Between Shit-Jobs and Care Work

Alla Mitrofanova is an independent art critic and philosopher, a member of the group Cyberfeminist International and a curator of Philosophy Cafe (an open seminar dedicated to contemporary philosophy, which has been running since 2002 at the St. Petersburg Sound Museum). Her work is frequently published locally and internationally.

As part of the project “Political Dimensions of Cultural Praxis and Knowledge Production,” we are publishing Alla’s text on problems and potentials of self-organisation within the contemporary conditions of labour in the post-Soviet area.

Read more about the series — https://syg.ma/@sygma/political-dimensions-of-cultural-praxis-and-knowledge-production

Текст на русском можно прочитать по ссылке — https://syg.ma/@sygma/miezhdu-diermovoi-rabotoi-i-rabotoi-zaboty

Self-organisation, activism and cultural labour are impossible to separate during transitional periods from one sociocultural model to another. Such a transition is multilayered, it requires a renewal of ethics, new cultural codes and a reinvention of social institutions. The outdated model aims to ward off those new efforts and that way tries to preserve the impregnability of its institutions. David Graeber, in his book ‘Bullshit Jobs’ (2018) divides wage labour into two main categories. First, ‘bullshit jobs’ as managerial feudalism, wherein a small group that concentrates all financial resources hires well paid support staff provide its power with legitimacy and credibility and to control, humiliate and block initiatives of groups excluded of this professionalised realm. The other category is ‘shit jobs’, that are necessary to maintain human life and the quality of its existence. Doctors, teachers, waiters, janitors, artists, all fall into this category. The latter are overburdened with duties, self-exploitation and, most importantly, their work does not pay enough to maintain their own quality of life. As a result, the sociocultural system produces ruptures and traumatised groups of people. The civic response to the social catastrophe is an increase of volunteer helping activities, self-organised initiatives with alternative schools and self-support groups. These activities are completely excluded from the notion of work as well as from the financial share. But it is precisely this sphere that is developing and trying to build solidarity on the basis of new meanings. As a historical analogy, one can point to the increase of educated women and men at the end of the 19th century. They were unnecessary and dangerous to the system. At that time, it was difficult to imagine that these outsiders, once they increased in number, would become the basis of universal education, health care and science in the 20th century and enabled the industrialisation.

People that are producing alternative meanings were controlled not only in modern states. History has known burnings, denunciations of heresies, expulsion of dissenters since ancient times. This shows that meaning, concepts and codes have never worked as a separate realm of the ideal. Art has not always been the pleasure of the beautiful, instead, it has been shaping meanings and concepts and thus reality. Culture and ethics have always had a direct relationship to the materiality of the world: they set the parameters of social institutions, the rules of activity, the limits of self-reflection, and the forms of life. Those excluded from the cultural canon, without meaning or voice, have struggled for the right to represent themselves within the practices of culture and have sought access to political and cultural expression.

Art becomes political not in the sense of agitation, it shapes the limits of acceptance regarding meaning, value, coherence, perception and emotion

People that are producing alternative meanings were controlled not only in modern states. History has known burnings, denunciations of heresies, expulsion of dissenters since ancient times. This shows that meaning, concepts and codes have never worked as a separate realm of the ideal. Art has not always been the enjoyment of the beautiful, instead, it has been shaping meanings and concepts and thus reality. Culture and ethics have always had a direct relationship to the materiality of the world: they set the parameters of social institutions, the rules of activity, the limits of self-reflection, and the forms of life. Those excluded from the cultural canon, without meaning or voice, have struggled for the right to represent themselves within the practices of culture and have sought access to political and cultural expression.

During periods of paradigmatic shift, the notion of the political expands to include social relations, the notion of labour, art, technology, the body, and everyday practices. Thus, Marxists continue to speak of the problem of alienated wage labour, feminists — of the unpaid labour of motherhood, of care work and of the recognition of maintenance- and care professionals on which all existence rests. The notion of labour is increasingly less connected to the production of commodities and capital. The Operaists see labour as unproductive, as an exploitation of people’s creative and psychic potentials. According to David Graeber, economy is not an abstract model but an extension of anthropological processes, and labour must be understood not as the sole support for survival and consumption but as the meaningful activity of shaping an expected reality. Art becomes political not in the sense of agitation, it shapes the limits of acceptance regarding meaning, value, coherence, perception and emotion.

To understand labour not as wage labour within an already defined framework of capital, but as an activity that determines the shape of reality, allows us to speak of a transformation of reality, i.e. of the relations and structures of meaning in contemporary society. This materialises in alternatively organised social spaces and their unusual rules regarding labour. Although various researchers and activists write about this issue, in media the mechanisms of the ruling power manage to marginalise the problem and its political implications. Nowadays, there are no fires to silence dissidents, but there are many new filters regulating politico-economical sources and public access, as well as social tools to block the creation of research groups and the dissemination of ideas.

I will try to look at some self-organised formats that have existed mainly in St. Petersburg since about 5 years and are expanding their influence: volunteer education projects and feminist art groups, within which the following, seemingly different areas intersect: art, labour, politics.

A Few Examples of Self-Organisation

In 2016 students of the School of Engaged Art in St. Petersburg, founded by the members of Chto Delat art group, — Katya Ivanova, Nadia Ishkinaeva, Suzanne Oriordan, Alena Petit and Anna Averyanova — announced the Niichegodelat Institute (Research Institute of Doing Nothing) as a media project of a new social movement. A few months later, they teamed up with a group of cyberfeminists and marched in a column on May Day 2017. They spoke up against the meaninglessness of wage labour and began to radically experiment with working without the obligation to work, exhibiting without “artworks” and educating at parties. They critically reconsidered notions of work and declared the concept of “non-work”. “Non-work” radically rejects wage labour that benefits only a few, insists on joy and voluntary engagement and experiments with an alternative understanding of the labour process. Oddly enough, they produced a lot of texts, performances, exhibitions and conferences and had no less output than those who took their activities with the utmost seriousness. Furthermore, they now have allies in Moscow, who began to analyse the conditions of creative and volunteer labour and the exploitation of volunteer enthusiasm by large resourceful institutions.

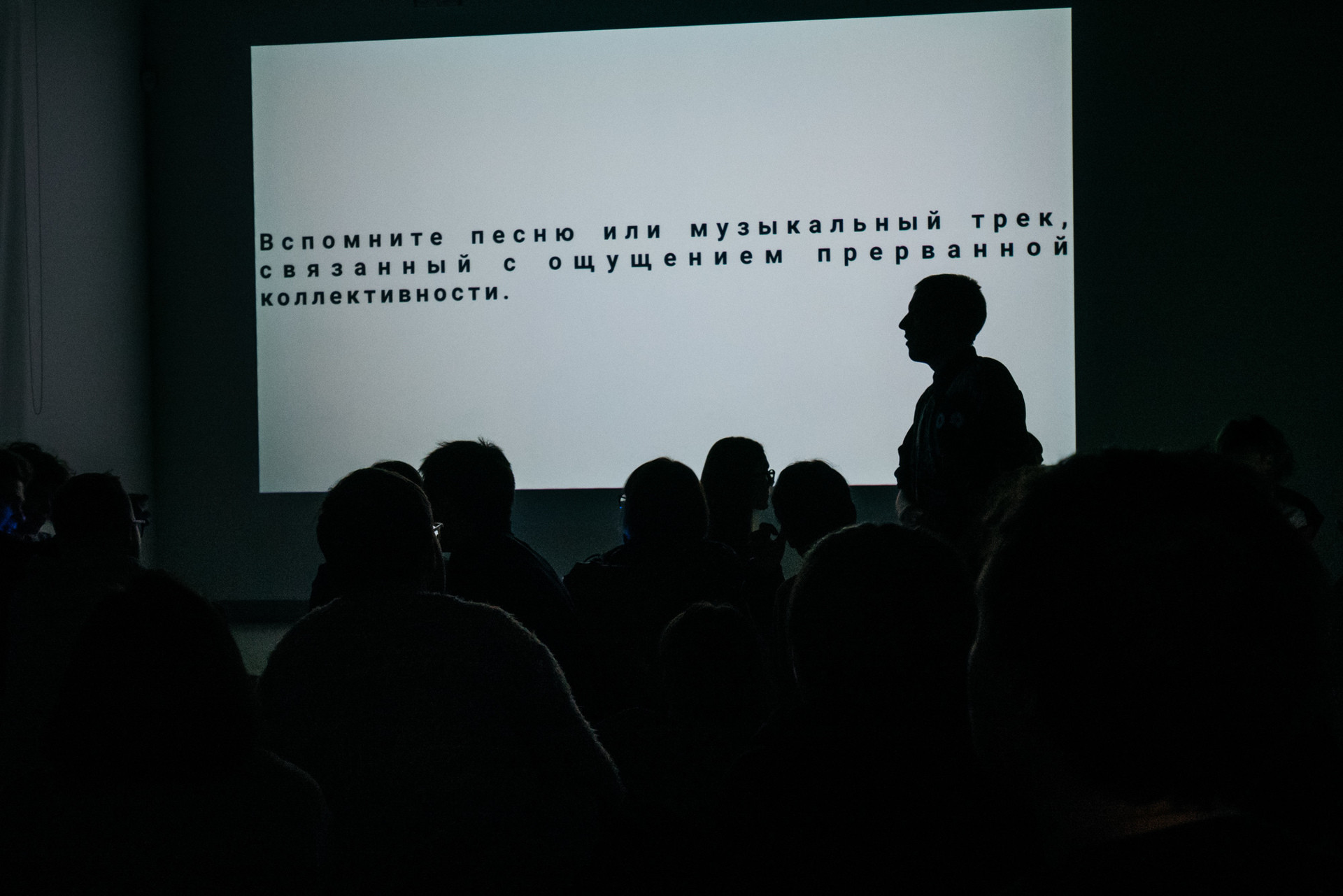

Around the same time in 2016, an art group from Minsk, founded by Alexey Borisionok (Minsk-Vienna), Olia Sosnovskaya (Minsk-Vienna), Nikolay Spesivtsev (Minsk-Moscow) and Dzina Zhuk (Minsk-Moscow) and, organised an annual festival, ironically titled WORK HARD! PLAY HARD! The festival’s participants explored the blurring of boundaries between work and rest, the personal and the political, the individual and the collective, practices of alienation and emotional labour, searching for a new form of collectivity, that can overcome the politics of control and management enacted by the authoritative state. The festival in Minsk had a divergent media and art component, but also fulfilled the role of an annual convention of like-minded people from different cities and countries.

In a similarly voluntary way, the Open Philosophy Faculty (OPF) was founded in October 2016, where philosophers who had been forced to leave the university, did not work but in their spare time offered special courses to students who were not studying anywhere but came together three times a week to listen and discuss. The initiator of OPF was the philosopher Ilya Mavrinsky, fired from the St. Petersburg State University because of his political activism. Around the teachers, a support group formed in order to do technical, administrative, and curatorial work. After 3 years, organizers wrote about the project: “OPF is becoming a community of professionals who implement various author’s projects and ideas in the space of public and free thought. The majority of our courses are held for the first time and are unparalleled in academic spaces. OPF brings together philosophers, psychoanalysts, political scientists, historians of science, sociologists — all those for whom dialogue, both with each other and with a public audience, is a necessity.” A significant feature of the OPF was the creation of a space of interdisciplinary overlap and discussion. Many psychoanalysts from different fields who had not previously communicated with one another finally got the opportunity to listen to each other for the first time. This also applied to philosophers, who had previously been confined to their school discourses and institutions. As videos of the lectures were regularly posted and informal discussions continued online, a networking community between the cities began to form long before the pandemic.

This indicates the formation of a fundamentally different sociocultural model, one that moves away from wage labour, away from a consumer culture

Needless to say, no one was paid and no one paid any money in such non-jobs, except for occasional donations. Yet all of these non-jobs are now over 5 years old. They are becoming interesting to more and more people, spawning “offshoots” and increasing community cohesion. New groups do not always understand where ideas and motivations come from, because the formation of a new field of meaning doesn’t occur necessarily in a conscious way. But the work of redefining the accepted meaning is creative and strategic. Philosophical blogs played a role in the consolidation of ideas in the first half of the 2010s: they provided directions towards relevant contents, reposted and translated texts. The blog called S357, maintained by translator and active member of a Philosophy Cafe Sergey Adashchik, is an example. In 2015 he published a translated excerpt from Nick Srnicek’s and Alex Williams’ book ‘Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work’ (2015). We can assume that this blog post and the series of discussions that followed theoretically supported the projects that emerged around this time. Interestingly, at the same time the American anthropologist David Graeber developed a book on the labour of care, analysing the anthropology and politics of labour in today’s world.

Among other supportive and framework initiatives we may list the Rosa (Luxemburg) House of Culture that was founded by the members of Chto Delat art group in 2013 in order to help self-organised cultural projects based in St. Petersburg. Syg.ma is also such an initiative — a decentralised platform that has existed since 2014. The authors' decisions — and everyone can post their own text here — are determined by the adoption of a field of meaning and the nature of the themes explored by the platform. For example, after several years of theoretical and practical workshops, the self-organised feminist project F-pismo (F-writing) created a major resource for experimental poetry here.

It’s important to notice that the problems of self-organisation in culture are similar to those of society as a whole. Any labour of reproduction, maintenance, social care or social rehabilitation of vulnerable groups is mostly unfinanced. Although the siphoning of financial resources from society makes it difficult to support crowdfunding for civic initiatives, they are growing in all areas from support for election campaigns to public education programmes. From time to time communities based on timebank principles are emerging — a direct exchange of services: “I’ll take your kids for a walk and you can teach me programming.” This indicates the formation of a fundamentally different sociocultural model, one that moves away from wage labour, away from a consumer culture. The theoretical models that are being proposed for the future are increasingly based on an universal basic income, self-organisation, satisfaction from meaningful labour on the principles of care, diversity and multiplicity of cultural spaces and varied types of education. These concepts appear less and less utopian. Due to rigorous analysis of labour and contemporary culture conducted by activists, these new concepts begin to replace previous institutions and present, during pandemic times, concrete political demands for an economic valorisation of care work.

Critical Addendum

Nastia Dmitrievskaya’s text on artistic self-organizations and in particular Boris Klyushnikov“s critique of their neo-anarchism and ‘demonstrative snobbish independence’ (both in Russian) seem to me like the legacy of the 2000s, when the competition for institutionalism seemed the only possible solution for life in art. After the political activation of civic life by the protests in 2012 [regarding the integrity of election] and particularly after the winding down of institutional dynamics in 2014 due to Crimea annexation, when foreign foundations supporting cultural diversity were cut, we now find ourselves in a more radical political situation due to the separation of social processes of brand new institualization and the standard state institutions. The creation of trade unions for culture workers is definitely necessary, but politically they only solve the problems of a very small group of artists and curators living in Moscow. The global problem is that in its present state the society lacks meanings, codes and institutions for cultural and social reproduction. The established hierarchy is not only economic but also cultural. Exclusive, neo-liberal cultures are incapable of social reproduction. They have neither the intellectual nor the social resources — the 1% is unable to think for the 99%. The commercial attitude towards art creates an inadequately inflated value for artistic work and at the same time devaluates human lives. To put it in Graeber”s terms, art becomes a bullshit activity, and the higher the cost of bullshitting, the shittier the existence. The reason for the frustration of the art community is not that the conditions of labour do not involve payment, but the choice between meaningless paid work and unpaid necessary work, which includes the work of artists — the formation of meaning. This situation forces self-organisation, but not as a means of eventual economic success, but because of the need to generate meaningful activity.

The political aspect of art and self-organisation is to introduce such a future as plausible and less intimidating and to invent cultural codes and methods to operate new anthropological arrangements

I admit that the very model of privileged competitive access to particular resources does not correspond to contemporary processes. But what can prevent the expansion of self-exploitation? It may well be that the only solution is the Universal Basic Income, which de-values and thereby frees up all forms of labour, allowing the meaning of labour and its areas of application to be redefined. If wages don’t entail the maintenance of survival, people have the opportunity to look for fields of application, to experiment with cultural self-organisation and to develop care-professions. This assumption can be illustrated by the growing demand for online education, social networking, and people feeling the need to be connected to places that generate meaning. The cost of education and all other care practices in the case of a basic income would be minimal, because the wages that secure survival would be separated from the wages of teachers, social activists, etc.

The history of feminism shows that the emergence of wage labour was accompanied by the legal infantilisation of women and other social groups as well as by their degrading to a silent, powerless “natural” inventory, which forced them into dependence on their employers or masters. Universal suffrage obtained only through birth partially restored the lost agency for women, proletarians, marginalised ethnic and confessional groups — literate or not. This right to vote was not so much about elections as it was about the restoration of the right to think and speak. This demand seemed absurd and unrealistic before the revolution of 1917, but within a few decades it became almost ubiquitous. But also economic security is a precondition of the right to the security of existence. Thus, the political aspect of art and self-organisation is to introduce such a future as plausible and less intimidating and to invent cultural codes and methods to operate new anthropological arrangements. As an example, the civil self-organisation in Belarus in 2020 or Sci-Hub [a web-site enabling free access to research papers] illustrate the power of such processes and models.