difficult to imagine if one admits to serving a system where the needs of the many count for little — even though in a democracy it should be the opposite. Every click, every step of work, every purchase cements my role as a small, servile cog in the machinery of a system that wants only one thing: that I function — and consume.

It becomes harder to imagine what kind of societies the USA and Europe are heading towards: for if wealth is sufficient to wield politics, that is closer to arbitrariness, plutocracy, and tyranny than to sovereign republics committed to democratic ideals.

What do these admissions do to the perspective of a person who sees serving as their profession? The servant has lost the existential struggle for recognition to another. Someone else is recognised by them, seen, and affirmed in their existence. In return, the servant gives attention but remains invisible. Perhaps that is the highest price of service: not to be seen, even though one sees everything.

But let’s turn the question around: Whom do I serve if I am not a butler? Whose needs do I put above my own, and to whom do I diligently offer my labour in the hope of being lifted to a higher seat to become the one who receives recognition instead of giving it?

In a world where everyone was a butler but no one wanted to be master, everyone could be freer than in a world where everyone wants to be free, yet we are all slaves to a system that demands our services. Instead of a pursuit of self-fulfilment: mutual consideration. Instead of competition: care. A paradoxical ideal in a world that often confuses freedom with dominance.

Imagine Gulliver had discovered another island, inhabited solely by butlers of all genders. A society without police or laws — because everyone has learnt to hold back, to let others go first.

Perhaps that would be the utopia of lived anarchy: without power exertion, without subjugation. Or the exact opposite: a society frozen by politeness, where every step prompts a “After you, please” — until no one can move forward.

Who goes first when two butlers want to enter a restaurant at the same time?

How this island would really look is anyone’s guess. Perhaps the Butler Academy in Simpelveld is a first taste: a place where serving is taught not as humiliation but as an attitude.

Perhaps it is just a mirror of our society — a school for those who have learnt that power is not shown by loudness but by control. And that not everyone who serves is dominated — but also not everyone who rules is free.

Literature

Altmann, Robert

Gosford Park, 2001

Cervantes, Miguel De Saavedra

Don Quixote de la Mancha, 1605, Winkler Verlag Munich 1956

Ishiguro, Kazuo

The Remains of the Day, 1989, 2nd edition Heyne Verlag, Munich

Swift, Jonathan

Gulliver’s Travels, 1726, Insel Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main first edition 1974

Tolstoy, Leo

Master and Man, 1895, Anaconda Verlag, Munich