Who wrote Marx's Capital?

Introduction

The question of who speaks when we hear human speech — and who acts when we see human bodies performing actions with certain objects — is important for the demarcation between materialist and humanist worldviews.

The materialistic and generally scientific worldview, spontaneously materialistic in the kind of its practice, assumes that there are no causeless appearances. Every phenomenon, no matter how complex it may seem, always has certain reasons that led to its occurrence. The idea of causeless phenomena, or phenomena caused by spiritual entities — gods and spirits of various religions and shamanic beliefs — is not confirmed experimentally and contradicts the general theoretical foundations of the modern scientific picture of the world.

Ideas about causeless or caused by otherworldly forces apearances are based on the unknown nature of certain socially significant events, or the lack of awareness of listeners about them: the emergence of the universe, life, society and consciousness. At the same time, priests and theologians tend to speculate more often on the supernatural origin of the universe and life, as well as consciousness, since the recognition of the natural origin of all of the above undermines the faith of their flock in God’s omnipotence and leads to a reduction in their income: church tithes, donations, profits from the sale of candles and etc. Whereas apologists of capitalism more often insist on the unknowable or “natural” in the sense of non-social origin of consciousness, society and its norms, justifying private property and competition by natural selection; the existence of the state and the exploitation of wage labor — by the pack hierarchy; and bourgeois marriage, family beatings and rape are a painful legacy of sexual selection and the production of corresponding hormones in the body. At the junction between both trends, specifically thinking subjects have settled in, biologically justifying also the existence of religion as a product of natural selection, thereby ensuring the spiritual and ideological unity of the interests of the church and capital. At the same time, the interests of preserving profits and power relegate to the tenth plan the interests of objective scientific knowledge, which normally guides every scientist in his field.

Let’s consider a specific example: when a naturalist finds this or that object — say, the remains of Archeopteryx, then as a researcher he pays attention to dozens of details in order to establish the properties and origin of this object: the depth and composition of the geological rock where it was discovered; the expected movement of geological layers by which the object could have been transported from the place of its original origin; number, size and shape of preserved bones; the ability to reconstruct its appearance, lifestyle and origin — that is, its position in the system of ecological relations and place on the evolutionary tree of life. Whereas the possible social consequences — say, that the discovery of the skeleton of a feathered dinosaur may undermine someone’s faith in God’s plan and lead to a reduction in the income of a particular church — normally should not concern the researcher at all.

Of course, in reality, deviations from this norm can be very significant — the case of Giordano Bruno or Galileo on the one hand — and the case of Nazi scientists who perverted genetics to justify genocide — can be represented as polar in relation to this norm, between which there is a field of halftones, from honest and principled scientists to government "experts", careerists and charlatans.

Another important difference between science and ideology is that a scientist normally does not have the right to attribute his ignorance to an otherworldly or unknowable factor. The answer to the question about the reasons for the evolution and ecological position of Archeopteryx, given in a categorical and unsubstantiated form: “That’s how God created it!”, or “That’s how aliens from the planet Nibiru created it!”, or “That’s how my personal internal sensations created it!” — are not only unscientific, but also anti-scientific. In them, agnosticism moves to one form or another of obscurantism, to ideology — the philosophical justification of which is always one or another implicit metaphysics.

Who wrote Marx’s Capital?

However, let’s imagine that in place of the fossil skeleton of Archeopteryx, there lies in front of us some other object of more modern origin — say, a Russian translation of Marx’s “Capital”. And we, as scientists, are interested in the question of the origin of this object: how and why did it arise?

The answer that can usually be heard to such a question is well known to us all: Marx’s “Capital” arose because it was written by the outstanding German economist, philosopher and revolutionary, Karl Marx. From the fact that for some citizens Karl Marx may not be an outstanding, but a mediocre economist, or even an enemy of all free humanity, inspired by German statism, the world behind the scenes, or the Prime Minister of the infernal office, the archdevil Lucifuge Rofocale, as some theologists claim, the situation will not fundamentally change. "Capital" arose because Karl Marx wrote it.

Is this answer scientific? In the case of the fossil Archeopteryx, to explain the causes and ways of its occurrence, it is necessary to take into account dozens and hundreds of factors, consisting of two large groups: knowledge of the ecological niches to which natural selection adapts certain populations, producing species diversity from them; and knowledge of the evolutionary path traversed by the ancestors of a given species and its closest relatives. An exact analogue of ecological and evolutionary coordinates for biology in the social sciences are the terms synchrony and diachrony, introduced at the end of the 19th century by the French linguist Ferdinand de Saussure.

And if, to explain the origin of “Capital,” we reduce the actual diversity of factors operating in the social environment to one single name, then our answer is fundamentally no better than the answer of a biologist who, instead of explaining the evolution and ecology of a discovered species, would say with a thoughtful expression: “So God created it!"

It turns out that both “God” in the case of Archeopteryx and “Karl Marx” in the case of “Capital” are a way of blurting out ignorance of the many actual causes and factors that gave rise to this or that object.

Unfortunately, in this essay it is not possible to list all causes that led to the appearance of Capital and which are erroneously reduced to the personality of Karl Marx as their universal quasi-cause. However, it is quite possible to list groups of factors and their interrelationships, outlining a materialistic path of reasoning to search for the causes of social phenomena, in order of ascension from the abstract to the concrete.

I

So, before us is an object — a weighty book in a thick brown cover, on which the names of the authors are written in golden letters: “K. Marx and F. Engels”, and their profiles are embossed below. Having unfolded the book, we can find out that this is the 23rd volume of the collected works of Marx and Engels, 2nd edition, published in Moscow in 1960 by the state publishing house of political literature, and also that its circulation is 135 thousand copies.

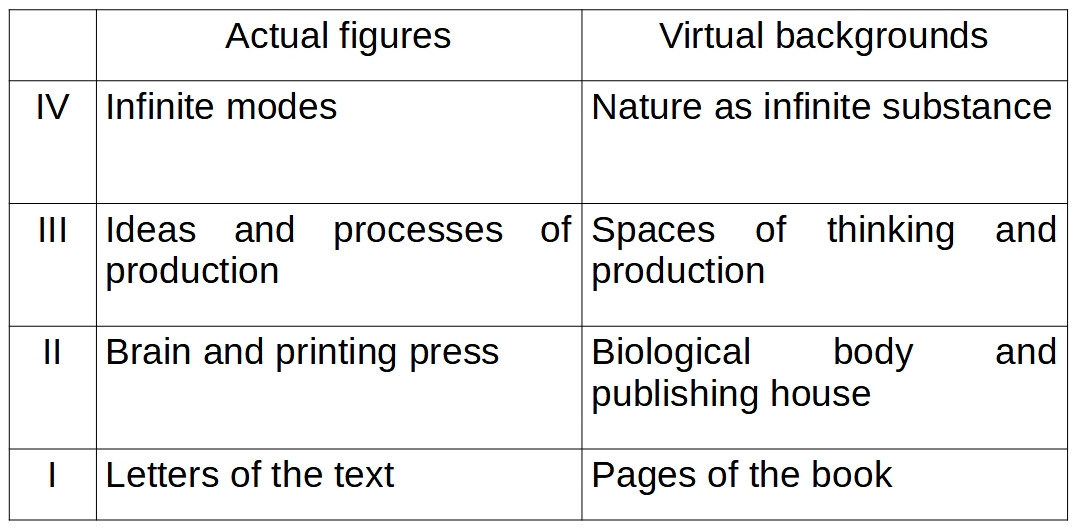

Opening the book, we can notice that it is a stack of white sheets of paper — more than 900 pages — on which letters are printed, arranged into words and sentences in Russian, as well as some comments in German, English and other European languages, plus illustrations. It would seem that this is an obvious thing for every reader, but it gives a basic difference between two opposites — the background and the figures distributed in it, that is, the space of nine hundred pages and the images printed on it.

An essential property of this object as a book, which allows it to be distinguished from other books, be it the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Robinson Crusoe, the Bible or Playboy magazine, is the order of letters and illustrations. The text of "Capital", printed on better or worse paper, on birch bark, papyrus, given as a text file or sounded as an audiobook, carries the same information as the one we are considering. And it is precisely to the text that the authorship of Marx and Engels is usually attributed, omitting further consideration of what is meant by them.

At the same time, although the properties of the text as a text are not determined by the medium, it still cannot exist without a medium at all, like the Christian or Neoplatonic Logos, hovering in airless space. The paper for the first manuscript of Capital, as for its first and subsequent editions, as well as the ink for the manuscript and printed editions, had to first be made before they could be used to express this or that set of signs that is the text "Critics of Political Economy". Therefore, further consideration leads us to the analysis of two processes: physical labor in the production of paper, ink and their productive consumption to create information carriers — and intellectual labor in the production of information itself, capable of being expressed in many ways in many languages of the world.

II

Taking into account the generally known information, it is not difficult to guess that the machine on which the productive consumption of ink and paper was carried out to print one of the one hundred and thirty-five thousand copies of the edition of Marx’s Capital in question was a printing press located in the building of the state publishing house of political literature noted above, and did not function without the participation of one or more employees of the said publishing house. Likewise, the machine by which the idea of Capital was fabricated was a conditioned reflex ring that passed through Marx’s brain, eyes and hands, and which innervated the gestures of the hand that applied ink to the sheets of manuscript.

Is it possible in this case to say that “Capital” as a book was produced by a printing press, and as a text — by Marx’s brain? It is clear that such an answer, although formally correct, remains too abstract. Of course, Das Kapital as a book was produced on a printing machine, not on a lathe or a loom; it did not grow on a tree and did not fall from the sky. Of course, it is the brain, and not the heart, not the spleen or the bladder, that is the organ of thinking with the help of which “Capital” as a text could and was produced. Should we, based on this, study the structure of Soviet printing presses, the anatomy and physiology of the brain in general and Marx in particular — despite the fact that preparations of the latter, unlike V. I. Lenin’s brain, have not been preserved -?

This is not to say that such research is completely useless — but it is possible to quite simply point out that it is a dead end: the paper, ink, set of pages, electricity, start and stop signals, combined in the printing press during its operation, come from a space external to it: from paper and ink factories, from a typesetting room, from a power plant, from a printer, whose work is supervised by many people, ranging from the immediate superior to the director of the printing house, above whom stands a whole hierarchy of civil servants, ensuring the coordinated work of various enterprises, designed to ensure their coordinated work, including the operation of the machine in question. Likewise, Marx’s brain, which innervated the gestures of his hands and eyes in the process of writing the manuscript of the Critique of Political Economy, was only a transmission link in the process of collecting, generalizing, comparing, criticizing and developing new information that came to him from all over society in many ways over the course of decades his individual development — in process of his assemblage.

Consequently, in order to understand the reasons for the operation of the printing press that prints the text of a book, as well as the reasons for the work of the brain that composed this text, it is necessary to study, first of all, not their internal structure, but the external environment, in the connection of which they produced concrete consequences, which are the subject of our consideration.

III

Let’s try to outline the extreme boundaries of the external environments that determined the work of the printing press and Marx’s brain. The limiting field for the first, obviously, is the entire set of technical and social machines involved in the process of mutual production, distribution and consumption, in which only the emergence of finite machines, like the printing press and the publishing house in which it was located, is possible. The extreme field for the second is the totality of social, and especially theoretical, relations that existed at that time, a selection of information from which became the material for the production of “Capital” as a text. And taking into account the fact that the subject of the study of “Capital” is the process of capitalist production, that is, that very “set of technical and social machines involved in the process of mutual production, distribution and consumption” that produced “Capital” as a book, we can talk about the mutual nesting of these two fields, suggesting mutual influence on each other.

In fact, the totality of technical and social machines expressed itself in Capital, theoretically, and in addition produced and multiplied its copies throughout the planet. But the opposite is also true: “Capital” as a scientific and political text inspired the most conscious workers of physical and mental labor to struggle, designed to radically change the system of social relations that produced it and which was expressed in it.

So is it appropriate to attribute this process, stretched over the surface of the entire planet and connected to many other processes, both on it and beyond its borders — since the functioning of society, for example, is impossible without the arrival of solar energy on Earth — only to Karl Marx as singular individual, that is, a humanistic abstraction, the criticism of which is directly devoted to the 6th of the “Theses on Feuerbach” (see also ru version "How to read "Theses on Feuerbach"?")?

“ Feuerbach resolves the religious essence into the human essence. But the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual.

In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations.

Feuerbach, who does not enter upon a criticism of this real essence, is consequently compelled:

1. To abstract from the historical process and to fix the religious sentiment as something by itself and to presuppose an abstract — isolated — human individual.

2. Essence, therefore, can be comprehended only as “genus”, as an internal, dumb generality which naturally unites the many individuals."

It is with such an isolated subject as the quasi-cause of all social phenomena that any humanism always deals, be it ordinary, from Feuerbach to Ayn Rand, or critical, from Karen Barad to Nick Land.

How, then, can one characterize this clearly non-human and impersonal process that gives rise to certain phenomena, the causes of which in humanism are attributed to human abstractions?

It seems that the most appropriate term in contemporary philosophy is the concept of assemblage, formulated in the joint work of J. Deleuze and F. Guattari in the second half of the 20th century and developed today by a number of researchers, including Manuel de Landa.

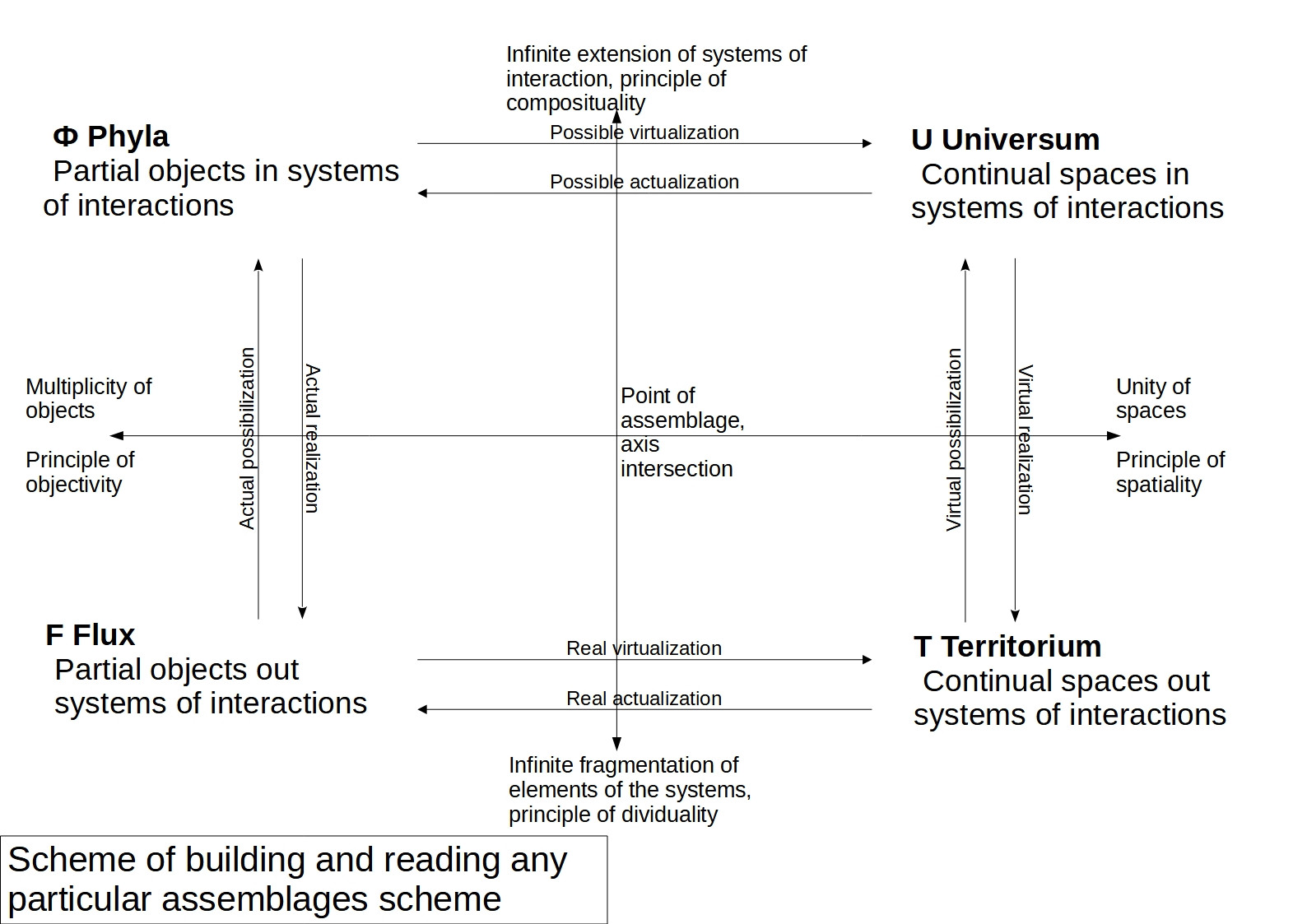

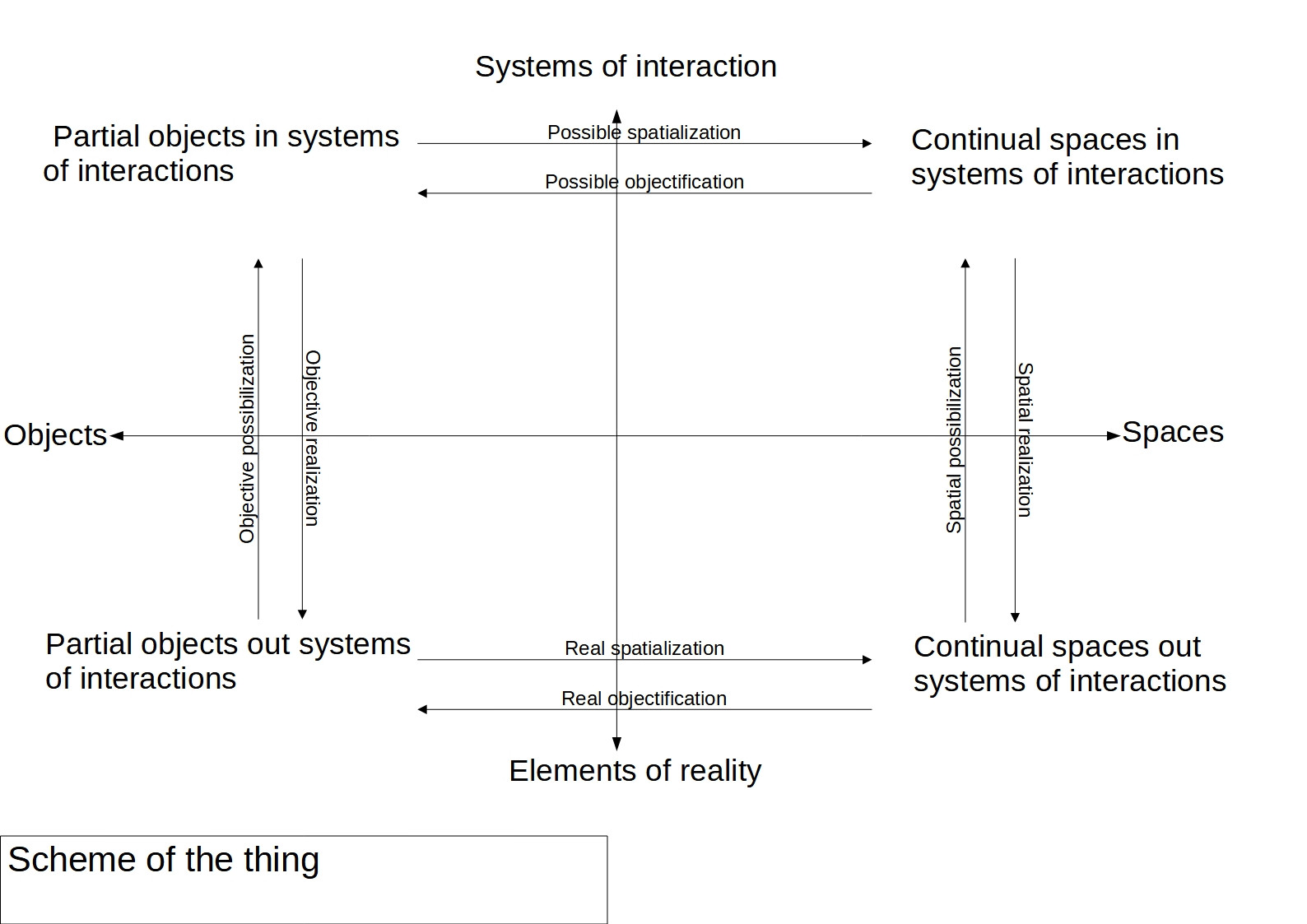

From the point of view of dialectical materialism, assemblage can be defined as a process of connecting and disconnecting two types of oppositions: actual figures and their virtual backgrounds; as well as realistic elements and systems of their possibilistic relations.

For example, a printing press as a technical device is a real connection of finite elements fixed in certain positions — and a publishing house or printing house as a public institution in the system of relations in which it operates will be an example of a possibilistic system. Similarly, for an individual book, the letters will be the actual figures, and the pages will be the virtual background in which the figures are located.

In fact, the classical definition of dialectics as a unity of oppositions, the relationship of which is both ascending and descending, does not specify which of the many possible oppositions are essential specifically for the materialist understanding of dialectics. Felix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze solve this problem by proposing a simple and effective method suitable for analyzing data from both social and natural sciences, since they reflect the real dialectic of the corresponding forms of movement of matter.

Then, for the assemblage of "Capital" and in general any text, painting, social action and similar appearances, the author to whom this appearance is attributed can be defined as an empty place through which this or that assemblage, named after this place, passed and was discovered .

In fact, Marx’s biological body, like that of any mental worker, can be completely divided into many elements, their positions, as well as the relationships between them. The brain, as an organ of thinking, occupies a fixed place in the body in the cranium in relation to the musculoskeletal system — but it also occupies a position in relation to the circulatory system, the peripheral nervous system, and so on. The same is true for Marx’s social body: his work as a journalist, philosopher, revolutionary, economist, was in a system of relations with the intellectual and physical labor of many other positions. There is not the slightest reason to assume that in addition to this multitude of elements acting interconnectedly, there was some additional individuality, a “self” — in a word, the renamed soul of Christian metaphysics, a single organizing center, not subject to cause-and-effect relationships, possessing free will and was the source of all Marx’s thoughts and actions.

In this case, is it even possible to talk about authorship if the real cause of the appearances under consideration is always one or another impersonal process? Since the author is only the place in which this or that assembly was discovered, the meaning of authorship can be compared with the way in biology new species and higher taxa are often named by the place of their habitat or discovery: African and Indian elephant, Madagascar lemur, Galapagos finches and so on. Therefore, the authorship of Marx and Engels in relation to Capital and other texts should be understood as an indication that these texts were actualized in the space of their intellectual activity, and not in the brain and activity of Isaac Newton or Saul Newman.

At the same time, the question of the existence of the assemblage before its discovery is debatable: did scientific socialism exist, and if so, in what form, before the raw theoretical material for it was combined in Marx’s head?

The possibility of such pre-existence is supported not only by general theoretical considerations, but also by specific facts: the discovery of differential calculus by Newton and Leibniz independently of each other; the independent discovery of the mechanism of the origin of species by Darwin and Wallace; the development, independently of Marx, of elements of scientific socialism among the Ricardian and Smithian socialists, as well as dialectical materialism by Joseph Dietzgen, clearly indicate that any scientific discovery or other manifestation of assemblages represents only a moment of actualization of previous processes distributed in the space of social relations.

IV

Is it possible to further examine the causes and conditions that made the emergence of Capital possible? Following the space of industrial, social and intellectual relations, taken as an actual figure, in this case one should consider the existence of an infinitely expanding virtual background: the biosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, the Earth as a whole, the solar system, and further up to the observable universe and unknown space beyond its boundaries, from which this universe arose and in which it exists.

We find ourselves in a problematic situation: following the direction of expanding the generality of the conditions that made it possible the disappearance of a single object, we go back to the idea of the infinity of nature, which in turn bifurcates into an innumerable number of objects external to a given universe, connecting and separating throughout eternity in all possible ways — and into the boundless space of their shuffling and recombination.

It should be noted that the concept of nature differs significantly from both the physical concept of the multiverse and from some modern philosophical concepts. The fact that nature is not a multiverse is clear from the fact that the concept of a multiverse assumes that universes, as regions of outer space with an ordered set of physical constants, like ours, are the highest type of objects, just as the atom was once considered the smallest type of objects. However, there is no reason to suggests that even if all the space outside this universe is filled with other universes, the latter do not combine into objects of a higher order, and those into even larger objects, and so on — just as an atom is not only divided into an unknown number of levels down, but is also capable of forming molecules, those — intermolecular ensembles, and so on. And just as the variety of molecules and elementary particles convinces us of the variety of possible micro-objects in addition to individual atoms, there is also no reason to assume that the variety of macro-objects outside the observable universe is exhausted by universes similar to it, differing only in a set of physical laws.

Regarding the philosophical concept of the materialist absolute as hyperchaos, formulated by Quentin Meillassoux in After Finitude, along with interesting discussions about correlation, he states that nature as a whole is destructible: “In so doing, I claim to know that the world is perishable, just as I know that this book is perishable." From further reading it is not difficult to see that in general the concept of the absolute as hyperchaos is built by him according to the model of a “destructible absolute”.

And this is obvious nonsense, refuted already in the 5th century BC, by the ancient materialist philosophers Democritus and Epicurus:

a. Nature as a whole cannot collapse, because destruction is disintegration into parts outside — but there is nothing outside nature, therefore it cannot die through decay.

b. If nature could perish, then during the countless time preceding this moment it would have collapsed long ago, and we would not be talking about it.

The ancient Roman epicurean Titus Lucretius Carus writes about the same thing in the poem “On the Nature of Things” (De rerum natura):

"For lapsed years and infinite age must else

Have eat all shapes of mortal stock away:

But be it the Long Ago contained those germs,

By which this sum of things recruited lives,

Those same infallibly can never die,

Nor nothing to nothing evermore return."

It is true that nature, as an infinite substance, is constantly destroyed and restored in its parts, but to assert that it as a whole can perish is clearly a false statement. Similarly, Meillassoux’s thesis (see also ru version of the article "Materialism without materialism. Critique of Quentin Meillassoux") about the possibility of spontaneous changes in physical constants and other laws of nature is a bad abstraction, since the laws of certain systems do not exist without a carrier — which means that in order to change the laws of motion, the composition or structure of the carrier must change — say, the physical vacuum for the universe as a whole; species or chemical composition for the biosphere; level of productive forces for society. Specific changes for biological and social systems are well known and observable. We can assume the possibility of changes for physical laws — if parts of the universe come into contact with some other parts of matter that can have a significant impact on them. But such changes will always have a cause, and will also be caused by a change in the ratio of parts and wholes in changing systems.

However, at this stage of development of physics and cosmology, reasoning about what can happen when two universes collide, whether the values of physical constants in them will change, and if so, how, is a direct path into the metaphysical swamp of empty speculations.

A truly philosophical question is the study of the relationship between interpretations of nature as an infinite number of parts, objects or modes — and nature as an eternal and limitless space of their shuffling. Perm philosopher Vladimir Vyacheslavovich Orlov, in his 1974 monograph “Matter, Development, Man” proposed to distinguish between these interpretations as extensive and intensive concepts of materialism, leaning toward recognizing their intensive unity.

The Deleuzo-Guattarian concept of assemblages allows us to concretize this idea by conceiving the existence of both aspects of this infinite nature in their dialectical unity. As two examples of actualist deviation from the dialectical unity of the actual virtual, Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory (ANT) and Graham Harman’s object-oriented ontology (OOO) can be mentioned. The first of them states that everything that exists is divided into actual objects, whose existence is manifested in their activity — and into a network of their interactions. What Latour does not take into account is the fact that not all spaces are in the form of networks — there are hierarchical, genetic, nomadic, rhizomorphic and other types of spaces, as well as all sorts of combinations of them, clearly different from simple interactions between actors, and to them irreducible. Graham Harman goes even further in the direction of actualism, claiming that there are no spaces at all, except for the space of individual objects contemplating the wholes and parts of each other. Such contemplative realism aggravates the error of contemplative materialism by excluding the concept of matter as a substance of which actual objects are modes.

From the point of view of classical Marxism, both actualist interpretations are not just erroneous — their erroneousness is caused by the class position of their authors as bourgeois intellectuals who welcome the achievements of liberal progress, but do not think about either its costs or the possibility of its qualitative overcoming in a communist society. At the same time, the philosophically actualist bias is identical to the extensive interpretation of matter as a collection of individual parts, defended by such Soviet authors as K. P. Shapovalova (“Content and methods of scientific substantiation of the principle of the unity of the world” (Kyiv, 1967)), which was opposed by V. V. Orlov in the work mentioned above.

Returning to the original question, can we then say that Marx’s Capital, together with Marx himself and the capitalist mode of production by him explored, are produced by the same infinite nature, existing as a dialectical unity of itself and its countless modes? In short, yes, and anyone who claims the contrary will be forced to attribute the cause of Capital to Marx as an “abstract — isolated — human individual” as an ideological expression of the peculiarities of the existence of the petty bourgeoisie, an interpretation that Marx himself clearly spoke out against twenty-two years before the publication of the first volumes of "Capital".

However, such an answer, being essentially correct — just as it would be essentially false to point to a human, god or spirit as the cause of this or that phenomenon — would at the same time be empty and meaningless without examining the specific mechanisms and stages of this production.

Philosophical preparation of the research space is only a condition of the research itself. And here we return to the idea of psychosocial micromechanics, which expands the Marxist idea of a materialist understanding of history. Its version, formulated by Marx and Engels and further developed by Plekhanov and a number of Soviet historians for major social phenomena, such as the emergence and death of historical formations, wars and revolutions, briefly summarized by the formula “The state of the production base determines the state of the system of social superstructures”, leaves outside the framework consideration of cause-and-effect patterns characteristic of superstructural and microsocial phenomena in general. We can say that this situation represents a virtualist bias in theory, the opposite of the actualist one discussed above.

Attempts to overcome this problem have been made within the framework of Marxism repeatedly, starting with the attempts of the first Freudo-Marxist synthesis of the 30s, undertaken by Adler, Reich, Marcuse, Adorno, Horkheimer, Fromm and others, and to the present day — since many modern theorists are actively trying put the achievements of actualist philosophy, be it the aforementioned OOO and ANT, or Timothy Morton’s "Dark Ecology", Levi Bryant’s onticology and much more, at the service of the struggle against capitalism. The lack of significant success in this field is due to a number of reasons, not the least of which is the illiteracy of theorists and activists who took up the solution to this problem. And without eliminating this illiteracy both in the history of philosophy and in the modern sciences, one can hardly expect rapid progress in improving historical materialism in relation to the explanation and engineering of microsocial phenomena.

To summarize, the stages of consideration of the levels of possibility, the implementation of which was the considered copy of Marx’s “Capital” of 1960, can be summarized in the form of the following table:

This table, outlining the limiting boundaries of consideration, at the same time allows us to pose an additional and, in a sense, redundant question about the structure of the middle — average in relation to the limits of the processes of logical reasoning that took place in the intellectual activity of Marx and his immediate circle, attempts to study which in the Soviet period took the form of a number of monographs, united by the theme of “The Logic of Marx’s Capital.” Well-known works in this direction undertaken by Zinoviev, Ilyenkov, Vazyulin and a number of other authors today constitute significant theoretical material, in the understanding of which, however, significantly greater progress is possible than was achieved in the Soviet period — as the very dialectical method of ascent from the abstract to the concrete, expressed in capital, can and should be concretized thanks to the achievements of assemblage materialism and other significant ideas of modern philosophy.

Conclusion

The occasion for writing this article was a series of friendly discussions, which can be grouped as follows:

First, a discussion with comrades from the Socialist Alternative about the possibility and necessity of preserving the legacy of orthodox Marxism in the process of developing modern science and philosophy.

Secondly, discussions with the philosopher and left-wing accelerationist M. Fedorchenko about the relationship between modern trends in philosophical thought and orthodox Marxism: is it not a form of dogmatism to assert the existence of a single process that goes back from Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky through Freudo-Marxism to the ideas of Deleuze and Guattari and new ontologies while preserving the achievements of orthodox Marxism?

Thirdly, a discussion with comrades from the spichka.media discussion club about both individual questions about the meaning of authorship and the associated category of subject, and a recent article about the philosophical path of Abram Deborin, which my comrades invited me to evaluate.

Essential for clarifying all three discussions, it seemed to me a more clear presentation of my own position of dialectical materialism as an ontology of assemblages using a concrete example, to which none of the interlocutors is guaranteed to remain indifferent.

I see the further course of the discussion in the light of clarification of three aspects essential for the development of Marxist thought: method, theory and practice.

1. About the method

“There is need of a method for finding out the truth” says the fourth of “Rules for the Direction of the Mind” by Rene Descartes. And this remark is more than relevant for materialist dialectics, a century and a half after its emergence, which is still not clearly and distinctly formulated as a definite method. Therefore, it is not surprising that if among outstanding dialecticians such as Hegel, Marx, Lenin, Deleuze and Badiou, it is not reflected as a method, but is found only in application to certain subjects, then among average theorists of Marxism it is found from fifth to tenth, and among ordinary agitators, politicians and activists it exists in the form of separate statements, at best helping to correctly grasp the relationships of individual opposites, and at worst sliding into outright sophistry and verbiage, as in the notorious in russian Youtube discussion about the “dialectic of a hare and a stool”.

The philosophical justification for this dead end today is Ilyenkov’s interpretation of dialectics as a theory of knowledge, and not as a way of moving the oppositions themselves in developing matter, of which cognitive processes in society are a part. Critique of Ilyenkovism as a positivist and generally subjective-idealistic bias in philosophy is therefore one of the conditions for approaching the problems of dialectics as the ontology of moving matter in general and the methodology for the development of social forms of matter movement in particular.

At the same time, it is strictly not enough to note that Ilyenkov or another thinker was right on some issues and wrong on others. The essence of the matter is to find out what physiological, psychological and social reasons were combined in him to produce this and not another statement or action.

From here follow the first two comments on the article “The Philosophical Heritage of Abram Deborin”:

Firstly, it is not explained what Abram Deborin was behind the phenomenon — whether he means an abstract individual of humanistic ideology, or whether the author is meant as the place of manifestation of this or that assembly, as follows from the provisions of materialist philosophy.

Secondly, further consideration of the life path and intellectual figure ity goes more in line with the critical humanism of the Marxist version than is presented from the standpoint of materialist dialectics. Indeed: Deborin, as a philosopher, undoubtedly studied and developed materialist dialectics as a theory of the unity of oppositions (we omit consideration of other definitions of dialectics for now), which is discussed in the article. However, what oppositions were combined in Deborin’s intellectual activity and expressed in his works — it would be extremely difficult to find out from the article.

Both shortcomings of presentation expressed in this article, that is, the vagueness of the subject and the unclear order of research, in turn are explained by the underdevelopment of materialist dialectics as a method.

As materials for discussing the possibility of its development, I would recommend starting with a consideration of the compact and practical works of Rene Descartes: the already cited above “Rules for the Direction of the Mind” (which it would be nice to comment on and schematize), as well as “Discourse on Method” and “Principles of philosophy". As for my own works on Cartesian philosophy, among the published ones I can point out “The Materialism of Radical Doubt” and “From Subject to Rhizome”, to which are adjacent “Criteria of Metaphysics” and “Four Aspects of Assemblage”.

2. About theory

The third remark to the entire plan of the series of articles on the history of Soviet philosophy is its clearly insufficient connection with modern theoretical issues. Of course, the study of the philosophy of a number of Soviet authors and schools of dialectical materialism is important in itself. However, it has already been shown above how the problems of extensive and intensive definitions of matter, considered by V.V. Orlov, fit in with the problems of modern Western philosophers Bruno Latour and Graham Harman.

Therefore, it seems to me that a more specific and relevant way of considering the history of Soviet philosophy would be to consider it in connection with the ideas of modern authors who need materialist criticism and extracting rational grain from their texts, of which the following can be listed:

1. Nick Land — philosopher, representative of right-wing accelerationism and ideological anti-humanism, mixing the concept of a body without organs and the full body of capital, promoting the ideas of the eternity of the market, as well as the inevitability and desirability of the death of the so-called. “humanity” due to the development of productive forces in the form of hostile artificial intelligence. The latter is one of the most serious mistakes among his ideas, since if he hates all people and wants their speedy extermination, then it is clear that he recognizes their real existence, that is, he is a humanist. Significant works: collections Fanged Noumena, Cybergothics, CCRU Writings 1997-2003.

2. Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams are philosophers, representatives of left accelerationism, who envision the onset of world communism mainly through the purely technical development of the productive forces and with minimal participation in the political struggle of the working class. Significant Works: The Accelerationist Manifesto, Inventing the Future.

3. Brian Massumi — philosopher and translator into English of texts by Deleuze and Guattari, interpreting their concepts, in particular becoming-animal, in a humanistic way. Significant works: A Guide to Capitalism and Schizophrenia, What Animals Teach Us About Politics, The Politics of Affect, Ontopower.

4. Timothy Morton — philosopher, representative of "dark ecology". Significant works: Hyperobjects, Dark ecology, Going green, Hyposubjects.

5. Bruno Latour — sociologist and philosopher who develops actor-network theory. Significant works: We have never be modern, Pasteurization of France, Reassembling the social, Where to land: politics in a new climate situation.

6. Quentin Meillassoux — philosopher and speculative materialist. Significant works: After finitude, Divine non-existence, Number and siren.

7. Graham Harman is a philosopher who develops the ideas of object-oriented ontology. Significant works: The Quadruple Object, Speculative Realism, Prince of Networks.

8. Ray Brassier is a philosopher who develops the ideas of transcendental nihilism and a uniquely understood dialectical materialism. Significant works: Liberated Nothingness: Enlightenment and Extinction.

9. Levi Bryant is a philosopher who develops ideas of onticology that approach the materialism of assemblages. He wrote the blog Larval Subjects. Significant Works: Democracy of Objects.

10. Manuel de Landa is a philosopher who develops the Deleuzo-Guattarian idea of assemblage materialism, also known as the theory of assemblages. Significant works: War in the era of intelligent machines, New philosophy of society, Philosophical chemistry.

11. Andrew Culp is a philosopher who develops the ideas of Deleuzian communism. Significant works: Dark Deleuze.

12. Reza Negarestani — Iranian philosopher and engineer, in the early period of his creative work he published the philosophical novel "Cyclonopedia"; Recently he has been developing the ideas of neo-rationalism. Significant works: Cyclonopedia, Intelligence and Spirit.

13. Eugene Tucker is a rather confused philosopher who develops ideas at the intersection of nihilistic materialism and Lovecraftans horrors. Significant works: The horror of philosophy in 3 volumes.

14. Sadie Plant — philosopher, cyberfeminist. Significant works: Zeros and ones.

15. Viveiros de Castro — Brazilian philosophizing anthropologist who discovered the existence of proto-philosophy among the pre-state tribes of South America; author of the concepts of perspectivism and multinaturalism. Significant works: Cannibal metaphysics.

16. Richard Dawkins — British philosophizing biologist, author of the theory of the selfish gene as a biological replicator and the concept of the meme as a self-reproducing unit of cultural information. Significant works: The Selfish Gene, The Blind Watchmaker, God as an Illusion.

17. Gilbert Simondon — French philosopher of technology. Significant works: On the mode of existence of technical objects.

18. Yuk Hui — Chinese philosopher of computer systems. Significant works: On the mode of existence of digital objects, Recursivity and contingency.

19. Yoel Regev is a philosopher who develops the ideas of the materialist dialectics of coincidence. Significant works: Coincidentology, The Impossible and Coincidence, Radical TJinh.

20. Alexander Vetushinsky is a Russian philosopher who develops an alternative classification of the stages of development of materialism: anti-spiritualistic in the 17-19 centuries, anti-idealistic in the 19-20 centuries. and anti-obscurantist in the 20-21st centuries. Significant works: In the name of matter.

Finding a relationship between their ideas and the ideas of Soviet philosophy would at the same time be a response to the remarks of the philosopher and left-wing accelerationist M. Fedorchenko, who rightly notes that often the study of the history of Marxism and leftist thought begins and ends with the study of Soviet philosophers alone outside the world and modern context, which can be characterized as a clear manifestation of dogmatic thinking.

The opposite extreme is the indiscriminate acceptance of all modern ideas, as well as the complete rejection of the achievements of the previous history of philosophy, including philosophical ideas that developed during the Soviet period.

Considering the ideas of Soviet and modern philosophers in conjunction is the only way to avoid both mistakes during the study.

3. About practice

The fourth remark is the question of the significance of the results of consideration of the history of Soviet and modern philosophy for the political practice of transforming the world, to which Marx’s eleventh thesis on Feuerbach and all Marxist philosophy calls us.

It goes without saying that any philosophical and theoretical research has its own value, regardless of its political, economic, psychoanalytic, artistic or other application. In addition, not everything in science is of direct interest for practice: roughly speaking, for one theorem that has direct applied significance, there may be a dozen theorems and lemmas that are important for proving each other, from the totality of which the first theorem can be proven, which has applied value.

The author of the article himself writes about the need for the latter in the preface to the series. However, identifying the need for a solution and finding the solution itself are two different things. If the main categories of dialectical materialism, as well as the method of their application, still remain in a rather uncertain state, then it is reasonable to ask: does the author have a working hypothesis about which set of categories of dialectical materialism, based on the results of consideration, should be recognized as the best possible, and what might its application look like in the field of criticism of bourgeois ideologies, in specific sciences, in political, artistic, analytical and industrial practice?

I have the following working hypothesis: the main categories of dialectical materialism are the categories of assemblage and its aspects, which I write in more detail in the articles “Schizoanalysis. Four Aspects of Assemblage” (ru version) and “Towards a Materialist Categorization” (ru version). And you can read about their application to the theory and criticism of ideologies in the article “Ideology, or about belief in humans, gods and ghosts.” (ru version) The list of various political deviations given in the article “On the Classification of Opportunisms” (ru version) suggests a further and rather obvious concretization in terms of the ontology of assemblages, while every type of opportunism represents one or another impossibilization, that is, blocking greater opportunities due to the erroneous choice of lesser ones. For example, reformism, defined as “a type of right-wing opportunism, conditioned by the weakness of political practice, distinguished in relation to the denial of revolution in the class struggle, reducing political struggle to small changes in capitalism, opposite to Adventurism, can be interpreted as the impossibilization of large, revolutionary changes in society through wasting energy on implementing small, minor changes that do not change the situation as a whole. Similarly, adventurism, the opposite of reformism, is a deviation defined as “a type of left opportunism, caused by the weakness of political practice, distinguished in relation to the denial of transitional demands in the class struggle, reducing the process of struggle to a series of voluntaristic antics with unpredictable consequences and, opposite to Reformism,” can be understood as the impossibility of large, significant changes in society by wasting energy on the implementation of the super task without taking into account the intermediate tasks necessary to solve it.

From here we can see that the Deleuze-Guattarian materialism of assemblages is not a negation, but an affirmation of orthodox Marxist-Leninist philosophy — that is, a negation of the opportunistic tendencies that deny it, according to the well-known dialectical law, which has repeatedly interested all three groups of comrades.

To further dispel their doubts, let us give another example that clearly demonstrates the difference between humanistic ideology and materialistic worldview. In the event of a labor conflict between the workers of a particular enterprise and the capitalist exploiting them, the humanist will interpret both the workers and the capitalist as abstract individuals located in the place of their biological bodies and identical to the latter. Accordingly, an appeal to the capitalist about improving working conditions and wage plans for workers will be expressed by a humanistic theorist into the biological ears growing on the bourgeois’s head, which anyone can be convinced of not only by opening a textbook on human anatomy, but also by looking in the mirror, or by touching their own head. On the contrary, a materialist philosopher, knowing that the capitalist as a social function is different from his biological carrier, can recommend that workers go on strike, stopping production and the capitalist’s profits. Accordingly, the appeal in this case will be made not to the biological ear as an organ that monitors air fluctuations, but to the social ear as an organ that monitors fluctuations in profit. The results of both appeals are obvious: of course, an individual capitalist may accidentally become angry and raise wages out of compassion — but normally this does not happen and will not happen. From here it is clear that citizens who hope to pity the capitalists with the tears of millions of dying, starving, beggars, by listing the victims of exploitation, colonialism and the like will never achieve anything, because they confuse the capitalist as a social relationship with his biological carrier.

The understanding of voice and hearing as complex social objects, distinct from their physiological equivalents, was in principle already laid down in the works of Marx; We can find further clarification of this issue in the works of outstanding psychologists and psychoanalysts of the 20th century: L. S. Vygotsky, J. Lacan, F. Guattari and others. Their theoretical study using data from specific sciences, the categorical apparatus of materialist dialectics, systems theory and assemblage theory is an important research task. An equally important task, which does not cancel the first one, and depends on its solution, is the question of applying these conclusions to the transformation of the surrounding reality and the achievement of communism as a whole.

Thus, correctly understood modern philosophy leads to a clarification and expansion of the understanding of political and other types of practice — but only under the condition of a comprehensive consideration of various theories in comparison with each other and in accordance with the norms of the dialectical method. The solution to the problem of the adequacy and unity of method, theory and practice in the struggle for communism is possible only by the common efforts of the most conscious and active members of society, to whom Marx’s teaching was addressed from the moment of its inception.